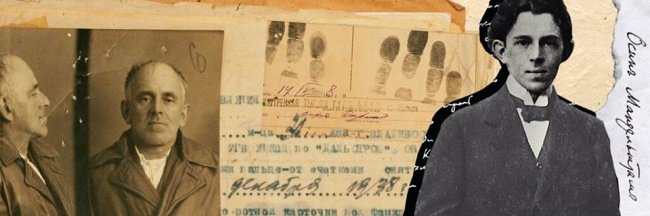

El 27 de diciembre de 1938 fallecía en un campo de concentración en Siberia uno de los más importantes poetas rusos, Ósip Mandelstam, que había sido condenado a cinco años de prisión por el dictador soviético Iosef Stalin, por atreverse a ejercer su libertad creativa en crítica a aquel nefasto personaje histórico y a su oprobioso régimen. El poema, que fuera escrito en 1933, se le conoce como "Epigrama contra Stalin". Mandelstam fue arrestado en 1934. En este enlace pueden leer dos versiones en español del poema en cuestión.

El poeta venezolano Rafael Cadenas (Premio Cervantes 2023) le dedicó, en su libro Gestiones (1992), un poema que lleva por título el nombre del sacrificado poeta ruso, poema que reproduzco a continuación:

Mandelstam

Vivo

¿a quién debo este honor?Mi alma vacila. Dante me acompaña

a través de la noche soviética.Yo vago entre las ruinas

de la Hélade.No puedo huir.

Esconde

los poemas, Nadezda.¿Cómo pudiste, César,

destruir

nuestra vivacidad?He abandonado toda esperanza

a la entrada del campo.El único que habla ruso

no podía olvidar.

Un dios perdona,

un semidiós no.Los gritos

se pierden en la vastedad de mi país.

En uno de mis estudios sobre la obra del poeta venezolano, escribí un texto de comentario de este poema, que dejo seguidamente para su amable lectura.

“Mandelstam” constituye un texto poético de gran complejidad, fuerza y crudeza, que asume –de ahí su título– la voz del poeta ruso Ósip Mandelstam (1891-1938), quien vivió y sufrió la revolución soviética, hasta ser confinado, por su disidencia, en un campo de concentración en Siberia durante el régimen stalinista, a consecuencia de lo cual murió. La crítica lo considera como el principal representante, al lado de Anna Ajmátova, del movimiento acmeísta, tendencia que se caracterizó por proponer la precisión y la concisión en la poesía. Fue autor de dos relevantes libros de poemas: La piedra, de 1913, y Tristia, de 1922.

El poema está poblado de referencias históricas, tanto culturales como políticas, e incluye algunas citas textuales del autor ruso. Así, por ejemplo, empieza con dos versos suyos: “Vivo / ¿a quién debo este honor?”, los cuales nos aportan de entrada el tono que reinará en todo el poema. La desesperanza y la conciencia de gratitud y dolor fluyen paralelamente por esta habla de discurrir entrecortado, fragmentado, como imágenes en desvarío de un alma turbada. La frase a continuación lo explica: “Mi alma vacila”. Es la fluctuación y el temblor, la zozobra de una interioridad sometida a la oscuridad en una travesía abismal, en la que la única compañía es Dante. Leemos: “Dante me acompaña / a través de la noche soviética”. El alma abatida del poeta sólo puede asirse al arquetipo del viaje y el descenso representado por Dante, imagen ejemplar para el sostenimiento. A propósito del descenso al abismo (o a los ‘ínferos’, como le gusta decir a María Zambrano), símbolo arquetipal de purga o prueba en el mito, las religiones y el arte (tal lo indica Cirlot en su Diccionario de símbolos), es apropiado indicar el uso que de él ha hecho Cadenas en su obra para simbolizar el necesario acrisolamiento por el cual debe atravesar la experiencia humana y poética en particular. Podemos ver en Dichos: “No se puede escribir cosa valedera sin haber estado en el infierno”.

Con las referencias simbólicas señaladas, el yo del poema “Mandelstam” interpreta su itinerario en este ‘corazón de las tinieblas’. Su acendrada cultura clásica es el interpretante de este cerrado mundo, explicación de la referencia a Grecia y a su destrucción en manos del poder romano: “Yo vago entre las ruinas / de la Hélade”, “¿Cómo pudiste, César, / destruir / nuestra vivacidad?”. La comparación tácita con el destino histórico vivido por la Grecia clásica habla, también, de la riqueza (“vivacidad”) anterior y de la situación de devastación actual (“las ruinas”) de su país, a manos del “César” contemporáneo, Stalin o poder soviético.

