They say that V for Vendetta was the most popular graphic novels in recent time but it's implication of Guy Fawkes was not absolutely correct.

Remember, remember the fifth of November is the opening line of the British traditional rhyme. It is repeated in Alan Moore's V for Vendetta - a politically motivated graphic novel, which heavily symbolizes the real historical persona of Guy Fawkes.

Undoubtedly a classic of its genre, the story's ideas and anarchistic ideals have been further popularized by hacktivists Anonymous. Their public appearances show members wearing a V for Vendetta style Guy Fawkes mask.

The same mask is worn, in the graphic novel, by the protagonist, V. He strongly advocates broadening the mind through learning and cultural exposure. Yet, perhaps a little ironically, Moore's telling implies a skewed version of the real life events, which led to the capture and execution of Guy Fawkes.

In short, it does anything but remember the reality of November 5th 1605.

An Anonymous Activist: Guy Fawkes in V for Vendetta

Alan Moore doesn't directly rewrite history in his treatment of Guy Fawkes. In fact, the actual historical figure is only mentioned a couple of times. However, the fact that V dresses as Guy Fawkes, throughout V for Vendetta, implies a motivation and ideology, which simply didn't exist in the 17th century activist.

In the opening sequence, V quotes the rhyme, Remember, Remember the Fifth of November, to Evey Hammond, as they watch Big Ben and Westminster explode on the horizon. It is possible to read too much into V's quotations.

During the course of the graphic novel, V quotes everyone from William Blake to Tamla Motown. No-one would argue that V represents Martha Reeves, beyond the fact that he, like Anonymous, styles himself as being everyone.

But coupled with his attire, this scene firmly establishes a connection between V and Guy Fawkes at the very outset. His actions often involve him being underground and/or blowing up the British seats of government.

The ending demonstrates a clear link between them, with similar fates in store at the hands of the law enforcers.

A second overt mention of Guy Fawkes comes from a television broadcast. Going on air on November 5th, V tells his audience, 'Almost four hundred years ago tonight, a great citizen made a most significant contribution to our common culture.'

He then references the British tradition of Bonfire Night and fireworks, as he adds, 'It was a contribution forged in stealth and silence and secrecy, although it is best remembered in noise and bright light.'

In 2006, Warner Brothers made a film version of V for Vendetta. Here, the link between V and Guy Fawkes is made even before the opening credits. Evey's voiceover speaks the full rhyme before a visual dramatization of the discovery, capture and execution of Guy Fawkes in 1605.

The monologue states that we should remember the idea, not the man, because a man can fail. Then it segues nicely into telling us that 400 years later, the idea was resurrected in V.

What V for Vendetta Implies About Guy Fawkes

In the graphic novel, V is an anarchist seeking to overturn the Fascist British government. He doesn't seek to become a leader. He merely wants a vacuum to open, wherein the apathetic British people would have to think for themselves.

There should be no leaders, but people should do as they please. In his ideals of anarchy, he explains that voluntary order would ensue in an open society.

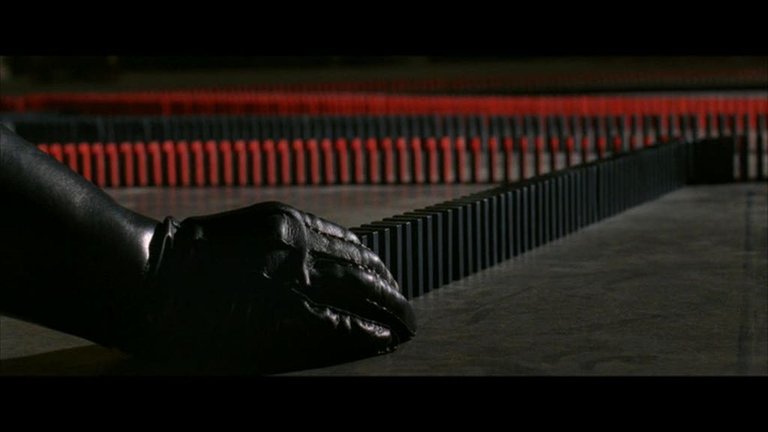

He envisages himself as the person who flicks the domino, that sparks a chain reaction. His activism would be inspirational causing the ordinary people to flock to his cause, then change the world through their own actions.

This is even more apparent in the film version, when thousands of people don the same Guy Fawkes outfit as V and march through the streets.

Moreover, the bonfires and fireworks of November 5th are seen as the ultimate symbol of rebellion. The real Guy Fawkes would be horrified.

Gunpowder Treason: The Historical Guy Fawkes and Bonfire Night

Contrary to the imagery in V for Vendetta, the real Bonfire Night is not a glorification of rebellion. In fact, it was an annual anti-Catholic rally, initiated by the monarchy and government, and made law in the spring of 1606.

The historian Professor Ronald Hutton wrote about Bonfire Night, in The Stations of the Sun, stating that the original bonfires burned the Pope and Satan in effigy, as well as Guy Fawkes himself.

It was the ruling elite who also devised the rhyme that is so commonly quoted.

The anti-Catholic sentiment also gives a clue to the nature of Guy Fawkes's ideology. He was a devout Catholic extremist, who sought to blow up the government on its opening session.

Due to the ceremonial nature of this meeting of Parliament, the entire Houses of Commons and the Lords would have been present, as well as King James (VI) I, Queen Anne and both princely heirs to the throne, who were children at the time. In short, the entire ruling elite would have been destroyed in one audacious explosion.

So far, nearly so V for Vendetta, give or take the religion. But where V wanted anarchy, Guy Fawkes was party to a plot which sought to reinstate Catholicism in Britain. He was only one of thirteen people, not the lone freedom fighter of the graphic novel; nor was he even the brains behind the operation. That was Robert Catesby. Fawkes was simply the first to be caught.

If they had their way, then November 5th 1605 would have been remembered for the placing of a fundamentalist Catholic government over Britain. The population would have been forced to convert or else suffer fates similar to those which V fought against.

Alan Moore's graphic novel is a brilliant political diatribe, but beware citing it as historically accurate. Both Guy Fawkes and V fought against their governments, but with very different motivations.