The Hebrew language has evolved over time. Even during the course of writing the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament), Biblical Hebrew changed, which is apparent when you compare early Biblical texts with late ones.

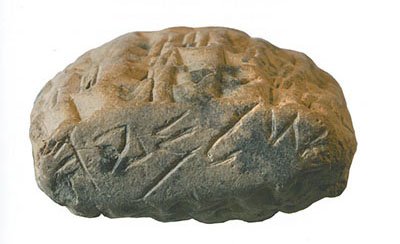

Holding on to Biblical Hebrew: Even during the Babylonian Exile, Jewish exiles continued to use the Hebrew language. This promissory note from Al-Yahudu, also known as Judahtown, in Babylonia is inscribed with a Yahwistic name, Shelemyah, which is written in paleo-Hebrew script.Photo: Cindy and David Sofer Collection, Al-Yahudu No. 010

How was the Bible written during and after the Babylonian Exile? Did the Biblical authors continue to use the Hebrew language even though they were living in lands where Hebrew was no longer the common language? In his article “How Hebrew Became a Holy Language,” published in the January/February 2017 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review, Jan Joosten explains that Biblical Hebrew did not go out of use. Rather the Jewish population continued to use it—and even attached a new reverence to it.

After Nebuchadnezzar sacked Jerusalem and deported Judahite captives to Babylonia, he settled them in cities and villages, such as Al-Yahudu (also known as Judahtown), around the River Chebar. The official language of the Babylonian Empire was Aramaic. Although the Jewish deportees communicated in Aramaic with their new neighbors, they continued to write and speak the Hebrew language in their communities, which helped them preserve a distinct identity. An archive from Al-Yahudu demonstrates this. For example, a promissory note from Al-Yahudu (see above) is inscribed with the Hebrew name Shelemyah, which contains the element “yah” that connects the name holder to his deity, Yahweh. The note is written in paleo-Hebrew script, not Aramaic cuneiform.