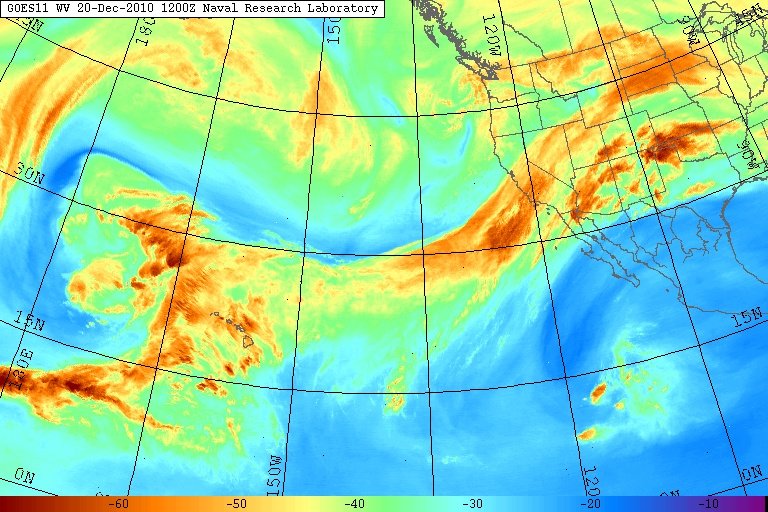

Atmospheric Rivers (ARs) are relatively narrow regions in the atmosphere and are responsible for most of the horizontal transport of water vapor outside of the tropics. While ARs come in many shapes and sizes, those that contain the largest amounts of water vapor, the strongest winds, and stall over watersheds vulnerable to flooding, can create extreme rainfall and floods.

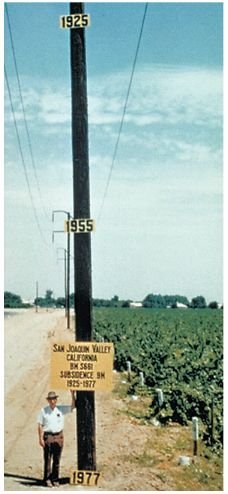

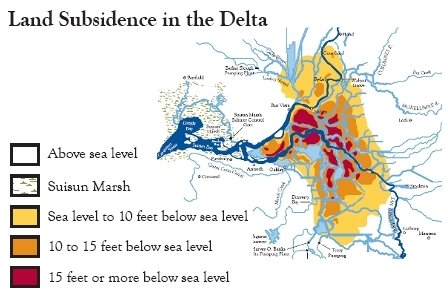

Thirty-five inches fell in the 30 days between December 24, 1861, and January 23, 1862. The Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys, a combined region 250 to 300 miles long and an average of at least twenty miles wide, or probably three to three and a half million acres, was totally under water.

Native Americans knew the Sacramento Valley as an inland sea when the rains came. Ancient storytellers told of water filling the valley from the Coast Range to the Sierra.

In early December, the Sierra Nevada experienced a series of cold arctic storms that dumped 10 to 15 feet of snow, and these were soon followed by warm atmospheric rivers storms. The series of warm storms swelled the rivers in the Sierra Nevada range so that they became raging torrents, sweeping away entire communities and mining settlements in the foothills—California’s famous “Gold Country.”

Sixty-six inches of rain fell in Los Angeles that year, more than four times the normal annual amount, causing rivers to surge over their banks, spreading muddy water for miles across the arid landscape. Large brown lakes formed on the normally dry plains between Los Angeles and the Pacific Ocean, even covering vast areas of the Mojave Desert. In and around Anaheim, , flooding of the Santa Ana River created an inland sea four feet deep, stretching up to four miles from the river and lasting four weeks.

Finance-wise, the storms “bankrupted the state, destroyed the ranching industry, drowned 200,000 head of cattle [and] changed California from a ranching economy to a farming economy” in essentially one stroke, seismologist Lucy Jones told NPR in 2013. The state capital temporarily moved to San Francisco, as Sacramento was navigable only by boat.

