The past week has been hectic for inter-Korean relations. Pyongyang kicked things off by launching a spy satellite into space on Tuesday and next thing you know, South Korea suspends a 2018 no fly zone agreement with North Korea, saying they will resume surveillance flights along the border. Now, Pyongyang is threatening to fully suspend the agreement and they're even talking about live fire exercises along the demarcation line. This escalation in tension is obviously especially alarming because of North Korea's nuclear capabilities. So in this article, we're going to take a look at what the suspension of the agreement really means, how big of a deal it really is and the possibility that North Korea, under its current regime, might take aggressive measures to annex or attack its southern neighbor.

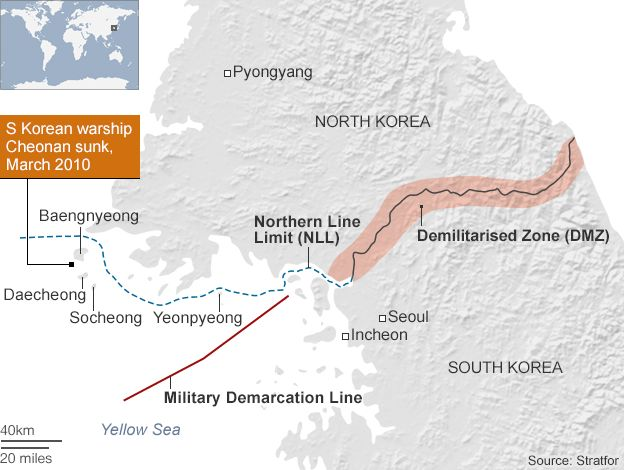

First, let's take a look at the history of inter-Korean relations. North and South Korea share a language and history, but their modern relationship has been marked by conflict and political division. After World War II, Korea was split into two, the North under Soviet control and the South under US control, and by 1948 there were two separate countries. Then in 1950, with backing from Stalin and Mao, North Korea attacked South Korea, kicking off the Korean War, which lasted for the next three years. Even though there was an armistice and ceasefire, the two countries are technically still at war because there's never been a formal peace agreement. The 1953 ceasefire established the Demilitarized Zone, or DMZ, a 160 mile long, two and a half mile wide border dividing the Korean Peninsula into two. Created by North Korea, China and the United Nations, it's the world's most fortified border, designed as a buffer to prevent further military conflicts between the two nations.

North-south relations from 1953 to today have been characterized by periods of tension and occasional diplomatic engagement, which is heavily dependent on the domestic politics of the South Korean government. Despite attempts to improve relations in the late 1980s and early 2000, like the Sunshine Policy under South Korea's Kim Dae Jung, which gave way to a series of inter-Korean summit meetings things still always find a way of going south, and tensions persist. North Korea dislikes the joint military exercises between the US and South Korea, and South Korea is regularly distressed by North Korea's frequent nuclear tests and missile launches. In 2010, the South Korean ship ROKS Cheonan was sunk near North Korea, killing 46 sailors. The Joint Civilian Military Investigation Group, or Jig, attributed the attack to a North Korean submarine, a claim denied by North Korea. Later that year, North Korea shelled Yeonpyeong Island, killing two Marines and two civilians, marking perhaps the most severe escalation in tension since the 1953 Korean War.

In 2018, however, a diplomatic breakthrough occurred, with historic summits between Kim Jong un, South Korean President Moon Jae-in, and Donald Trump. Moon, who entered office in 2017, pursued a peaceful prosperity policy advocating for dialogue and peaceful resolution between the two Koreas. In 2018, he created the No Fly Zone Agreement, which stated there will be no more war on the Korean Peninsula and thus a new era of peace has begun. To achieve this new era of peace, both countries promised to stop military exercises near the border and to refrain from any live fire practices in certain areas. They also agreed on no fly zones, removing some border guard posts and using hotlines to improve communications. Somewhat predictably, though, tensions have been simmering since, with things getting progressively worse since the start of 2023. The world got a bit of a shock when North Korea ramped up its ballistic missile tests early in the year, which was followed by Pyongyang's unveiling of a new hypersonic missile in early October. Global tensions have exacerbated inter-Korean tensions, as the North east Asian region apparently returns to its post-Cold War alignment with Russia and China getting friendlier with North Korea.

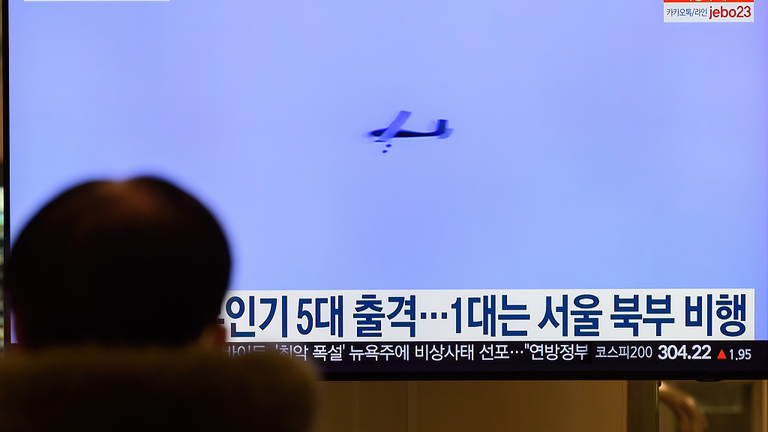

South Korea is particularly concerned about reports that North Korea is supplying munitions to Russia for its war in Ukraine, in return for Russian tech support to its nuclear and missile programs. South Korean President Yoon Suk yeol criticized the situation at the UN, noting the apparent hypocrisy in that Russia, a UN Security Council member tasked with ensuring global peace, is at war and is receiving weapons from a government blatantly violating UN rules. The ongoing crisis in the Middle East has also further stoked insecurity on the Korean Peninsula. In October, the chair of South Korea's Joint Chiefs of Staff also said that if Pyongyang was to wage war on the South in the future, there was evidence to suggest it could follow a similar pattern to a Hamas style attack across the border. Furthermore, South Korea's recently appointed defense minister suggested in early November to ditch the current agreement and use surveillance drones to keep an eye on the north, apparently inspired by what happened to Israel on October the 7th. Seoul is even building its own missile defense system. A similar structure to Israel's Iron Dome. In response, the north has been ramping up its military presence and rebuilding guard posts along the DMZ.

So what's next? How much worse can things get now that the no fly zone is a no go? And is there a possibility that North Korea will attack the South? Well, we've got to consider a few things here. The risk of escalation hinges a lot on the leadership of both governments. The current South Korean administration has adopted a tougher stance than its predecessors, emphasizing military strength and deterrence over dialogue. This tit for tat approach, a stark contrast to former President Moon's more passive stance, could increase the likelihood of further escalation similar to the 2010 island shelling and the sinking of the ROKS Cheonan ship. However, violent conflict, let alone full blown war, still looks deeply unlikely. History shows that the two Koreas have been here before, and the current saber rattling is best understood as deterrence rather than pre-invasion aggression. The US and South Korea have worked together to reduce the risk of war and keep North Korea under control for many decades, making clear that any attack on the South means game over for Kim Jong un's regime, whose primary objective is its own survival.

However, even if no one wants war without the no fly zone, accidental escalation becomes significantly more likely and the budding alliance of Russia, China and North Korea also risks disrupting the delicate geopolitical balance on the peninsula. Much like when Stalin and Mao backed North Korea in the 1950s war. On top of that, there were also now a number of other potential trigger points in the region, such as a clash over Taiwan and South China Sea disputes that could rapidly escalate into a new geopolitical crisis. And it's not unthinkable that North Korea, as an ally of China, the local superpower, would somehow get involved. All in all, while accidental escalation could happen with the violation and suspension of the no fly zone, the chances of a full blown war or annexation are still very low, and inter-Korean relations remain mostly the same as they were at the end of the Korean War.

Source of potential text plagiarism

Plagiarism is the copying & pasting of others' work without giving credit to the original author or artist. Plagiarized posts are considered fraud. Fraud is discouraged by the community.

Guide: Why and How People Abuse and Plagiarise

If you believe this comment is in error, please contact us in #appeals in Discord.