ENGLISH

For several days now, I've been trying to write this post... And the truth is, lately, I can't think about anything other than Venezuela. My country, my home.

Emotions haven't allowed me to sit down and reflect on them. That's what happens when something hurts you deeply: facing it and talking about it becomes a laborious task.

But here it is:

I was born in 1998, the same year and month when chaos erupted in my country—a chaos that continues to this day. I don't know anything other than what we're experiencing now. I've never lived outside Venezuela, and I don't even know much about life beyond its borders. So, this is all I know.

In 2002, 2014, and 2017, immense social upheavals and riots swept through Venezuela, expressing the will of the people—essentially, a rejection of the Chavismo ideology associated with the late former president Hugo Chávez.

Of all those years, 2017 was a turning point for me (and for much of my generation). It was the first year I actively participated in peaceful protests. At 18-19 years old, I lived through that period as anyone would who loves their home and wants to defend it. I also experienced these intense emotions as a fervent teenager; it was a traumatic and painful time for all of us.

During that period, my family and I woke up every day to the sound of tear gas canisters. The explosions and gunfire would start early in the morning. Over time, although the outside noises became familiar, I never truly got used to them.

Our house was centrally located in the city, where protests occurred almost daily. Many times, as I peeked through the iron bars of our home, I saw large military tanks stationed outside, their green color contrasting starkly with the residential surroundings. Soldiers pointed their weapons at our street. Tear gas canisters were often thrown over the fence, landing right in front of our house. We would retreat to our rooms, along with our frightened dogs, waiting for it all to pass while tears streamed down our faces due to the effects of the tear gas that permeated every corner of our home.

This isn't something I heard about or watched in a social media video; I lived it firsthand for months in 2017. And just like my family and me, thousands of Venezuelans survived that time—though it's essential to note that many did not.

In that year, I was studying at the university. For obvious reasons, the entire country—including universities—came to a halt for months. However, people still had to go to work; we couldn't remain completely idle for months. So, just like now, during that time, businesses operated on specific schedules, and the universities called for a gradual return to classrooms.

As I walked to the bus stop that would take me to the university, it was common to find bullet casings and pellets scattered on the ground in the mornings—hundreds of them. I even kept one in my bag as a tangible reminder of what I was experiencing. These were irrefutable physical evidence of the brutal repression by the National Guard. It's important to clarify for those who aren't familiar with Venezuela: civilian gun ownership is illegal in our country. Only the military and those authorized by the government are armed.

Since coming of age, I've witnessed the injustices and violations of rights that exist in my country. It's worth noting that not everyone shares this fate. Now, as a medical student, I've seen children in hospitals who worry when the doctor tells their mothers they need to buy specific medications and supplies. They ask me, "Doctor, how much does that cost, and where can my mom get it?" Is it logical or fair for a child to bear such concerns? Should a child have to worry about these things?

Now, let's talk about what's happening in Venezuela today.

I believe much of the world is aware of the ongoing civil rebellion against President Nicolás Maduro's government. On July 29, 2024, at 12:09 a.m., Venezuela would know Maduro's arbitrary reelection. Venezuelan voters had cast their ballots on July 28, with nearly 70% supporting Edmundo González Urrutia, the opposition candidate led by María Corina Machado.

María Corina was the true choice of most Venezuelans in the primary elections leading up to the presidential race. However, unsurprisingly, the current regime politically disqualified her. After several attempts, she ended up endorsing Edmundo González, who was already independently registered, so the government couldn't disqualify him as well.

Now, the question many may ask is:

How can we be sure that electoral fraud occurred in the July 28 presidential elections?

Apart from personal opinions and day-to-day observations—where it's challenging to find anyone content with the current government—the opposition has published original election records authenticated by QR codes. These codes confirm that each record was issued by a voting machine and show every vote cast by Venezuelans across all states. This information was made available on a website created by the opposition, anticipating potential fraud.

