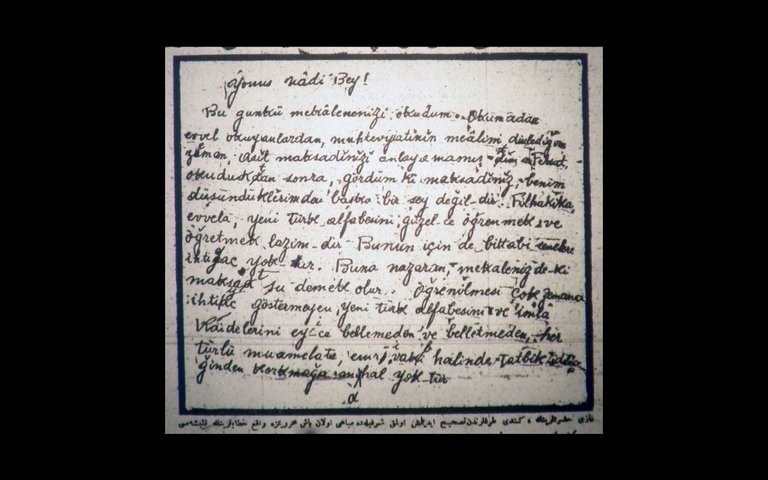

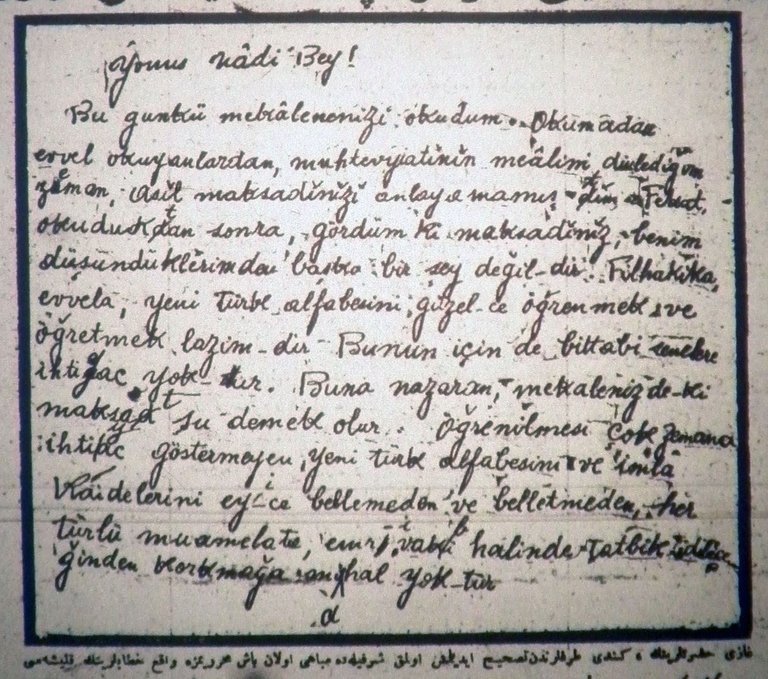

(A letter to the editor, Cumhuriyet, 19 August 1928, no. 1537, page 1.)

English

Mr. Yunus Nadi!

I read your article from today. When I heard about the meaning of its content from those who had read it before reading it for myself I did not understand your real objective. But after reading it I saw that your intentions were no different than my own. It is truly necessary to thoroughly learn and teach the new Turkish alphabet. Naturally, years [of work] will not be necessary for this. In regards to this, your article’s message is the following: because the new Turkish alphabet and rules of spelling, which will not require much time to learn, will be adapted before they are learned or taught and [only] once all of their possible applications are determined, there is nothing to be afraid of.

Comments:

On the cover of today’s issue of the daily newspaper Cumhuriyet (“The Republic”), the editor and proprietor, Yunus Nadi, published an article about a lesson he attended in the presence of president Mustafa Kemal. Embedded in this article is a hand-written letter from Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) which Yunus Nadi recently received. The letter comments on an article published by the editor on a previous day and expresses agreement with the editor’s opinions about the subject of alphabet reform.

Indeed, at this time in history plans for alphabet reform are picking up speed. Consequently, outlines for the new alphabet as well as designs for its mass implementation are the subject of daily discussions and coverage in the press. Alphabet reform, which would take effect at the end of the year, was a nation-wide effort to transition out of using the Arabic letters for written communication in favor of a Latinized alphabet, which was argued to be easier to learn than the Arabic script, thus, contributing to mass literacy (among other reasons and claims).

What is most striking about this letter is the President’s handwriting and his effort to lead by example. Here, Mustafa Kemal, or “the Gazi,” uses a newly developed version of the Latin letters to represent Turkish sounds and language. At this point, using the Arabic letters that he was accustomed to would have been easier, but to set an example and make a point, he chose to use the new letters. What is the point? That the new letters will be easy to learn and adapt to the Turkish language. Of course, the Gazi already new the Latin letters from his experience with the French language but it is eye-opening to see the process of spelling, punctuation, and diacritical markings in this early “draft.” Since the Turkish language had never been written with these letters, there existed no standards for spelling yet. Thus, many early writings show the growing pains of figuring out proper spelling based on how words were pronounced (which varied from region to region) since the new Latin letters would be applied on a phonetically consistent basis.

Today in 1920s Turkey has covered other content related to alphabet reform where other facets of the change are explored. See:

Disseminating Knowledge of the New Alphabet

(Entire page, Cumhuriyet, 19 August 1928, no. 1537, page 1.)

Hello @yasemin-gencer, thank you for sharing this creative work! We just stopped by to say that you've been upvoted by the @creativecrypto magazine. The Creative Crypto is all about art on the blockchain and learning from creatives like you. Looking forward to crossing paths again soon. Steem on!