It's been about a year since the West first started imposing sanctions against Russia in response to Putin's invasion of Ukraine. These sanctions, which have been extended to include everything from an oil price cap to expulsion from the swift banking system were unprecedented in their scope. But it's not clear that they've been quite as effective as the West originally hoped. And in the last few weeks, there have been reports that Russia is evading export controls on advanced components like semiconductors by rerouting their imports via Central Asian states like Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. So let's unpack what's really happening in this article. First you need to understand how sanctions on semiconductors and other high tech equipment really works. Broadly, the sanctions that the West has so far imposed on Russia can be split into two categories export sanctions and import sanctions. Export sanctions basically apply to any sanctions aimed at restricting Russia's ability to export stuff like most notably oil and natural gas. This would include, for example, the suspension of Nord Stream two, the unilateral phasing out of Russian hydrocarbon imports in countries like Canada and the US earlier this year and the new G7 EU price cap, which was finalised in December and came into force in January. Now, because of the significance of hydrocarbons in the Russian economy, these export sanctions have attracted the most media interest and there's been a vibrant debate about whether they've actually been effective.

While they haven't received as much media attention, the West has also imposed significant controls on what Russia can import on the day of the invasion. The G7 placed export controls on themselves, thereby preventing Russia from importing goods from them. These self imposed export controls were mostly to stop companies in the G7 countries from selling stuff like semiconductors and other advanced components to Russia. Now, the intention behind these import sanctions was twofold. Firstly, they aim to do general damage to the Russian economy because basically every industry, from agriculture to car manufacturing, relies on semiconductors to some extent. And secondly, they aim to directly limit Russia's ability to manufacture or repair high tech military equipment like fighter jets and modern tanks, which rely on very specific advanced components which are in turn often made in the West. When they were first introduced early last year, these import sanctions were actually pretty effective and arguably more so than the export sanctions. As a result, Russian imports of these components fell sharply, and the Chinese companies that Russian companies tried to use to replace them turned out to be significantly less reliable.

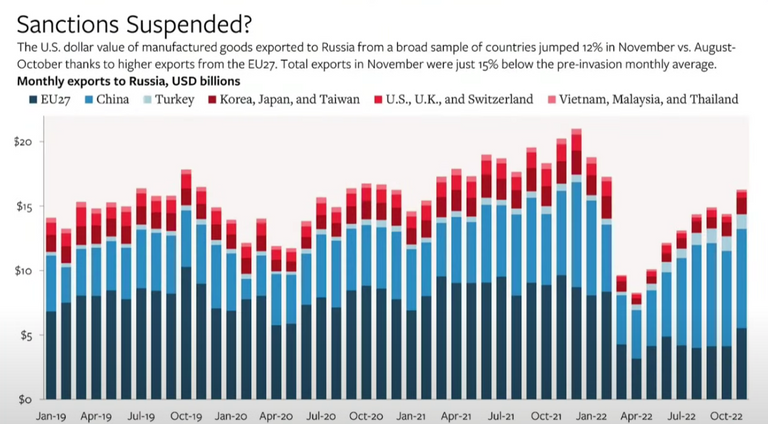

In October, a Russian newspaper found that Chinese parts had a 40% failure rate, compared to 2% for their Western alternatives. This led to a significant impact for Russian industries. In May of last year, for example, the Moscow Times reported that the number of cars in production in Russia had fallen by 97% year on year. These import sanctions also undermined Russia's ability to manufacture or repair high tech military equipment. Russia's import of goods with potential military application crashed by more than 60% in March to May of 2022 relative to September 2021, to February 2022. And this might partly explain why the Kremlin proved so reluctant to deploy its most advanced weaponry on the battlefield. The Russian Air Force, for example, has been conspicuously absent in Ukraine thus far. And this might partly be because repairing jets or building new ones require certain sanctioned components. However, in the past couple of months, it looks like the efficacy of these kind of sanctions has started to wane. Russia has started importing slightly more stuff from the West, presumably because Russian companies have found sneaky ways around the sanctions. But more significantly, Russia's Central Asian neighbors, which aren't under sanctions, have massively increased their imports from the West. As such, while total imports into Russia are still down from their prewar average, total imports from Russia's Central Asian neighbors are up 80%.

Now, unless domestic consumption in Kazakhstan is up 80% year on year and it isn't, then this suggests that Russian companies are rerouting their trade via central Asian companies to try and get around sanctions. For example, according to data from the EU's Eurostat database, Kazakhstan imported €1 million worth of washing machines from the EU in December 2022. This is four times as much as the previous year, and those washing machines are clearly going from Kazakhstan to Russia, where they're stripped for parts. And this would explain why the Ukrainian army has begun to report that they're finding microchips in captured Russian military equipment that were clearly repurposed from everyday household appliances. Now, according to data from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the worst culprits here are Armenia and Kyrgyzstan, who as of July last year saw their imports from the EU, jumped by 70 and 75% respectively. In a way, this follows a more general pattern With sanctions, they're most effective when they're first introduced, but their efficacy wanes as the sanction country. Figures out ways to work around them. A similar thing has happened with export sanctions too. The dollar value of Russian exports collapsed in March but have ticked back up to their pre-war average. So what should the West do about this?

Well, the obvious solution is secondary sanctions. Secondary sanctions are basically sanctions on third parties that do business with a sanctioned entity, even if they're not under the sanctioning country's legal jurisdiction, for example, because the US has imposed secondary sanctions on the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, anyone who does business with the IRGC can be cut out of the US's entire financial system. Similarly, the US could say that any Central Asian country that does business with, say the Russian army would also be cut out of the US financial system. However, secondary sanctions are pretty risky, not least because they would really irritate those Central Asian countries. So instead the West might be better off using carrots rather than sticks and providing incentives for those Central Asian countries to reduce their trade with Russia. All in all, if the West wants its sanctions regime to maintain its efficacy as the war drags on. They're going to have to become more creative about their implementation of sanctions and whether they can do that. Well, that's an open question.

Congratulations @scientify! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

Your next target is to reach 600 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCheck out our last posts:

Support the HiveBuzz project. Vote for our proposal!