Throughout 1918, death loomed over the globe. The immense armies of World War I engaged in brutal battle after brutal battle, political and military leaders marching millions of young men into trenches and tear gas. But while these leaders played pyrrhic war games, their homefronts devolved into killing fields of equal or greater magnitude.

The influenza of 1918 swept across rural and urban areas alike, a dark shroud of death devastating families, overwhelming public officials, and terrorizing everyone. Caskets could not be built fast enough to keep up with the body count. Morticians stopped embalming, and everyday people were forced to dig mass graves to bury the corpses piling up.

To grasp the striking terror of this carnage, we must go straight to the source – the survivors.

Thwip! Thwip! Thwip!

The reedy oak switch sliced through the air, laying sharp stinging blows to Martha Risner’s calves. Julia, her mother, was incensed that she had ruined a new dress by playing around in the mud.

“Now wash up and put yourself to bed!” she ordered.

Martha, months away from turning 5, complied. When she woke the next day, a thick fog had fallen over the mountainous West Virginia coal-mining town where the Risner family lived. As it descended, so too did a deadly and mysterious illness. Overnight, the entire town was sick. Kids, wives, coal-miners, farmers, preachers… It seemed like everyone. Was it the coal? The fog? Nobody had an answer.

Martha’s whole family fell intensely ill. Hacking coughs echoed through the small Risner home, throbbing aches filling their bodies, blood running from their noses. A day passed. Maybe two. No one seemed to get better. Though Jake had recovered quickly, his parents were barely well enough to care for him.

Coming in and out of consciousness as her young body fought to survive, Martha woke one morning to find her father gone. Mom was too weak to get out of bed. Jake cried from the kitchen.

Hours passed.

The afternoon sun slid toward the horizon and cast long shadows within the house. Then without warning, the front door burst open. Her father stumbled into the kitchen, half delirious from his trip. He was followed by a boy – Martha’s 14-year-old uncle, Adis.

“Wait here,” Adam told Adis, who took a seat at the kitchen table and petted his nephew Jake’s head, jaw clenched, staring blankly through a small window near the table. He looked pale and weak.

Adam made his way to the bedroom where Julia slept.

“Jules,” Martha overheard him murmur. “Jules, I’m sorry. They’re gone. John, Amanda, McKinley. They’ve all passed—”

Before he could finish, Julia erupted into wailing, agonized cries. Her mother, father, and 17-year-old brother were dead, three more casualties of a horrific scourge consuming the globe.

Ayer, Massachusetts was a sleepy village in 1917, essentially just a single street with a few businesses and a city hall. But with American entry into World War I in mid-1917, Ayer transformed almost overnight.

Thousands of troops descended on the area, spending 2.5 months turning about 8 square miles of brushy swampland into a military fort – constructing over 10 buildings a day and installing over 2000 showers, 400 miles of electrical wire, and 600 miles of pipe. The newly minted Fort Devens held about 10,000 troops by September of 1917.

Why was Ayer chosen? It happened to be hub of existing major railroads – perfect to ship troops to various encampments before heading to war.

Ida Naparstek, a 5-year-old resident of Ayer in 1918, recalled a chilling scene during the height of the influenza pandemic. On her way downtown, she passed the railroad that had enticed the US military to come to Ayer. The tracks were lined with long, black wooden boxes, four high and three deep. But the boxes weren’t filled with supplies or guns or ammo.

They were caskets – each one carrying the body of a US soldier who had died from the flu before they even reached the battlefield. The military was in the process of loading these caskets into the railcars, shipping them to families across the country to say their final good-bye.

At the age of 24, James Wallace was fresh out of medical school and fresh into the Navy, stationed at a post on the waters of Lake Michigan.

The summer months were beautiful – and busy – as Wallace churned out physicals and blood tests each day to certify battle-readiness for tens of thousands of men drafted into war. He also spent time on the wards, treating everything from training wounds to venereal disease to the occasional “three-day fever” – a moderate flu that kept soldiers bed-ridden for about three days.

But as the weather turned cold in early September, everything changed.

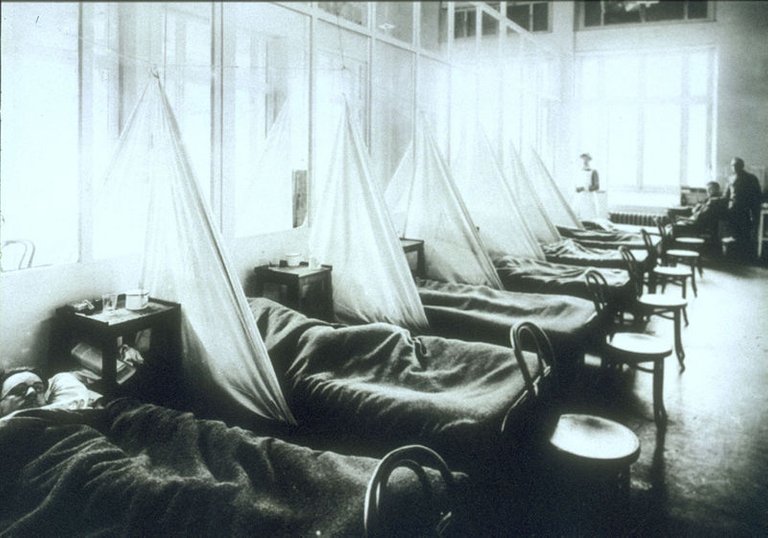

“[The flu] struck the training station like a bomb,” said Wallace of September 13, 1918, the first day he was assigned to a dedicated flu ward. Thousands were sick overnight, filling each of the 3,000 beds on the ward. Wallace recalls young men stricken with “violent broncho-pneumonia.”

Painful cough drudging up thick sputum, blood running from the nose, mouth, and sometimes ears, paired with high fever and heavy body aches. Some men developed red-purple spots on their face and neck, known as “petechiae” – they coughed so hard they burst tiny blood vessels beneath the skin.

The unlucky slowly turned blue, unable to breathe enough air to stay alive, struggling against suffocation by virus.

“The death rate was unbelievable,” wrote Wallace. “Over 100 a day.”

Wallace’s account mirrors other accounts from army doctors across the country. At military bases from Kansas to Chicago to Boston, thousands of healthy young men were falling ill. Even more striking, they were dying by the hundreds, an extremely rare outcome for flu-stricken men in their 20’s and 30’s.

Totally overwhelmed, the medical staff had few options for treatment.

As Wallace recalled:

“Not much but aspirin and, in the hands of some doctors, whiskey.”

Stories of sudden illness and rapid death are characteristic of the 1918 flu. What began as usual influenza would morph into a killer within hours. Ordinary people would begin feeling ill at work and be dead by nightfall.

Battlefield death tolls at the height of one of the world’s most horrific wars paled in comparison to the merciless slaughter caused by the 1918 flu. In fact, the upper estimate of all war-related death (~20,000,000) amounts to less than half the lower estimate of the influenza’s global death toll (~50,000,000).

More troubling and puzzling, men and women in prime physical condition seemed to me the most susceptible to death. The immune system at that age is as robust as it will ever be. How could hundreds of thousands of soldiers not only fall ill, but die within a matter of days? How did it spread so fast across the globe, infecting half the world’s population in a matter of months?

Like most medical professionals at the time, Wallace had no idea the troops he fought to save, like the thousands of soldiers shuttled through Fort Devens in Massachusetts, were helping spread a black hand of death across the globe, squeezing millions of airways shut.

Next week, we’ll look at the role the “war to end all wars” played in turning a lethal virus into a worldwide executioner. Until then.

This is the second part of a series on the 1918 influenza pandemic; Read Episode 1.

The stories in this episode were adapted from the Centers of Disease Control's "Pandemic Influenza Storybook."

Terrifying... Can't imagine what it'd be like to have friends, family, neighbors dying right and left. Thanks for illuminating that horror since our society seems to have almost forgotten it. As I was reading Homo Deus a few months ago, it made it clear to me that we, humans, were for the longest time focused on surviving. Now we are on to seeking eternal life and exploring other planets.

"We learn from history that we learn nothing from history."

George Bernard Shaw

Ok may be a more positive quote

"Those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it."

George Santayana

That post is really interesting.

It's unbelievable what humans can do to other humans. May God comfort them in heaven.

Yes, I heard of this. Worse than the war itself.

Upvoted.

science fiction, fantasy, erotica

check out some posts, no obligation @joe.nobel

Also now following :)

Followed back! @joe.nobel

Yes, it was definitely worse than the war itself. And paradoxically the war was instrumental in making the pandemic so bad, which I'll talk about next week. The story begins in a dusty town smack in the middle of Kansas...

Thanks for the read!

50SP, 100SP, 250SP, 500SP, 1000SP, 5000SP Don't delegate so much that you have less than 50SP left on your account.This post has received a 2.49% upvote from @msp-bidbot thanks to: @warrensz. Delegate SP to this public bot and get paid daily:

10.32% @pushup from @warrensz

Thanks for your good posts, I followed you! +UP