There’s a dragon in the room. Let’s talk about it.

It isn’t actually cancer, although that dreadful beast became the avatar of unavoidable tragedy to Ryan and Amy Green, two married theater kids whose son Joel lived with brain cancer and died of it at the age of five. One dragon is the expectation of normalcy that makes Joel’s story so bizarre and threatening and that underscores the irony of his story being told in the format of a niche point-and-click adventure game.

Whether that is the final dragon, we’ll see in the end, if we make it to the final boss battle.

Into the boiling cauldron of the long, complicated debate over videogames as a form of art, a cauldron which was writhing with all the wyrms that had been poured into it from the opened cans of the various social debates that had been rocking the Internet during the 2010s, the Greens dropped a dramatic anomaly that could only have been created from their specific set of circumstances and perspectives.

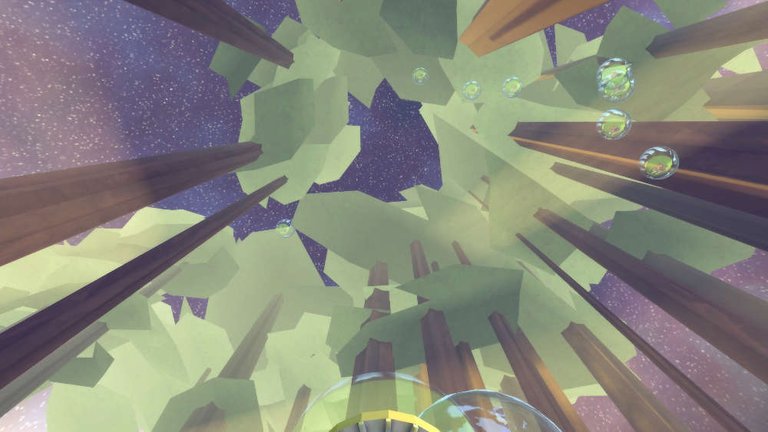

The state of the pot at the moment when That Dragon Cancer was introduced into the mix, as well as its positioning within the independent videogame scene at the time, have made its introduction an inseparable memory for those of us who cared about the efforts involved in supporting independent videogame development. I had purchased an Ouya. The Oculus Rift was going to open our eyes to literal new dimensions in wide open development toolkits, operated by an intricate series of valves which allowed anyone with a working knowledge of hardware and hammers to blow off steam. Everything was about to be available on Linux. Everything was opening up, opportunity seemed to be abounding, and Red and Blue were left behind in the bipolar past in preference for the new Purple. And in the emotional shade of this deepest purple arrived a game that would have been one of the standard bearers of this new freedom – a democratic crowd supported project, a project validated by experts at the forefront of the companies pushing for the new openness, an oldschool neo-console game for the old gamers, an artistic experience for the indie kids.

Arriving at the juncture of all these expectations and trends, That Dragon Cancer was destined to disappoint many. It did so in perhaps the most daring and authentic way possible. It flaunted its own uniqueness, a pointed uniqueness drawn from the circumstance of its subject matter as well as the unusual perspective coming out of the experience of Ryan and Amy Green. Only a couple of crazy Christian artists could have ever made something so starkly heartfelt yet brazenly unapologetic, so monstrously self-aware and yet so tremendously vulnerable, so edgy and yet so gentle. Praised both mildly and enthusiastically by many professional reviewers, the game naturally and understandably has had its share of harsher criticism.

The game is intensely self-aware at every level of analysis. The companion documentary film, Thank You For Playing, not only intensifies the self-awareness of the whole game project by its very existence, but also reveals the direct deliberation that the Greens undertook regarding the minute details of their everyday horror while their son was dying. The documentary almost seems like an answer to the critics’ questions about why such a thing as That Dragon Cancer should exist at all, and the answer is a defiant portrayal of the creators’ excruciating mindfulness.

There is something monstrous in the fact that the Greens conscientiously worked through their sons death so minutely that they were able not only to tell the story of his death, but to simulate it. This is especially striking upon viewing Thank You For Playing, wherein the character of Amy Green steps out from backstage to show the critics her technique. Is it even possible to authentically portray oneself? Is the portrayal of oneself automatically disingenuous, because it is the self trying to represent itself? The re-enactments in the game feel somewhat alien from the external portrayal of the real people, the real artists. Part of this is inevitable due to the alienation from the subject in any form of art; part of this is a further alienation due to the simulatory nature of videogames. Here the alienation between the simulation and the presumably more real external perspective of the artists is so distinctive because it feels so deliberate. When playing the game and then watching the documentary, I was astonished by the Greens’ willingness to make what must inevitably be an inadequate and vulnerable parody of their own son’s existence and death.

This jarring out-of-body experience may be what those negative reviewers are reacting to when they question the legitimacy and decency of the whole project. The fact that Ryan and Amy Green had to consciously model their own suffering is simply too bizarre and threatening for many people, who can only back off in confusion or accuse the Greens of being coldly mercenary. The position of the game within its scene during its moment is of little more use than the personal reputation of its creators, but understanding how this weird little game challenged the norms of digital society can inform us regarding how art plays its hand.

For That Dragon Cancer is an art game, and that fact alone makes it a key player in the broader discussion concerning the role of art in videogames. Should videogames be conventionally fun? Can they legitimately make ideological or social points? Is it fair for game developers to make a game to be deliberately un-fun in order to take the players through an artistic experience? This debate is both overshadowed and intensified by the self-awareness in That Dragon Cancer. The impact created by the apprehension of the self-awareness is the most dramatically artistic quality of the game. But even if taken at face-value for its content without overthinking its context, it is still obviously an art game.

The game is a work of art in the strictest sense possible – it is an artifice, something deliberately made, more than a mere aesthetic – and not only made as a representation, but designed to shatter the psychological walls that people construct around its sensitive and intimate depiction so as not to have to endure the awareness of the full significance of such a reality. Yet it may not be true that such was the explicit design of the creators. In Thank You For Playing, Ryan Green explains that his goal was simply to ensure that his son would not be forgotten, while Amy Green’s motivation appears to have been defiance of social attitude that raising and caring for a terminally ill child may not be worth the effort. (She makes this point in Thank You For Playing. The family also created an illustrated rhyme book entitled He’s Still Alive, published before Joel Green passed away.) If there is any agenda in the game, it is this: a stalwart defiance of death through embracing it.

The paradox of this strange game’s strange artistry incorporates a recurring theme in the game’s content, which may well be considered strange in its own right: the religion. We don’t necessarily need to mention it. The faith of the Green family as portrayed in the game is part of the content; and although that content is relevant to its artistic effect, many players are able to leave the subject of religion within the domain of content and react to the game as a piece of art depicting a fully human situation. That may be enough said. Yet lest we be accused of letting sleeping dragons lie, let’s consider how the religion in the game influences its public perception and its internal narrative journey.

Some players reject the game more or less outright due to its religious content. Out of 100 negative reviews on Steam – most of the negative ones – 38 stated or strongly implied that the religious aspect of the game was the reason why they were giving it a downvote. That third out of the negative reviews included anecdotes of rage-quitting and requesting a refund at about the mid-point in the game. Enough people complained about a specific triggering point about half-way through that there must really be something upsetting to a segment of players, but I am not completely certain about what exactly the triggering material is or whether there is a very specific moment that is so triggering.

To be sure, the belief in an afterlife in Heaven is depicted with both visceral emotion and a sense of willfully unshakable resolve – and it is only in the belief in Heaven that this unshakable certainty is evidenced in the game. A large part of the narrative is the experience of disillusionment. The game depicts Ryan Green’s pessimism and despair and Amy Green’s blind confidence in a victorious healing, which never was to occur. It is not an external judgment upon the game’s narrative to label Amy Green’s specific form of confidence as blind, because the narrative structure itself characterizes it that way. After viewing Thank You For Playing and observing how deliberate is the characterization of the game’s fictional incarnations of the two bereaved parents, it appears that the mistaken certainty of victory is part of the structure of the narrative, a confession of a kind of failure. This is clearly not the structure one would choose if one were attempting to proselytize, as a few Steam critics accused. The game is not religious in that particular sense. Instead, it is religious in two other ways:

- Christianity is part of the aesthetic – both of the narrative content and of the emotional theme that the artistry is conveying.

