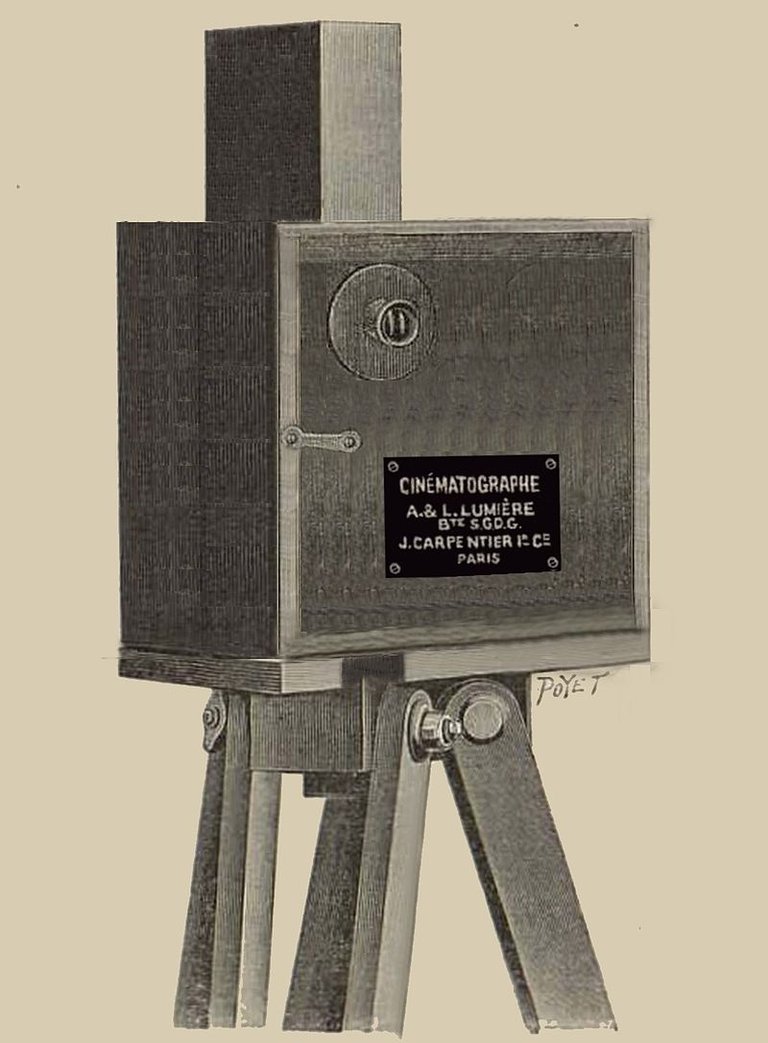

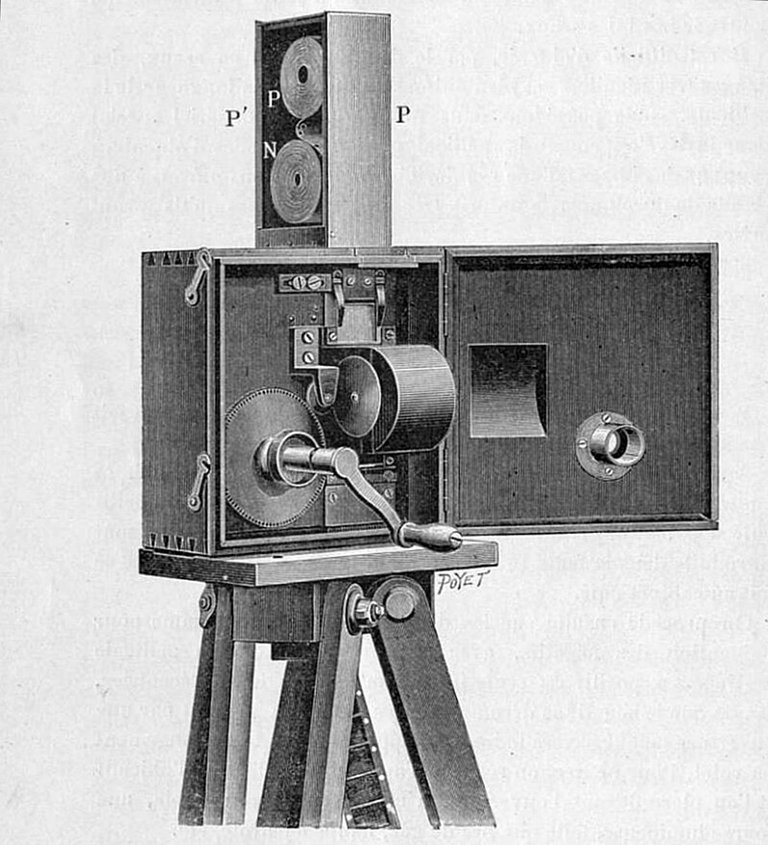

Louis Lumière, a prominent French industrialist and engineer, patented on February 13, 1895 the device that would serve both for obtaining and projecting photographic images, or in the language of the time, “chronophotographic”. On December 28 of the same year, he would carry out the first really successful public projections. Louis Lumière called his invention “cinematograph”, a name that refers to movement and that we continue to use to this day. Although his brother Auguste is also mentioned in the patent, some historians consider Louis the true inventor.