The result was quite clear: Venezuelans chose the opposition candidate, Edmundo González, as the new president of Venezuela, with an overwhelming majority of 67%, compared to Maduro's 30%. The remaining votes were distributed among other candidates.

As a consequence, protests erupted from the early hours of July 29—not organized by the opposition but rather reflecting the discontent of the Venezuelan people.

Why?

Because we all know what happened. We all lived through it.

On the afternoon of July 28, I headed to my nearest polling station for the vote count, and like me, many Venezuelans did the same at different centers. In the vast majority of these centers, Maduro had never won, except for a few parishes in certain states.

Various videos circulated on social media showing the actual vote count at each center, and none of them declared Maduro the winner. But beyond personal perceptions and social media videos, the official records exist and prove what I'm saying.

This fraud triggered not only protests but also brutal repression in the streets. It was expected—indeed, we all anticipated it, even if we didn't want it to happen.

How were the days leading up to July 28th?

Anxiety and anticipation permeated the streets, especially in the markets. On Saturday night, just before the fateful Sunday, some markets were chaotic: crowded with people making nervous purchases, meat and deli fridges empty, and basic food product shelves nearly bare. We all knew what could happen; unfortunately, it wasn't the first time.

A few weeks ago, while talking to an English friend who wanted to stay in the country during the presidential elections, she said she was excited about the event because she knew it wasn't just any election. In her own words, "You never know what might happen here." And that was precisely the case: after July 28th, there was a big question mark.

The plans we made for the week after July 28th were not definitive. Ultimately, we all said, "Well, it depends on what happens."

In my opinion, there were basically three scenarios:

- The most likely: massive protests and brutal repression if the Consejo Nacional Electoral (National Electoral Council or CNE) declared Maduro the winner.

- Intense (and perhaps tense) joy if the opposition won.

- Nothing significant happening, regardless of the outcome (similar to previous times when there was a sense of collective indifference).

Of course, I hoped for the second scenario, but I knew the first was more probable.