- The Christian hope is an inseparable part of the artistic expression itself, even considered apart from the content.

To the first of these, the game contains the Christian experience of the parents as well as the religious cultural background behind the world of American families enduring terminally ill prognoses while navigating the institutional healthcare system. This kind of religious theme can be used as a tool of artistic impact or narrative storytelling, or it can be more-or-less inconsequential cultural whitewashing. Here the religious content is part of both the story and the cultural milieu. As such, the Christianity portrayed in the game has the potential to be interesting apart from whatever value the faith experience might give it, as some of the religion-critical reviewers have noted.

Yet even with all this religious and specifically Christian content and framing, the game would still be able to play the art card in its typical and ultimately secular hand, if it weren’t for the second way in which the game is inherently religious. As a work of art, the game causes players to really see something that would conventionally be psychologically repressed or socially whitewashed – in this case, terminal illness and death in a family setting. As art, the game can go no further than showing its subject in its alienness, its inherently disturbing and fearsome aspect, but also its grief-infused beauty and surprising gentleness. If the game were to make an explicitly formulated statement about grief or death or palliative care, it would be stepping beyond art – which might not necessarily contradict or weaken the actual artistry. That Dragon Cancer does not go very far beyond art, certainly not to make a religious statement. Hypothetically it could have – and then it would have been religious in a third way, and the whole affect and meaning of its content would have had to have been re-evaluated. Such a statement could have been anti-Christian or pro-Christian; for instance, it could have told the story, “Our child died and God didn’t save him; therefore we gave up on Christian dogma” or it could have been “We tried prayer and it didn’t work; therefore we no longer believe in emotional worship or faith healing and instead have turned to deeper historical theology.”

Yet the game does not say either of those things. If it had, it would have had a clearer audience and a more clearly defined position within the media landscape. Instead, it stops at the portrayal of grief and the shock of stressed faith in its psychological manifestation to the believing parents. I don’t believe it makes any further judgment on the nature of faith or anything else. The final scenes portraying Joel in Heaven are portrayed out of a Christian worldview, but they are not obviously oriented toward any purpose other than to depict. Insofar as it declines to make much of a point, it both upholds the existential reality of the experience it depicts and remains primarily artistic.

Yet it could have been primarily artistic without really being Christian art, even while containing plenty of Christian content. Here is how it is intrinsically religious at the same fundamental level at which it is intrinsically artistic: the orientation of its stark artistic expression is toward a transcendence. It could have shown the stark experience in an ordinary experiential way, and then it would have been merely art. Many works of art can use Christianity for its themes of death and suffering without really exemplifying the transcendent Christian hope. In That Dragon Cancer, that hope most explicitly comes by way of a belief in the existence of an afterlife in Heaven, which Ryan Green expresses in Thank You for Playing and which is really the only theological facet of the game.

Those who criticize this Christian orientation as being a cheap emotional bandaid for the raw artistic pain of the subject might have a point, if they’re addressing the affect of the afterlife theology to the overall emotional impact of the game. If this is a flaw, it is certainly an honest one. An art game that engages Christian theology more deeply could be imagined, but That Dragon Cancer is only what it is, and it is already quite a lot of things.

For being so self-aware, the game actually seems oblivious to its own potential offensiveness. There is no malice here, no expressed desire to scandalize a community that has misunderstood the game’s grieving creators, no desire to burn the world because the pragmatically ineffective faith may have left them burned. There is a simplicity to the Greens’ artistic offering. The stark sincere grief is what it is, and everyone playing is sent back to their lives to make whatever they will of it.

This is how this weird game ultimately strikes a mortal wound to its dragon. The dragon is not cancer, neither is it ultimately chaos or fear or social normalcy. The final dragon is cynicism; that is, it is the perspective warped by personal pain that people project on to others’ lives. By offering the story of their pain without bitterness, the Greens are extending to their audience an opportunity to retrieve a cleansed perspective.

Congratulations @strivenword! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s):

Your next target is to reach 30 posts.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPTo support your work, I also upvoted your post!

Check out the last post from @hivebuzz:

Support the HiveBuzz project. Vote for our proposal!