Rates are anticipating a trend that many are ignoring

These days, the financial media are focusing on an indicator that has been in vogue since the beginning of the pandemic: the rate curve, i.e. the curve expressing the difference between the interest rates of 2-year and 10-year US bonds.

Normally, short-term bonds, being less risky, have lower interest rates than long-term ones.

However, when these bonds start to behave unusually, offering higher interest rates than long-term bonds (i.e. when the rate curve starts to flatten), it is a sign that investors expect a recession within the maturity period of these bonds.

As the rate curve has started to reduce its usual slope in recent weeks (although it has not yet flattened out), many analysts are already beginning to speculate that the bond market is anticipating a possible recession in the medium term, i.e. during the life cycle of sub-3-year bonds.

In this article, we are not discussing whether a recession in the US will actually occur, but rather we will try to correct some misreadings of the bond market that may prevent investors from making the right decisions in the coming weeks.

The first suggestion I would share in this respect is not to focus too much on the rate curve.

Why the yield curve is not reliable

The reason is that the Federal Reserve's monetary policies have irretrievably compromised the reliability of this indicator.

The central bank's excessive liquidity issuance over the past two years has actually manipulated the short-term side of this indicator, i.e. the 2-year bond rates, downwards.

On the other hand, the Fed's decades-long policy of buying back bonds has also compressed the upward trend in long-term rates.

And although the Fed has now decided to put a brake, at least temporarily, on these policies, this will not be enough to correct these distortions.

In fact, even if the Fed starts to make all the increases in short-term rates it has promised, thus triggering a rise in the short-term side of the indicator, its programme of slowing purchases of long-term government bonds will cause long-term rates to rise as well.

In the end then, the relationship between short-term and long-term rates would remain the same.

The interest rate curve would not flatten out at all, except perhaps for a short time and only for contingent reasons, due to the imperfect coincidence in time between interest rate increases and the reduction in bond purchases.

Having therefore abandoned this indicator, my second suggestion is to focus on the bond market in its entirety.

It is only by widening the field of vision to all sectors of this market that we can see a significant inconsistency that is currently escaping the financial media.

What is it?

The only useful signal the bond market is giving us

All the media have rightly highlighted the rapid rise in interest rates on US government bonds following the Fed's announcement of possible rate hikes.

