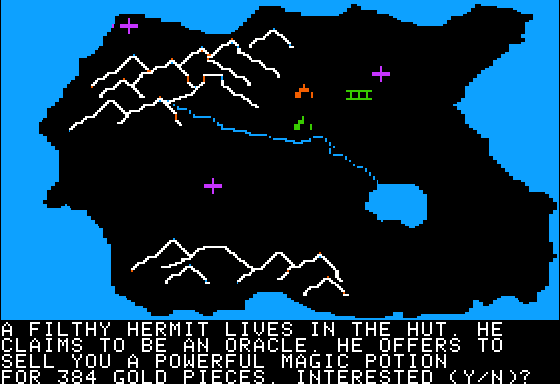

Modern gaming is kind of a modern-day miracle when you think about it. Even the previous generation of consoles render up graphical and auditory experiences that would have seemed impossible twenty years earlier. For a kid who started playing games when they looked like this:

... the idea that I'd one day be playing a game that looks like this:

... was unthinkable.

Or was it?

I'm a huge fan of retro gaming. Every time I come home with a new PS1 or Super NES title, my wife dies a little more inside. But as I've gotten older, and my reflexes have atrophied, I've found more and more enjoyment from just reading the periodicals of the days. There's something wonderful about not just the memories of palpable excitement when I'd come home from the store with a new issue of EGM but also the excitement that reverberated off the pages as the folks who got paid to play these things for a living struggled to express just how awesome this stuff was.

Maybe I'm reading the wrong places, but modern games journalism seems shot through with cynicism and anger, quick to jump on any perceived flaw and crucify the developers over it. Maybe in some cases that's warranted, but what I really think happened is that in the last ten to fifteen years, games started looking so good we no longer needed to engage our imaginations the way we used to. Without that extra special something your imagination provides, it's easy to fall into the belief that everything looks and feels the same, that those grand experiences of gaming yesteryear are fewer and farther between if they even exist at all.

I'm not here to doom and gloom, because those experiences do exist and can still happen. But I think collectively, we've tempered our expectations to the point that even when developers give us exactly what we said we wanted, we're still disappointed because it feels like something is missing. I'm here to postulate that missing ingredient is imagination: not among the game developers, but among the end consumers. And this is a huge problem, because it's not something devs can solve by throwing more money, or man-hours, or technology at it.

Imagination comes from within. It must be carefully nurtured. So much of what makes those classic games "classic", I think, has to do with how they were forced to skirt the boundaries between realism and imagination. There's an enormous chasm between what is realistic and what is imaginarily realistic, and modern games have been steadily eroding the size of that chasm for decades.

That first screenshot up there is from the game Atlantis for the Atari 2600, published by Imagic in 1982. And despite its blocky look, believe me when I say this was some top-notch visual work for the system. The concept is simple: the underwater city of Atlantis is under attack by alien invaders, and your job is to use your three gun turrets to destroy the attackers. The ships vary in speed, but each time they cross from one side of the screen to the other, they drop closer to the city. Once they reach their lowest point, they start firing their own weapons and will vaporize one of the city installations under your protection. There are six city targets and your main central gun turret to protect, and when the last one is destroyed, the game is over. Here's some video footage, courtesy of World of Longplays, so you can see this in action:

On the surface, this isn't terribly exciting, I will admit. But you're just watching a video. Actually playing Atlantis, on the other hand, is a pulse-pounding experience. The simplicity of it requires your imagination to do all of the heavy lifting, otherwise you're just left with bleeps, bloops, and flickering colors to tell the story.

But therein lies the genius: Atlantis worked on me as a child of five because I bought into it with my imagination. It required heavy lifting, but my kindergarten brain was more than up to the task. And as I grew up, and games got more technologically advanced, my brain still had to do that lifting. Even when we went from depicting Imperial AT-AT walkers like this...

... to this...

... to this...

... there was still a strong reliance on a gamer's imagination to fill in the gaps.

