Chaobai River: An amazing Fishing Spot in the City

Chaobai River: An amazing Fishing Spot in the City

Yeah, the defamation law is everywhere, and until you are spreading positivity I never use bad words or comments regarding any person, any nation, or any religious belief; and I have my every word in the blockchain, so I am much aware of it. And I don't post any politics, or sensitive issues here also. You should be also very careful about those things, spreading negativity is a big crime, and hiding someone's mistakes is a good virtue when it is necessary. Thanks for your concerns regarding these legal issues.

I gained a lot of inspiration and wisdom while talking with Hassan, a handsome friend who came to East Asia from the Indian subcontinent!😄

Since ancient times, many East Asian men have admired the boundless imagination and creativity of men from the Indian subcontinent!

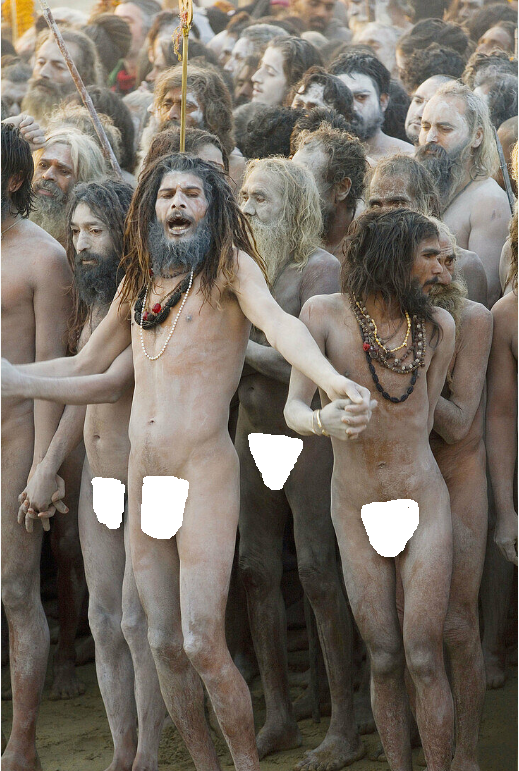

Modern East Asian men are shocked and astonished when they see countless men naked on the banks of the Ganges!😨

Those men were Hindu saints and said that if they bathed in the Ganges River, they would go to heaven.

I've studied the history of many countries and peoples around the world, but it seems like people like that probably came from outer space!😆

I thought maybe Hassan is a devout Muslim and would not agree with what they said!

Hindus call such naked men gurus and respect them as saints.

I wonder if there are naked men like that in Bangladesh!

I think those naked men are either geniuses or psychopaths!😆

I think that because those naked men bathe and defecate in the Ganges River, the environment has become extremely polluted!😁

So, I believe that the Ganges River is not a passage to heaven, but a source of disease!

Perhaps Hassan would disagree with me?

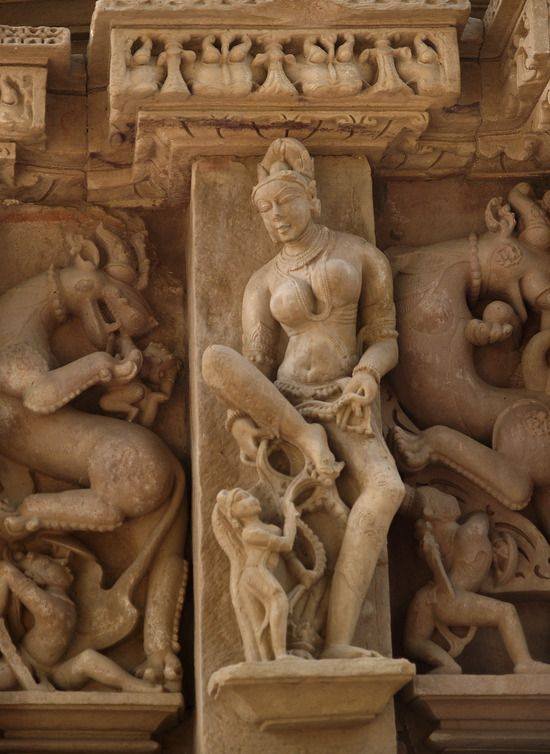

However, it is amazing that those naked men created the Kamasutra 2500 years ago!

Many modern East Asian men admire and understand Indian civilization through Kamasutra!