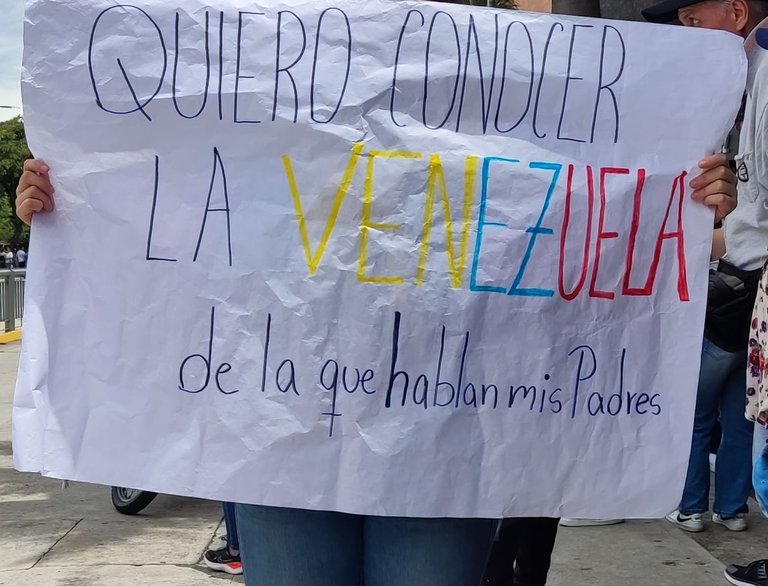

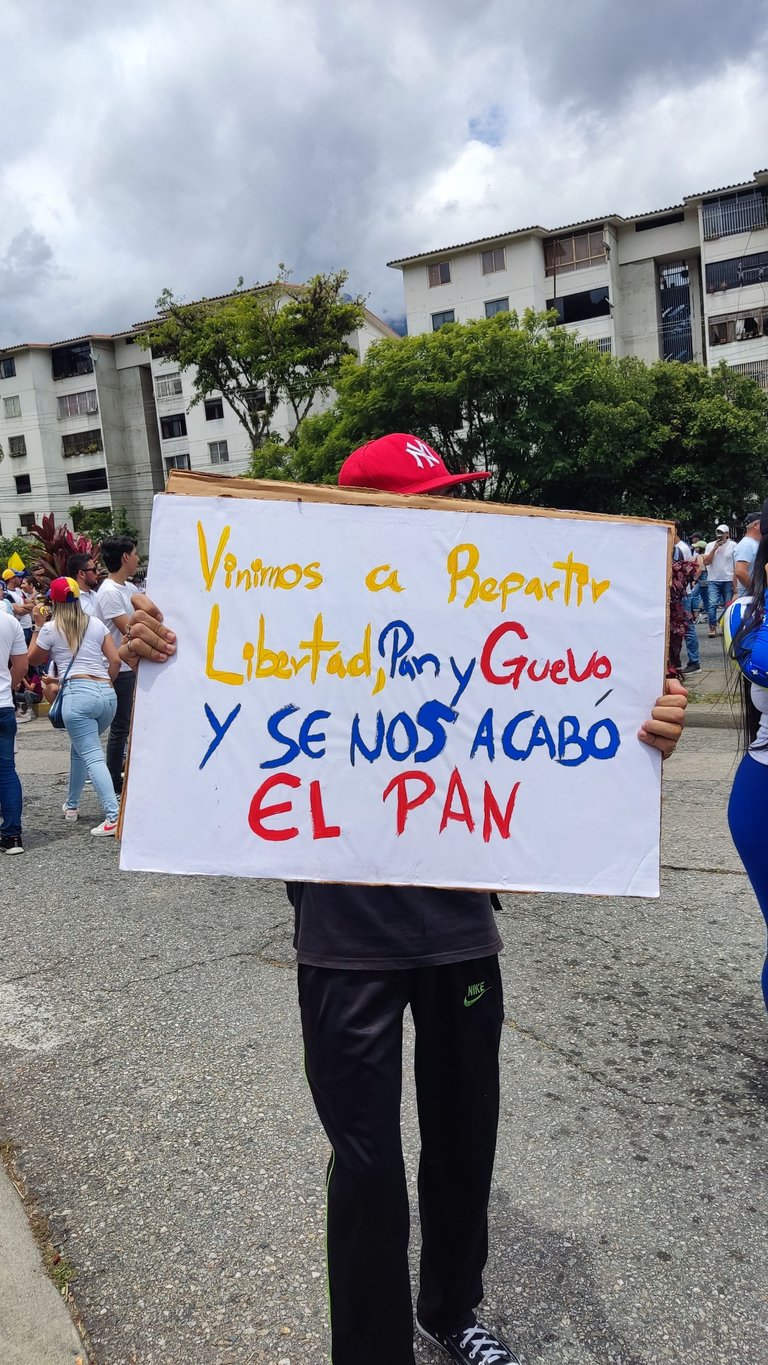

After Maduro's proclamation, a bewildering feeling of unease and disillusionment swept across the entire country. This inevitably led to spontaneous protests. Social media filled with images of protesters in the streets nationwide—brutal and terrifying scenes of repression, as well as moments of rebellion, unity, and hope.

These images have become new symbols for our generation. Statues of Chávez being toppled in different states and other powerful visuals deserve a place in future Venezuelan history books.

So far, over 20 deaths have been recorded during the protests (within one week), with the majority of victims being protesters at the hands of the country's police forces. These forces use various weapons (tear gas, rubber bullets, revolvers) and detain people for "incitement to hatred" taking them to different police stations. More than 1200 people have been arrested in a week, as confirmed by Nicolás Maduro himself.

Many of these detainees are arrested without a warrant, often arbitrarily—even in their own homes (in what's known as Operation "Tun-Tun" or "Knock-Knock" in english). They are held in secret, cut off from communication with their families, without shelter or food, and without even a trusted lawyer. But who will they accuse? Who will defend them? When all the institutional powers in Venezuela are controlled by Chavismo, it's an uphill battle.

