After reading this post on Nazi tanks and Blitzkriegtechnological element of Blitzkrieg. It was only with relatively compact, portable radios that it became possible to coordinate combined arms attacks as the Nazis did early in the Second World War, and as other major military powers have done since then. If tracked, armored vehicles and ground attack aircraft were not new in 1939, their close coordination was, and it made possible the second truly defining feature of blitzkrieg: speed. With ground attack aircraft acting as a kind of "flying artillery," German armored forces could call upon air support against enemy forces much more quickly than ever before. And this in turn leads to the third crucial element: penetration. Military commanders have long understood the importance of concentrating force at an enemy's weak points; Napoleon, with his background in artillery, was a master of this. Blitzkrieg tactics called for the concentration of more force than had ever been seen at that point, in which armored spearheads, supported by aircraft, could reliably punch holes in enemy defenses. With the speed of tanks and the ability of aircraft to continue offering support, these armored spearheads could penetrate deep into their enemy's rear, cutting supply lines, isolating slower-moving bodies of enemy infantry, and capturing enemy supply dumps and command centers. After the slow, positional warfare of 1914 to 1918, then, Blitzkrieg made warfare mobile again., by @liberosist (which you should check out), I was struck by his definition of "Blitzkrieg," and wanted to clarify my own thinking on the subject. Nazi Germany's campaigns against Poland in 1939, the Low Countries and France in 1940, and the Soviet Union are justifiably famous for their use of armor and ground attack aircraft, as well as for their decisive nature. But, neither tanks nor aircraft were exactly new in the late 1930s and early 1940s; both, after all, had played prominent roles in the First World War. And, plenty of campaigns and wars in the past had been settled in a decisive manner. So what was different about how the Nazis used those tools to defeat Poland, France, and the Low Countries, and to push the Soviet Army all the to Moscow? I surveyed a few major texts on the subject, and taken together, several crucial features emerge: radio, speed, and penetration. First, it is clear that radio was the defining

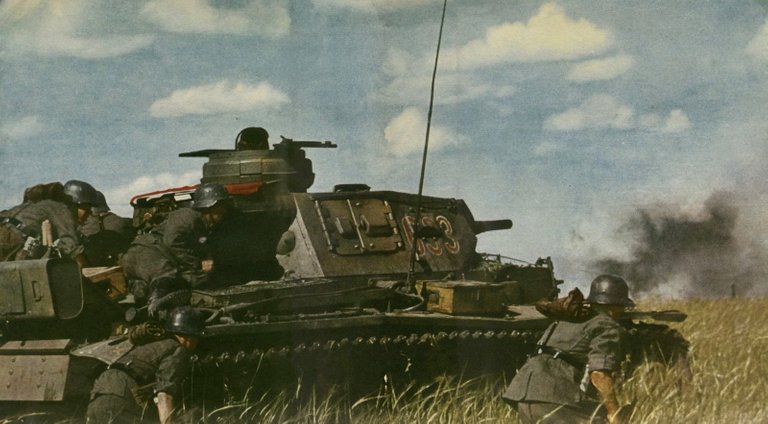

Note the flag facing up on the back of this tank--a necessary identifier when coordinating with flying artillery. Note also the antenna on the right side of the vehicle.

B. H. Liddell Hart is perhaps most famous for his writings on strategy (here), and for his work shortly after 1945 in interviewing German generals (here, and here). Born in 1895, he was a student at Cambridge in 1914, and joined the British Army and rose to the rank of Captain during that conflict. By the mid-1920s, he devoted most of his energies to writing, and was a military correspondent in British newspapers and military editor of the Encyclopedia Britannica (who knew they even had those??). During the 1930s and 1940s, he served in various advisory roles for the British Government and British Army. While his work is now dated, he is never the less a major figure in 20th century military history. In his two-volume History of the Second World War, he offers a fairly limited definition of "Blitzkrieg." He opens his chapter on the "Overrunning of Poland" by noting that "The campaign in Poland was the first demonstration, and proof, in war of the theory of mobile warfare by armored and air forces in combination" (I:27). Liddell Hart noted that the earliest such theories, of high-speed, tank-centered warfare, had been developed in Britain in the 1920s. However, due to a lack of funding in the Great Depression, and perhaps a lack of imagination by both political and military leaders, these theories were not followed up. Indeed, Winston Churchill himself, who played an important role in sponsoring the tank in World War I and who was Chancellor of the Exchequer until 1929, remarked after the Second World War that he "did not comprehend the violence of the revolution effected since the last war by the incursion of a mass of fast-moving heavy armor. I knew about it, but it had not altered my inward convictions as it should have done" (I:19-20). Churchill, in other words, did not see Blitzkrieg coming any more than anyone else outside the most optimistic members of the German high command.

