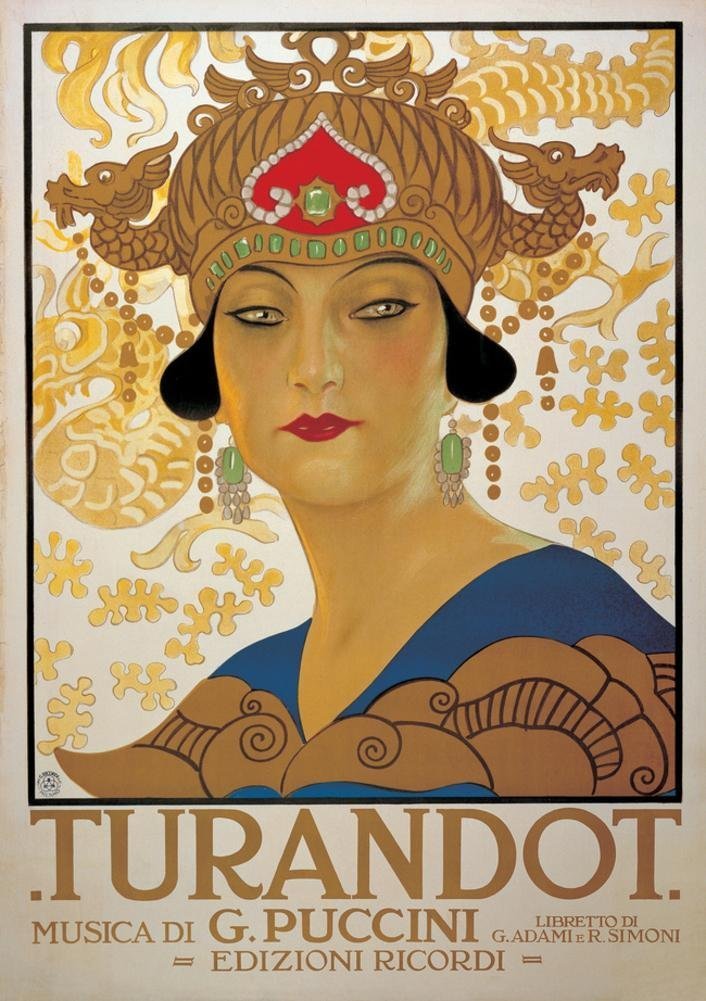

I decided to generate twelve opera films reviews representing my twelve favorite operas (without any claim of these also being the twelve greatest). Don't hold your breath waiting for Wagner to make an appearance. My list will include predominately Italian operas, with two or three Russian ones, one from France, and one or two still to be determined. My series opens here with the final masterpiece of Puccini, first performed in the La Scala Opera House in Milan, April 25th, 1926.

source

Historical Background

Giacomo Puccini was born December 22nd, 1858, descending from a long line of musicians who enjoyed strong, if local, reputations, mainly in the domain of sacred music. Puccin's father, however, played little role in his musical education, since he died while Giacomo was still just a child. Puccini nevertheless developed his musical talent so well that he was sent to the Milan Conservatory at the expense of an affluent relative as well as the Queen of Italy. There he attracted the attention of Amilcare Ponchielli, who persuaded Puccini to try his hand at a one-act opera for competition. Though Puccini's entry, Le Villi (1884), was overshadowed by an entry written by Pietro Mascagni (Cavelleria Rusticana, now one of the staples of the operatic repertoire), it drew the attention of the powerful music publisher, Giulio Ricordi, and Puccini was on his way to a remarkable career. It was not until his third opera, Manon Lescaut (1893), that Puccini's talent gained international recognition. He followed that success with a string of three great operas that rank among the most beloved ever composed: La Bohème (1896), Tosca (1900), and Madame Butterfly (1904). La Bohème is Puccini's most renowned work and Tosca the most remarkable theatrical tour de force, but there's no telling what Puccini might have produced had he not died at just sixty-six years of age. There's no telling – except that we can derive some inkling as to the direction that his creative talent was taking by considering the magnificent work with which he closed out his life: Turandot, published posthumously, two years after his death in 1926. In some respects, it is his greatest masterpiece.

