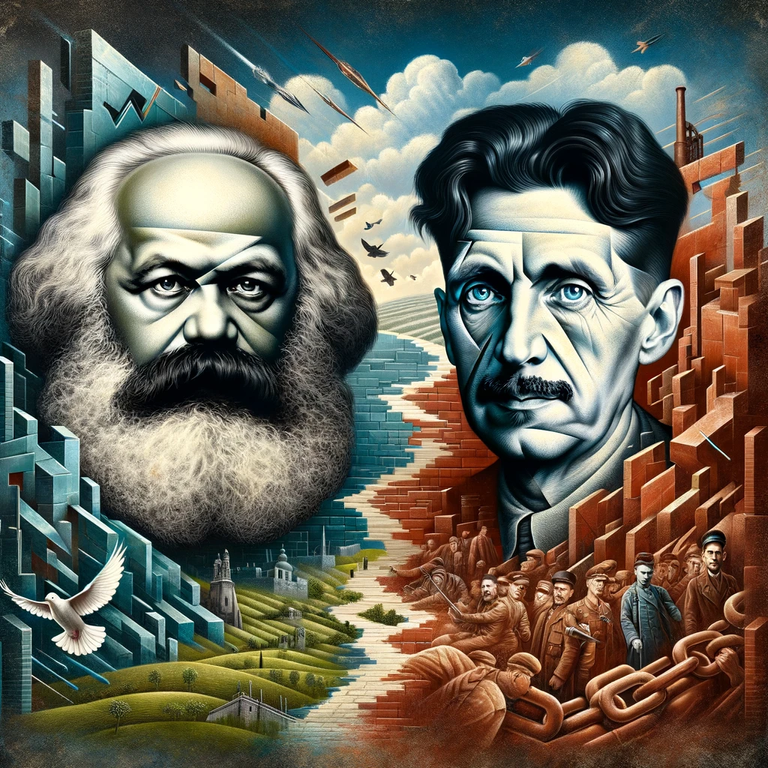

Creating a fictional debate of this nature requires a nuanced understanding of both Karl Marx's communist philosophy and George Orwell's critiques of totalitarianism, as well as their potential views on a modern geopolitical issue. While Marx did not write about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict specifically, one could extrapolate that his views would focus on class struggle and the dynamics of capitalist society. Orwell, on the other hand, was skeptical of concentrated power and propaganda, which he might relate to aspects of the conflict. Below is a fictionalized, abbreviated sample of what such a debate could look like:

Orwell: “In the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, one must consider the role of power and its abuses. It is the concentration of power that leads to the oppression of the Palestinian people, similar to the way I depicted the oppression in '1984'."

Marx: "But George, you are only scratching the surface. The root of this conflict lies within the capitalist mode of production, which pits the bourgeoisie of nations against the proletariat. The struggle between Israelis and Palestinians is but a shadow of the global class struggle."

Orwell: "Karl, while class struggle may indeed play a role, you must not ignore the nationalistic and ideological narratives that fuel this conflict. It is not merely a matter of economic class, but also of cultural identity and historical disputes over land and sovereignty."

Marx: "I would argue that nationalism is a tool used by the ruling classes to divert attention from the true struggle. The bourgeoisie uses nationalism to keep the proletariat in check, to keep them from rising against their oppressors."

Orwell: "And yet, nationalism exists outside of mere class control. It is an expression of a people's history and culture. One cannot reduce the attachment to one's homeland simply to class dynamics. The conflict is as much about self-determination as it is about economic conditions."

Marx: "You speak of self-determination, but what of the Palestinian workers? Do they not also deserve to be freed from the shackles of their economic conditions? It is through the lens of dialectical materialism that we must view this struggle, as one against capitalist exploitation and imperialism."

Orwell: "The question then becomes how one can ensure freedom for all parties involved. My fear is that in the pursuit of an ideological purity, whether it be communism or any other system, we overlook the individual's right to freedom from oppression."

Marx: "True freedom can only be achieved through the abolition of class societies. Only when the proletariat has risen, in Palestine and Israel alike, to overthrow their capitalist chains, can there be a possibility for peace and genuine self-determination."

Orwell: "But we have seen the dangers of revolutions that do not consider the individual – they can lead to totalitarianism. Any resolution must guard against the rise of tyranny, even under the guise of equality."

Marx: "The proletarian revolution is different. It aims to dissolve all power structures and create a classless society. In such a world, the conflicts we see today would become obsolete."

Orwell: "One must be cautious, though. Ideals are one thing, but history has shown us that they rarely translate into reality without corruption or loss. The human factor, with all its flaws and unpredictability, must be accounted for."

Marx: "That is why it must be a continuous struggle, a permanent revolution, until the state itself withers away and we are left with a communal society where such conflicts are a thing of the past."

Orwell: "A noble goal, Karl, but one fraught with its own perils. As I've written, 'All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.' Even in a so-called communal society, some will strive for power over others."

Marx: "And so the debate goes on, but we must not lose sight of the material conditions that shape society. It is there that we must enact change, for the betterment of all humanity."