Opponents of Spain's newly elected Prime minister, Pedro Sanchez, have, in the last month or so accused him of undermining the rule of law, being a traitor and carrying out a coup. That's all because of his deal with Catalan separatists that secured his reappointment as prime minister following an election in July that ended with no outright winner. So with protests continuing in Spain, I decided that we should take a look at this controversial amnesty deal and the opposition to it, as well as explaining why harder times are lying ahead for Pedro Sanchez's government.

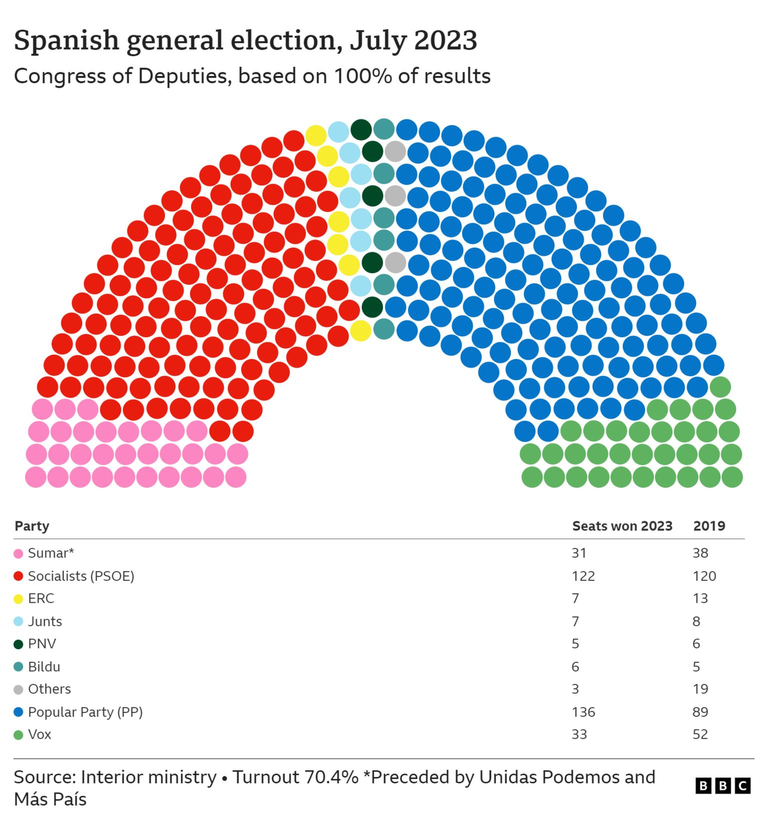

For some context, we need to go all the way back to the summer of this year when Spain held a snap general election. This election was called around five months early by Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez, after his Socialist Workers Party and its leftist coalition partner suffered a bruising defeat at the local and regional elections in May. The subsequent election in July had broadly been expected to bring a right wing coalition into power, comprising of the People's Party. That's the main conservative opposition party and the far right Vox as their junior partner. Now, the People's Party did indeed come first, but the election effectively resulted in parliamentary deadlock between a right wing bloc and the left wing regionalist bloc, with both falling short of a parliamentary majority. Crucially, though, the Pro-catalan Independence Junts party found itself in the position of kingmaker, with its seven seats crucial for either bloc to secure a majority. At the end of September, the People's Party had the first attempt at forming a government, but the party's leader failed to get the backing of the Chamber of Deputies, not surprising, given that they would have needed the support of various regionalist and separatist parties that are deeply opposed to Vox, who would have also gone into government with the People's Party.

Following this defeat, the mandate was then handed over to Pedro Sanchez as the leader of the second largest party in parliament. But if he wanted his left wing minority coalition to continue, then he'd need the backing of various smaller parties, including the Junts, in order to become prime minister. However, months of negotiations had proved fruitful by this point, with Sanchez securing the necessary support from regional parties in Catalonia, the Basque Country, Galicia and the Canary Islands. Controversially, though, in order to secure the backing of the Junts and the Republican Left of Catalonia aka the ERC, which is another Pro-catalan independence party, Sanchez, among other things, agreed to pass legislation providing for a blanket amnesty for those prosecuted for their involvement in the failed push for independence. But crucially, what does this amnesty bill actually do? Well, the blanket amnesty would cancel penal, administrative and financial penalties imposed on more than 300 people for their involvement in the Catalan separatist movement between January 2012 and November 2023, which obviously includes the unsuccessful 2017 independence referendum, which was declared illegal and unconstitutional. Additionally, the amnesty is expected to also benefit more than 70 police officers who were prosecuted for their actions during the clashes with protesters. Given that it's a blanket amnesty, the bill doesn't set out a list of individuals who would benefit, but likely beneficiaries would include the likes of Carles Puigdemont, the separatist leader who fled to and remains in Belgium following the 2017 referendum in order to avoid charges of rebellion, sedition and more.

It's worth pointing out, though, that the amnesty bill has been introduced to, but not passed through the Spanish Parliament. Now it will pass through the lower house, but will likely be delayed in the Senate, and even when it is approved by the Parliament, it will undoubtedly be challenged by the courts, meaning that the success of this amnesty isn't actually guaranteed. Regardless, this deal was enough to secure Pedro Sanchez a secure majority in parliament for his second term, and on the 16th of November, he successfully passed the investiture vote with the support of all but three parties, allowing him to form a minority government made up of his Socialist Party and Sumar. The amnesty deal has sparked significant outrage in Spain, not just from Sanchez's right wing political opponents, but also among the wider public. Protests began even before the deal was reached, and things have only intensified recently. The most recent weekend protests last Saturday had an estimated 170,000 people marching through Madrid in opposition to the amnesty law, which was decried by opposition politicians and a number of judicial associations for undermining the judiciary and the rule of law. In fact, the leader of Vox has gone as far as describing it as a coup d'état in capital letters. The People's Party have also urged the EU to intervene, claiming that. The amnesty law demands the kind of response that the EU has given to rule of law concerns in places like Poland and Hungary. Conservative groups in the European Parliament have also suggested that they should get a debate scheduled on Spain's democratic quality.

Now, Pedro Sanchez and his government have obviously rejected any such claims, and instead have said that the amnesty is necessary to defuse the Catalan conflict and allow the country to move forward. And to be fair. Blanket amnesty laws are not unprecedented in Spain, for example, during Spain's transition to democracy a blanket amnesty was passed in 1977 to cover crimes committed during the dictatorship of General Franco. It's also not the first time that Sanchez has controversially extended an olive branch to Catalan separatists. In 2021, his government pardoned nine independence leaders jailed for their role in the 2017 referendum and in 2022, he requalified the crime of sedition as an aggravated public disorder. However, part of the reason that the amnesty law is so controversial is that people see it as obviously and inextricably linked to the formation of the government and Sanchez's own self-preservation. So that brings us to the question could these protests and the wider backlash to the amnesty law actually bring down Pedro Sanchez's government? Well, having defied the odds to be re-elected as prime minister, Sanchez has a fraught term ahead, but not necessarily because of the backlash to the amnesty. Sanchez is also running a minority government, so the votes of the Catalan separatist parties will likely be crucial for all future legislation, and said parties have made clear that the socialists only secured their support to make Sanchez prime minister.

As for future parliamentary support, it will be on a case by case basis and contingent on progress towards the thing set out in their agreement with Sanchez as alliance. And don't forget, the ultimate goal of parties like Junts and the ERC is a legal referendum on independence granted by the government in Madrid. So they will certainly use their parliamentary weight to push towards that. Sanchez also has a brewing crisis within his own ranks, with tensions rising inside his coalition partner Sumar, which isn't actually one party but instead an alliance of smaller leftist parties. Podemos, a party within Sumar that led the alliance's predecessor, has on occasion clashed with Sumar leadership and has been left without any ministerial portfolios in Pedro Sanchez's newly formed government, creating a further rift. So, as it turns out, forming a government may have actually been the easy part. Keeping that government together and actually getting things done may prove to now be a whole lot harder.