In a state televised documentary aired on October the 13th, Ethiopia's Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed argued that the Red sea was the landlocked country's natural boundary and that Ethiopia needed a port on the sea to break out of what he described as a geographic prison. Unsurprisingly, this didn't go down well with Ethiopia's Red sea neighbors Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia, not least because Abiy didn't notify them before raising the issue, but also because a few days later, Abby ominously warned that the country's lack of port access could fuel a future conflict. Just a few days after the broadcast, Ethiopia then staged a military parade in the capital, Addis Ababa and the head of the air force warned his troops to be ready for war. Later, satellite imagery detected troop movements along the Ethiopia Eritrea border, and an Ethiopian official told The Economist if port access is not achieved by other means, war is on the way. So in this article, we're going to have a look at Ethiopia's national preoccupation with port access and whether Abe, who somewhat ironically won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019, could actually start yet another war.

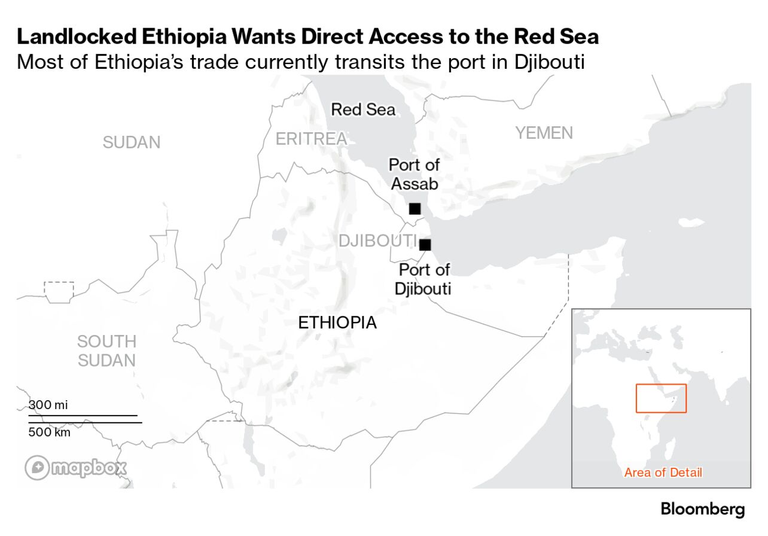

So the first thing to say here is that it isn't a new idea in Ethiopia. Ethiopia's political class has long been worried about the country's lack of port access, especially since Eritrea gained independence in 1993 and the Ethiopia Eritrea war in 1998. Before 1993 Eritrea was a federalized part of Ethiopia, which meant that Ethiopia had access to the Red sea. Ethiopia was particularly reliant on the Assab port in the south east of Eritrea, which accounted for something like 70% of all of Ethiopia's external trade. After Eritrea declared independence in 1993, Ethiopia became landlocked, but relations were originally quite friendly and Eritrea allowed Ethiopia to continue using its ports. However, the outbreak of war in 1998 over the disputed border region of Badme ruined relations, and Eritrea stopped allowing Ethiopia access to its ports. Ethiopia responded by signing a deal with Djibouti to use the Port of Djibouti, which now handles over 90% of Ethiopia's external trade with Ethiopia paying some $1.5 billion a year in port fees.

Now, this was always a suboptimal arrangement from Ethiopia's point of view both because well, it costs $1.5 billion a year and Djibouti knows that it can charge Ethiopia basically as much as it wants, but also because Ethiopia's reliance on the port of Djibouti and the main road running connecting it created a strategic vulnerability. Essentially, Ethiopia's reliance on the port of Djibouti and the A1 motorway, which runs from Djibouti through the Afar region down to Addis Ababa, means that the country is vulnerable to a blockade in the event of a conflict. If a belligerent were to cut off access to the port or even just the A1 highway, then Ethiopia would immediately be deprived of most of its imports. This became apparent during the Tigray War, when the Ethiopian government became anxious about Tigrayan rebels reaching and blockading the A1 highway, knowing the damage it could do to Ethiopia's economy and government. Anyway to reduce Ethiopia's reliance on Djibouti, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has been trying to negotiate access to other Red sea ports. His government is currently building a transport corridor to the Lamu port in Kenya, and restoring access to the Assab and Massawa ports was clearly a contributing factor in the peace deal he signed with Eritrea back in 2018.

Unfortunately, neither of these efforts have really come to fruition. The Lamu Transport Corridor is still in its early phases and has been delayed multiple times, while Ethiopia's access to Eritrea's Assab and Massawa ports has been jeopardized by the recent falling out between Abbi and Eritrea's authoritarian leader Isaias Afwerki, who's been in power since Eritrea achieved independence in 1993. Now, to understand both the Ethiopia Eritrea peace deal in 2018 and the recent falling out, you need to know a bit about Ethiopia's internal politics. Essentially, for most of Ethiopia's history, the country was run by the Tigrayan People's Liberation Front, which was unsurprisingly dominated by Tigrayans, who hail from Ethiopia's northern region of Tigray. Tigray shares a border with Eritrea, including the disputed Badme region, and Tigrayans, therefore did most of the fighting during the Ethiopia Eritrean border war, which is why the TPLF really didn't like Afewerki's Eritrea. However, when Abby came to power in 2018, he almost immediately signed a peace deal with Afwerki. This was both because, as a non Tigrayan, he wasn't as fussed about the Eritrean conflict, but also because he saw a deal with Eritrea as a good way to keep down the TPLF, who really don't like Abby.

With Eritrea on Abby's side, the Tplf in Tigray were essentially surrounded by federal forces to the south and the Eritrean army to the north. When a civil war broke out between Abiy's federal forces and the Tplf back in late 2020, the Eritrean army tacitly supported Abiy's federal forces, which is one of the reasons that Abby was able to hold on to power. However, Abby and Afwerki have fallen out recently, in part because Abby signed a peace deal with the Tplf in late 2022, which Afwerki perceived as an imperialist ploy by the West to save the Tplf, but also because Eritrea, which was basically a pariah state until very recently, has fostered closer ties with countries like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Russia and China. This means that Eritrea is no longer diplomatically dependent on Ethiopia, which has given Afwerki more room for manoeuvre on foreign policy. Anyway, this has renewed Abby's anxieties about Ethiopia's land lock, which is why he started basically threatening his neighbors in an attempt to leverage port access. So what happens next?

Well, while a war still feels unlikely, Abby has been remarkably confrontational since coming to power in 2018. Not only has he been at war with the Tplf for most of his premiership, but he's also irritated both Sudan and Egypt by building and filling the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which sits on the top of the Blue Nile and could limit downstream countries access to water. The point I am trying to make is that Abiy has been a remarkably headstrong leader, so it would be a mistake to rule conflict out, especially if he decides, as he has with the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, that port access is instrumental for Ethiopia's future development. If this were to happen, it would be yet more bad news for a region that's been beset by instability. Both Ethiopia and Eritrea have been dealing with the Tigray war and its aftermath since 2020. Sudan is currently in the midst of a civil war. Kenya has seen widespread protests over the past few months and Somalia is still well, a mess.

Russia has shown that borders can be changed by warfare. Now its back to regular human history after a period in fantasy land that borders were completely sacrosanct.

We used to see small border conflicts and border changes in a few third world countries, but the 2000s brought major border conflicts, leaving behind 50 years of ultra-peace. Structures such as the European Union aim to create a solid union structure to prevent such major border changes, but we can see that this has failed in areas outside their sphere of influence, such as 2014-Ukraine, Georgia and today Ukraine.

We are witnessing an interesting historical era, I wonder what time will show us.