Precursor to the Mỹ Lai Massacre: 1968 Phong Nhị, Phong Nhất_19: A photograph from the Da Nang Museum

The first time I saw the photograph at the Da Nang Museum, located on Trầ Phún street in the city of Da Nang, was in February of 2017.

It was on the second floor in the Vietnam War Crime corner, among a long cylindrical carousel of photographs. There were 9 people in the photograph. An old man with a long white beard, an old lady with a towel on her head, middle-aged men, young men, and even boys. They were standing against a backdrop of dense trees that almost appeared to be a mountain. Without reading the description provided, it was difficult to tell what is going on. This is what it said in Vietnamese and in English:

“Survivors in Massacre of 127 civilians by U.S and South Korean soldiers at Phong Nhi, Dien Ban, Quang Nam, in January (based on the lunar calendar; February based on the solar calendar) 1968.” I was taken by surprise. Aside of the fact that US troops were wrongly accused of being involved and the number of victims was inaccurate, I couldn’t believe that this was Phong Nhị.

The photograph of the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất massacre survivors, displayed on the second floor at the Da Nang Museum. This is a rare photograph wherein many of the survivors are gathered together in one place.

From May of 2000 to January of 2019, I visited Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất a total of 10 times, meeting with survivors and trying to get a hold of photographs from the 60s and 70s from the villagers. All there was was one family photograph that the US troops took for residential administrative purposes, and the rest were identification photographs. The photograph at the Da Nang museum was the first in which all the survivors appeared together in one place.

I looked intently at the faces in the photograph. There was nobody that I could recognize. The village was obliterated that day, so I assumed that in order to be able to gather the survivors in one place like this, the photograph must have been taken after 1975. I was curious as to whether these were actual Phong Nhị residents. What were their names? Who took this photograph and for what purpose? Even when I solicited a museum employee, I could not obtain any more information. All I was told was that the photograph has been displayed since 2011. I had to take the photograph to Phong Nhị to find out for myself. That was the only way.

“To the far left is Trịnh Thị Thiệt. Next to her is Khuông. Hmmm, I have no idea who the children in the front row are.”(Nguyễn Thanh Cơ, born 1957, Phong Nhị resident)

“That’s Nguyễn Đức Sang on the far right. The fourth one from the left is Đức Sang’s relative, I think. As for the rest of these people... who are they?” (Trầ Diệp, born 1953, Phong Nhất resident)

“The third person from the left is my maternal grandmother, Nguyễn Thị Soạn. The person on the far left is indeed, my older brother Đức Sang. To his right is Nguyễn Phán, and next to Nguyễn Phán is Nguyễn Bưởi. To the far left in the front row is Lê Đình Mận, and I think the one to his right is the son of Phan Mậu... what was his name again? Anyway, now we only have one more person left to identify. Back row, center. Oh, right! He’s my distant relative. Năm Trưởng.” (Nguyễn Thị Thanh, born 1960, Phong Nhị resident).

Well that was relatively simple. I visited Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất on February 25, 2018. I was able to identify the people in the the photograph by asking three of the survivors I had gotten to know over the years. Of the nine people, four of the elderly men in the back tow had already passed away. They weren’t certain of Năm Trưởng’s whereabouts or whether he was even alive, but the remaining four were still alive. Two of them resided in Phong Nhị, and the other two in Ho Chi Minh. In fact, I had interviewed two of them in the past. It only dawned on me after I was told their names. I decided to look for the younger boys in the photograph, starting with Lê Đình Mận, who lived in Phong Nhị.

Lê Đình Mận, who survived in his mother’s bosom when he was less than one year old. He is in the far left of the front row in the photograph he is holding. Photograph by Humank

Lê Đình Mận’s mother, Hà Thị Diên, photographed by a US soldier who entered Phong Nhị for relief work after the Korean troops had left.

“Yes, the little kid to the left is me. The second person from the far left in the back row is my grandmother, Đoàn Thị Khuông. She passed away in 1988.” This wasn’t my first time meeting Lê Đình Mận. In fact, this was our 5th time seeing each other. He was the youngest survivor, being only about 100 days old at the time of the massacre. He survived while being breastfed by his mother. She was shot by a Korean marine, but she kept her infant shielded, even in her final moments. In a photograph taken by a US soldier, his mother, Hà Thị Diên (34 years old at the time) is lying on the ground with her breasts exposed.