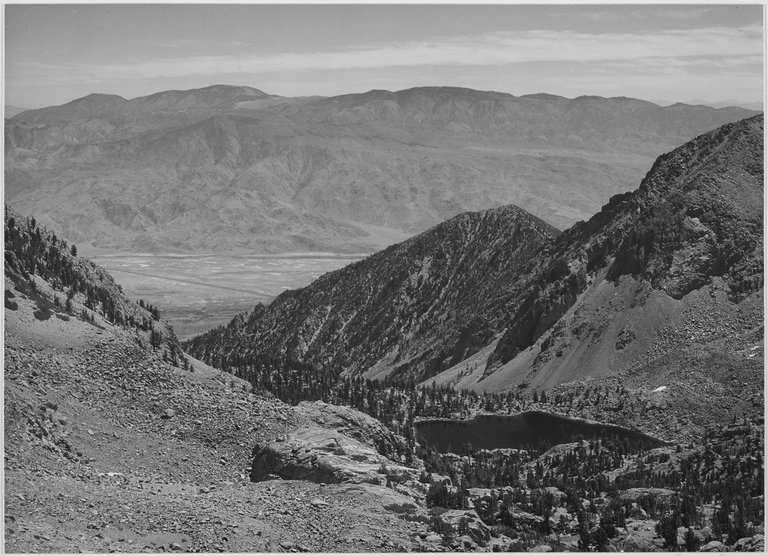

The Owens River valley had been the home of the Paiute Indians for many years; Linguistically, these Indians spoke the Shoshone language and are sometimes referred to as the Paiute Shoshones. They were primarily food gatherers and farmers. They lived on Pinyon Pine nuts, wild hyacinth tubers and yellow nutgrass tubers as well as the larva of a fly that laid its eggs upon the surface of saline Owens Lake. They also lived on deer, Desert big horn sheep, fish and small game.

The winter of 1861-62 was one of the most severe in the history of the Owens Valley. The plight of the Paiutes was exceedingly bad. The bad weather had driven away almost all of the game and had killed what little game remained. Cattle were now beginning to forage on the Indian's fields of wild hyacinth and yellow nutgrass. It seemed only natural to the Paiutes that the cattle could be killed for their own use, since the cattle were feeding on their fields.

But disputes arose as settlers poured into the valley and began ranching on the tribe's pasturelands. U.S. troops were sent to protect the settlers and the land and water they had effectively stolen from the Paiutes. By 1860, the Paiutes' land had been overrun with cattle and sheep. Tensions spiked when Paiutes took down a settler's cow or ox to eat during the severe winter of 1861. During the Owens Valley Indian War, between 1861 and 1866, ranchers — backed by troops — and the Paiutes tried to wipe each other out. Paiute homes and stores of food were destroyed. Paiutes fought back with bows and arrows, and a few guns.

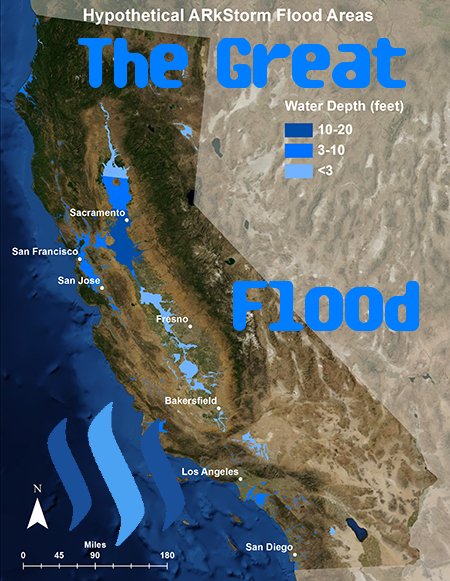

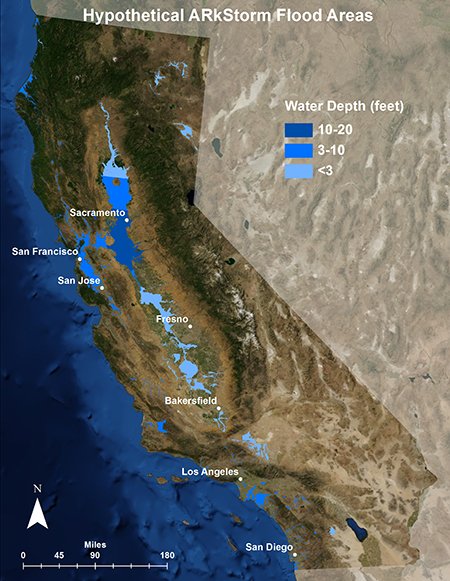

The scenario was dubbed ARkStorm — named for Atmospheric River 1,000 Storm — and published in 2011 after input from more than 100 experts from public and private sectors. The scenario envisions a pounding of California by a series of “atmospheric rivers” — long plumes of water vapor that can pour over the West Coast and hold as much as 15 times the liquid water flowing out of the Mississippi River’s mouth.

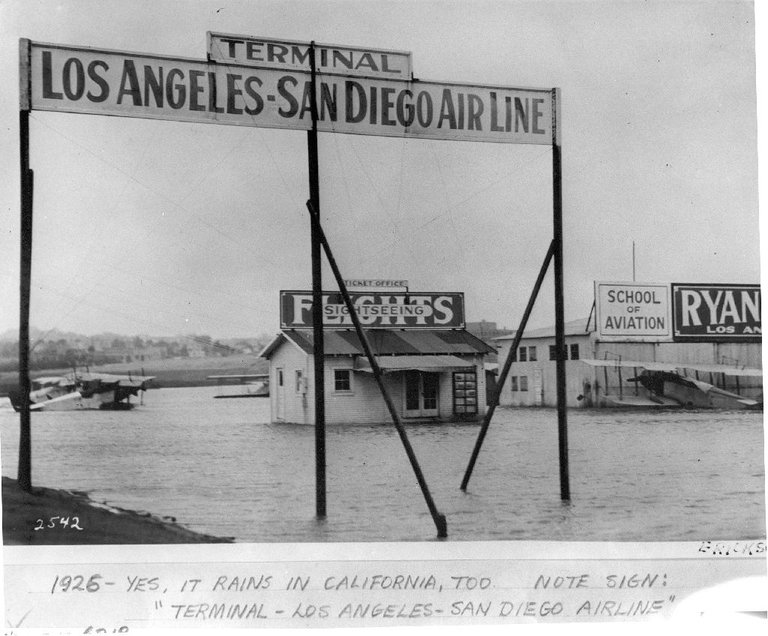

The rains that swept southern California in mid-January, 1916, converted the streams into torrents that overran their banks and devastated wide areas of the most fertile land of the State. The rains were heaviest and the floods most disastrous in San Diego County, but they were also very heavy in parts of Riverside, San Bernardino, Los Angeles, and Ventura counties, and they wrought widespread ruin throughout the region that extends southward from Santa Clara River to the Mexican boundary, and westward from the north-south ranges of San Bernardino and San Diego counties to the ocean. For nearly a month San Diego County was practically cut off from communication with the rest of the State.

"Geologic evidence shows that truly massive floods, caused by rainfall alone, have occurred in California about every 200 years. The most recent was in 1861, and it bankrupted the state," US Geological Survey hydrologist, Michael D. Dettingeris, and paleoclimatologist B. Lynn Ingram from the University of California, Berkeley wrote in a 2013 Scientific American report. "It has now been 150 years since that calamity, so it appears that California may be due for another episode soon."

Wow great article. I did not know central California could flood like that. Now I am going to go buy a boat.

That’s amazing history. I lost a colleague and his daughter in the flooding this year.

Cal has so much history!

That is some really interesting history! Thanks for sharing all that info. I drive by the old site of Eldoradoville every time I drive up into the East fork, all the history up there is so cool.