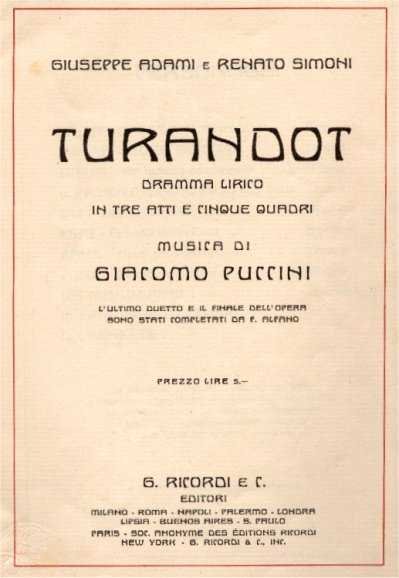

Puccini was not an especially fast worker but there was also the problem in finding suitable librettos. After Madame Butterfly in 1904, Puccini had completed just three opera during the next fourteen years, for the aforementioned reasons as well as the distraction of World War I. After Il Tritico (a triptych of three one-act operas) was published in 1918, Puccini again found himself delayed by the search for a good libretto and, this time, the delay proved costly. While working on Turandot, Puccini grew ill and died on November 29th, 1924, in what was expected to be a survivable operation for throat cancer. Turandot had been completed except for the final duet and the refinements that Puccini was in the habit of making for all of his operas right up to their respective premières. Turandot was "completed" by one of Puccini's talented pupils, Frederico Alfano, and quite respectably so, though one has to wonder how the master would have brought his great opera to conclusion.

source

Letters written by Puccini while he was working on Turandot make it clear that he intended Turandot to be something of a capstone on his career as a composer. Puccini worked closely with the two librettists, Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni, to create the libretto that would support his ambitious plans for Turondot. The libretto was based on a play by Carlo Gozzi (Turandotte), but it is fairer to say that the opera was "inspired by" the play than an adaptation of it. Puccini's first demand was for the libretto to have some real epic breadth, but the serious element had to be complemented by some comic relief. Gozzi's play provided four comic characters. Under Puccini's instructions, Adami and Simoni reduced the four to three (Ping, Pang, and Pong), but also gave them deeper philosophical undertones and ambivalence. Puccini's creative muse required another modification, as well. Puccini's inspiration had always depended most especially on a passionately romantic quality in his librettos, typically in the form of a fragile female who perishes tragically for love (such as Mimi in La Bohème). Gozzi's play provided no such romantic quality, so the character we now know as Liù was added. The addition of Liù to the plot deepens the entire content of the story. In both the play and the opera, the ice princess, Turandot, learns the meaning of love, but only in the opera does she learn it through the example of the self-sacrifice of a pure-hearted and devoted slave girl.

The Story

Turandot is an opera in three acts, based on a "fiaba" by Gozzi. In Peking, in legendary times, Princess Turandot has thrown down the gauntlet.

