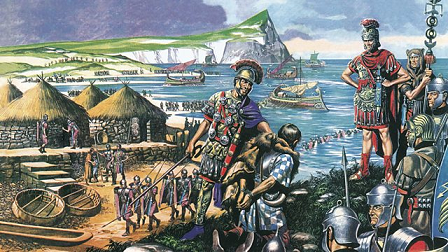

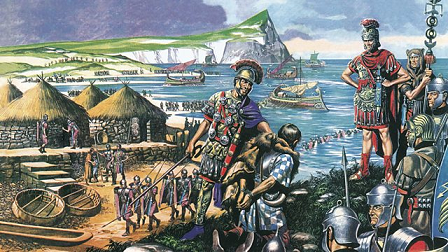

Julius Caesar first invaded Britain more than 2000 years ago, in the late summer of 55 BC, gaining little ground on the Kent coastline, mainly to punish the Belgae, who had fled there after fomenting sedition among the Gallic peoples during Caesar’s conquest of Gaul in 56 BC, now modern day France, but also to discover more about an island on the edge of the known world of which little was known, other than what had been reported by the Greek geographer Pytheas concerning the vast resources of tin that existed there.

Caesar landed in Britain with a fleet of two legions, the Legio VII and Legio X, one of which had threatened to mutiny on hearing of his intentions and after failing to gain intelligence from merchants, who traded there, regarding the inhabitants that dwelt on that mythical and misty island and were reputed to be even more savage than the Gauls, their military tactics, the geography and suitable landing-points. Defeated by strong tides and skirmishes, he was unable to put the cavalry ashore and Caesar was forced to retreat, but he was to make a more successful second expedition in 54 BC, anchoring his fleet despite again experiencing further difficulties of a strong storm and tides and damage to several of the ships. He marched his troops to Wheathampstead, in Hertfordshire to capture the hill fort of King Cassivellaunus, who was hostile to Rome, achieving a surrender after fierce fighting, withdrawing with hostages and prisoners and installing a king from the Trinovantes tribe, allied to Rome, after extracting from him an undertaking that he and other British chieftains in Eastern England would pay an annual tribute to Rome. Caesar returned to Rome having learnt that Britain was not quite the primitive island of brutal savages the Romans had previously imagined it to be (in fact, no more so than it is today.)

The decision to fully assume Britannia, as the Romans would called it, into the Roman Empire was not made until AD 43, after the death of the Belgic chieftain, Cunobelinus and the succession of his son, Caractacus, who had conquered the tribal territory of a king friendly to Rome, Verica, whose capital was Calleva Atrebatum (modern Silchester) and consisted of modern Hampshire, West Sussex and Berkshire. King Verica had fled to Rome and appealed for assistance, which was seized upon by Emperor Claudius as a pretext for invasion, believed to have begun at Richborough, in Kent. A fierce battle was to take place between the Roman landing party and an army led by Caractacus, on the banks of the River Medway, also in Kent, the Britons unable to withstand the onslaught and submitting under the might and superior tactics of the battle-hardened Roman legions. The defeated Caractacus fled to Wales, realizing the battle lost and after years of hiding to evade the Romans was captured with his family and transported to Rome in chains. The British chieftains were to be made to understand that their resistance to Roman rule was impossible and their submission inevitable, whilst chiefs, such as Cogidubnus, of the Regni, whose capital was Noviomagus Reginorum, in modern day West Sussex, took the pragmatic decision to submit and buckle-under, being richly rewarded with Roman titles and in terms of goods and monetary wealth.

(Pictured above left, The Corbridge ‘Hoard’, reconstructed Roman armour, at the Northumberland museum.)

However, with the passing of time, discontent and resistance to the Romans thickened and began to stir, later resulting in bloodshed, as the mutual benefits of the Roman presence melted-away, to be replaced by the yoke of an occupying force. When the chief of The Iceni tribe of East Anglia, Prasutagus, died in about AD 60, his request and understanding that his widow Boudicca and their two daughters would have recognized rights and protections provided to them by the Romans was cast aside. The Romans refused to accept Boudicca’s status as Queen of her tribe, she was flogged, her daughters raped and her property taken from her. The enraged Iceni, led by the red-haired, firebrand, Boudicca, led a revolt with the assistance of the Trinovantes, a neighbouring tribe, sweeping down to the Roman town of Colchester, massacring its inhabitants, destroying the temples, one dedicated to Emperor Claudius and other buildings associated with the tyranny of Roman rule. The commercial port of Londinium was to be their next target, its buildings and taverns undefended, it was swiftly burned to the ground, before attentions were turned upon Verulamium, after defeating the Legio IX Hispana, with her vast and rough army. It has been estimated that 70,000–80,000 Romans and British were killed during the revolt against those three cities and with her army depleted Boudicca was decisively defeated in battle by the Legio XIV, somewhere along the Roman road of Watling Street in the West Midlands of England, the legion marching back from Anglesey just in time to save the province. Archaeology has revealed a thick red layer of burnt debris within the bounds of Roman Londinium, dating to before AD 60 (Pictured above left, Boudicca, a tough old bird and Britain’s first Iron Lady)

Her revolt put-down, Boudicca fled the battle scene rather than be captured and tortured by the vengeful Roman army and she is thought to have killed herself at her own hand with poison, rather than be captured, or to have died of her injuries or illness, her place of her death unknown, the site of her final resting place still disputed to this day. London would be rebuilt, it grew and prospered, fortified by walls, gates and towers, it became the administrative and commercial capital of the Roman province in Britannia.

