Yesterday's post ended with Stage four. The Age of Affluence

Per Sir John Glubb's essay, by this time in the life cycle of empires, historically speaking, they've passed their 'High Noon".

This brings them into:

Stage five. The Age of Intellect.

The great wealth of the nation is no longer needed to supply the mere necessities, or even the luxuries of life. Ample funds are available also for the pursuit of knowledge.

Your first thought might be that this will usher in an even greater age of wealth and prosperity for the empire.

The merchant princes of the Age of Commerce seek fame and praise, not only by endowing works of art or patronising music and literature. They also found and endow colleges and universities. It is remarkable with what regularity this phase follows on that of wealth, in empire after empire, divided by many centuries.

He gives the example of Malik Shah, the Seljuk sultan of the 11th century Arab empire who developed a passion for building colleges and universities even after the empire had begun to decline.

Whereas a small number of universities in the great cities had sufficed the years of Arab glory, now a university sprang up in every town.

Surely all of this widespread knowledge has to lead to a renaissance period of renewal and growth, what with all that fancy lernin' goin' on?

The ambition of the young, once engaged in the pursuit of adventure and military glory, and then in the desire for the accumulation of wealth, now turns to the acquisition of academic honours.

The study of science, technology, and the liberal arts are all, in and of themselves, truly legitimate and beneficial activities.

What other effect can they possibly have, other than enrich the minds of the empire and with it, the empire itself?

Glubb rhetorically asks why these activities couldn't be carried out at the same time as the commerce and affluence ages, although in moderation.

He then answers, that it simply never seems to happen that way.

There are so many things in human life which are not dreamt of in our popular philosophy. The spread of knowledge seems to be the most beneficial of human activities, and yet every period of decline is characterised by this expansion of intellectual activity.

In fact, he goes on to give the example of the Arab and Persian intellectual movements not really coming into their prime until after their political and imperial collapses had already occurred.

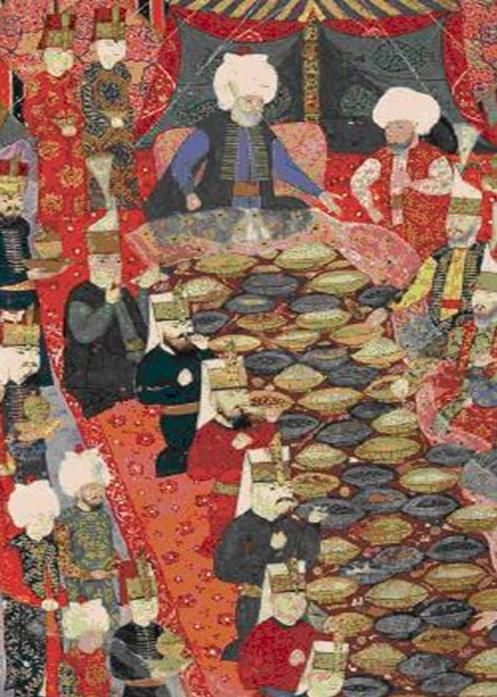

Thereafter the intellectuals attained fresh triumphs in the academic field, but politically they became the abject servants of the often illiterate rulers. When the Mongols conquered Persia in the thirteenth century, they were themselves entirely uneducated and were obliged to depend wholly on native Persian officials to administer the country and to collect the revenue.

They retained as wazeer, or Prime Minister, one Rashid alDin, a historian of international repute. Yet the Prime Minister, when speaking to the Mongol II Khan, was obliged to remain throughout the interview on his knees. At state banquets, the Prime Minister stood behind the Khan’s seat to wait upon him.

If the Khan were in a good mood, he occasionally passed his wazeer a piece of food over his shoulder.

Have you ever wondered where the expression, "Dude, throw me a bone" came from?

This may very well be the origin.

