Most people know why Columbus discovered America- he was actually looking for India and China. He even spent most of the rest of his life insisting that he had found them. What most people don't know, however, is why he was looking for them, and why exactly it was so important to both him and Europe.

Columbus thought that he could reach China because he thought the world's circumference was considerably smaller than it was. Ptolemy, an ancient Greek polymath, was responsible for Columbus thinking the world was smaller. His erroneous calculations were considerably smaller than the accurate calculations of his fellow ancient Greek, Eratosthenes, who accurately calculated its circumference to within 15%, which is pretty impressive for his time. Most Europeans believed Eratosthenes over Ptolemy, but Columbus was one of the few exceptions. Europeans had an approximate idea how far away India was to the East, so Columbus simply subtracted that distance from Ptolemy's estimate.

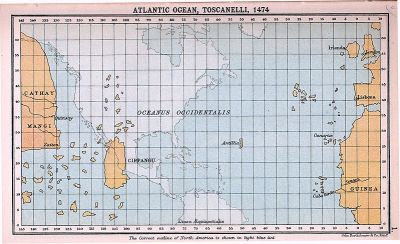

A map of what Columbus thought the world looked like overlaying a modern map. [Image source]

It should be made clear here that essentially everyone in Europe knew that the world was round- it had been common knowledge since the Ancient Greeks. The whole thing about medieval and Renaissance era people thinking the Earth was flat? Made up by some partisan historians trying to discredit the Catholic Church. That's a whole different story, though.

Why was Columbus so interested in getting to India and China, though? Well, basically put: Europe was a backwater on the stage of global politics at the time, and the Muslim states were charging them exorbitant prices for important spices and other luxury goods from India and China, the two wealthiest and most powerful nations on Earth at the time. (Well, China was an empire, but India was a bit more... complicated politically.) Portugal was funding extensive exploratory missions at the time to try and find their way around Africa to get to India, as well as to find the legendary king Prester John. Portugal would succeed at rounding Africa and reaching India less than a decade after Columbus discovered the Americas.

Prester John, the legendary Christian king. Europeans used the quest for him as a justification for many of their wider ranging explorations, as well as for some of the Crusades. [Image source]

The spice trade was HUGE business in Europe. The fortunes of Venice, the wealthiest city in Europe from the beginning of the Crusades well into the 1500s, were almost entirely built upon it- and, to be clear, those insane profits were just off the relatively constricted flow of spices coming through the Middle East. Black pepper from India made up the bulk of the trade, though frankincense from the Middle East, nutmeg from Indonesia, and many other spices, like cinnamon, were included. Later, as Venice declined, the fortunes of Genoa, Lisbon, and Amsterdam- the other great spice cities- would be determined by the vagaries of the trade as well.

It wasn't even remotely a new trade, either- a considerable portion of the total GDP of the Roman Empire went to the spice trade. So much of Rome's gold went to it, in fact, that if they had stopped exploiting new territories for revenue, the spice trade could have single-handedly driven them bankrupt. Huge hordes of Roman coins have been found all over India, and spices and goods from China have been found in Roman archaeological sites and records. (The Roman Empire is the only time before the Age of Sail where Europe wasn't a worthless backwater, and even then it was dwarfed by Imperial China.) Going back even farther, we've found archaeological evidence for Sumeria in ancient Mesopotamia having had a fairly extensive spice trade with Harappa, their enigmatic and powerful contemporaries in India.

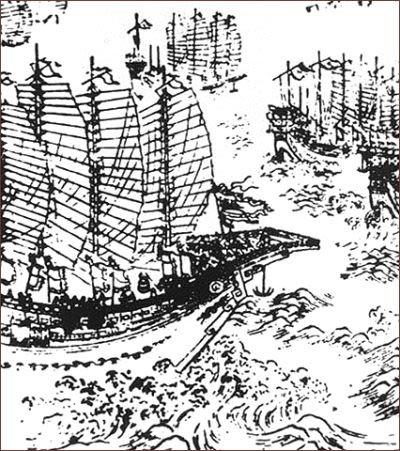

A woodcut illustration of junks from Zheng He's treasure fleets. [Image source]

Once Columbus and his successors started exploiting the Americas- and boy, did they exploit them, to the point of genocide- they began to send back all that gold, silver, and other valuables straight to Europe. Europe, however, kept descending deeper and deeper into a bullion and coin shortage. Why? Just about all of the gold and silver sent to Europe got sent straight on through the spice routes, both the old ones through the Middle East and the new ones around Africa. Europe had literally no other commodities that interested India and China.

The great powers of the Indian Ocean barely paid any attention to Europe's existence, except as mildly amusing barbarians half a world away. If they had, history would have been very, very different. If China had become aware of Europe's ambitions and future, the treasure fleets led by Zheng He could have, just from a practical standpoint, certainly reached Europe. European technology didn't accelerate significantly past Chinese technology for some time yet- though China would have been less likely to conquer Europe, and more likely to have made them an economic tributary state. Unfortunately for China, that never happened, and the treasure fleets were disbanded, never having traveled farther than East Africa. (Despite the claims of the moronic pseudohistorian Gavin Menzies, who claims they reached Europe.)

