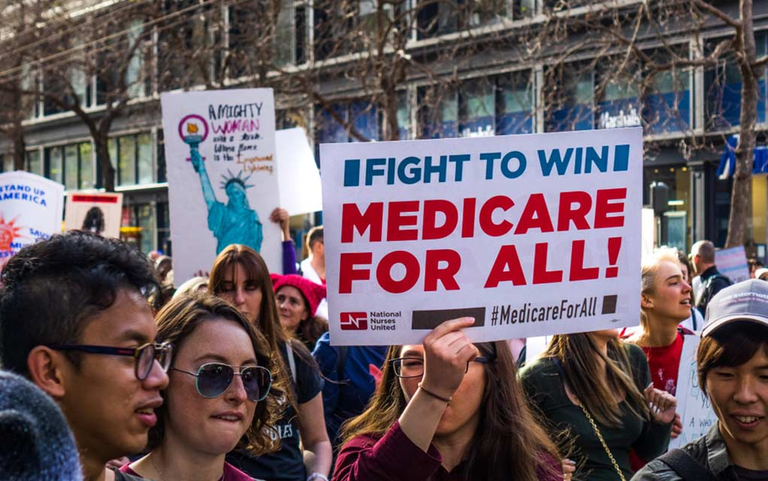

Despite the growing political discourse in America, there is one sentiment that remains the same across almost every demographic: There is something deeply wrong with modern healthcare. All too often, it is impossible to get cost estimates until after the service has been provided, many often feel devalued and improperly cared for once they do receive treatment, and after all of that, there’s probably a 50% chance the insurance company will deny the whole claim anyways, placing the burden of cost squarely on the consumer’s shoulders. The United States sits as one of the most economically developed countries in the world, and yet, its healthcare system ranks beneath practically every other similarly advanced country. As such, the natural step is to look towards what other countries are doing, and this is where the rallying cry of Universal Healthcare comes from.

Universal Healthcare’s Appealing Failures

Universal Healthcare is a system by which healthcare is entirely provided by the government at no cost to the consumer. This is often enabled through substantial taxes on the citizenry, but it provides a safety net to those who need substantial medical procedures that they will not be bankrupted for the costs of living. On the surface, this seems like the perfect solution to the American problem - it is a 100% reduction in price! And yet, it still does not address the subpar service.

Basic supply and demand dictate that, when prices are artificially lowered (or, in this case, extinguished), it creates excess demand. Since prices cannot rise to curb this, the supply must either be expanded through a quality reduction or limited in its roll out. Sure, we may wait now for exorbitant amounts of time while insurance negotiates prices and claims, but universal healthcare would only introduce a new burden, as it cannot reasonably satisfy the demand being placed on it. Furthermore, at least in the United State’s semi-privatized condition, there is some competition that drives innovation. In a socialized system, that competition is completely eliminated due to government control, meaning that there is zero incentive to provide improving services at higher quality, as the government will continue to back the industry no matter what.

The current system may be bad, but it would be no better under a universal plan, so what is the real solution? What Dr. Sean Flynn proposes may at first seem to be the very opposite of what changes the system needs, but through verifiable evidence, it seems clear that the answer is not socialism, but capitalism.

More, Not Less, Capitalism

More capitalism? Really? When I first heard this notion, my mind immediately jumped to the insurance companies that are all too quick to deny your claim if it means they don’t have to pay it and increase their own profit margins; however, by increasing capitalism in healthcare, it is not the insurance companies that would benefit, but the consumers.

Dr. Flynn illustrates this best by taking a deep look into Singapore’s healthcare system, which operates on three principles, the first of which is forced saving for healthcare expenses by the government through taxation, deemed MediSave. Similarly to the United State’s social security program, this requires a portion of each worker’s paycheck to go into savings to be used should they have a medical emergency later. The second of these tenets is MediShield, which provides basic insurance whose premiums can be paid out of each individual’s MediSave accounts. The final pillar is MediFund, which allows those undergoing extreme procedures who would otherwise deplete their MediSave account and be unable to pay their MediShield to apply for the government to pay for the procedure, which is approved in roughly 99.7% of cases, according to Dr. Flynn. In nearly all cases, there is no middle-man insurance operator, the payment almost always comes straight from the citizen. Finally, the incentive to provide quality services at low prices returns, as the customers are no longer bound by where their insurance will allow them to go, but rather, where they can find the best deal. This encourages healthcare providers to lower their prices while improving services all at the direct benefit of the customer, making Singapore rank as one of the healthiest nations in the world.

So, how could the United States reasonably implement this? As Dr. Flynn points out, taking Singapore’s exact system would be nearly impossible due to the general disfavor most Americans cast on raised taxes; however, there is an easy solution, one already being displayed by Whole Foods that has clear benefits. Rather than the usual simple health insurance, Whole Foods provides its workers with $1800 annually for health costs, and any money not spent may be kept by the employee; however, should they need more, they are still insured. Now, there is an incentive for people to save that money as it can stay within their own pockets, and health costs by these employees actually decreased by 35%, saving both the employees money and Whole Foods as well, for not nearly as many insurance claims were filed. This may seem like a small benefit, but if this were enacted across many companies so that everyone decreased health care spending by 35%, not just this small subset of workers, hospitals would be forced to lower prices, allowing for a system such as Singapore’s where the desire to please is given not to the insurance companies, but the consumers.

Capitalism is not healthcare’s enemy, but its friend. Only through placing purchasing power back in the hands of the individual and out of insurance (God forbid the government ever find it) can consumers once again be prioritized, ensuring high quality for affordable prices. I, too, may have been skeptical at first regarding such a system, but the net-positive it creates across society for all demographics is indisputable, as it returns the power to the people.