“I only vaguely remember a white person holding his camera. All I know for certain is that he was not Vietnamese.” He said he thinks the photograph was taken where the present-day Điện An People’s Assembly is. “This place actually used to be a shrine. I think it must’ve been immediately after liberation.” Lê Đình Mận was born in 1967, so if the photograph had been taken in 1975, he would’ve been 8 years old. Based on his size in the photograph, it seemed to be about right. “Next to me is my friend, Phan Văn Hạnh. We’re the same age. His family called him Lạng. He lives in Ho Chi Minh now. We grab a drink together when he’s back in town.

Lạng’s family still lives in Phong Nhị. That day I visited his older brother, Phan Văn Thành(born 1954). Phan Văn Thành said he raised his brother because their mother died on the day of the incident, but because they were extremely poor, Lạng was sent to live with his father’s friend in Ho Chi Minh when Lạng turned 13. Lạng didn’t attend school, and instead learned how to fix motorcycles. He used to run a repair shop, but now he works as a motorcycle cab driver. Their father, Phan Mậu, who resorted to sending his younger son to live with his friend, looked on in silence as his older son was being interviewed. He was born in 1928 and had difficulty moving about on his own.

Lạng in Ho Chi Minh. He is the little boy in the front row, right in the 1975 photograph he is holding. Photograph taken by Kwon Hyun-woo.

Lạng’s mother, Nguyễn Thị Liễu, who died in a grenade explosion while hovering over her infant child. Photograph taken by Humank

Lạng, like Lê Đình Mận, was an infant survivor. He too survived because he was suckling at his mother’s breast. The two had their differences too. Lạng’s mother, Nguyễn Thị Liễu (40 years old at the time) died from a grenade explosion, not from being shot. His older sisters, Phan Thị Hồng (8 years old at the time) and Phan Thị Đào(6 years old at the time), who were also hiding together in the shelter, lost their lives as well. Phan Văn Thành said that Lạng survived without a scratch because their mother was hovering over him.

I still cannot forget the first time I heard Lê Đình Mận’s story in 2013. I was astonished by the fate of the infant, as it sounded like something that could only be seen in a movie. Thereafter though, after speaking to many different survivors, I learned that infant survival in massacres was quite common. Just within the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất incident, there were three cases, including the case of Thái Thời, apart from those of Lê Đình Mận and Lạng (Xã Điện Phước, La Hòa village, born 1966).

Even in other regions, there were countless accounts of infants surviving next to their dead mothers. I’ve also heard many witnesses say they saw infants climbing on their mothers’ corpses, trying to suckle on their breasts. As such, massacres kill people, taking no heed to their given circumstance. Yet a mother’s instinct to protect her child prevails, even in the face of such tragedy.

I finally got to meet Lạng on May 12, 2018. He came on his motorcycle to a coffee shop in Huỳnh Tấn Phát, 7th district. “It was when I was in the third grade. I recall it being October.” Lạng’s birthday is February 20, 1967, so it was in fact in 1975. “I was in class when my teacher summoned me to come outside. I met four Vietnamese people and two foreigners, and took pictures with them. They told me it was because I was a survivor of the massacre.”

Lạng had a more vivid memory than Lê Đình Mận. He said it was because he discussed the incident with his father as a child. “I think the man taking the photographs was Asian. I remember thinking he’s probably Filipino. A few years later, we went on a school field trip to the museum, and I remember seeing this very picture with my classmates.” The backdrop appears to be a mountain, but it’s actually a village. Lê Đình Mận said it was where the People’s Assembly was, but Lạng said he thinks it’s a different part of the village. According to the official records of the Điện Bàn Culture and Communications office, 74 people were killed on February 12, 1968 in Phong Nhị, Phong Nhất and even further west in Phong Lục. All the thatch-roofed houses burned down, so there were no houses left. By the time the war ended and the inhabitants began returning one by one, there was a dense growth of trees and shrubs. They were designated land by the government and began rebuilding the village.

