If you even glance at the headlines, it can feel like Europe is souring on immigration. In just the last week, Switzerland's federal elections were won by the migrant skeptic Swiss People's Party. Interior ministers from across the EU released a statement demanding tighter immigration rules and even the usually liberal Olaf Schulz gave an interview with Der Spiegel, arguing for a more aggressive deportation system. While this renewed focus on immigration is in part a reaction to the recent events, namely a Europe wide rise in anti-Semitic offenses and Hamas based terror attacks in France and Belgium, immigration has been rising steadily up the EU's agenda for some time now. In France, Macron said last month that he wanted to significantly reduce immigration, in Italy Meloni has called for a naval blockade of the Italian coast, and warned that the EU could be overwhelmed by immigration. And in the Netherlands, Mark Rutte's government was brought down by internal disagreements over immigration. So in this article, we're going to take a look at why this migration is such a hot topic in the EU at the moment. Why the EU's current system doesn't work, and whether the EU can fix it.

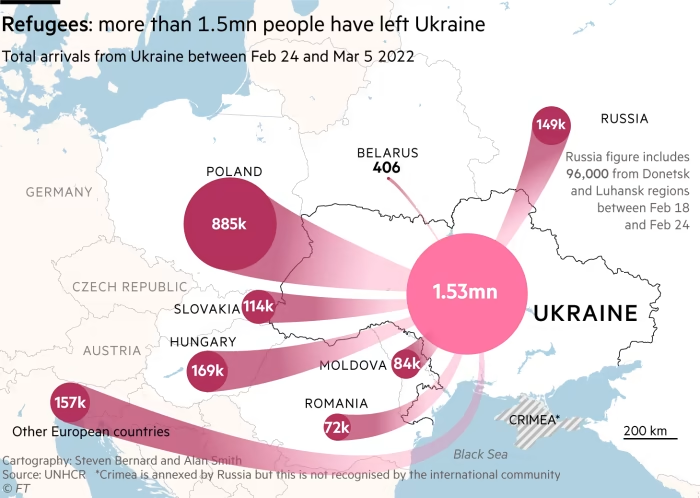

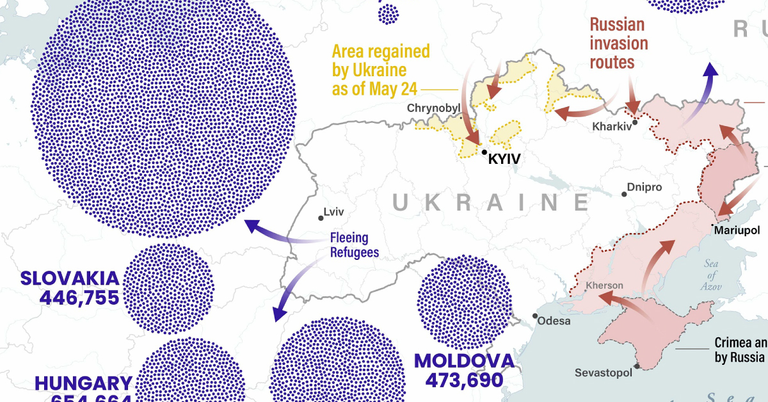

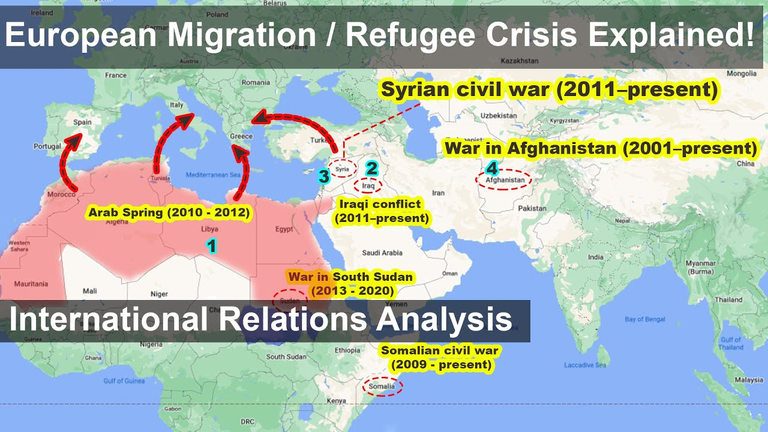

So let's get straight into it. Why has immigration been rising up the EU's agenda recently? Well, the fundamental reason is an increase in migrant numbers. While the EU has seen a significant increase in what sometimes known as regular migration, largely as a result of 4 million or so Ukrainians that have fled Putin's invasion, it's also seen a significant increase in what's known as irregular migration, i.e. asylum seekers and undocumented migrants. In 2022, the EU received over 900,000 asylum requests, a rise of more than 50% when compared to 2021 and the highest figure since 2016. And provisional data from this year suggest that asylum requests were up another 28% in the first half of 2023, which would imply an annual figure of about 1.2 million. Similarly, the EU's border agency Frontex detected over 300,000 unauthorized arrivals in 2022, the highest number since 2016. Now, these might be Europe wide figures, but certain countries have been acutely affected. Italy, for example, has received over 130,000 irregular migrants so far this year, already overtaking the total number from last year. Anyhow, these rising numbers have exposed and highlighted the various flaws with the EU's current migration system.

Now, to understand the problems with the current system, we need to go back to the mid 90s when the EU first introduced the Schengen Area. For those of you who don't know, the Schengen Area allows visa free travel i.e. freedom of movement between member countries and today comprises of the vast majority of EU countries and even a couple of non EU countries, covering a total area of over 4,000,000km² and 423 million people. Now, while Schengen's introduction was celebrated as a great European success, it's also created an anxiety in some member states that other states would now have little incentive to properly police their borders, because without intra EU borders, they could just push unwanted migrants onto other Schengen Area countries. Now, to assuage this anxiety, the EU introduced the Dublin Accords, which required irregular immigration to be processed in the country of arrival. That means if, say, Italy lets a whole load of migrants pass into France without processing them, France can send them back to Italy. Unfortunately, this system created the opposite problem. It put too much strain on the countries at the EU's external borders, often called frontier countries, which receive the majority of the EU's irregular migrants.

As such, when migrant numbers have risen recently, frontier countries have reacted by implementing illiberal immigration policies, which has provoked criticism from other EU countries on human rights grounds. Late last year, for example, France criticized Italy for refusing to take in a migrant rescue ship, which was then docked in southern France. And Italy is currently feuding with Germany over its funding of migrant rescue charities operating in the Mediterranean, which Italy thinks encourages irregular migration. Now, the EU has tried to remedy this issue with a voluntary solidarity mechanism, which obliges signed up non frontier countries to take in a few thousand migrants from the frontier countries. But it's not a permanent solution because, well, it's voluntary, which is why countries like Poland and Hungary haven't signed up to it. And both Germany and France temporarily pulled out of it after their spat with Italy. That's not all though. There are at least two other problems with the EU's current migration system. Firstly, while they do have a common internal migration policy in Schengen, the EU has no common external migration policy. The current system is a confused mess of national and EU legislation with a wide range of immigration policies.

Now some countries are more accepting of irregular migrants. In 2021 for example, Poland issued nearly 800,000 work visas to non-EU citizens, more than the rest of the EU combined. Similarly, some countries are more accepting of irregular migrants. In 2016, for example, Italy granted asylum to nearly 95% of Syrian refugees, while Croatia granted asylum to just 12%. The second problem with the system is that the policies are just often poorly enforced. Many frontier countries lack the resources to properly police their borders or implement their policies, and this is especially true in the Western Balkans, which was one of the most popular routes for irregular migration into the EU in 2022. The EU has tried to remedy this by investing in Frontex, its border security force. But even if the EU was able to perfectly police its borders, it doesn't have the administrative capacity to process the number of irregular migrants currently arriving into the EU. According to the latest data available, the EU currently has an asylum application backlog of about 900,000, including backlogs of over 100.000 in Italy, Spain, France and Germany.