But then they started looking like this:

Nowadays, they look like this:

And, look, I'm not saying that's a bad thing. Star Wars fans have been begging to play games that let us feel like we're right in the movies for forty years. The fact the technology is at a point where we can do that is phenomenal. But what I am saying is once you reach the point where you no longer have to squint to tell that's an AT-AT, when your brain isn't having to fill in any of the details, because they're all there, right down to the carbon scoring and fully-articulated joints, then I think for a lot of us, the fun takes a hit.

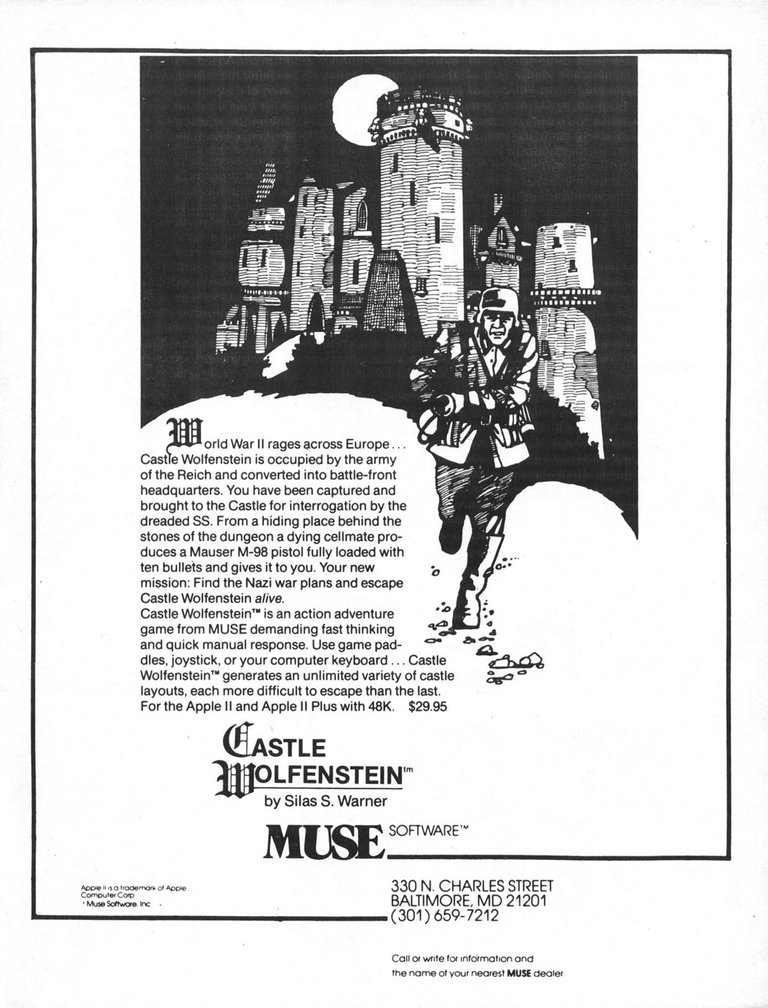

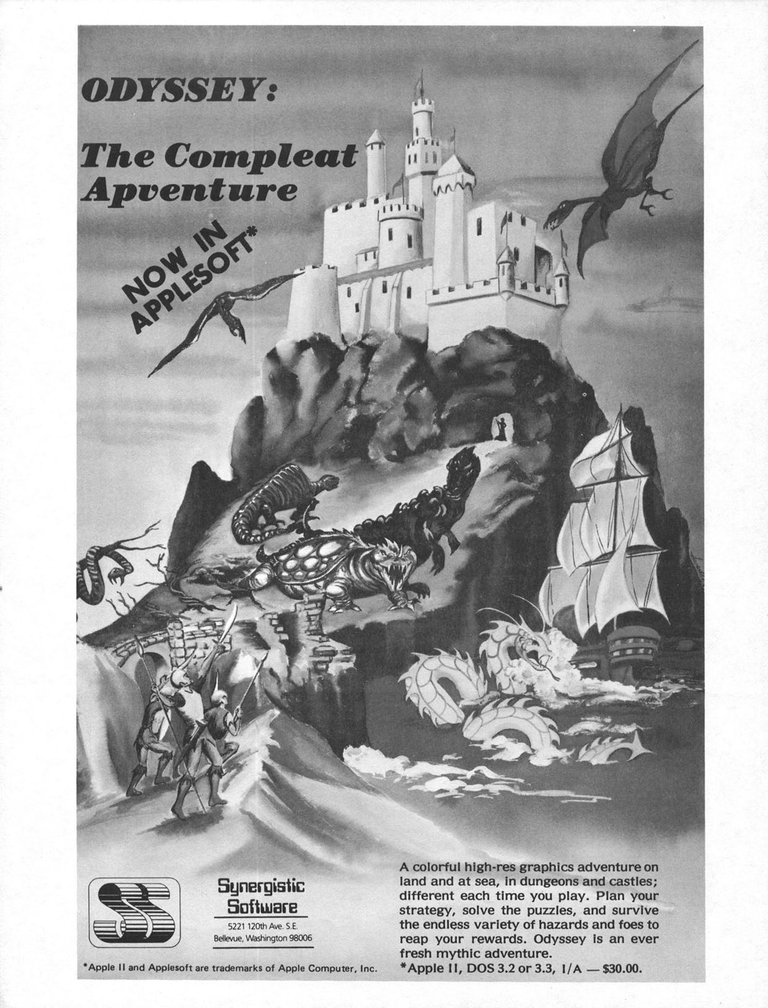

If you ever look through the pages of old computer magazines, you'd see imagination being used by game publishers all the time to sell their wares. Take this ad from the first issue of Computer Gaming World for Castle Wolfenstein by Silas Warner back in 1981:

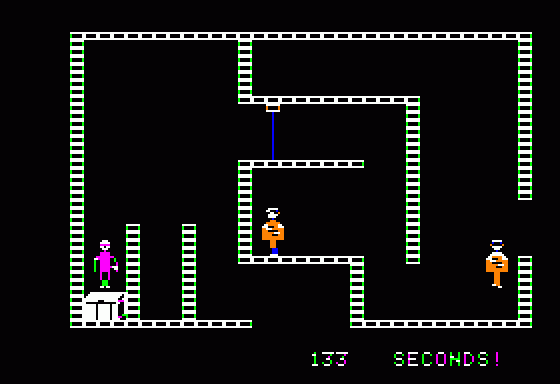

One thing you'll notice about games advertising from the early 80s is that you rarely, if ever, saw screenshots of the game in action. That's because when Castle Wolfenstein was released for the Apple II home computer in 1981, it looked like this:

