At Vergelegen Willem Adriaan van der Stel had well over 200 slaves- possibly 300- the most ever in private hands and on the property in the cape. He had built up his enormous slaveholding from slavery expeditions, passing ships and on the local market. Large slaveholdings such as this where the exception in the Cape: it was only the Dutch East India Company slave lodge in the Cape Town that exceeded Vergelegen in size.

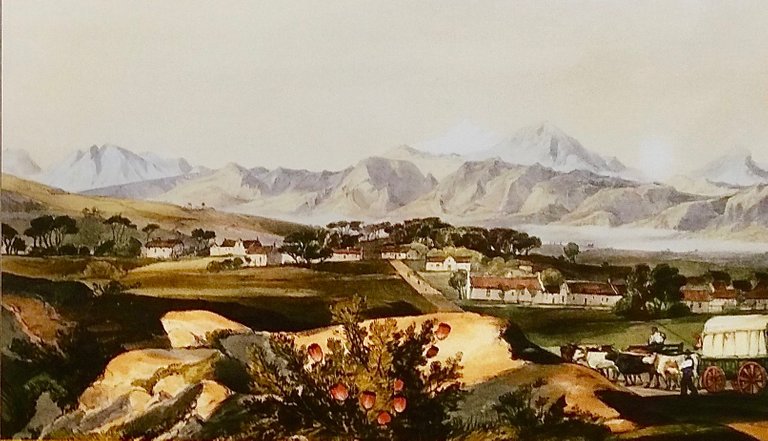

Part 1 Slavery in South Africa / Willem Adriaan van der Stel and his Old Cape Farmstead

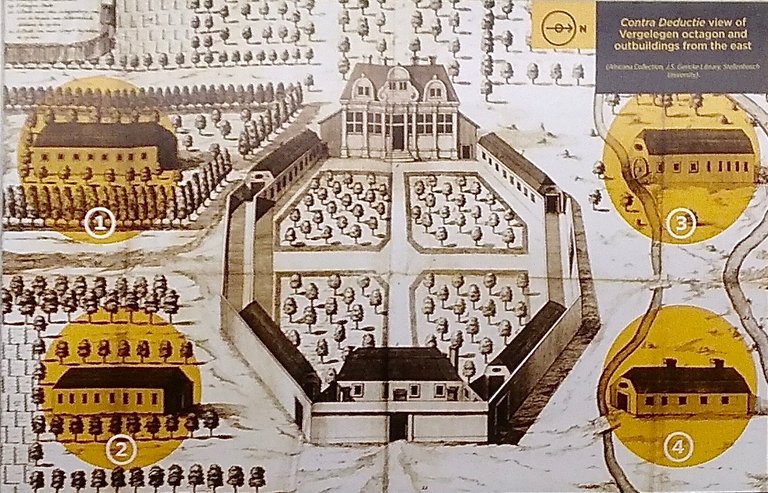

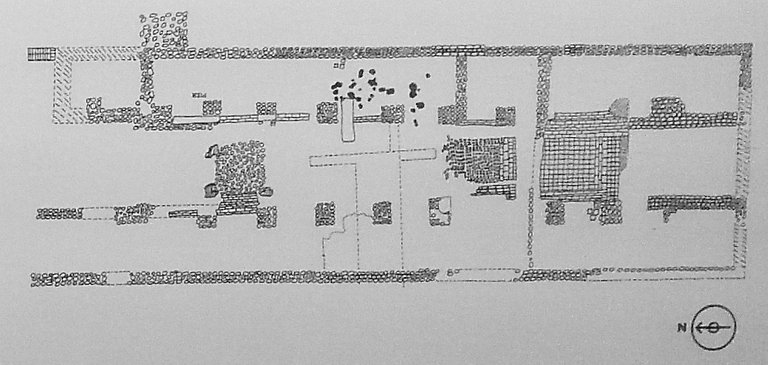

The archaeologists uncovered three of the four outbuildings surrounding the octagonal enclosure, namely slave lodge, water mill and wine cellar. They also discovered that remodelling occurred in the latter half of the 18th century before the buildings were eventually demolished. The focus of the project was to investigate the institution of slavery in its colonial context so these findings were of particular significance.

After much deliberation, it was decided to cover up the archaeological excavations in order to better preserve them. Anglo American continued to pursue ways of bringing the information to public attention by means of the displays and model of the slave lodge.