Various NGOs provide assistance to these detainees, but securing their freedom is an arduous struggle.

The majority of detainees don't emerge from these experiences free, if they survive. It's well-known that the largest torture center in Latin America is located in Venezuela, called "El Helicoide." Detained protesters who exhibit "bad behavior" are taken there, to Caracas.

I won't delve into the specifics of El Helicoide and the various torture centers in my country because it's an incredibly sensitive topic that personally affects me deeply. However, I want to emphasize the subjectivity and arbitrariness of ending up in a place like that.

It all begins with the Law Against Hate, approved by Maduro in 2017, following months of protests in Venezuela. This law has led to multiple detentions, arrests, kidnappings, and violations of rights based on arbitrary and subjective considerations.

Peacefully protesting in the streets, posting anti-government images on your personal social media, reporting news unfavorable to the government in the media, or even a comedian making jokes about the government during a stand-up routine—all these expressions of discontent are censored and violated by the government.

I'm acutely aware of how this post might be perceived under that law.

And all of this stems from the infamous slogan "Here, we don't speak ill of Chávez" which persists in various government institutions to this day.

Now, what's next?

After providing all this context, it's a bit challenging for me to end this post with hope.

In the days following July 28th, tension filled the streets. If you needed supplies, you had to settle for whatever was available because panic buying had emptied the shelves. The brutal repression in the streets instilled fear among civilians.

Additionally, having even a simple anti-government image on your social media or phone can lead to persecution and detention. I'm not exaggerating. Currently, civilians have their phones searched arbitrarily by officials. If they find content against the government, it's grounds for arrest.

These days have been marked by anticipation, with an unsettling sense of "normalcy."

Many, like me, are just ordinary civilians who are simultaneously fearful and fueled by an inner fire after July 28th. We pretend to lead normal lives, fulfilling our daily responsibilities, but we can't erase what our eyes have seen and what we've lived through.

Traumatic flashbacks and memories are constant. Venezuelans exist in a perpetual state of physical and emotional stress. It's not victimization; it's a harsh reality.

Over time, you become used to it and even normalize this stress. You learn to live with it and overcome it until it becomes invisible. But then significant events like July 28th happen, and you remember that this isn't normal. You realize you don't live in an ordinary country. That's when all the repressed anger and frustration spill out.

On the other hand, I confess that before all this, I felt disappointed in myself. I didn't manage to register in the CNE to vote on July 28th. I carried the weight of disappointment from previous electoral processes, disillusionment with the opposition, and a sense of defeatism. And when I finally decided to register, I realized that the registration process had already closed.

I thought that this moment is unique and unrepeatable in our history, and I wouldn't be part of it simply because I didn't vote.

That feeling vanished in the days following July 28th when all the pent-up rage, frustration, and helplessness I had carried for years pushed me to the streets. It drove me to shout, bang pots at night, and support in any way I could.

That sensation disappeared when I realized that it's impossible not to be part of this. Whether you want to or not, you're affected by it, and if you care even a little about your country, it compels you to protest and contribute to the cause from your small corner, however you can.

Because I must acknowledge that, if this government has done anything right, it's uniting us all against it.

That's what's happening in Venezuela today.

My mom taught me, even before I was born, to love my country. She would lull me to sleep every day by singing "Venezuela", a beautiful composition created by two Spaniards. I grew up listening to that song, and every time I hear it, it fills me with more determination and strength to give my best, in any way I can, for my country. That's why I believe I speak for everyone when I say that we're all on edge because we know this can't remain as it is.

And it won't stay this way.

ESPAÑOL

Tengo varios días intentando escribir este post... Y es que últimamente no hago más nada que no sea sobre Venezuela. Mi país, mi hogar.

Las emociones no me daban para sentarme a pensar en ellas. Eso es lo que pasa cuando algo te duele mucho: enfrentarlo y hablar de ello, es un trabajo.

Pero aquí está:

Yo nací en el año 1998, año y mes en que también nació el caos que mi país vive hoy en día. No conozco otra cosa que no sea lo que estamos viviendo hoy. Jamás he vivido fuera, ni siquiera sé mucho cómo es la vida fuera de mi país, así que realmente esto es todo lo que conozco.

En 2002, 2014 y 2017, en Venezuela se desataron inmensas revueltas sociales, disturbios, que clamaban la voluntad del pueblo, básicamente: no queremos el chavismo - nombre de la ideología política del fallecido expresidente Hugo Chávez.

De todos esos años, el 2017 fue para mí (y para gran parte de mi generación) un año de inflexión. Fue el primer año en el que yo fui partícipe de las protestas, pacíficamente. Tenía unos 18-19 años, y viví aquella época como lo vive cualquiera que ama su hogar y lo quiere defender, y también lo viví como vive sus emociones cualquier adolescente ferviente; fue para mí -y para todos- un momento traumático y muy doloroso.

En aquella época, mi familia y yo pasamos meses despertando TODOS los días con el sonido de las bombas lacrimógenas. Las bombas y disparos empezaban muy temprano por la mañana. Y la verdad, con el pasar del tiempo, aunque ya los ruidos de afuera se me hacían familiares, nunca me acostumbré.

Mi casa en aquel entonces se ubicaba en un punto céntrico de la ciudad, donde se protestaba casi todos los días. Varias veces, al asomarme por las rejas de mi casa, veía las grandes tanquetas color verde militar fuera de mi residencia, y a los militares apuntando sus armas a mi calle residencial. Muchas veces, tiraban bombas lacrimógenas por encima de la reja de mi calle, y caían justo frente a mi casa.

Muchas veces, en mi casa nos encerrábamos en los cuartos, junto con mis perros que vivían bastante asustados, a esperar que todo pasara mientras llorábamos por efecto del gas lacrimógeno que inundaba todos los espacios de mi casa.

Esto no me lo contaron ni lo vi en un video en redes sociales, esto yo lo VIVÍ en carne propia durante meses, en el 2017. Y así como mi familia y yo, lo vivieron miles de venezolanos que tuvieron la suerte de sobrevivir aquella época, porque cabe acotar: muchos -muchos-, no.

En ese año, yo estudiaba en la universidad. Por obvias razones, todo el país -incluyendo la universidad- se detuvo, por meses. Sin embargo, la gente igual tenía que salir a trabajar, no podíamos estar meses totalmente detenidos. Así que, tal como ahora, en aquella época los negocios abrían en ciertos horarios, y la Universidad llamaba a la reincorporación a las aulas de manera contenida.

Debido a esto, era usual encontrarme durante las mañanas, mientras yo caminaba hacia la parada de bus que me llevaría a la Universidad, entre mis pies los casquillos de balas y de perdigones en el suelo, cientos de ellos. Incluso una vez guardé uno en mi bolso, para que nunca se me olvidara aquello que estaba viviendo.

Era prueba física e irrefutable de la brutal represión de la Guardia Nacional, porque aclaro para los que no son de Venezuela que quizá puedan estar leyendo esto: el porte libre de armas en este país es ilegal. Los únicos armados son los militares (y aquellos quienes el gobierno decide armar).

Por lo que, desde que empecé mi adultez, fui testigo de las injusticias y la violación de derechos que existen en mi país. Cabe destacar que esa no es la suerte de muchos, ya que ahora que estudio Medicina, he sido testigo de niños en el hospital que se preocupan cuando el médico le dice a su mamá que debe comprar equis cantidad de medicamentos e insumos, y me preguntan: "doctora, ¿cuánto cuesta eso y dónde mi mamá lo puede conseguir?"... ¿Es eso lógico, justo para un niño? ¿Es justo que un niño deba preocuparse por eso?