John Keegan, another major figure in 20th-century military history and most famous for his social history of war The Face of Battle, provided a more technologically detailed definition and description of Blitzkrieg. In his A History of Warfare, he argued that Blitzkrieg, "a journalists' term term but a descriptive one, ... concentrated the tanks of the panzer divisions into an offensive phalanx, supported by squadrons of dive-bombers as 'flying artillery,' which, when driven against a defended line at a weak spot - any spot was, by definition, weak when struck by such a preponderant force - cracked it and then swept on to spread confusion in its wake" (369). While he likened Blitzkrieg to historical examples of the concentration of heavy cavalry--citing Leuctra, Gaugamela, and Marengo, among others--he noted that Blitzkrieg added the ability of rapid exploitation to the penetrating abilities of massed armor. Previous armies were limited by the horse- and human flesh needed to move; the Wehrmacht in 1939 could travel at the speed of its engines. Ultimately, however, the key technological innovation was the radio. During the First World War, radios were too large and unreliable for mobile warfare, effective only aboard ships. Miniaturization made them far more portable by the 1930s, and thus German tanks and aircraft could stay in constant communication with radios inside their vehicles. Keegan explained that mobile radio "was the basis for an offensive revolution. Its nature was encapsulated in remarks by Edward Milch [Milk!], at a pre-war conference on Blitzkrieg tactics: 'The dive bombers will form a flying artillery, directed to work with ground forces through good radio communications. ... tanks and planes will be [at the commander's disposition]. The real secret is speed - speed of attack through speed of communication" (370).

Note the images of a wonderful collection of German WWII radios here: http://www.la6nca.net/tysk/10wsc/index.htm See especially the LA6NCA, the "standard transmitter used in all German panzer vehicles from 1939 to 1945."

Finally, in The Oxford Illustrated History of Modern War (Charles Townsend, ed.), a chapter by Martin van Creveld considers "Technology and War." He links the theoretical developments that Liddell Hart discussed with the tactical discussion offered by Keegan, explaining that while war ended in 1918, attempts to develop tactics that would maximize the capabilities of tanks and aircraft continued. "The first to hit on an answer," he argues, "not just on paper [referring to the British, but they would say they demonstrated it on Salisbury Plain in 1927!] but in the form of a functioning organization, were the Germans who, having been defeated, were more open-minded than the victors. By the second half of the 1930s they were using another technical instrument, radio, to tie tanks and aircraft into an integrated team" (191). This, then, enabled the combined arms approach of Blitzkrieg: rapid, radio-coordinated attacks of armored spearheads and "flying artillery," which could rapidly penetrate enemy lines and drive deep behind them, bringing mobility back to the battlefield after its comparative absence on the Western Front from 1914 to 1918.

This post ended up being longer than I intended, so I hope you've read this far. If so, I'll take this opportunity to introduce myself: I'm a professional historian and a native and lifelong resident of Los Angeles. I earned my PhD last year, and while my real specialization in 19th-century Britain, I teach a LOT of different courses, so I dip my toes into all kinds of history. Steemit seems like a fascinating community, and I hope I can find a place here.

Also, I hope I've done links and images correctly--please let me know if I should do it differently.

Sources:

B. H. Liddell Hart. History of the Second World War. New York: Capricorn Books, 1971.

John Keegan. A History of Warfare. New York: Vintage Books, 1993.

Charles Townsend, ed. The Oxford Illustrated History of Modern Warfare. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Outstanding analysis of a little-understood technological part of the blitzkrieg. Truly, without the radio, this maneuver could not have been successfully executed. I never thought of that before. Well done.

Welcome to Steem @agentdcf I have sent you a tip

Congratulations @agentdcf! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honnor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPBy upvoting this notification, you can help all Steemit users. Learn how here!