1 Wine cellar, 2 Pletjieshok, 3 Mill and stables, 4 Slave Lodge

No record of the living arrangements in Vergelegen’s slave lodge exists. What the partitioned areas in the foundations were used for can only be conjectured. Apart from slaves, the lodge would have accommodated other farm workers, including knechts (European labourers). Little more than a tenth of the slaves were women; although they were kept away from the men, children were born into bondage and had to be cared for. Despite the size of the slave lodge, it would have been difficult to sleep 200 people without using space in the loft.

The company’s slave lodge was quadrangular and stood between the church and the company’s garden. Built in 1679 it was the third company slave lodge in the Cape. This forbidding two storey building was windowless and dark and could house up to 1000 slaves. The company would replenish its slave holdings by sending slaving expeditions to Madagascar during the course of the 18th century. The building is now the Iziko slave lodge museum.

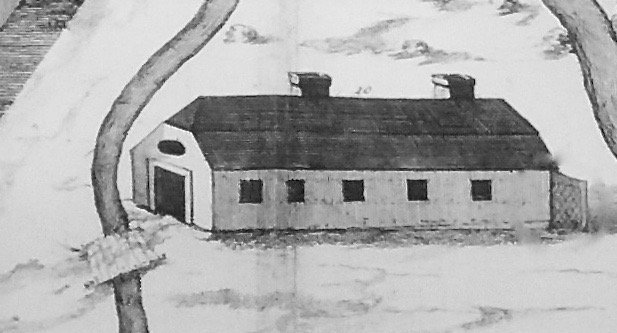

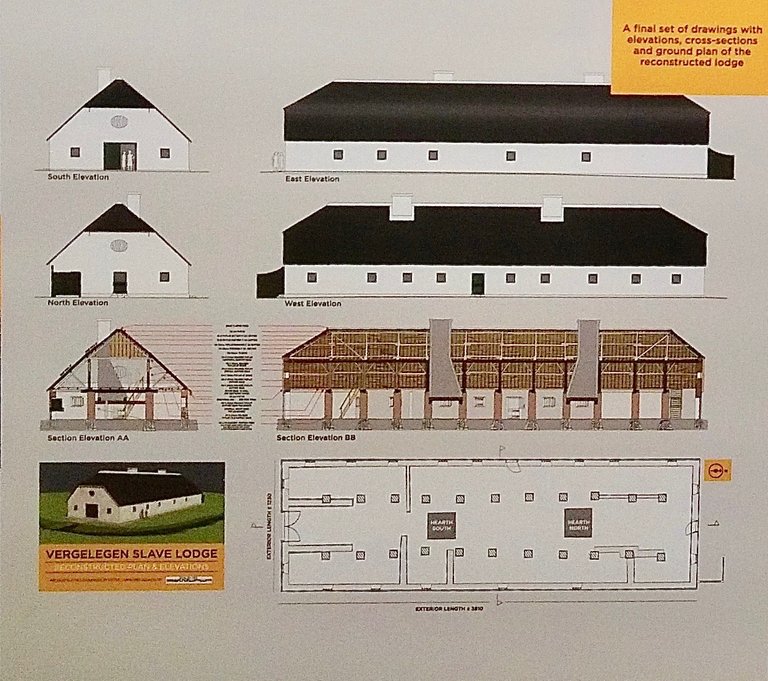

The slave lodge measured 122 x 38 Cape feet (38,4 x 12.0 m). It had 11 pairs of piers with matching crossbeams supporting the roof. There was a central aisle in which two hearts paved in clay were situated. Built to house hundreds of van der Stel’s slaves, the lodge would have become half empty as fewer slaves were retained. It was demolished before slavery came to an end in the Cape in 1838.

Willem Adriaan justified keeping his best slaves in his home because of the filth and stench of the lodge. This gives some idea of how of a crowded and lacking in sanitation it was. Yet conditions at Vergelegen must have been better than elsewhere. Willem Adriaan was accused of harbouring slaves that had escaped from neighbouring farms. William Adriaan provided schooling for children at the slave lodge and baptized at least 12, which meant they could not be sold again. He also manumitted (freed) others.

Because of the significance of the Vergelegen slave lodge in 2004 Anglo American commissioned Peter Laponder to make a model of it. The model was to be based on the archaeological findings of the 1990s and represent the Willem Adriaan van der Stel period of 1700-1708.

Although foundations were uncovered during excavations in the structure of the slave lodge above-ground was left to conjecture. For the model maker, this meant marrying contemporary images to the building with architectural drawings of *hallehuisen* in the Netherlands. Consulting local experts on vernacular architecture and visiting historic sites.

Having put various concepts to the test the model maker proceeded to reconstruct lodge. In the finishing touches, he attempt to give the feeling of research-based authenticity. The lodge had to appear lived in, with grimy walls to accentuate the slave's squalid conditions. Floors were of uneven clay and soot from the open hearths penetrated everywhere.