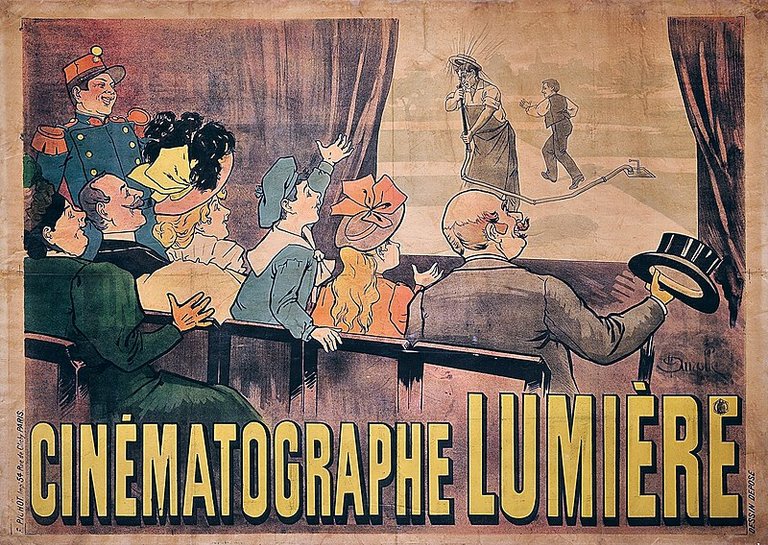

That first public screening, and those that followed, held at the Salon Indien of the Grand Café, at 14 Boulevard des Capucins, made a deep impression on Parisians, who on successive days came again and again to the hall to watch the miracle. At each session, 10 short films were shown, with a total running time of between 20 and 25 minutes.

As new spectators arrived, Louis Lumière commissioned his operators to make new films of the everyday events that were being filmed every day.

What was the reason for the great success of Louis Lumière's apparatus, what differentiated his films from what other filmmakers were doing with more or less success? First of all, the technical quality of his films. This quality is not to be sought in the cinematographic language, which did not yet exist as such, but in the sharpness of his images and the fluidity of the movements captured, which, despite the black and white of what was projected on the screen, produced a singular sensation of life never seen before. The anecdote of the effect produced by the short film “Arrival of a train at the station” is well known: many spectators left their chairs in fear when they saw the machine rushing towards them.

That reaction may seem exaggerated and laughable to us now, but we must put ourselves in the shoes of those people who saw for the first time a photograph come to life before their eyes in the form of a menacing locomotive. The boundaries between life and cinematographic fiction were not yet very clear or defined.

Lumière's cinematograph was simple and of great technical perfection; an easy to operate apparatus that served to take the views and to project them. In fact, as news of the marvelous invention spread through Paris, Louis Lumière sent his operators to capture the day-to-day life of the city, and a few hours later these newly captured images were shown in the theater. The sensation was so great that sometimes the operators would manipulate their apparatus without film, pretending to record reality, and the spectators would come to the performances looking to find themselves on the screen. Which, in fact, occasionally happened.

As we have already said, Lumière's films presented everyday situations: the aforementioned arrival of the train, a baby's bath, the departure of workers from a factory, the demolition of a wall, a card game, a children's fight. It could be said that they had an eminently documentary vocation, or, if you prefer, a record of reality. However, that same year a different one was exhibited, “The irrigator watered”, of which another version was made in 1896. The anecdote is taken from one of the first newspaper comics: a gardener waters some plants and a child (in the first version; an adult in the second) crushes the hose, preventing the water from flowing out. When the gardener brings the mouth of the hose close to his face, the other character allows the water to circulate again, watering the gardener.

In this very small film of forty seconds we already find the potential of great fiction films. A potential that, curiously, Louis Lumiére did not know how to see.

In his justly famous film “The Arrival of a Train at the Station”, the basic elements of what would later become the language of cinema are condensed in a single fixed shot. Although it is true that in an unintentional way. This is the film that frightened its viewers. In the first seconds we see a locomotive approaching while several people and employees wait on the platform. As the train approaches and stops and the passengers disembark we have several shots: general shot of the station and the platform; close-up of the people waiting; then we see many people entering and leaving the field of view in medium, American and close-up shots. Or, in other words: the general landscape, with the people in full body; the people at half-length, a little above the knees and at head height. Of course, by 1895 these shots were unnamed.

The essential grammar of cinema had not yet been invented. As we will see on another occasion, the nascent novelty forgot for several years this discovery, which turned out to be premature, but which bore abundant fruit a short time later.

Note: as English is not my mother tongue, I have used Deepl to translate the text.