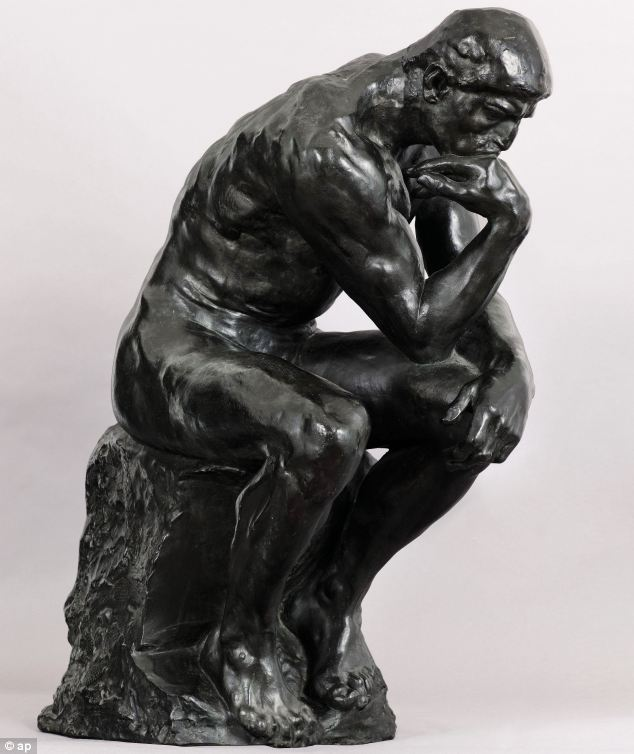

And what are the effects of all of this knowledge, of all of these intellectuals and their deep thinking and pondering?

Men are interminably different, and intellectual arguments rarely lead to agreement. Thus public affairs drift from bad to worse, amid an unceasing cacophony of argument. But this constant dedication to discussion seems to destroy the power of action.

Amid a Babel of talk, the ship drifts on to the rocks.

Endless argument by our "leaders" while the bus drives off a cliff.

Does that sound at all familiar?

Glubb hints at the underlying reason for this seemingly counter-intuitive turn of events.

Thus we see that the cultivation of the human intellect seems to be a magnificent ideal, but only on condition that it does not weaken unselfishness and human dedication to service. Yet this, judging by historical precedent, seems to be exactly what it does do.

Could it be that people become too smart to work for the common good?

Do we become more selfish, the more "educated" we become?

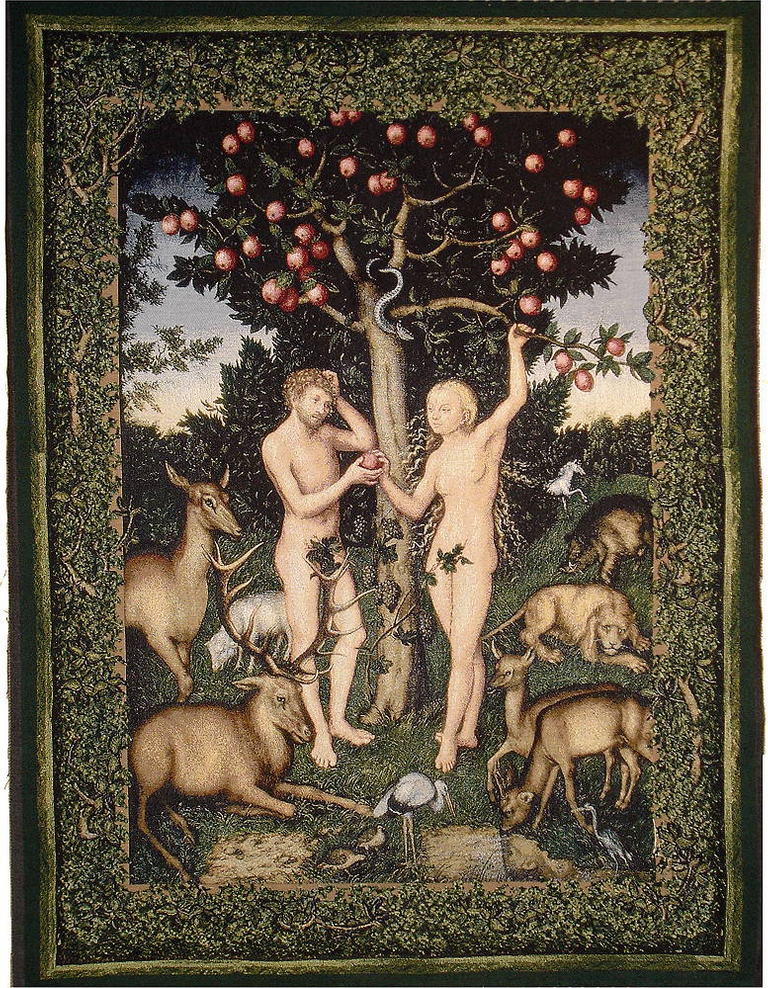

Does partaking of the fruit from the tree of knowledge ... oops, a little off course there.

All of these smart, highly educated intellectuals also rarely agree so you wind up with what Glubb calls "Civil dissensions".