The one on the far right in the photograph is Nguyễn Đức Sang. If it is 1975, it would be when he was only 22 years old. He had the most severe injury. He was shot along with his younger sister, Nguyễn Thị Thanh, and was left with scars so big on his stomach and buttocks that he was unable to defecate. It would come out through his belly button. Unlike his sister who was hospitalized for one year, he was in the hospital for seven years before he came back to Phong Nhị in April of 1975. When I interviewed him in 2013 and in 2017, he said he was operated on a total of 11 times, at the hospital in Da Nang, the German hospital ship, a hospital in Tuy Hòa, the US hospital ship No. 17, and a hospital in Ho Chi Minh.

Nguyễn Đức Sang in Ho Chi Minh. He is the young man standing on the far left in the photograph he is holding. He had the most severe injury from the incident, being held in hospitals for seven years thereafter. Photograph taken by Kwon Hyun-woo

On April 17, 2018, I met Nguyen Đức Sang at his home located in the 12th district, the northwest region of outside of Ho Chi Minh. His memory was getting fuzzier. At first, he said the picture might have been taken in 1969. His sister Nguyễn Thị Thanh, came by and corrected his memory, which made him feel uneasy. 1969 was when he was still hospitalized. There was no way Lạng and Lê Đình Mận who were born in 1967 could have been as big as they are in the photographs. Đức Sang changed his mind, agreeing with his sister that it was probably taken in 1975. He couldn’t recall much about the photographer either, however. He seemed to have been badly affected by the incident.

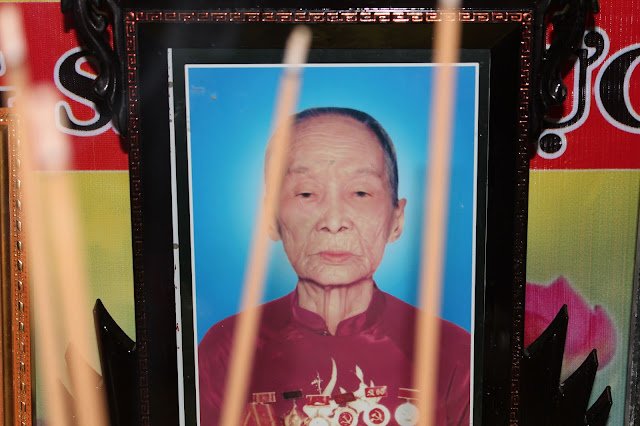

Now all we have remaining is the last survivor from the photograph, Trịnh Thị Thiệt (54 years old in 1975), standing on the far left. Lê Đình Mận was the youngest survivor, Nguyễn Đức Sang had the most severe wounds, and Trịnh Thị Thiệt was the oldest survivor, as she was born in 1921. She was 97 years old when I visited her home on February 25, 2018.

Trịnh Thị Thiệt never married or had children, so she has no family of her own. Instead, she lives with her grand-nephew, Trịnh Cáp(born 1963) and his family, making them a household of 5 generations. Trịnh Thị Thiệt slowly made her way out to the living room, leaning on her cane for support. Her great grandchildren propped her up, but she didn’t appear weak. She merely nodded looking at the printout of the old photograph I brought along.

When I told her I am from Korea, she asked where that is. I was wondering if she was suffering from dementia, but when I said, “Đại Hàn,” she immediately responded, saying, “Đại Hàn were usually short, I never saw one as a tall as you.”

The oldest survivor, 97 year-old Trịnh Thị Thiệt, in February of 2018. She took a photograph with the family of her grand-nephew. When I visited again in January of 2019, she had already passed away. Photograph taken by Humank

It was a matter of seconds. Trịnh Thị Thiệt was planning on going grocery shopping with her village friends, Phan Thị Trí(34 years old at the time and the mother of Nguyễn Thị Thanh) and Vĩnh Điện in the morning of February 12, 1968. It was one day before the first full moon of the lunar new year. She narrowly escaped the fate of her friends because she was late. Nevertheless, she witnessed all of it. The massacre, the rape and the arson, as well as the corpses that were thrown into wells. She also told of how the villagers laid out the corpses in the streets in protest to the incident. She was eloquent and stated her opinion clearly. Her final words left the greatest impression on me.

“It’s been over thirty years (50 in fact) since the incident, yet the Korean government did not ask about our wellbeing or send their greetings.” Such actions indicated an apology.