En medio de este discurrir vacilante, dos segmentos nos conmueven por el sufrimiento y el desaliento que recogen. El primero: “No puedo huir. / Esconde / los poemas, Nadezda”. No hay posibilidad real de fuga, ¿la poesía lo será? Es sugestivamente ambiguo el llamado a la esposa: “Esconde los poemas...” Podríamos ver en esta frase la aprensión por la persecución a que se le ha sometido y el deseo de salvar lo único que puede trascender como reducto de libertad (“Libertad bajo palabra”, diría Octavio Paz), pero también el escepticismo ante el sentido de la poesía (“Para qué poetas en tiempos de penuria”, se había preguntado Hölderlin). En el segundo fragmento vamos a sentir crudamente ese transido escepticismo o pesimismo: “He abandonado toda esperanza / a la entrada del campo”. El umbral del infierno, la entrada al campo de concentración.

Sólo quedan dos estrofas. La penúltima no es de fácil interpretación, pues requeriría poseer cierta información especializada: “El único que habla ruso / no podía olvidar. / Un dios perdona, / un semidiós no”. La frase inicial, que creemos cita textual de Mandelstam (de allí el subrayado en el original), podría resultar problemática. Las referencias extraliterarias (históricas) nos conducen a pensar que alude a Stalin , quien era el gobernante autocrático de la Unión Soviética para el momento y, por tanto, responsable de la prisión del poeta. Al resaltar esta frase, Cadenas no sólo registra la ajena procedencia de lo dicho y lo intensifica semánticamente, sino también nos prepara para reconocer el autoritarismo y ultraje del poder (“no podía olvidar”), lo que se completa en las dos líneas siguientes. La mediocridad del poder es clara entonces: el perdón –la piedad, la compasión– es ajena a la autoridad despótica que, si bien ha sido endiosada, sólo llega a ser un falso y mezquino personaje encumbrado.

La última estrofa cierra con una imagen grave y desoladora: “Los gritos / se pierden en la vastedad de mi país”. Declaración de la vida en el dolor, los gritos del poeta y de los demás se extravían en la inmensidad sorda e impotente.

Referencias | References:

Cadenas, Rafael (1992). Gestiones. Caracas, Venezuela: Edit. Pomaire.

https://www.poeticous.com/rafael-cadenas/mandelstam?locale=es

https://www.poesi.as/rfc9204180uk.htm

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%93sip_Mandelstam

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Osip_Mandelstam

https://www.zendalibros.com/5-poemas-osip-mandelstam/

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/osip-mandelstam

https://www.elnacional.com/entretenimiento/dos-versiones-del-poema-osip-mandelstam-sobre-stalin_211356/

Click here to read in english

Osip Mandelstam, the Russian poet condemned by Stalinism

On December 27, 1938, one of the most important Russian poets, Ósip Mandelstam, died in a concentration camp in Siberia. He had been sentenced to five years in prison by the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin for daring to exercise his creative freedom in criticism of that nefarious historical figure and his disgraceful regime. The poem, which was written in 1933, is known as "Epigram against Stalin. Mandelstam was arrested in 1934. In this link you can read the versions in English of the poem in question.

The Venezuelan poet Rafael Cadenas (Cervantes Prize 2023) dedicated to him, in his book Gestiones (1992), a poem that bears the name of the sacrificed Russian poet, a poem that I reproduce below:

Mandelstam

I'm alive.

To whom do I owe this honour?

My soul staggers. Dante accompanies me

through the Soviet night.

I wander through the ruins

of Hellas.

I can't flee.

Hide

the poems, Nadezhda.

Caesar, how could you

destroy

our liveliness?

I have abandoned all hope

at the entrance to the camp.

The only man who speaks Russian

couldn’t forget.

A god forgives,

a demigod does not.

The shouts

are lost in the vastness of my country.

In one of my studies on the work of the Venezuelan poet, I wrote a commentary text on this poem, which I leave below for your kind reading.

“Mandelstam” is a poetic text of great complexity, strength and crudeness, which assumes —hence its title— the voice of the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938), who lived and suffered the Soviet revolution, until being confined, for his dissidence, in a concentration camp in Siberia during the Stalinist regime, as a result of which he died. Critics consider him to be the main representative, alongside Anna Akhmatova, of the acmeist movement, a trend characterized by proposing precision and conciseness in poetry. He was the author of two important books of poems: The Stone, from 1913, and Tristia, from 1922.

The poem is filled with historical references, both cultural and political, and includes some textual quotes from the Russian author. Thus, for example, it begins with two of his verses: “I'm live / to whom do I owe this honor?”, which give us the tone that will reign throughout the poem. Despair and the awareness of gratitude and pain flow in parallel through this speech of broken, fragmented flow, like images in the delirium of a troubled soul. The phrase that follows explains it: “My soul wavers.” It is the fluctuation and the trembling, the anxiety of an interiority subjected to darkness in an abysmal journey, in which the only company is Dante. We read: “Dante accompanies me / through the Soviet night.” The poet’s dejected soul can only cling to the archetype of the journey and the descent represented by Dante, an exemplary image for support. Regarding the descent into the abyss (or to the ‘infernos’, as María Zambrano likes to say), an archetypal symbol of purge or test in myth, religions and art (as Cirlot indicates in his Diccionario de Símbolos), it is appropriate to indicate the use that Cadenas has made of it in his work to symbolize the necessary purification that the human and poetic experience in particular must go through. We can see in Dichos: “You cannot write anything worthwhile without having been in hell.”

With the symbolic references indicated, the “I” in the poem “Mandelstam” interprets his journey in this ‘heart of darkness’. His deep classical culture is the interpreter of this closed world, explaining the reference to Greece and its destruction at the hands of Roman power: “I wander among the ruins / of Hellas”, “How could you, Caesar, / destroy / our vivacity?” The tacit comparison with the historical destiny experienced by classical Greece also speaks of the wealth (“vivacity”) of the past and the current situation of devastation (“the ruins”) of his country, at the hands of the contemporary “Caesar”, Stalin or Soviet power.

In the midst of this hesitant discourse, two segments move us with the suffering and discouragement they capture. The first: “I cannot escape. / Hide / the poems, Nadezda.” There is no real possibility of escape, but is poetry possible? The call to his wife is suggestively ambiguous: “Hide the poems…”. In this phrase we can see the apprehension of the persecution to which he has been subjected and the desire to save the only thing that can transcend as a bastion of freedom (“Freedom on parole,” Octavio Paz would say), but also skepticism about the meaning of poetry (“What are poets for in times of hardship?” Hölderlin had asked himself). In the second fragment we are going to crudely feel this transfixed skepticism or pessimism: “I have abandoned all hope / at the entrance to the camp.” The threshold of hell, the entrance to the concentration camp.

There are only two stanzas left. The penultimate one is not easy to interpret, since it would require certain specialized information: “The only one who speaks Russian / could not forget. / A god forgives, / a demigod does not.” The initial phrase, which we believe is a direct quote from Mandelstam (hence the underlining in the original), could be problematic. The extra-literary (historical) references lead us to think that it alludes to Stalin, who was the autocratic ruler of the Soviet Union at the time and, therefore, responsible for the poet’s imprisonment. By highlighting this phrase, Cadenas not only records the foreign origin of what was said and intensifies it semantically, but also prepares us to recognize the authoritarianism and outrage of power (“he could not forget”), which is completed in the following two lines. The mediocrity of power is then clear: forgiveness – pity, compassion – is foreign to despotic authority that, although it has been deified, only becomes a false and petty exalted character. The last stanza closes with a serious and desolate image: “The screams / are lost in the vastness of my country.” A declaration of life in pain, the screams of the poet and others are lost in the deaf and impotent immensity.

Esta publicación ha recibido el voto de Literatos, la comunidad de literatura en español en Hive y ha sido compartido en el blog de nuestra cuenta.

¿Quieres contribuir a engrandecer este proyecto? ¡Haz clic aquí y entérate cómo!

When a dictator is in power, those that attempt to criticise their actions end up paying with their lives. We see this repeated all through history, sad as it is.

That's right, unfortunately. It would be desirable if there were no authoritarian powers and freedom of expression existed all over the world. Thank you for your visit and comment, @ngwinndave.

@commentrewarder

The commentrewarder command is used to reward the comments that are left on your post, and it rewards you with that 5% if you do not vote on the comments you will not receive anything and you will lose them, greetings

Thank you for your clarification, @gladiadorr.

@josemalavem, I'm refunding 0.162 HIVE and 0.057 HBD, because there are no comments to reward.