The EU also struggles to deal with the 60% or so of asylum seekers who have their applications rejected, with fewer than 1 in 5 successfully deported. These two problems the intra European variation in attitudes towards external migration, and the fact that many European countries struggle to enforce their external migration policies, have seriously strained Schengen. Distrustful of their neighbours migration policies, many Schengen members have reintroduced border controls. At the time of writing, ten countries have formally reintroduced border controls using Shengen's emergency mechanism, with many citing the recent spike in irregular migration, and a handful more have been quietly increasing border policing without notifying the European Commission. Yet the idea then the EU currently lacks a cohesive external migration policy, and this in turn is undermining its internal migration policy. That's why, for the past few years, the EU has been trying to come up with a new external migration policy, and at the moment this seems to have two elements.

The first is the new EU pact on migration and asylum, first proposed by the European Commission in September 2020 and finally agreed by member states earlier this month. Now there's a lot in the deal and if you want to know more but perhaps the most interesting element is the mandatory solidarity pact, which aims to relocate 30,000 asylum seekers from frontier countries to non frontier countries. Specifically, if non frontier countries don't accept these migrants then they'll be fined roughly €20,000 per migrant refused, which has provoked some upset in countries like Poland and Hungary.

Poland and Hungary was not satisfied with the proposal, but they pushed us through, I mean, pushed through the proposal. So Hungary and Poland was totally left out of that. So after this, there is no any chance to have any kind of compromise and agreement on migration, because legally we are how to say it, we are raped. So if you are raped, legally forced to accept something, what you don't like, how would you like to have a compromise and agreement? It's impossible. -Hungary President Orban

Now, while getting this deal done is a diplomatic success, the deal still needs to be negotiated with the European Parliament and then ratified, which means that it's unlikely to come into force for another few years. It's not just that deal, though. The second element of the EU's new external migration policy is a series of deals with so-called transit states, i.e. those countries which migrants transit through before reaching the EU, which involves the EU giving these countries money to help them police their borders more effectively. The first of these deals came into force in 2016, when the EU agreed to give Turkey billions of euros to stem the tide of migrants coming into the EU, and its success encouraged the EU to sign similar deals with Libya in 2018, Morocco in 2022 and Tunisia in July of this year. But while these deals have been relatively successful, they have at least three problems.

Firstly, reducing migrant flows from one transit country usually only increases migrant flows from another. This is what happened in 2016 because while the deal reduced flows from Turkey, migrants just started travelling via Libya instead and when the EU reached a deal with Libya, then they started coming via Tunisia. Secondly, it's just unsustainable. Again, Turkey is a good example here. Originally, Turkey was happy to take in the migrants itself, aided by EU funding. But now Turkey has taken in an astonishing 4 million migrants and public sympathy within the country is apparently waning. Migration was a big topic in this year's elections in Turkey, and Erdogan is even trying to send back Syrian migrants to Turkish occupied parts of Syria. And the third issue is that it's just not clear that these deals are consistent with the EU's values and human rights. In Libya, for example, the Libyan Coast Guard, which is really more of a regional militia than a national police service, has been accused of various human rights abuses, including detaining migrants in prisons and using them for slave labor. Ultimately, given the competing electoral, demographic and economic demands, it shouldn't come as a surprise that there's no easy solution for the EU when it comes to immigration. But the continuing problems over the solidarity pacts demonstrate quite how politically difficult this problem is really becoming.

One person's problem becomes everyone's problem 😢, this is what wars generate.

!PGM

!LOLZ@tipu curate

Upvoted 👌 (Mana: 65/75) Liquid rewards.

lolztoken.com

It’s the bear minimum.

Credit: reddit

$LOLZ on behalf of elikast

(1/4)

Farm LOLZ tokens when you Delegate Hive or Hive Tokens.

Click to delegate: 10 - 20 - 50 - 100 HP@cronos0, I sent you an

It certainly is. Even if we sleep with our heads on our pillows in our peaceful environment, such wars will continue to take place all over the globe and disrupt the functioning of the surrounding nations.

Also, thanks for the generous curation.

Congratulations @cronos0! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCheck out our last posts:

it shouldn't come as a surprise that there's no easy solution for the EU when it comes to immigration."

I dont believe this if there is a will there is a way. How in the hell is a country not able to close the borders? Or there are no European sovereingn countries any more? It;s very simple as long as Europe is "offering" there will be waves of migrants. And our own population will pay the price.

If news will come out migrants have more chance of drowing than set on 1 cm on land. Things will change.💯