Another remarkable and unexpected symptom of national decline is the intensification of internal political hatreds. One would have expected that, when the survival of the nation became precarious, political factions would drop their rivalry and stand shoulder-to-shoulder to save their country.

Nope, not gonna happen.

Republicrats and Demopublicans are never going to work together.

In the fourteenth century, the weakening empire of Byzantium was threatened, and indeed dominated, by the Ottoman Turks. The situation was so serious that one would have expected every subject of Byzantium to abandon his personal interests and to stand with his compatriots in a last desperate attempt to save the country. The reverse occurred. The Byzantines spent the last fifty years of their history in fighting one another in repeated civil wars, until the Ottomans moved in and administered the coup de grâce.

Say Goodnight.

There's another interesting phenomenon that comes towards the end of empires; the influx of foreigners into the capital city.

And before you get all xenophoby, listen to how he explains it, quite simply and without prejudice.

This problem does not consist in any inferiority of one race as compared with another, but simply in the differences between them.

In the age of the first outburst and the subsequent Age of Conquests, the race is normally ethnically more or less homogeneous. This state of affairs facilitates a feeling of solidarity and comradeship. But in the Ages of Commerce and Affluence, every type of foreigner floods into the great city, the streets of which are reputed to be paved with gold.

Now where have I heard that saying before, "streets paved with gold"?

If you can't understand why this wonderful cultural diversity could possibly be bad:

First, their basic human nature often differs from that of the original imperial stock. If the earlier imperial race was stubborn and slow moving, the immigrants might come from more emotional races, thereby introducing cracks and schisms into the national policies, even if all were equally loyal.

That sounds rather matter of fact, I don't sense anything inherently racist about it.

In fact, he goes so far as to pretty much call the "original imperial stock" lazy.

Second, while the nation is still affluent, all the diverse races may appear equally loyal. But in an acute emergency, the immigrants will often be less willing to sacrifice their lives and their property than will be the original descendants of the founder race.

Not my fight, why should I care?

Third, the immigrants are liable to form communities of their own, protecting primarily their own interests, and only in the second degree that of the nation as a whole.

Who can blame them if they don't want to assimilate?

We wouldn't want to appropriate their culture or force them to be like us now would we?

Perfectly understandable.

Fourth, many of the foreign immigrants will probably belong to races originally conquered by and absorbed into the empire. While the empire is enjoying its High Noon of prosperity, all these people are proud and glad to be imperial citizens. But when decline sets in, it is extraordinary how the memory of ancient wars, perhaps centuries before, is suddenly revived, and local or provincial movements appear demanding secession or independence.

Um, you're not still mad about that whole "being conquered" thing are you?

In a move as if he realized people would label him a racist, xenophobe, white supremecist, etc. Glubb re-iterates at the end of this section:

Once more it may be emphasised that I do not wish to convey the impression that immigrants are inferior to older stocks. They are just different, and they thus tend to introduce cracks and divisions.

The next post will begin The Age of Decadence

Here's a link to The Fate of Empires, An Overview (Part 1)

And now I know where the phrase "throw me a bone" might have originated from haha

Such a well written piece, and I specially enjoyed the Adam/Eve tapestry image you used! I'm going to read the other parts when I get a chance today!

Thank you @artdellavita I'm enjoying myself.

This post received a 3.3% upvote from @randowhale thanks to @theblindsquirl! For more information, click here!

Congratulations! This post has been upvoted from the communal account, @minnowsupport, by theblindsquirl from the Minnow Support Project. It's a witness project run by aggroed, ausbitbank, teamsteem, theprophet0, and someguy123. The goal is to help Steemit grow by supporting Minnows and creating a social network. Please find us in the Peace, Abundance, and Liberty Network (PALnet) Discord Channel. It's a completely public and open space to all members of the Steemit community who voluntarily choose to be there.

If you like what we're doing please upvote this comment so we can continue to build the community account that's supporting all members.

This post was resteemed by @resteembot!

Good Luck!

Learn more about the @resteembot project in the introduction post.

Very interesting article. With education, people do not necessarily become kinder or more human. It is the values that are inculcated through the education system that makes us better human beings.

That can work in the opposite direction too if the educational system's purpose is to create obedience and subservience.

I think understanding leads to more kindness and humanitarian behavior. I've seen good examples of that here and hope it can spread.

That's true. That is why I am trying to spread positivity here one post at a time. Do check out my profile.