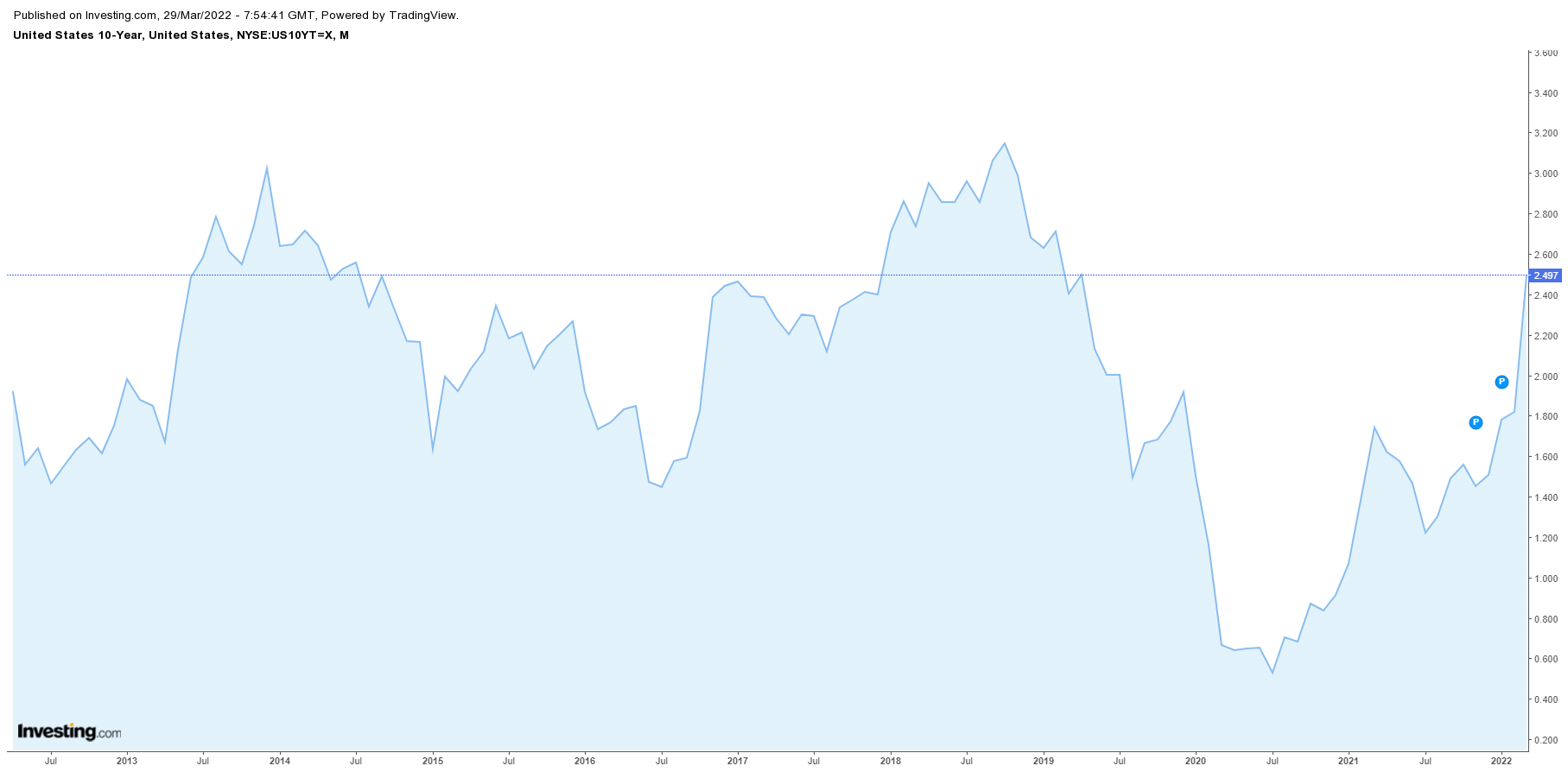

For example, here we see that the 10-year US government bond is about to reach historically high yield levels:

The same rise in yields is also happening in "corporate" bonds, i.e. bonds issued by private companies, but only in the "investment grade" sector, i.e. for those companies with a low risk of default.

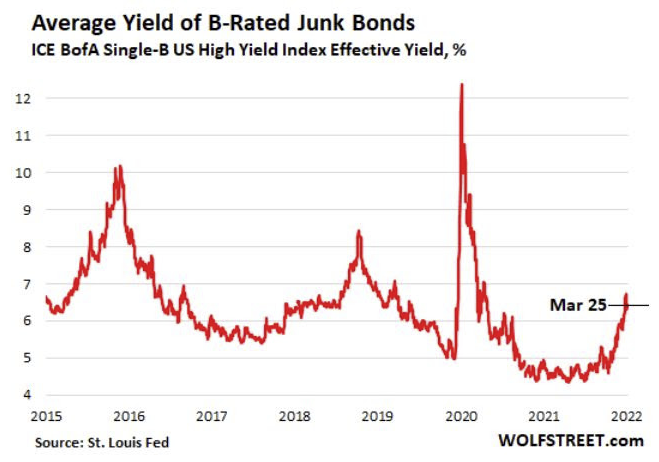

If, on the other hand, we look at yields on high yield corporate bonds, i.e. bonds issued by companies with a high risk of default, we see that yields have risen very little:

High yield bond rates represent investors' propensity to enter the riskier sectors of the market, both stocks and bonds.

The lower the rates are, the more investors appear unconcerned about the default risks of these companies.