That ad copy and illustration worked because, as a computer gamer, you knew the Apple II wasn't going to render life-like representations of old German castles and patrolling Nazi guards. The devs knew it couldn't do that too. So, instead, they salted your imagination with what they intended the game to look like in your mind. You read that ad copy, and you can almost feel the oppressive atmosphere of the dungeon, stone walls weeping water, your dying cellmate passing over a pistol, and with his last breaths telling you to live, find the plans, and get them back home before it's too late.

Then you read further that the game can generate an unlimited variety of castle layouts, you can play it with your keyboard or a joystick, it requires fast thinking and quick responses, and hell, a game you can experience anew multiple times even after you beat it sounds like a hell of a bargain!

Some of you are probably laughing that people in 1981 paid $29.95 for what looks, graphically, like a slightly more complex version of the arcade game Berzerk. But you have to remember, back then, people didn't buy a game for the graphics. They bought it for the challenge it brought to the imagination.

Nowadays, if a publisher advertised a game without showcasing a single screenshot, gamers wouldn't go anywhere near it, because graphics are the single easiest way to sell to the modern gamer. "See how pretty this looks? It looks even better in motion, so preorder our $70 limited edition and we'll give you an extra cosmetic goodie to show off how awesome you are!"

And we keep falling for it, because we believe that's exactly what we're looking for.