Models of one of Zheng He's treasure ships alongside Columbus' much smaller Santa Maria. Not only were the treasure fleet ships 10-20 times larger than most European vessels, the treasure fleet itself grossly outnumbered any European nation's fleet. [Image source]

All of this has important lessons for today- namely, on the topic of globalization. It is by no means a new phenomenon. Global trade and communication of ideas has been happening since the dawn of writing, if not earlier. The global trade routes dominated the economies of countries halfway around the world from each other. History is often taught as though Europeans connected the world together in the Age of Sail, introducing all these cultures together. This, frankly, is absurd. Europe was the only major center of civilization outside the Americas to be so isolated, and that was largely their own doing.

We can significantly add to our understanding of how today's globalization will affect nations, both the powerful and the weak, by looking at how the spice trade affected the world for its millennia of existence. Much of the world's economy hinged on it. Its profits helped fuel the rise of the Muslim Caliphate, filled the massive treasure chambers of India, and eventually led to Europe's global dominance. Often the study of how different parts of the world interacted is far more important than the study of those places, and yet we persist in thinking of the streams of history as isolated rather than interconnected.

Bibliography:

The Spice Route, by John Keay

Debt: The First 5000 Years, by David Graeber

Cumin, Camels, and Caravans, by Gary Paul Nabhan

The Taste of Conquest:The Rise and Fall of the Three Great Cities of Spice, by Michael Krondl

Longitude, by Dava Sobel

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spice

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_Columbus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zheng_He

Spices were the petroleum of the ancient/medieval era. During the Age of Sail, it may be argued that food preservation (meat) was the limiting factor to mercantile expansion, as wind is an unlimited propellent with the quantity in storage of food and water being the only limitation to the range of a sailing vessel. Later, with the coal-powered and petrol-driven ships, the limiting factor to range of a vessel became the quantity of fuel, rather than perishable food items. In our nuclear era, the limitations of shipping operation returned to the nutritional health of the sailors, which was overcome by Linus Pauling's elucidation of the Vitamin C chemical structure, leading to the possibility of unlimited nuclear submarine warfare and MAD.

The trade imbalance between the West and the East had profound impact upon China (don't know about India). The massive influx of silver into the Chinese economy, already short in precious metals, including copper, eventually lead to the Chinese using silver as de facto currency medium. I recall, even as a child in the 20th century, of the perception in the East of the ready availability of silver as medium for bauble manufactures.

The silver glut in China led to two Opium wars, from which the West attempted some rational trade balance to prevent the massive silver drain towards the East. More importantly, with the independence of the South American colonies from European rule, the silver flow stopped, and the Chinese, lacking a ready supply of their de facto currency medium witnessed the collapse of the Qing central government. Any polity without absolute control over their currency has not long before its inevitable collapse. From the British perspective, the Opium wars were necessary intervention to prevent their central government from devolving into the chaos Qing fell into, during the late 19th century (or maybe it is just a rationalization of the British in their unethical wars to peddle drugs that kept millions of Chinese addicted).

Nice post. The only difference I think was beside the Polynesia no country had a seafaring tradition compared to European nations.

Have you read "Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire"? Seems like it's related.

I've not read that book, no.

Plenty of nations had impressive seafaring traditions. Up until the Age of Sail (starting in the early-mid 1400s) Europeans, apart from the Norse, were actually notoriously poor sailors. The greatest maritime traditions belonged to civilizations on the Indian Ocean and based out of the Middle East up until well into the 1500s.

Which civilizations were those and what about the Greeks and Phoenicians?

Yeah, some of the Greeks, notably the Athenians, were pretty good sailors, but most were just shore huggers.

As far as near neighbors to Europe who were better sailors than them, for the most part: The Phoenicians were one of the great Middle Eastern maritime civilizations, not a European one- they lived in the Western Fertile Crescent region. The kingdom of Punt (in modern day Somalia), the Carians (from Anatolia, super ancient), the Persians, the Carthaginians, etc, etc.

Going a little farther away, the Tamil Chola Dynasty of Southern India could field truly massive fleets during their heyday. As mentioned in the post above, the Chinese were also pretty accomplished sailors- the Chinese Treasure Fleets remain the largest fleets launched by anyone until the heights of the Age of Sail. Japan and Korea also had skilled sailors and large fleets during their heyday.

Cool thanks for the information, got some stuff to look up!

If you're interested, I highly recommend Lincoln Paine's The Sea and Civlization. It's a dense, dry tome, but well worth the read.

Nice look back to history.

It looks like history repeats itself. China will eventually become most economically powerful country in the world.

Great post!

Resteemed!

Thanks!

glad I learned something on this post. nice :)

Thanks for reading!

Congratulations! This post has been chosen as one of the daily Whistle Stops for The STEEM Engine!

You can see your post's place along the track here: The Daily Whistle Stops, Issue # 27 (1/25/18)

The STEEM Engine is an initiative dedicated to promoting meaningful engagement across Steemit. Find out more about us and join us today!