The weak rise in these rates therefore indicates that investors, despite inflation, the Fed's restrictive monetary policies and the war, are still well disposed towards the most profitable sectors of the stock markets. They are just waiting for the best time to get back in.

What this means in practice

The conclusion of our discussion is that if we tried to understand the direction of the markets on the basis of the rate curve examined at the beginning, our reading would be distorted.

Certainly, the feeling that the US economy may soon enter a recession is correct. And it is confirmed by other data that we have discussed in previous articles.

The misinformation given to us by that indicator is rather that investors in the bond market are showing defensive behaviour because of the prospects of recession.

If we look at the bond market as a whole, the opposite is true.

Stock markets seem ready to enter a medium-term bullish phase, despite the current negative economic, political and social conditions and the prospect of a recession.

Many analyses focusing on stock market capital flows agree with this hypothesis.

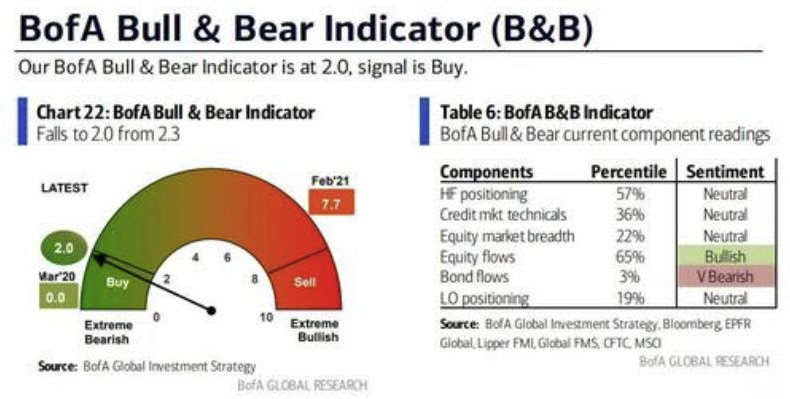

By way of example, here is what Bank of America's indicator, which summarises various market components, including capital flows, indicates:

As you can see, the conditions indicating an extreme "oversold" phase (we use this term for simplicity, although it is improper on this indicator) have reached a level considered very "bullish".

The reasons for this apparent inconsistency between the negative situation we find ourselves in and the bullish outlook for stock markets, especially in high-growth sectors, are varied and will be addressed in future articles.

Thanks for reading.

Posted Using LeoFinance Beta

If that is the case why does the LIBOR yield curve tell us the same thing? Has the Fed been buying long term LIBOR futures? Do you see those on the Fed's balance sheet? No you do not.

The LIBOR started to invert back at the beginning in December, before the Fed even announced its rate hikes.

So therefore I think you analysis is just spewing more of the myths that so many promote. The yield curve (both) is clearly stating that growth and inflation expectations are not what everyone is proclaiming.

Posted Using LeoFinance Beta

The article does not deal with a possible recession but with the flattening of bond yield rates and why they cannot be considered individually as a tool to predict a possible crisis.

As far as LIBOR is concerned, the expectation of increasing and exogenous inflation (therefore not deriving from economic growth but from the scarcity of raw materials caused by COVID and the restart of industry) positively influences the rate which, as I recall, is influenced by monetary policies (interest rate increases) but also by inflation, while it is not influenced and cannot be manipulated through futures. I think you should find out more about how it is set. By the way, LIBOR is not a reliable parameter since 2008, it will be soon replaced and it concerns the international panorama, so I don't understand why it should be taken into consideration within my analysis.

I thank you for your comment.

Yay! 🤗

Your content has been boosted with Ecency Points, by @cryptomaster5.

Use Ecency daily to boost your growth on platform!

Support Ecency

Vote for new Proposal

Delegate HP and earn more

Congratulations @cryptomaster5! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s):

Your next target is to reach 4750 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCheck out the last post from @hivebuzz:

Support the HiveBuzz project. Vote for our proposal!