Illustrations in the korte deductie and contra deductie provided valuable architectural details and different perspectives of the slave lodge at Vergelegen. As the publications were clearly biased, several discrepancies came to the fore. Of the two, the contra deductie is considered to be the more reliable version, yet it contains some puzzling features.

The unusual width of the large roof was problematic. On closer inspection of the contra deductie most of the Vergelegen buildings appear to have hipped Mansard roofs. This allowed for a wide roof span in a requisite 45° pitch for thatch, and the roof was reconstructed accordingly.

The key issue was the construction material of the lodge. In Europe, the hallehuisen were mainly constructed of wood, but in the Cape - with its shortage of wood – stone, bricks and mortar would have been used instead. Solid stone piers in the foundations of the slave lodge point towards the use of masonry pillars to support the roof.

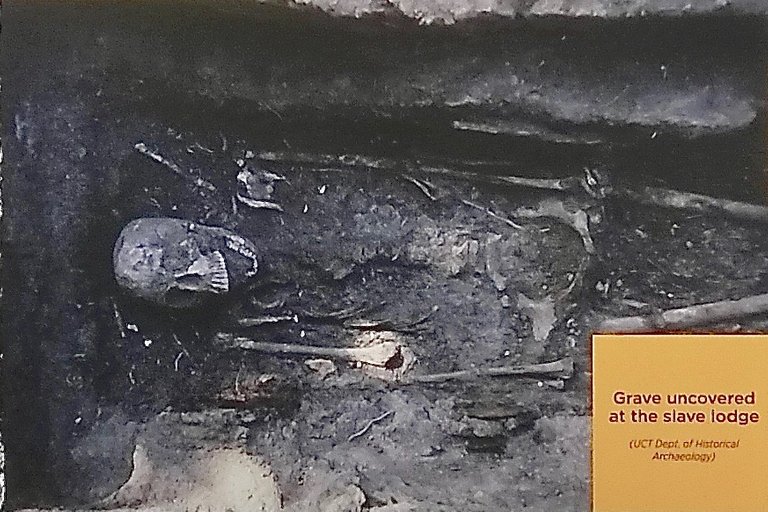

A grave of a slave woman from the late 18th century was discovered in the floor of the slave lodge. She seems to have held a special status and this was the only grave to be found. Scientists were able to establish that the skeleton was that of a woman in her 50s who sat for long periods on her haunches probably cooking at low fires. Isotopic testing of her bones revealed a change of diet from tropical grains as a child to wheat, rice and fish as an adult. This was consistent with the movement of slaves from the tropics to the temperate climate of the Cape.

For members of staff who had lived in the area for generations the slave woman, affectionately known as “Flora” offered a tangible link with the past. They were consulted before her remains were removed and took part in a small ceremony to rebury her after the scientific tests were performed.

The excavations at Vergelegen coincided with growing interest of the Cape slave history. Inspired by the works of eminent historians, communities began to trace their family connections to slaves. Ebrahim Rhoda, who wrote the story about the Muslims in the Strand told the story of Eva a slave girl born at in 1811. At the age of 15, Eva was sold to the Morkels at Onverwatcht. There she met another slave Abraham and had three children by him. With the emancipation, they were able to marry and move to the Wesley Mission Station in Somerset West to make a new start. They adopted the surname Rhoda and have Christian and Muslim descendants in the area.

Origins of the slaves the names of Willem Adriaans van der Stel’s slaves are memorialized on the ceiling of the slave lodge. Although they were also given westernized names when they were sold, slaves continued to be known by their land of origin. Most slaves came from the East Indies and their diverse cultures languages and religions made the cape one of the most cosmopolitan slave societies in the world.

References

Photos: @highonthehog

Images: sources linked below

Schoeman Karl, Early slavery at the Cape of Good Hope, 1652-1717. Pretoria: Protea Book House, 2007

Reader’s Digest, The Illustrated History of South Africa: The Real Story. Cape Town, SA: Reader’s Digest Association, 1988

Armstrong, James, ‘The Slaves, 1652-1795’, in Richard Elphick and Hermann Gilliomee, The Shaping of South African Society, 1652-1820. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman, 1986

Markell, Ann B., Building on the Past: The Architecture and Archaeology of Vergelegen. South African Archaeological Society, Goodwin Series 7:71–83, 1993

De Bosdari, C., Cape Dutch Houses and Farms. A. A. Balkema, Cape Town, South Africa, 1953

Tas Adam, and Nicolaas van der Heyden 1712 Contra Deductie. Nicolas ten Hoorn, Amsterdam.