Imagine this: Alex, a 29-year-old fitness enthusiast, walks into a routine health checkup. His biceps bulge under his shirt, his shoulders are broad, and his abs are well-defined. As a dedicated athlete who spends hours in the gym, Alex prides himself on his physical health. But when his doctor calculates his Body Mass Index (BMI), she frowns slightly. "You’re classified as overweight," she says.

Alex is confused. Overweight? He’s in peak physical condition! How could this simple calculation—a number derived from his weight and height—paint such a distorted picture of his health?

Now, picture someone else: Maria, a 65-year-old retiree who rarely exercises. She’s petite, with a slight frame, and has always been told her weight is "perfectly normal." Yet, beneath the surface, her body fat percentage is higher than ideal, and her muscle mass has significantly decreased over the years. Her BMI? Perfectly within the "normal" range.

These two scenarios highlight the limitations of BMI, a tool that has been a cornerstone of health assessments. Here is why it might not be as accurate or useful as you think.

The History of BMI

In the early 19th century, Adolphe Quetelet, a Belgian mathematician, statistician, and sociologist, sought to define the "average man." Between 1830 and 1850, he developed what he called the Quetelet Index—a formula that divided a person’s weight in kilograms by their height in meters squared. Quetelet’s goal was not medical; instead, he was searching for a way to describe population averages and determine the socially "ideal" human form.

Quetelet’s data came primarily from Scottish Highland soldiers and the French Gendarmerie, a predominantly European male demographic. It was never meant to be applied to individuals of different genders, ethnicities, or body types. Yet, more than a century later, this formula would gain a new name and a broader role: the Body Mass Index (BMI).

How BMI Became a Global Health Tool

In 1972, Ancel Keys and colleagues published a paper introducing the modern term "Body Mass Index." They argued that BMI, while imperfect, was as good as any other metric for estimating relative obesity in populations. This led to BMI becoming widely adopted as a health screening tool.

Its appeal was its simplicity: BMI requires only two numbers—height and weight—and produces a single figure that places people into categories like underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese. Public health organizations embraced it, and soon it became a standard in health assessments worldwide.

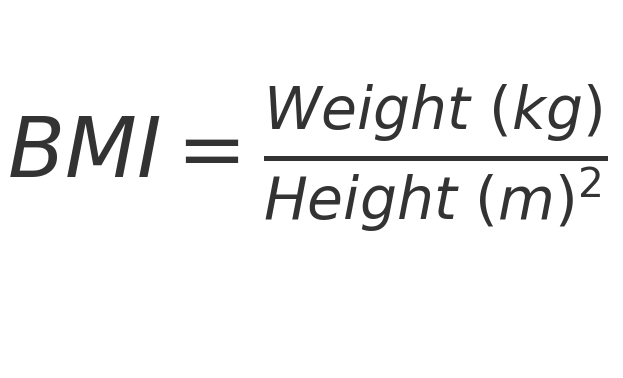

What Exactly Is BMI?

This calculation places individuals into categories:

- Underweight: BMI < 18.5

- Normal weight: BMI 18.5–24.9

- Overweight: BMI 25–29.9

- Obese: BMI ≥ 30

Why Is BMI So Popular?

BMI is popular because it is simple. It only requires two easily measured factors—weight and height—making it a quick and practical tool for large-scale studies and public health initiatives. Health professionals often use it as a preliminary screening method to identify individuals who might be at risk for weight-related health issues.

But while BMI is simple, it’s also flawed.

How BMI Can Be Misleading

1. BMI Does Not Differentiate Between Muscle and Fat

One of the most glaring issues with BMI is that it doesn’t distinguish between muscle mass and fat mass.

Muscle vs. Fat Density

Muscle is denser than fat. Muscle tissue has a density of about 1.1 grams per cubic centimeter (g/cm³), while fat has a density of approximately 0.9 g/cm³. This means that muscle tissue is about 22% denser than fat.

Composition Differences

- Fat: Adipose tissue is composed of loosely packed cells designed to store energy as triglycerides. It has less water and is less compact, resulting in a lower density.

- Muscle: Muscle is made up of tightly packed fibers rich in proteins like actin and myosin and contains significant water content, making it heavier for its size.

Take Alex, for example. As a muscular athlete, his higher muscle mass results in a higher weight, pushing his BMI into the "overweight" range, even though his body fat percentage is exceptionally low.

Conversely, Maria’s situation demonstrates the opposite. With age-related muscle loss and increased fat stores, her BMI falls within the "normal" range, masking potential health risks associated with her body composition.

2. BMI Ignores Fat Distribution

Where your body stores fat matters. Research shows that visceral fat—fat stored around your internal organs—poses a greater risk to your health than subcutaneous fat stored just under the skin. Two people with the same BMI can have vastly different fat distribution, leading to different health risks that BMI alone cannot capture.

The Takeaway

BMI is a blunt instrument. While it can provide a quick snapshot of weight-related risk, it often oversimplifies the complexities of individual health.

... to be continued

I remember reading a long time ago that the body mass index was a calculation that did not really serve to estimate body fat or overweight.

In that sense, a friend told me that if an index was wanted with only a couple of body measures, it was better to work with the waist-reef index, for the calculation of risk.

But in all cases, body fat estimates and adequate weight for health are things that should be done by professionals, and with something better than a simple index.

After all, the Quetelet index was to calculate the ‘corpulence’, understanding it as the projection in a plane of the volume of a three-dimensional body. Unless that's what I remember.

Thanks for your message. You see right. Using a waist to height ratio has been found to be a lot more useful than the BMI in estimating metabolic health.