Of course, playing Castle Wolfenstein today and getting any enjoyment out of it without first putting on your +3 Rose-Tinted Bifocals of Nostalgia is almost impossible. There are myriad ways the industry has iterated and evolved the stealth action genre in the intervening decades. Playing it now, the main emotion it induces is boredom: every action you undertake, from searching a chest to dragging a guard's body out of view to frisking a Nazi while you hold him at gunpoint takes time. Real time. So when you see "133 seconds!" in that screenshot, that's the amount of actual, real, 1:1 time you spend, sitting at the keyboard, while your guy performs that action.

Warner didn't implement this design choice because gamers were all more patient back in the early 1980s (although with as long as it took to load some games off the floppy disk or, heaven help us, the cassette tape, we kind of had to be), he did it because that time is baked into a risk/reward system. Searching a chest in a game today is as easy as pressing the 'X' button a couple of times: a second or two, and you're on your way with your treasures.

Searching a chest in Castle Wolfenstein meant actively taking time you could be using to do literally anything else, including escaping (you have a time limit to find the plans and get out of the castle), and applying it to looting. If there were guards patrolling around, you had to weigh the risk of getting caught with how desperately in need of supplies you were, and hope that the chest you're digging through contains something useful like a grenade or bulletproof vest, and not one of the many interesting but functionless items like food, bottles of Schnapps, or Eva Braun's secret diary. On the whole, Castle Wolfenstein was complex, but not terribly complicated, and this system played a part in that.

But that was then. Forty years later, game designers do things differently. They no longer have the luxury of telling players, "It's going to take you two minutes and seventeen seconds of real time to loot this cabinet. Still want to do it?" And heaven knows, the older we get, the less patience we have for mechanics that don't instantly cater to our collective dopamine addiction.

Castle Wolfenstein has long been supplanted in the realm of stealth adventure titles in pretty much every way imaginable: controls, sound effects, graphics, game design, presentation, everything. But one area where it hasn't been usurped, and what keeps people playing now, is the trust it places in the player's imagination to fill in the gaps. There are many of those gaps, for sure, and your imagination will get quite the workout for it. But imagination is a muscle, just like any other. The less we use it, the more it atrophies and the harder it is to get it to engage, because we start to feel like we shouldn't have to.

Maybe that's the crux of this essay: maybe we, as gamers, have reached the point where we feel like we shouldn't have to engage that muscle, that the developers should do it for us. But the devs can only take that so far. I think this unspoken rule is partially responsible for the resurgence in retro-looking (if not exactly retro-playing) games, especially around the indie scene. Those games work by forcing us to exercise the most critical muscle we have when it comes to playing games.

I don't know what the solution is. There probably isn't one. We can't just go back to playing the original Doom or Quake or Castle Wolfenstein or Atlantis and pretend there's nothing new. Nor should we want to. Maybe the solution comes from developers figuring out some new way to trust and engage our imaginations, but I don't know what those could be. Every push forward is made in the name of more realism, more graphical pizazz, more audio fidelity, and we reward these never-ending Call of Duty franchises with billions of dollars so they will do the same, only more of it, next time.

What I do know is that in the last twenty years, we hit a point where the number of gaps our imagination had to fill in while playing video games crossed some sort of invisible Rubicon. We felt the change, but we didn't know what it was and couldn't articulate it. At least, I couldn't. Not until now.

Hell, maybe not even now.

All I know is, there's a part of me who looks at old ads for computer games he never played and lets his imagination run wild with all the outlandish possibilities. Not because the games look like this:

But because, to me, they look like this:

I totally agree with this sentiment. I think you and I are a similar age because I recall when the story was sometimes absolutely paramount to making a good game. With limited space on carts they couldn't just bog the game down with massive cinematics, there needed to be a really compelling story especially in RPG's. When I think about early Final Fantasy games or Phantasy Star games, they really had to hook you with a good story because they couldn't possibly blow you away with stellar graphics because it wasn't possible. These days, I think a lot of studios try to wow us with realistic graphics without putting much into whether or not the game is actually going to be fun. I am turned off by many modern titles because of things like this and also massive load times because we've basically got to load a damn movie just to introduce you to a new area.

Congratulations @modernzorker! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

Your next target is to reach 240000 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP