The Iban are a proud and resilient indigenous people from Sarawak, Borneo, known for their rich cultural heritage, complex oral literature, and deeply ingrained mythology. Iban culture is centered on a complex cosmology that closely connects the spiritual and physical worlds. This cosmology is reflected in their extensive oral traditions, which maintain the community's legends, histories, and values as passed down through generations by “lemambang” (bards) and storytellers. The celebration of "gawai," or feasts, is one of the most prominent manifestations of Iban cultural identity. There are various types of gawai, each with its own purpose and significance—Gawai Dayak (Harvest Festival), Gawai Kenyalang (Hornbill Festival), and Gawai Sandau Ari (Midday Feast), to name a few.

One of the most important celebrations is Gawai Antu, or the Feast of the Dead. Gawai Antu is a rite of remembrance and veneration for the spirits of deceased ancestors. This sacred feast embodies the Ibans' belief in the cyclical nature of life and the unbreakable tie between the living and the dead. My first memories of Gawai Antu developed within this rich cultural background.

My father's longhouse: Ng. Batang, Ulu Krian, Saratok. Image source: Youtube

I was ten years old when I first experienced Gawai Antu at my father's longhouse in Ng. Batang, Ulu Krian, Saratok. At the time, I had no idea what it meant; all I knew was that it was a rare and grand occasion that sparked a frenzy of activity in our quiet longhouse. Even now, decades later, I can still vividly recall the sound of gongs resonating through the wooden walls, the sight of elders dressed in traditional clothes, and the haunting invocation to deities and ritual prayers. It was a time of amazement and awe—a window into the deep bond that exists in Iban society between the living and the dead. Only later would I realize how this celebration encompasses our heritage and creates our identity.

Gawai Antu is not an ordinary festival. Unlike the annual Gawai Dayak, which celebrates the harvest, Gawai Antu honors the departed souls of our ancestors. People often only celebrate Gawai Antu once in a generation. It involves years of preparation and requires a collective effort from the entire community. Families save tirelessly to host this event, which includes offerings, feasting, and elaborate ceremonies to bid farewell to the spirits of loved ones who have passed away. In essence, it is both a celebration of life and an acceptance of death as an essential component of our communal existence.

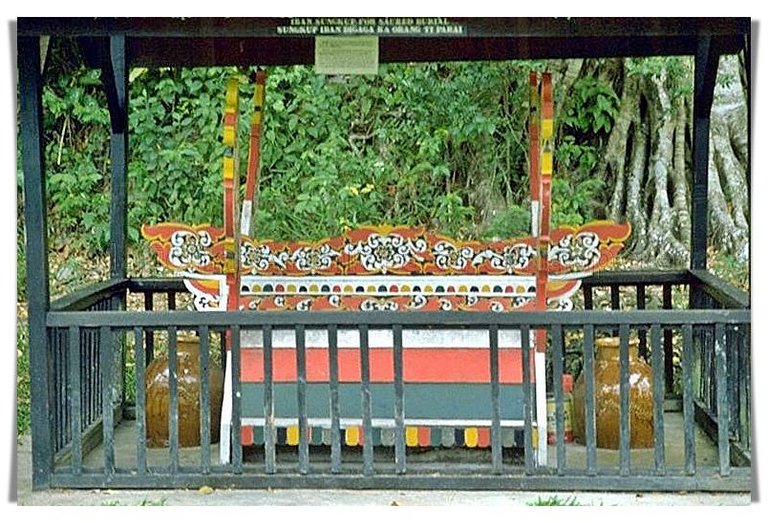

A "sungkup". Image source: National Archives of Singapore

As a child, my knowledge of Gawai Antu was confined to its surface elements. The complex rituals captivated me, while the sensory richness of the feast overwhelmed me. A lively environment filled with laughter, music, and the aromas of traditional cuisine transformed the quiet longhouse. They invited thousands of guests and relatives from nearby longhouses to this feast. I recall the men working together to create and decorate the "sungkup," or memorial huts, for the deceased. I recall watching the community's skilled weavers create the sacred "garung," or baskets, to store the "tuak Indai Billai," or Indai Billai's rice wine.

One of the most intriguing rituals for me was the "ngalu petara," in which men and women dressed in their finest traditional clothes and marched around the longhouse gallery to "welcome" the souls of the deceased and the gods. I also recall seeing a group of "lemambang" (bards) carrying "ai jalung," or special rice wine, in covered bowls while chanting "nimang jalung" to invite the spirits and deities from midnight till dawn. Poetic lyrics in this invocation depict the deceased's journey from "sebayan," or the world of spirits, to their former longhouse, the site of the feast. The "bujang berani," or men of valor who had accomplished significant achievements, received the "ai jalung" for drinking at 4 a.m. These moments felt meaningful, even if I only realized what they meant years later.