1. Chinese rulers who married Indo-Aryan women!

The influence of Indian civilization on the birth of East Asian civilization!?

However, Indian Buddhist and Hindu mythology and literature have also become very popular with East Asians!

In a previous life, as a woodpecker, the Buddha removes a bone from the throat of a lion, Amaravati style, c. 175-225 CE

In a previous life, as a woodpecker, the Buddha removes a bone from the throat of a lion, Amaravati style, c. 175-225 CE

The Jātaka (Sanskrit for "Birth-Related" or "Birth Stories") are a voluminous body of literature native to the Indian subcontinent which mainly concern the previous births of Gautama Buddha in both human and animal form. Jataka stories were depicted on the railings and torans of the stupas. [1][2] According to Peter Skilling, this genre is "one of the oldest classes of Buddhist literature."[3] Some of these texts are also considered great works of literature in their own right.[4]

Vessantara Jataka, Sanchi

In these stories, the future Buddha may appear as a king, an outcast, a deva, an animal—but, in whatever form, he exhibits some virtue that the tale thereby inculcates.[5] Often, Jātaka tales include an extensive cast of characters who interact and get into various kinds of trouble - whereupon the Buddha character intervenes to resolve all the problems and bring about a happy ending. The Jātaka genre is based on the idea that the Buddha was able to recollect all his past lives and thus could use these memories to tell a story and illustrate his teachings.[6]

For the Buddhist traditions, the jātakas illustrate the many lives, acts and spiritual practices which are required on the long path to Buddhahood.[1] They also illustrate the great qualities or perfections of the Buddha (such as generosity) and teach Buddhist moral lessons, particularly within the framework of karma and rebirth.[7] Jātaka stories have also been illustrated in Buddhist architecture throughout the Buddhist world and they continue to be an important element in popular Buddhist art.[7] Some of the earliest such illustrations can be found at Sanchi and Bharhut.

According to Naomi Appleton, Jātaka collections also may have played "an important role in the formation and communication of ideas about buddhahood, karma and merit, and the place of the Buddha in relation to other buddhas and bodhisattvas."[7] According to the traditional view found in the Pali Jātakanidana, a prologue to the stories, Gautama made a vow to become a Buddha in the future, in front past Buddha Dipankara. He then spent many lifetimes on the path to Buddhahood, and the stories from these lives are recorded as Jātakas.[8]

Jātakas are closely related to (and often overlap with) another genre of Buddhist narrative, the avadāna, which is a story of any karmically significant deed (whether by a bodhisattva or otherwise) and its result.[2][9] According to Naomi Appleton, some tales (such as those found in the second and fourth decade of the Avadānaśataka) can be classified as both a jātaka and an avadāna.[9]

Many East Asian men consider The Jātaka (Sanskrit for "Birth-Related" or "Birth Stories") to be very entertaining and great wisdom literature!

Jataka 546: The Mahā-Ummagga-jātaka

My personal favorite is Jataka 546: The Mahā-Ummagga-jātaka!

“King Brahmadatta of Pañcāla,” etc. The Teacher, while dwelling at Jetavana, told this about the perfection of knowledge. One day the Brethren sat in the Hall of Truth and described the Buddha’s perfection of knowledge: “Brethren, the omniscient Buddha whose wisdom is vast, ready, swift, sharp, crushing heretical doctrines, after having converted, by the power of his own knowledge, the Brahmins Kūṭadanta and the rest, the ascetics Sabhiya and the rest, the thieves Aṅgulimāla etc., the yakkhas Āḷavaka etc., the gods Sakka and the rest, and the Brahmins Baka etc., made them humble, and ordained a vast multitude as ascetics and established them in the fruition of the paths of sanctification.” The Teacher came up and asked what they were discoursing about, and when they told him, he replied, [330] “Not now only is the Buddha omniscient,—in past time also, before his knowledge was fully mature, he was full of all wisdom, as he went about for the sake of wisdom and knowledge,” and then he told a story of the past.