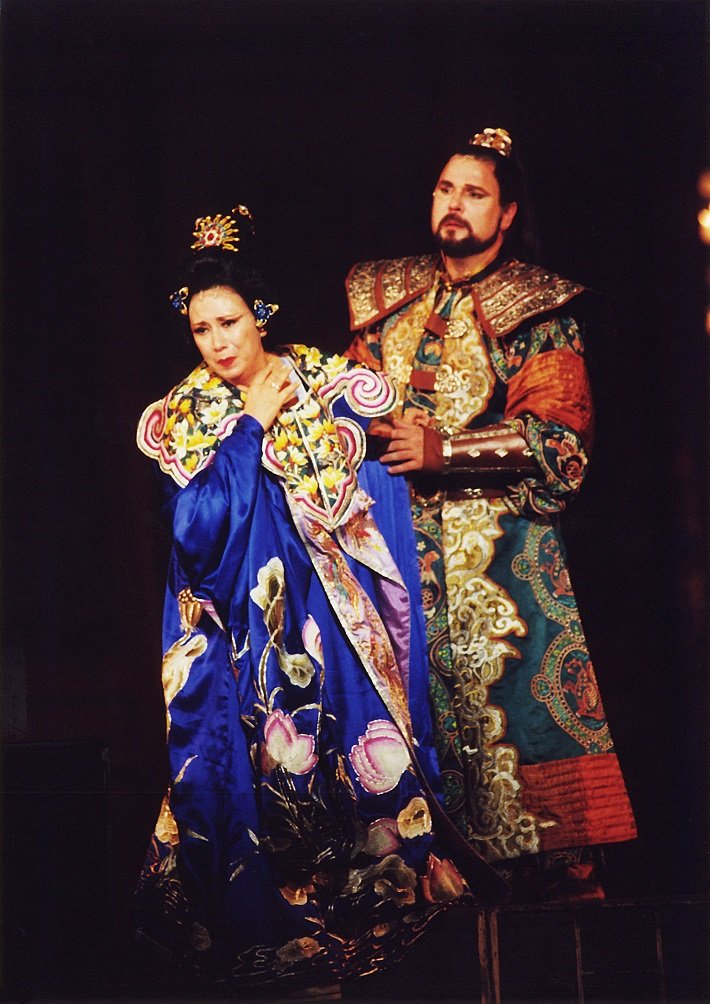

The last to fail at the test, a Prince of Persia, is to be beheaded when the sun rises. Meanwhile, in the town square, a simple slave girl, Liù (Barbara Frittoli), struggles to help her elderly master, the exiled and destitute King Timur (Carlo Colombara), who has fallen to the ground. A young man, Calaf (Sergej Larin), comes to her aid, only to discover that the elderly man is his father, for whom he has been searching for years. Their joyous reunion is short lived, however, as the rising sun brings with it the execution march. For his part, Calaf bemoans the cruelty of a woman who would send a handsome, young man to his death – until, that is, he spies the beautiful and chaste Turandot (Giovanna Casolla) with his own eyes. Calaf is thunderstruck and realizes immediately that his destiny lies in accepting the challenge of the riddles in pursuit of Turandot's love. Liù, who has loved Calaf devotedly ever since he once smiled upon her, pleads with him not to throw away his life. Neither her entreaties nor the simple good sense offered by three merchants, Ping (Joeé Fardilha), Pang (Francesco Piccoli), and Pong (Carlo Allemano), can dissuade the hot-blooded Calaf, who has lost all reason to love. Act I comes to a crashing conclusion as Calaf strikes a giant gong that signals his intent to undertake the challenge.

Act II opens on a pavilion occupied by the booths of Ping, Pang, and Pong and surrounded by curtains embellished with Chinese figures. The three merchants are sensibly planning inventory appropriate for either contingency: a wedding or another burial. Their discussion of practicalities is interlaced with reminiscences of more peaceful times and places, such as a little pond of blue, a bamboo forest, and a Chinese garden. The crowd begins to gather for Calaf's trial by riddle, presided over by Turandot's father, the Emperor Altoum (Aldo Bottion), seated on a magnificent throne of gold.

Well, Calaf finds the answer to all three, though struggling a bit with the last one, for dramatic effect. The Princess is mortified and terrified and wants to weasel out of the contest's stipulations. She is still a man-hater and is repulsed by the thought of submitting to this stranger. Neither the Emperor nor the crowd will let her off the hook, but the noble Calaf wants her love, not merely her submission. He offers her one riddle in return. If she can solve it by dawn, he will surrender his life to the headsman. She must determine his name before the sun rises.

Act III begins with all of Peking frantically trying to discover the stranger's name, by order of Turandot and at penalty of death if they fail. No one knows his name, of course – except, Timur and Liù. Good old Liù, good sweet, devoted Liù, states that only she knows the stranger's name to protect her master, Timur. Liù is tortured by Turandot's guards, but reveals nothing. Finally, fearing that she will weaken, Liù seizes a dagger and stabs herself to death. The crowd and Turandot are moved by this demonstration of love and devotion by Liù and as the sun is about to rise, it seems that Calaf has triumphed. Calaf takes Turandot into his arms and kisses her. He senses an awakening of warmth and passion in her. Calaf decides to gamble all on the hope of gaining a consenting partner, hopeful that Turandot will choose love over hatred.

Themes

The principal theme of this film is that Love is the light of the world and its inverse corollary, Hatred is the darkness of the world, especially indiscriminate hatred. Throughout most of the story, Turandot epitomizes indiscriminate hatred as she herself expresses in Act II, Scene 2.

Turandot has become a man-hater because a man once committed a great crime against her ancestress. In her mindset, the villain was "a man like you" – like very other man. Turandot's single-minded prejudice becomes all the more meaningful when we realize that she represents not only herself as an individual but, as a princess, her state.

The generalization of hatred from a wrongful individual to that individual's group is what perpetuates the cycles of violence that have plagued mankind throughout history. It is understandable that Turandot might hate the man who abducted her ancestor, but he is long gone and it makes no rational sense to hate all men for the actions of that one. Hate the neighborhood kid who bullied you when you were young, if you must, but don't hate all who happen to be of the same race or ethnicity.Turandot argues: let love replace irrational generalized hatred.