Any vestiges of tribal resistance in Britain were subdued by the failure of the revolt and the establishment of Roman provincial authority, the tribes being pushed further back to the frontiers of Wales and Scotland and the Romans completing building projects with large towns consisting of temples and basilicas, barracks and public offices, amphitheatres, baths and workshops, mostly built along the well established grid-plan as at Chichester (Noviomagus), Gloucester (Glevum) and York (Eboracum), the former headquarters of the Legio IX Hispana, defeated by Boudicca. To keep a close eye on the troublesome Welsh, Chester (Deva) was founded, headquartering the 20th Legion. Other settlements were established on top of previous arrangements of British cities, some ethic cleansing perhaps, including Lincoln (Lindum), St Albans (Verulamium) and Silchester (Calleva), the Roman walls there still extent, in places standing 14 feet in height. At Bath (Aquae Sulis) were developed the creature comforts of a spa, baths and a temple, connecting roads providing the communication between these towns, most notably Watling Street and Ermine Street, many parts of which have been consistently built upon for modern days use.

(Pictured above, Roman baths at Bath, Avon, the spa of Aquae Sulis)

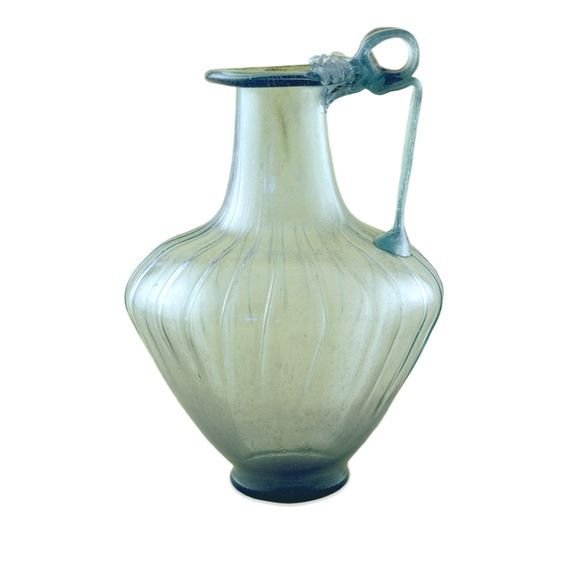

The Britons were to be gradually seduced by the trappings and accoutrements of Roman culture, becoming more Romanized, as demonstrated by the well-preserved remains of Roman villas at Chedworth, Gloucestershire and Fishbourne, a Roman mosaic floor being unearthed there in 1960 by a farmer digging a water-trench and once thought to have been occupied by King Cogidubnus, a well-to-do tribal chief who clearly benefited by his association with the Roman overlords. Archaeology has unearthed in the surrounding farmlands of these villas an array of Roman objects imported from the Continent, including ornaments of bronze and marble, figurines, silver knives, spoons, oil-lamps and candlesticks, glass jugs, dishes and bowls, earrings and bracelets. It is known that togas and leather sandals were worn and that the well-educated were taught the Latin tongue, Celtic remaining the spoken language of the poor. Wine was imported from the Roman Empire, it being considered superior to the local brews. Despite many valiant attempts, nothing much has changed in that respect.

(Pictured above, Roman mosiac at Fishbourne villa, one of the earliest and best preserved examples in Britain, discovered in 1960 by a farmer digging a water-trench)

(Pictured left, 2nd Century AD Roman glass jug found in Sittingbourne, Kent)

The British Barbarians pushed beyond the frontiers of the Roman Empire by Hadrian’s Wall, at the northern frontier and kept at bay by the strategically positioned legions and forts, such as Branodunum (Brancaster) on the east coast, and Anderida (Pevensey) in the south, the XX legion stationed at Chester (Deva) the Roman province was to enjoy a largely peaceful and untroubled existence from the conclusion of Boudicca’s revolt until the end of Roman rule there in the 4th century, due to an economic decline of the Roman Empire, a reduction in the number of troops stationed in the province and problems with the payments to the Legionnaires.

(Pictured above, Hadrian’s Wall, which once formed the Northern Frontier of the Roman empire.)

The Roman Empire was overstretched by wars on the Continent and in economic decline, the province crumbled and the long suppressed natives on the margins chose this moment of weakness to overrun Hadrian’s Wall from the north in 368, its turrets and towers offering little resistance. The islanders were left to resolve their own destiny and fight for themselves against the Viking and Saxon invasions that would follow.

https://steemit.com/bearshares/@bearbear613/you-have-been-warned-or-you-will-be-scammed-bearshares

Bearshares SCAM

Hello @sandwichbill! This is a friendly reminder that you have 3000 Partiko Points unclaimed in your Partiko account!

Partiko is a fast and beautiful mobile app for Steem, and it’s the most popular Steem mobile app out there! Download Partiko using the link below and login using SteemConnect to claim your 3000 Partiko points! You can easily convert them into Steem token!

https://partiko.app/referral/partiko

Congratulations @sandwichbill! You received a personal award!

Click here to view your Board

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness and get one more award and increased upvotes!

Congratulations @sandwichbill! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!