In days gone by, a king named Vedeha ruled in Mithilā, and he had four sages who instructed him in the law, named Senaka, Pukkusa, Kāvinda, and Devinda. Now when the Bodhisatta was conceived in his mother’s womb the king saw at dawn the following dream: four columns of fire blazed up in the four corners of the royal court as high as the great wall, and in the midst of them rose a flame of the size of a fire-fly, and at that moment it suddenly exceeded the four columns of fire and rose up as high as the Brahma world and illumined the whole world; even a grain of mustard-seed lying on the ground is distinctly seen. The world of men with the world of gods worshipped it with garlands and incense; a vast multitude passed through this flame but not even a hair of their skin was singed. The king when he saw this vision started up in terror and sat pondering what was going to happen, and waited for the dawn. The four wise men also when they came in the morning asked him whether he had slept well. “How could I sleep well,” he replied, “when I have seen such a dream” Then Pandit Senaka replied, “Fear not, O king, it is an auspicious dream, thou wilt be prosperous,” and when he was asked to explain, he went on, “O king, a fifth sage will be born who will surpass us four; we four are like the four columns of fire, but in the midst of us there will arise as it were a fifth column of fire, one who is unparalleled and fills a post which is unequalled in the world of gods or of men.” “Where is he at this moment?” “O king, he will either assume a body or come out of his mother’s womb”; thus did he by his science what he had seen by his divine eye and the king from that time forward remembered his words. Now at the four gates of Mithilā there were four market towns, called the East town, the South town, the West town, and the North town[2]; [331] and in the East town there dwelt a certain rich man named Sirivaḍḍhaka, and his wife was named Sumanādevī. Now on that day when the king saw the vision, the Great Being went from the heaven of the Thirty-three and was conceived in her womb; and a thousand other sons of the gods went from that heaven and were conceived in the families of various wealthy merchants in that village, and at the end of the tenth month the lady Sumanā brought forth a child of the colour of gold. Now at that moment Sakka, as he looked over the world of mankind, beheld the Great Being’s birth; and saying to himself that he ought to make known in the world of gods and men that this Buddha-shoot had sprung into being, he came up in a visible form as the child was being born and placed a piece of a medicinal herb in its hand, and then returned to his own dwelling. The Great Being seized it firmly in his closed hand; and as he came from his mother’s womb she did not feel the slightest pain, but he passed out as easily as water from a sacred water-pot. When his mother saw the piece of the medicinal herb in his hand, she said to him, “My child, what is this which you have got?” He replied, “It is a medicinal plant, mother,” and he placed it in her hand and told her to take it and give it to all who are afflicted with any sickness. Full of joy she told it to the merchant Sirivaḍḍhaka, who had suffered for seven years from a pain in his head. Full of joy he said to himself, “This child came out of his mother’s womb holding a medicinal plant and as soon as he was born he talked with his mother; a medicine given by a being of such surpassing merit must possess great efficacy”; so he rubbed it on a grindstone and smeared a little of it on his forehead, and the pain in his head which had lasted seven years passed away at once like water from a lotus leaf. Transported with joy he exclaimed, “This is a medicine of marvellous efficacy ”; the news spread on every side that the Great Being had been born with a medicine in his hand, and all who were sick crowded to the merchant’s house and begged for the medicine. They gave a little to all who came, having rubbed some of it on a grindstone and mixed it with water, and as soon as the affected body was touched with the divine medicine all diseases were cured, and the delighted patients went away proclaiming the marvellous virtues of the medicine in the house of the merchant Sirivaḍḍhaka. [332] On the day of naming the child the merchant thought to himself, “My child need not be called after one of his ancestors; let him bear the name of the medicine,” so he gave him the name Osadha Kumāra. Then he thought again, “My son possesses great merit, he will not be born alone, many other children will be born at the same time”; so hearing from his inquiries that thousands of other boys were born with him, he sent them all nurses and gave them clothes, and resolving that they should be his son’s attendants he celebrated a festival for them with the Great Being and adorned the boys and brought them every day to wait upon him. The Great Being grew up playing with them, and when he was seven years old he was as beautiful as a golden statue. As he was playing with them in the village some elephants and other animals passed by and disturbed their games, and sometimes the children were distressed by the rain and the heat. Now one day as they played, an unseasonable rainstorm came on, and when the Great Being who was as strong as an elephant saw it, he ran into a house, and as the other children ran after him they fell over one another’s feet and bruised their knees and other limbs. Then he thought to himself, “A hall for play ought to be built here, we will not play in this way,” and he said to the boys, “Let us build a hall here where we can stand, sit, or lie in time of wind, hot sunshine, or rain,—let each one of you bring his piece of money.” The thousand boys all did so and the Great Being sent for a master-carpenter and gave him the money, telling him to build a hall in that place. He took the money, and levelled the ground and cut posts and spread out the measuring line, but he did not grasp the Great Being’s idea; so he told the carpenter how he was to stretch out his line so as to do it properly. He replied, “I have stretched it out according to my practical experience, I cannot do it in any other way.” “If you do not know even so much as this how can you take our money and build a hall? Take the line, I will measure and shew you,” so he made him take the line and himself drew out the plan, and it was done as if Vissakamma had done it. [333] Then he said to the carpenter, “Will you be able to draw out the plan in this way?” “I shall not be able, Sir.” “Will you be able to do it by my instructions?” “I shall be able, Sir.” Then the Great Being so arranged the hall that there was in one part a place for ordinary strangers, in another a lodging for the destitute, in another a place for the lying-in of destitute women, in another a lodging for stranger Buddhist priests and Brahmins, in another a lodging for other sorts of men, in another a place where foreign merchants should stow their goods, and all these apartments had doors opening outside. There also he had a public place erected for sports, and a court of justice, and a hall for religious assemblies. When the work was completed he summoned painters, and having himself examined them set them to work at painting beautiful pictures, so that the hall became like Sakka’s heavenly palace Sudhammā. Still he thought that the palace was not yet complete, “I must have a tank constructed as well,”—so he ordered the ground to be dug for an architect and having discussed it with him and given him money he made him construct a tank with a thousand bends in the bank and a hundred bathing ghāts. The water was covered with the five kinds of lotuses and was as beautiful as the lake in the heavenly garden Nandana. On its bank he planted various trees and had a park made like Nandana. And near this hall he established a public distribution of alms to holy men whether Buddhists or Brahmins, and for strangers and for people from the neighbouring villages.

These actions of his were blazed abroad everywhere and crowds gathered to the place, and the Great Being used to sit in the hall and discuss the right and the wrong of the good or evil circumstances of all the petitioners who resorted there and gave his judgment on each, and it became like the happy time when a Buddha makes his appearance in the world.

Now at that time, when seven years had expired, King Vedeha remembered how the four sages had said that a fifth sage should be born who would surpass them in wisdom, and he said to himself, “Where is he now?” and he sent out his four councillors by the four gates of the city, bidding them to find out where he was. When they went out by the other three gates they saw no sign of the Great Being, but when they went out by the eastern gate they saw the hall and its various buildings and they felt sure at once that only a wise man could have built this palace or caused it to be built, [334] and they asked the people, “What architect built this hall?” They replied, “This palace was not built by any architect by his own power, but by the direction of Mahosadha Pandit, the son of the merchant Sirivaḍḍha.” “How old is he?” “He has just completed his seventh year.” The councillor reckoned up all the events from the day on which the king saw the dream and he said to himself, “This being fulfils the king’s dream,” and he sent a messenger with this message to the king: “Mahosadha, the son of the merchant Sirivaḍḍha in the East market town, who is now seven years old, has caused such a hall and tank and park to be made,—shall I bring him into thy presence or not?” When the king heard this he was highly delighted and sent for Senaka, and after relating the account he asked him whether he should send for this sage. But he, being envious of the title, replied, “O king, a man is not to be called a sage merely because he has caused halls and such things to be made; anyone can cause these things to be made, this is but a little matter.” When the king heard his words he said to himself, “There must be some secret reason for all this,” and was silent. Then he sent back the messenger with a command that the councillor should remain for a time in the place and carefully examine the sage. The councillor remained there and carefully investigated the sage’s actions, and this is the series of the tests or cases of examination[3]:

- “The piece of meat[4].” One day when the Great Being was going to the play-hall, a hawk carried off a piece of flesh from the slab of a slaughterhouse and flew up into the air; some lads, seeing it, determined to make him drop it and pursued him. The hawk flew in different directions, and they, looking up, followed behind and wearied themselves, flinging stones and other missiles and stumbling over one another. Then the sage said to them, “I will make him drop it,” and they begged him to do so. He told them to look; and then himself with looking up he ran with the swiftness of the wind and trod upon the hawk’s shadow and then clapping his hands uttered a loud shout. By his energy that shout seemed to pierce the bird’s belly through and through and in its terror he dropped the flesh; and the Great Being, knowing by watching the shadow that it was dropped, [335] caught it in the air before it reached the ground. The people seeing the marvel, made a great noise, shouting and clapping their hands. The minister, hearing of it, sent an account to the king telling him how the sage had by this means made the bird drop the flesh. The king, when he heard of it, asked Senaka whether he should summon him to the court. Senaka reflected, “From the time of his coming I shall lose all my glory and the king will forget my existence,—I must not let him bring him here”; so in envy he said, “He is not a sage for such an action as this, this is only a small matter”; and the king being impartial, sent word that the minister should test him further where he was.

- “The cattle[5].”A certain man who dwelt in the village of Yavamajjhaka bought some cattle from another village and brought them home. The next day he took them to a field of grass to graze and rode on the back of one of the cattle. Being tired he got down and sat on the ground and fell asleep, and meanwhile a thief came and carried off the cattle. When he woke he saw not his cattle, but as he gazed on every side he beheld the thief running away. Jumping up he shouted, “Where are you taking my cattle?” “They are my cattle, and I am carrying them to the place which I wish.” A great crowd collected as they heard the dispute. When the sage heard the noise as they passed by the door of the hall, he sent for them both. When he saw their behaviour he at once knew which was the thief and which the real owner. But though he felt sure, he asked them what they were quarrelling about. The owner said, “I bought these cattle from a certain person in such a village, and I brought them home and put them in a field of grass. This thief saw that I was not watching and came and carried them off. Looking in all directions I caught sight of him and pursued and caught him. The people of such a village know that I bought the cattle and took them.” The thief replied, “This man speaks falsely, they were born in my house.” The sage said, “I will decide your case fairly; will you abide by my decision?” and they promised so to abide. Then thinking to himself that he must win the hearts of the people he first asked the thief, “What have you fed these cattle with, and what have you given them to drink?” “They have drunk rice gruel and have been fed on sesame flour and kidney beans.” Then he asked the real owner, who said, “My lord, how could a poor man like me get rice gruel and the rest? I fed them on grass.” The pandit caused an assembly to be brought together and ordered panic seeds to be brought and ground in a mortar and moistened with water and given to the cattle, and they forthwith vomited only grass. He shewed this to the assembly, and then asked the thief, “Art thou the thief or not?” He confessed that he was the thief. He said to him, “Then do not commit such a sin henceforth.” But the Bodhisatta’s attendants carried the man away and cut off his hands and feet and made him helpless. Then the sage addressed him with words of good counsel, “This suffering has come upon thee only in this present life, but in the future life thou wilt suffer great torment in the different hells, therefore henceforth abandon such practices”; he taught him the five commandments. The minister sent an account of the incident to the king, who asked Senaka, but he advised him to wait, “It is only an affair about cattle and anybody could decide it.” The king, being impartial, sent the same command. (This is to be understood in all the subsequent cases,—we shall give each in order according to the list.)

- “The necklace of thread[6].” A certain poor woman had tied together several threads of different colours and made them into a necklace, which she took off from her neck and placed on her clothes as she went down to bathe in a tank which the pandit had caused to be made. A young woman who saw this conceived a longing for it, took it up and said to her, “Mother, this is a very beautiful necklace, how much did it cost to make? [336] I will make such a one for myself. May I put it on my own neck and ascertain its size?” The other gave her leave, and she put it on her neck and ran off. The elder woman seeing it came quickly out of the water, and putting on her clothes ran after her and seized hold of her dress, crying, “You are running away with a; necklace which I made.”

The other replied, “I am not taking anything of yours, it is the necklace which I wear on my neck”; and a great crowd collected as they heard this. The sage, while he played with the boys, heard them quarrelling as they passed by the door of the hall and asked what the noise was about. When he heard the cause of the quarrel he sent for them both, and having known at once by her countenance which was the thief, he asked them whether they would abide by his decision. On their both agreeing to do so, he asked the thief, “What scent do you use for this necklace?” She replied, “I always use sabbasaṃhhāraka[7] to scent it with.” Then he asked the other, who replied, “How shall a poor woman like me get sabbasaṃhāraka? I always scent it with perfume made of piyaṅgu flowers.” Then the sage had a vessel of water brought and put the necklace in it. Then he sent for a perfume-seller and told him to smell the vessel and find out what it smelt of. He directly recognised the smell of the piyaṅgu flower, and quoted the stanza which has been already given in the first book[8]:

"No omnigatherum it is; only the kaṅgu smells;

Yon wicked woman told a lie; the truth the gammer tells."

The Great Being told the bystanders all the circumstances and asked each of them respectively, “Art thou the thief? Art thou not the thief?” and made the guilty one confess, and from that time his wisdom became known to the people.

- “The cotton thread.” A certain woman who used to watch cotton fields was watching one day and she took some clean cotton and spun some fine thread and made it into a ball and placed it in her lap. As she went home she thought to herself, “I will bathe in the great sage’s tank,” so she placed the ball on her dress and went down into the tank to bathe. Another woman saw it, and conceiving a longing for it took it up, saying, “This is a beautiful ball of thread; pray did you make it yourself?” So she lightly snapped her fingers and put it in her lap as if to examine it more closely, and walked off with it. (This is to be told at full as before.) The sage asked the thief, “When you made the ball what did you put inside[9]?” She replied, “A cotton seed.” Then he asked the other, and she replied, “A timbaru seed.” When the crowd had heard what each said, he untwisted the ball of cotton and found a timbaru seed inside and forced the thief to confess her guilt. The great multitude were highly pleased and shouted their applause at the way in which the case had been decided.

- “The son.” A certain woman took her son and went down to the sage’s tank to wash her face. After she had bathed her son she laid him in her dress and having washed her own face went to bathe. At that moment a female goblin saw the child and wished to eat it, so she took hold of the dress and said, “My friend, this is a fine child, is he your son?” Then she asked if she might give him suck, and on obtaining the mother’s consent, she took him and played with him for a while and then tried to run off with him. The other ran after her and seized hold of her, shouting, “Whither are you carrying my child?” The goblin replied, “Why do you touch the child? he is mine.” As they wrangled they passed by the door of the hall, and the sage, hearing the noise, sent for them and asked what was the matter. When he heard the story, [337] although he knew at once by her red unwinking eyes that one of them was a goblin, he asked them whether they would abide by his decision. On their promising to do so, he drew a line and laid the child in the middle of the line and bade the goblin seize the child by the hands and the mother by the feet. Then he said to them, “Lay hold of it and pull; the child is hers who can pull it over.” They both pulled, and the child, being pained while it was pulled, uttered a loud cry. Then the mother, with a heart which seemed ready to burst, let the child go and stood weeping. The sage asked the multitude, “Is it the heart of the mother which is tender towards the child or the heart of her who is not the mother?” They answered, “The mother’s heart.” “Is she the mother who kept hold of the child or she who let it go?” They replied, “She who let it go.” “Do you know who she is who stole the child?” “We do not know, O sage.” “She is a goblin,—she seized it in order to eat it.” When they asked how he knew that he replied, “I knew her by her unwinking and red eyes and by her casting no shadow and by her fearlessness and want of mercy.” Then he asked her what she was, and she confessed that she was a goblin. “Why did you seize the child?” “To eat it.” “You blind fool,” he said, “you committed sin in old time and so were born as a goblin; and now you still go on committing sin, blind fool that you are.” Then he exhorted her and established her in the five precepts and sent her away; and the mother blessed him, and saying, “May’st thou live long, my lord,” took her son and went her way.

In East Asia, it was translated under the title Mahosadha Pandit, The Clever Boy.

The sight of a 7-year-old boy, Mahosadha, solving difficult problems that even adults could not solve was a surprise to East Asians.

Mahosadha became the king's advisor by wisely resolving crimes and conflicts and confrontations between people in the world.

By reading Mahosadha, I was able to learn ways and wisdom to distinguish and control the good and evil committed by people in the world!

From ancient times to the present, East Asians have been able to understand and learn about the wisdom and virtue of the people of the Indian subcontinent by reading The Jātaka (Sanskrit for "Birth-Related" or "Birth Stories").

The Jātaka (Sanskrit for "Birth-Related" or "Birth Stories") played a particularly important role in the spread of Indian Buddhism to East Asia!

I wonder if my dear brother Hassan has ever read The Jātaka (Sanskrit for "Birth-Related" or "Birth Stories")!😄

I believe that the Kamasutra symbolizes the erotic appeal of the women of the Indian subcontinent, and The Jātaka (Sanskrit for "Birth-Related" or "Birth Stories") symbolizes the wisdom and virtue of the men of the Indian subcontinent!

The Jātaka (Sanskrit for "Birth-Related" or "Birth Stories") is considered a great Indian literature that should be read by the rulers of East Asia!

It is an Indian Buddhist teaching that kings should rule the people with wisdom, patience, and virtue, not force.

The Indian subcontinent I perceive is this huge, sexually attractive and gentle woman!😄