Should the South Korean government apologize to Vietnam regarding the massacre? Even among those who critically reflect back on Korea’s history of dispatching troops to Vietnam, there are quite a number of people who are skeptical about the need for an official apology from the government. There is also a line of logic that believes that the Vietnamese government, because of the internal political pressures it would cause, actually does not want an apology. Yet the words of this elderly woman, close to a hundred years old, put things into perspective. She made it clear that apart from the realm of interstate relations, an apology needs to be issued, from an ethical standpoint, at least to the victims. She also sharply criticized the Vietnamese government for only looking after the families of those who made an honorable contribution to the state.

On January 2, 2019, I returned to Phong Nhị for the first time in a year. I attempted to meet Trịnh Thị Thiệt one more time at her home, but she wasn’t there. Somebody else in the photograph came to visit me. I was told that she passed away on December 7, 2018; exactly 26 days ago. Her grandnephew told me that she didn’t seem particularly ill the day before and was found the next morning appearing as if she were peacefully asleep. Trịnh Thị Thiệt’s opinion regarding the South Korean government was in essence her will, her parting words. I was suddenly reminded of the former Japanese comfort woman, Kim Bok-Dong, who passed away suddenly, leaving many people feeling unsettled.

A single photograph brought me all the way here. I identified all nine of the people in the picture. I met four in person, one of whom passed away in the last year. I still haven’t figured out who took the photograph, however. Perhaps it was the group of visitors from the old Soviet Union, who went to Sơn Mỹ(Mỹ Lai) where the US troops incited a massacre. There was one employee from the Da Nang museum who could serve as a key to this lock, but he suddenly passed away last year, being only in his 50s. I couldn’t afford to further trace down the origin of the photograph.

The Da Nang Museum in Trầ Phún street, Da Nang. The photograph of the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất survivors is at the very bottom, among the various war crimes photograph displayed in the corner of the second floor of the museum. Photograph taken by Humank

On the same day, I went to the 2nd floor exhibition hall of the Da Nang Museum. Oddly enough, the greatest number of visitors to the Danang Museum is from Korea. It seems that the number of Korean tourists surged after the opening of direct flights to Da Nang from Korea in 2010. Da Nang Museum director, Huin Nh Đình Quốc Thiên (43) said, "Of the 270,000 annual visitors, 45% are Korean." At the exhibition site, there is a large photograph showing Korean troops landing at the Da Nang harbor, and a small picture of soldiers with a resort as their background.

Korean army ranks, nameplates, and epaulets are also on display. Veterans are likely to become very nostalgic. If you ever have the opportunity to visit the Danang museum, I recommend you take a look at the picture of the survivors of Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất. It is not a pleasant photograph. Hidden within is an uncomfortable piece of truth. If you think about the value of that truth and feel the emotions of the survivors in the photograph, your travel to Da Nang may leave a longer-lasting impression on you. The entrance fee to the museum is 20,000 dong (about 1,000 won).

*** Gathering of information in Ho Chi Minh done with the help of Kwon Hyun-Woo

- Written by humank (Journalist; Seoul, Korea)

- Translated and revised as necessary by April Kim (Tokyo, Japan)

The numbers in parentheses indicate the respective ages of the people at the time in 1968.

This series will be uploaded on Steemit biweekly.

Click to read in korean( 이 귀여운 꼬마들의 안부를 물어달라)

Read the last article

Congratulationsdaily compilation #307!, your post was discovered and featured by @OCD in its

Gems!If you give @ocd a follow – you can find other

website for the whitelist, queue and delegation info. Join our Discord channel for more information. We usually add everyone nominated at the end of the week. :)With this nomination you will be able to use @ocdb - a non-profit distribution bot for whitelisted Steemians. Check our

SteemConnect or on Steemit Witnesses to help support other undervalued authors!We also have a witness. You can vote for @ocd-witness with

We strive for transparency!

Your post was mentioned in the Steem Hit Parade for newcomers in the following category:Congratulations @humank!

I also upvoted your post to increase its reward

If you like my work to promote newcomers and give them more visibility on the Steem blockchain, consider to vote for my witness!

Congratulations @humank! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPVote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!