Production Values

The evaluation of an opera libretto is subject to somewhat different criteria than the script for a typical film. There is still the issue of the quality of the story, but opera stories are generally expected to be highly melodramatic. It is equally or more important that an opera libretto provide an opportunity for great music. In that latter respect, the libretto for Turandot is sensational. This was the first opera in which Puccini successfully treated the chorus as another protagonist, rather than mere musical accompaniment. Moreover, the libretto allowed Puccini to seamlessly integrate solo arias, duets, trios, and various choral groups into an unbroken flow of sublime music. There is very little recitative in Turandot. The opening act, in particular, is one of the most amazingly constructed segments in any opera. Consider what transpires in that one Act! A prince finds his father traveling in exile after many years of searching for him, another prince is beheaded, all of the main characters are not only introduced but their respective natures substantially revealed, the protagonist spies the love of his life, and the story's chief conflict is set dramatically into motion by the striking of a giant gong, as the Act ends. That's more than gets accomplished in the plotlines of many entire films.

The character Timur may have been based on Abdallah Es-Zaghal, a Moorish king of Grenada, who sold his kingdom for a fortune. He was then arrested and blinded by Benimeren, the King of Fez, who stole his wealth and forced King Abdallah to live thereafter as a panhandler wearing a sign that read, This is the unfortunate kind of Andalusia.

Viewed simply as a romance, there are plot holes in the story of Turandot big enough for all 250 acres of the Forbidden City to pass through. Love in China, it would seem, is of the shallowest variety. Liù falls eternally in love with Calaf based on a single smile while Calaf loses all reason after having spied Turandot just once from a distance, notwithstanding her cruelty and icy demeanor. Calaf remains devoted to Turandot even after his father's faithful servant is tortured. It takes Liù's martyrdom to kindle the first spark of love in Turandot. Personally, I'd choose a less complicated woman! The script makes more sense viewed as allegorical of the hatred of one people for another and the power of martyrdom as a demonstration of human capacity for love and forgiveness.

The plot of Turandot follows a long tradition of myths incorporating riddles, such as the Sphinx's riddle in the Oedipus legend: What is it that walks on four legs in the morning, two at noon, and three in the evening? Hint: the third leg is a cane! You figure it out from there! The riddles in Turandot are skillfully constructed and challenging and the stakes are high – very high, as one can presume that the severed heads of the losers are indeed set out on high stakes. Turandot's beastly riddles had already claimed twenty-six lives before Calaf took his shot.

The production values for this opera film are without precedence. The colorful, authentic imperial-era costumes and incomparably lush sets together with the unique setting within the great Forbidden City make this opera event a special occasion indeed. The staging of the extravaganza was magnificent, using hundreds of extras strewn across a massive stage. Musically, Zubin Mehta conducts the production brilliantly. The soloists are strong and the choruses well prepared. The choreography is exceptional as well. The greatest of all Chinese film directors, Zhang Yimou, was enlisted to create the film out of the special performance in the Forbidden City. Zhang provided much more than a mere taping of a live performance. He integrated dissolve shots of gorgeous scenic locales from around China (where the dialog alludes to such) and occasional double exposures to produce a real cinematic experience. The production itself was filmed from a variety of angles and shot distances and Zhang has masterfully edited the film to provide ample variety. Many of you will remember Zhang from such cinematic masterpieces as Raise the Red Lantern (1991) and Hero (2002). Most of you will acknowledge that Zhang has not disappointed you in the past and he's not going to disappoint you here, either. I own another filmed version of Turandot, with the great Metropolitan Opera, which is musically just as good as Zhang's version, but can't compare in the brilliance of the production.

Sergej Larin is one of the world's leading tenors. He made his international debut in Vienna in Eugene Onegin and his American debut at the San Francisco Opera in 1992 in Tosca. He is a Russian native who studied at the Lithuanian National Convervatory in Vilnius. His appearances in opera recordings include Boris Godunov (as Dimitri) and Mazeppa (as Andrei). His performance in Turandot as Calaf was impeccable. Giovanna Casolla, who played Turandot, began siging opera in Milan in 1982 in Puccini's Il Tabarro. She has been a regular guest performer in opera houses throughout Italy and around the world, including Vienna, Munich, Brussels, Buenos Aires, and Tokyo. Her outstanding performances in 1996 at the Grand Théâtre in Geneva, the Orange Festival in 1997, and the Puccini Festival at Torre del Lago in 1998 earned her the invitation to play Turandot in the Forbidden City. Barbara Frittoli gave a fabulous rendition of Liù. She has appeared in filmed television versions of Falsaff (twice), Othello, and Cosi fan tutte. Fardilha, Piccoli, and Allemano were outstanding in the important secondary roles of Ping, Pang, and Pong.

For lovers of opera, my enthusiastic recommendation of this magnificent rendition of Turandot is an easy call. This particular production and this particular opera will pose less of a test of the patience of those not used to opera than most any other opera film. There's plenty of color, motion, passion, and gorgeous music. The relative lack of recitative keeps the impassioned music flowing on an almost continuous basis.

Wow good review!