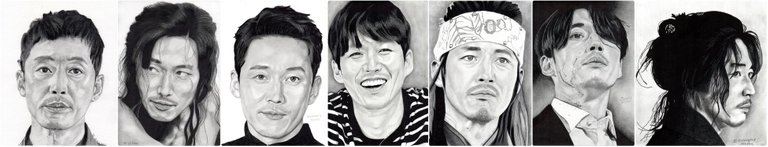

Image source: My sister

Only as an adult did I realize the significance of this festival. This festival is a profound expression of our connection to our ancestors and our commitment to preserving their legacy. In Iban tradition, life is cyclical, and death is not an end but a transition. Gawai Antu rituals uphold this belief by honoring the spirits of the departed and acknowledging their contributions to our lives.

Understanding this has strengthened my connection to my heritage. As someone who now lives away from my homeland, my recollections of Gawai Antu are even more poignant. They remind me of the importance of maintaining connection to my culture, especially when modern life frequently drags us away from traditional practices. Gawai Antu was a period when the longhouse community came together, bound by a shared history and purpose. It served as a reminder that the lives of those who came before us shape our identity.

"Bujang Berani", a man of valor drinking the "ai jalung".

Gawai Antu also carries a personal significance for me as an artist and writer. Writing about this festival allows me to explore themes of memory, identity, and belonging. In many ways, my writings serve the same purpose as the rituals of Gawai Antu in preserving stories, honoring the past, and finding meaning in the spaces between life and death. As our community navigates the challenges of modernity, I feel a responsibility through writing to preserve the essence of Gawai Antu.

However, this responsibility can also feel daunting. Many young people today, myself included, struggle to fully embrace our traditions. The world has changed significantly since the days of our ancestors, and the pressures of modern life often leave little room for cultural preservation. I sometimes wonder if my children would appreciate the significance of events like Gawai Antu or if they will dismiss them as relics of a bygone era. However, I am hopeful that through storytelling—whether in poetry, essays, or conversations—I will pique their interest and encourage them to explore their roots.

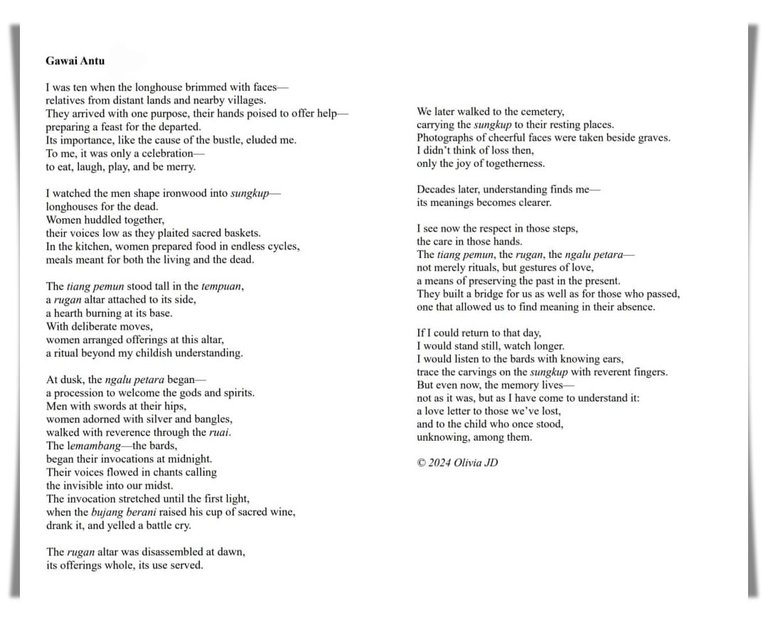

My poem, "Gawai Antu".

One of the most profound lessons I have learned from Gawai Antu is the value of remembering. This festival reminds us that our identity shapes not only who we are, but also who we come from, in a world that often prioritizes progress and forgets the past. Honoring our ancestors involves more than just paying tribute; it involves acknowledging the interwoven nature of their struggles, victories, and sacrifices in our lives.

As I reflect on my experiences with Gawai Antu, I am grateful for the sense of belonging it has given me. It has taught me to see life as a continuum, with the past influencing the present and the present shaping the future. My appreciation for Iban culture and its preservation has also grown.

Decades after my first Gawai Antu, the memories remain clear. The rhythmic gongs, graceful dances, and sacred rituals are more than just memories from my childhood; they are part of a greater story about connection, identity, and significance. Through Gawai Antu, I learned that honoring our ancestors means honoring ourselves, because we are the living embodiment of their legacy.

Note:

A documentary about Gawai Antu was made several years ago, you may watch the trailer here:

I don't have any photographs of Gawai Antu from my childhood. They are kept safely in my parents' home in Sarawak. The photographs in this essay are credited to the sources listed below each image. For more information on Gawai Antu, you may visit these sites:

That's it for now. If you read this far, thank you. I appreciate it so much! Kindly give me a follow if you like my content. I mostly write about making art, life musing, and our mundane yet charming family life here in Klang Valley, Malaysia.

Note: All images used belong to me unless stated otherwise.

Congratulations @coloringiship! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

Your next target is to reach 160000 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCheck out our last posts: