A Country’s Beating Heart

An amalgam of history, hybrid communities, crime and politics, Karachi defies the imagination – and despair.

If historical references are to be believed, Karachi’s known history dates back to almost 500 BC. Its natural harbour was used by indigenous fishermen of the area since prehistory. Then came the ancient Greeks who called this port by many names, including Krokola. Alexander the Great is said to have encamped here after his campaign in the Indus Valley, and then before he embarked with his fleet on his return to Babylonia. His admiral Nearchus is said to have sailed from the ‘Morontobara’ port – probably the modern Manora Island near the Karachi harbour.

During the time of Muhammad bin Qasim, the Arabs knew this port as Debal where the Umayyad general landed in AD 712 for his invasion of Sindh and regions along the Indus River, overthrowing the unpopular Hindu king, Raja Dahir, and introducing Islam in the subcontinent.

Abdullah Shah Ghazi, one of the greatest Sufi saints of Sindh and also Ahl al-Bayt (from the family of Prophet Muhammad PBUH) arrived here from Kufa as a horse merchant-cum-trader in 760. Known for his bravery, he was called Ghazi and was buried along with his brother where his shrine now stands.

One of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent’s famous Ottoman admirals, Seydi Ali Reis mentions Debal and Manora Island in one of his books Mir’ât ül Memâlik (the Mirror of Countries) in 1554. Debal was fortified during the Mughal period to ward off invasions by Portuguese colonial ships, but it was attacked in 1568 by Portuguese Admiral Fernão Mendes Pinto in an attempt to destroy the Ottoman ships anchored at the Debal port.

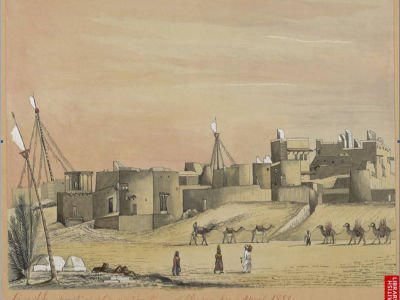

Sindh, part of the native town of Kurrachee, 1851.’ Water-colour of Karachi by Henry Francis Ainslie (c.1805-1879)Sindh, part of the native town of Kurrachee, 1851.’ Water-colour of Karachi by Henry Francis Ainslie (c.1805-1879)

The settlement at the port became an integral part of Sindh’s Talpur dynasty in 1720 and grew into a village by the name of Kolachi-jo-Goth (village of Kolachi) and began trading with Muscat and the Persian Gulf in the late 1720s. In order to protect their village, the Sindhi sailors imported cannons from Oman and Muscat and the local populace constructed a small fort with two gateways. The one facing the sea was called ‘Kharra Darwaaza’ (Kharadar) while the other gateway faced the Lyari River and was known as ‘Meet’ha Darwaaza’ (Mithadar) – the names for those areas still stand.

The name Karachee first appeared on a document in 1742 of a Dutch merchant ship `de Ridderkerk’ belonging to the Dutch East India Company when it was shipwrecked along its coast.

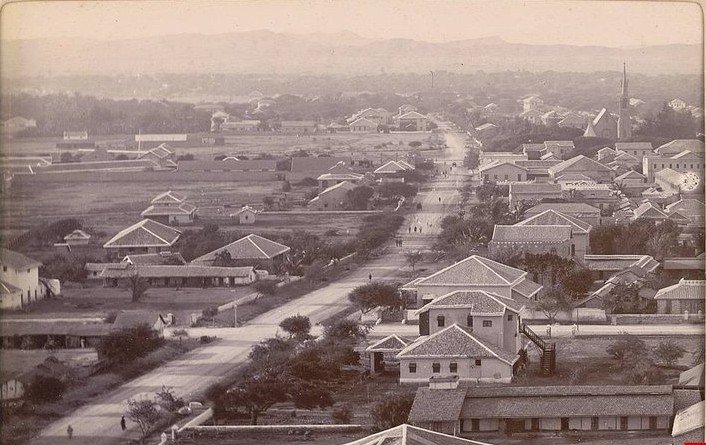

After a few expeditions, the British East India Company, captured the town, two days after the Royal navy ship HMS Wellesley anchored off Manora Island on February 1, 1839. Karachi gained further importance after Sindh’s conquest by Major General Charles James Napier in 1843, and went on to become part of the British Indian Empire.

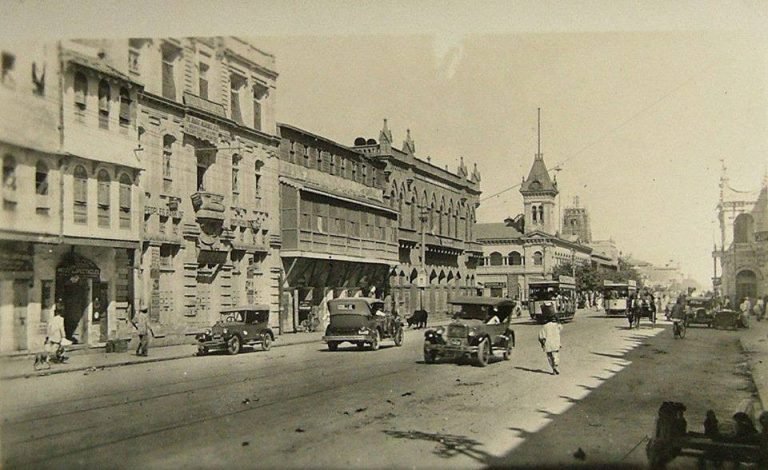

During the same year, when troops of Company Bahadur arrived, it established a new military cantonment area meant only for the white’ with limited access to the local population. The city was also divided into two – thewhite’ part of town comprised the Frere Hall, Masonic Lodge, Sindh Club, the Governor’s House, Staff Lines, and the Collectors Kutchery’ (Law Court), and whites shopped at Saddar bazaar area and the Empress Market. The rapidly burgeoning mercantile population, meanwhile, resided in theblack’ part of town in the northwest, an area that comprised Napier Market, Bunder and Old Town. They shopped in the Serai Quarter of the town.

The name Karachee first appeared on a document in 1742 of a Dutch merchant ship `de Ridderkerk’ belonging to the Dutch East India Company when it was shipwrecked along its coast.

After a few expeditions, the British East India Company, captured the town, two days after the Royal navy ship HMS Wellesley anchored off Manora Island on February 1, 1839. Karachi gained further importance after Sindh’s conquest by Major General Charles James Napier in 1843, and went on to become part of the British Indian Empire.

During the same year, when troops of Company Bahadur arrived, it established a new military cantonment area meant only for the white’ with limited access to the local population. The city was also divided into two – thewhite’ part of town comprised the Frere Hall, Masonic Lodge, Sindh Club, the Governor’s House, Staff Lines, and the Collectors Kutchery’ (Law Court), and whites shopped at Saddar bazaar area and the Empress Market. The rapidly burgeoning mercantile population, meanwhile, resided in theblack’ part of town in the northwest, an area that comprised Napier Market, Bunder and Old Town. They shopped in the Serai Quarter of the town.

When Napier left, Karachi was made part of the Bombay Presidency. And in less than 175 years this small fishing village has now become a sprawling megalopolis, with nearly 23 million inhabitants.

The British Raj realised Karachi’s strategic importance very early on, and embarked on large-scale modernisation of the city. It laid the foundation of a municipal government, established a military cantonment and constructed a major port for exporting Sindh’s produce. Consequently, new businesses brought prosperity, and Karachi was transformed into a city. Ergo Napier’s famous quote long after he left Sindh: “Would that I could come again to see you in your grandeur!”

By 1899 Karachi had a cosmopolitan population of about 105,000 people, comprising Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Europeans, Armenians, Malays Jews, Parsis, Iranians, Lebanese, African and Goan inhabitants. By 1914, Karachi was the British Empire’s largest grain-exporting city. An aerodrome built in the city in 1924 became the main airport of entry into the British Raj, and the metropolis came to be described as the `Paris of Asia.’

It was during the movement for independence that Karachi saw, for the first time, outbreaks of communal violence between Hindus and Muslims. When it became the capital after Pakistan’s Independence in 1947, it witnessed the first mass migration as its Hindu and Sikh residents migrated to India, to be replaced by Muslim refugees who had fled that country. On the eve of independence, Karachi’s population exceeded 400,000.

North Nazimabad was developed as a residential area for federal government employees and was ranked as the most modern town planned in Karachi, designed in the late ’50s by Italian planners and architects, Carlo Scarpa and Aldo Rossi. And despite the capital being shifted to Islamabad in 1958, it didn’t stop the city from remaining the economic jugular of the country in the 1960s and beyond – and even to date. Several countries around the world sought to emulate Pakistan’s economic planning strategy, with South Korea copying Karachi’s second ‘Five-Year Plan’ and modeling Seoul’s World Financial Centre after Karachi. It was during this time that Karachi earned the sobriquet ‘City of Lights.’

Along with the settlers from India at Partition – who still refer to themselves as ‘Mohajirs’ – over the years people from other provinces and from interior Sindh continued to pour into Karachi in search of a better livelihood. And in 1971, another wave of migration took place when former East Pakistan broke away to become Bangladesh. Thousands of Biharis and Bengalis arrived in the city, and today Karachi is home to between one and two million migrants from Bangladesh. The prolonged Soviet war and occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s and 1990s brought thousands of Afghan refugees into the country and many of them settled in Afghan bastis on the outskirts of Karachi. They brought with them a weapons and drugs culture, and changed the ethos of the city forever.

Then the mega floods of 2010 and 2011 happened. They inundated one fifth of the country and brought in thousands of flood refugees from interior Sindh. Many who were housed in Labour Square were never to return to their villages, as many were poor tenant farmers who saw Karachi as a city of growth and opportunity.

And as the ranks swelled, so did the problems faced by the city’s original dwellers. The ‘City of Lights’ became a ‘city of blights’ – but even on its darkest day, there remained a glimmer of light, a ray of hope. That was, and is, the insurmountable resilience and never-say-die spirit of the people who call Karachi home.

it's really intrested history dear

Thanks Bro

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://newslinemagazine.com/magazine/brief-history-karachi/

Nice article for my dear city!