Ahora bien, ¿qué pasa hoy en Venezuela?

Bien, creo que gran parte del mundo sabe lo que está pasando: una rebelión civil contra el gobierno de Nicolás Maduro, debido a su nueva proclamación como Presidente de la República.

El 29 de Julio del 2024, a las 12:09 a.m., toda Venezuela se enteraría de la nueva reelección totalmente arbitraria de Maduro, luego de que la mayoría de la población venezolana electora saliera a votar desde la madrugada del 28 de Julio, casi el 70% por Edmundo González Urrutia, el candidato de la oposición liderada por María Corina Machado.

Esta última, fue realmente la elegida por la mayoría de los venezolanos en unas elecciones primarias rumbo a las presidenciales, pero para sorpresa de nadie, el régimen actual la inhabilitó políticamente, por lo que María Corina terminó -luego de varios intentos- encabezando la candidatura a través del nombre e imagen de Edmundo González, quien ya estaba inscrito de manera independiente, por lo que el Gobierno no pudo inhabilitarlo a él también.

La pregunta que muchos pueden hacerse es:

¿Cómo estamos seguros de que en las elecciones presidenciales del 28 de Julio se cometió fraude electoral?

Bien, aparte de opiniones y perspectivas personales que yo y la mayoría de los venezolanos vivimos en el día a día -donde es difícil conseguir a alguien contento con el actual gobierno por la calle- la oposición ha publicado las actas originales, autentificadas por sus códigos QR -que indican que dicha acta fue emitida por una máquina de votación -, que muestran cada uno de los votos de todos los venezolanos, en todos los estados del país. Esto fue publicado a través de una página web que diseñó la oposición, previendo el fraude.

El resultado fue bastante claro: los venezolanos escogieron al candidato opositor, Edmundo González, como nuevo presidente de Venezuela, con una aplastante mayoría del 67% en contraste con el 30% de Maduro, y el restante distribuido entre el resto de candidatos.

¿En qué resultó todo esto?

Desde la madrugada del 29 de Julio, se desataron protestas no convocadas por la oposición, sino reflejo del descontento del pueblo venezolano.

¿Por qué?

Porque todos sabemos lo que pasó. Todos lo vivimos.

La tarde del 28 de Julio yo me dirigí a mi centro de votación más cercano para el escrutinio de los votos de ese centro, y así como yo, muchos venezolanos hicieron lo mismo en diferentes centros. Y en la inmensa mayoría jamás había ganado Maduro, a excepción de pocas parroquias en algunos estados del país.

Se difundieron por las redes sociales diferentes videos con el conteo real de los votos de cada centro, y en ninguno proclamaban a Maduro vencedor. Pero más allá de percepciones personales y videos de redes sociales: las actas están, y prueban lo que aquí digo.

Este fraude desató, aparte de las protestas, una represión brutal en las calles. Era de esperarse, de hecho, todos lo esperábamos aunque no lo queríamos.

¿Cómo se vivieron los días antes del 28J?

Con ansiedad y expectativa. Eso se vio reflejado en las calles, sobre todo en los mercados.

El sábado en la noche, justo antes del fatídico día domingo, algunos mercados eran una locura: repletos de gente haciendo compras nerviosas, las neveras de carne y charcutería vacías, las estanterías de productos de la cesta básica casi vacíos... Ya todos teníamos previsto lo que podía pasar; y es que, lamentablemente, no es la primera vez.

Hace unas semanas, conversando con una amiga inglesa que quería quedarse en el país durante las elecciones presidenciales, me decía que le emocionaba este evento porque ella sabía que no eran unas elecciones cualquiera, en sus propias palabras: "nunca sabes qué puede pasar aquí". Y era así, tal cual: luego del 28 de Julio, había un gran signo de interrogación.

Los planes que hacíamos para la semana después del 28 de Julio, no eran definitivos. Todos al final decíamos "bueno, depende de lo que pase".

En mi opinión, habían, básicamente, tres caminos:

- El más probable: protestas masivas y represión brutal si el CNE (Consejo Nacional Electoral) proclamaba como ganador a Maduro.

- Alegría intensa (y quizá tensa) si ganaba la oposición.

- Que nada pasara, independientemente del resultado (como en anteriores oportunidades, donde existía una sensación de indiferencia colectiva).

Por supuesto, yo anhelaba el segundo camino, pero sabía que el primero era el más probable.

Luego de la proclamación de Maduro, un sentimiento desconcertado de desasosiego y desilusión, inundó todo el país. Esto, inevitable y justificadamente, derivó en protestas totalmente espontáneas.

Las redes sociales se llenaron de imágenes de manifestantes en las calles de todo el país, y con ello, imágenes brutales y terroríficas de la represión, así como algunas de rebelión, unión y esperanza, que ahora son nuevos símbolos para esta generación.

Imágenes de estatuas de Chávez siendo derribadas en diferentes estados, y demás imágenes que merecen ser portada de futuros libros de Historia de Venezuela.

Hasta ahora, se han registrado más de 20 fallecidos en el marco de las protestas (en 1 semana), la gran mayoría de estas siendo de manifestantes en manos de los cuerpos policiales del país que salen a reprimir con diferentes armas (bombas lacrimógenas, perdigones, revólveres), quienes además se llevan a las personas por "incitación al odio" y los detienen en las diferentes sedes policiales.

Se han registrado más de 1200 detenidos, en una semana, admitidos por el propio Nicolás Maduro.

A muchas de estas personas las detienen sin una orden, de forma totalmente arbitraria incluso en sus hogares (la llamada Operación Tun-Tun). Los mantienen en la clandestinidad, sin comunicación con sus familias, sin abrigo o comida, sin siquiera un abogado de confianza. ¿Y con quién los vas a acusar? ¿Quién te va a defender? Si todos los Poderes institucionales de Venezuela están regidos por el chavismo.

Hay diversas ONG que brindan ayuda a estos detenidos, sin embargo, se trata de una lucha ardua para lograr la libertad de ellos.

La mayoría de detenidos, no salen libres de estas experiencias, si sobreviven. Es bien sabido que el más grande centro de tortura de Latinoamérica, se encuentra en Venezuela, llamado El Helicoide. A los manifestantes detenidos que tienen "un mal comportamiento", se los llevan para allá, a Caracas.

No hablaremos del Helicoide y diferentes centros de tortura que existen en mi país, porque realmente es un tema muy sensible y que personalmente me afecta mucho. Sin embargo, quisiera resaltar de este punto particular, lo subjetivo y arbitrario que es terminar en un sitio como este.

Todo empieza por la "Ley de Incitación al Odio", aprobada por Maduro en 2017, a raíz de los meses de protestas que acontecieron en Venezuela en ese entonces. Esta ley ha resultado en múltiples detenciones, arrestos, secuestros y violaciones de derechos, a partir de consideraciones arbitrarias y subjetivas.

Protestar pacíficamente en la calle, subir una imagen en contra del gobierno a tus redes sociales personales, informar noticias no muy beneficiosas para la imagen del gobierno en medios de comunicación, e incluso que un comediante haga chistes del gobierno en su rutina de stand-up. Todas estas manifestaciones de descontento, son censuradas y violadas por el gobierno.

Incluso, estoy bastante consciente de cómo puede ser tomado este post, bajo dicha ley.

Y todo esto, a raíz del famoso "Aquí no se habla mal de Chávez" que surgió en su época, eslogan que pinta, aún a día de hoy, diversas instituciones del gobierno.

¿Y ahora, qué?

Pues bien, luego de darles todo este contexto, me resulta un poco difícil terminar este post con esperanza.

Los días posteriores al 28J, había una inmensa tensión en las calles. Si necesitabas comprar insumos, debías conformarte con lo que te vendían, porque durante unos días era difícil conseguir exactamente lo que tú deseabas comprar, debido a que todo el país se paralizó y las compras nerviosas arrasaron con los anaqueles.

La brutal represión en las calles, era y es motivo de miedo entre la población civil. Sumando que, a día de hoy, tener incluso una simple imagen contra el gobierno en tus redes sociales o en tu teléfono, es motivo de persecusión y detención. Y no, no estoy exagerando. Actualmente, hay casos de civiles a quienes les es revisado su teléfono en las calles, por parte de funcionarios, y de nuevo, de forma totalmente arbitraria. Si te consiguen contenido contra el gobierno, es motivo de detención.

Estos días se han vivido, de nuevo, en expectativa. Con una sensación inquietante de "normalidad".

Algunos, como yo, siendo una simple civil más, con cierto temor y a la vez cierto fuego por dentro. Fingiendo una vida normal, cumpliendo con las responsabilidades del día a día, pero no se me borran de la mente todo lo que mis ojos han visto y todo lo que hemos vivido.

Los flashbacks y los recuerdos, algo traumáticos, son constantes. Los venezolanos vivimos en un constante estrés físico y emocional. No es victimización, es totalmente real.

Estrés al que, con el tiempo, te acostumbras y normalizas. De hecho, aprendes a vivir con ello y superarlo, hasta el punto en el que se hace invisible. Pero luego, suceden eventos importantes como el 28J, y recuerdas que no es para nada normal. Recuerdas que no vives en un país normal. Es allí cuando toda la rabia y frustración reprimida, se puso en manifiesto afuera.

Por otro lado, yo confieso que, antes de todo esto me sentía mal conmigo misma, y es que no alcancé a inscribirme en el CNE para votar el 28J. Venía con una gran decepción a raíz de todos los procesos electorales anteriores, una gran decepción con la misma oposición y una gran sensación de derrotismo. Y cuando por fin me animé a hacerlo, me enteré de que el proceso de inscripción ya había vencido.

Llegué a pensar que este es un momento único e irrepetible en nuestra historia, del cual yo no iba a formar parte por el hecho de no haber votado. Esta sensación desapareció con los días posteriores al 28J, cuando toda esa rabia, frustración e impotencia contenida que había guardado desde hace años, me empujó a la calle. Me empujó a gritar, cacerolear, apoyar de cualquier forma que pudiese.

Esa sensación desapareció en el momento en el que me di cuenta que es imposible no formar parte de esto. Quieras o no, te ves afectado por esto y, si quieres al menos un poco a tu país, eso te empuja a protestar y ayudar a la causa desde tu pequeño rincón, sea como sea.

Porque debo reconocer que, si algo ha hecho bien este gobierno, ha sido unirnos a todos contra él.

Eso es lo que está pasando hoy en día en Venezuela.

Mi mamá me enseñó, incluso antes de nacer, a querer a mi país. Me arrullaba todos los días cantándome "Venezuela", una composición preciosa hecha por dos españoles. Crecí escuchando esa canción y cada que la oigo, más ganas y fuerzas me da para dar lo mejor de mí, de cualquier forma que pueda, por mi país. Razón por la cual creo que hablo por todos cuando digo que, en definitiva, todos estamos a la expectativa, porque sabemos que esto no se puede quedar así.

Y no se va a quedar así.

We are living through a challenging period in history. The world is facing a crisis with its nuances, and Venezuela’s crisis is a result of perpetual caudillismo. I do not want to hand the country over to Chavismo. My rejection is irreconcilable. Your text made me feel powerless, not because it was poorly written, but because it reminds me of the kind of country we live in. We must not forget it. We must not normalize it. LY.

!discovery 35

gracias 🤍

This post was shared and voted inside the discord by the curators team of discovery-it

Join our Community and follow our Curation Trail

Discovery-it is also a Witness, vote for us here

Delegate to us for passive income. Check our 80% fee-back Program