The concept of money always fascinated me. Money is the tool that allowed mankind to avoid the inconvenience of bartering. Money serves its purpose by having a value that is shared and accepted by the community that uses it. The more universally accepted is its value, the better.

Thus, the use of precious metals as currency is straightforward. Precious metals are scarce, they do not deprecate over time and their intrinsic value is known from the beginning of civilisation. Gold and silver will unquestionably remain the quintessential currency mankind will ever need.

If we have gold and silver, why ever paper-money? Well, convenience! Essentially the first bonds and later the first banknotes were introduced to the market with the guarantee of paying the bearer the amount of precious metal promised on the piece of paper.

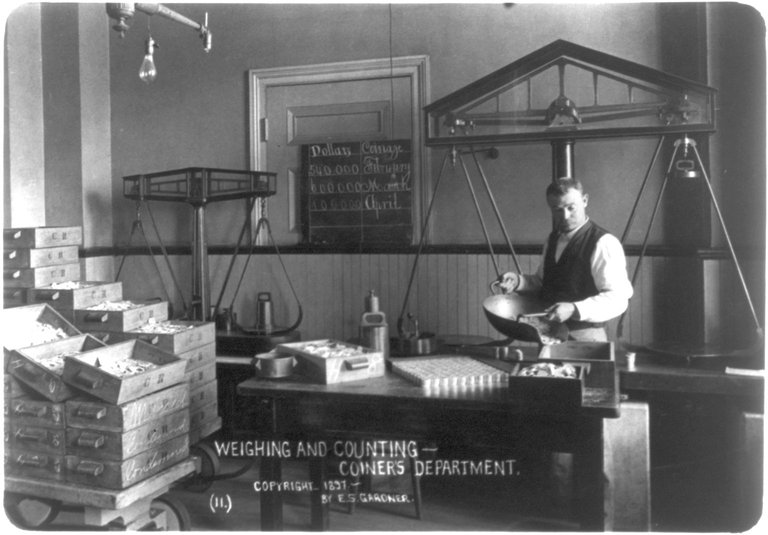

US Coiner's Department: weighting and counting of US dollars in 1897. Library of Congress[1]

US Coiner's Department: weighting and counting of US dollars in 1897. Library of Congress[1]

Some modern banknotes still display the promise of paying "bearer on demand", that's no longer the case anymore. However, for long time it was. The mere fact that the bearer could exchange their piece of paper for, say, a pound of gold, meant that the market value for that piece of paper ended up being precisely a pound of gold. Markets got acquainted with this idea and banknotes started to acquire an intrinsic value in the minds of the people.[2]

However, this came with complications. Government needed to have gold reserves to the amount that was promised across all the banknotes in circulation. A reduction in gold reserves had to be followed by an equivalent destruction of currencies. Likewise, increasing the money supply could only be achieved by acquiring larger gold reserves.[3]

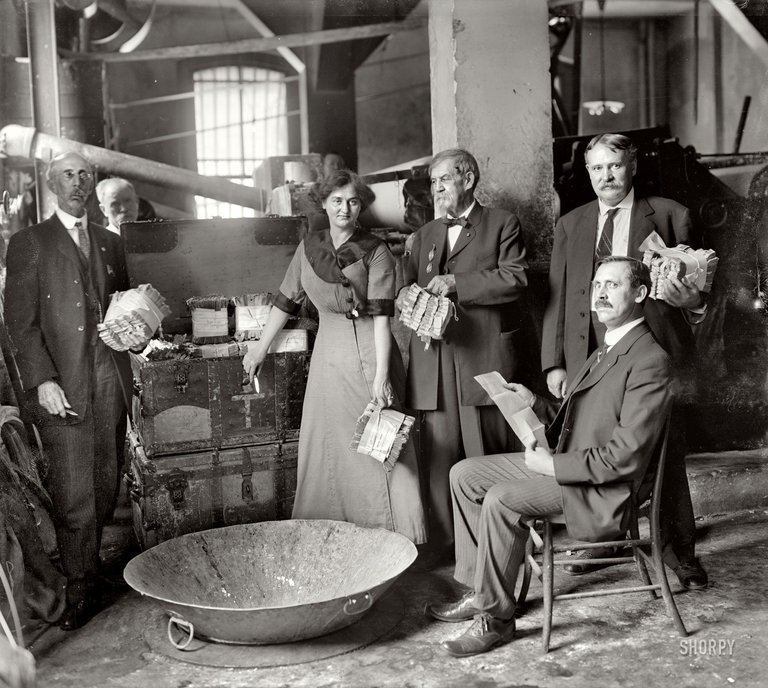

US Treasury Department, Bureau of Printing and Engraving. Destruction Committee. Maceration of old currency. Harris & Ewing Photo (1912)

US Treasury Department, Bureau of Printing and Engraving. Destruction Committee. Maceration of old currency. Harris & Ewing Photo (1912)

Although fractional reserves were in place[4] - generally speaking - for any material change in the gold reserves had to be associated an equally sized intervention in the money supply. This became a major issue during WW1, when massive amounts of gold reserves were transferred across countries, particularly from European countries towards the United States. As a consequence of such a drastic change in gold reserves, many countries halted the gold conversion and currencies started to be exchanged freely. Economists, however, firmly believed in the importance of fixed gold conversions for world trade and started to discuss a return to gold standard in the early 1920's.[5]

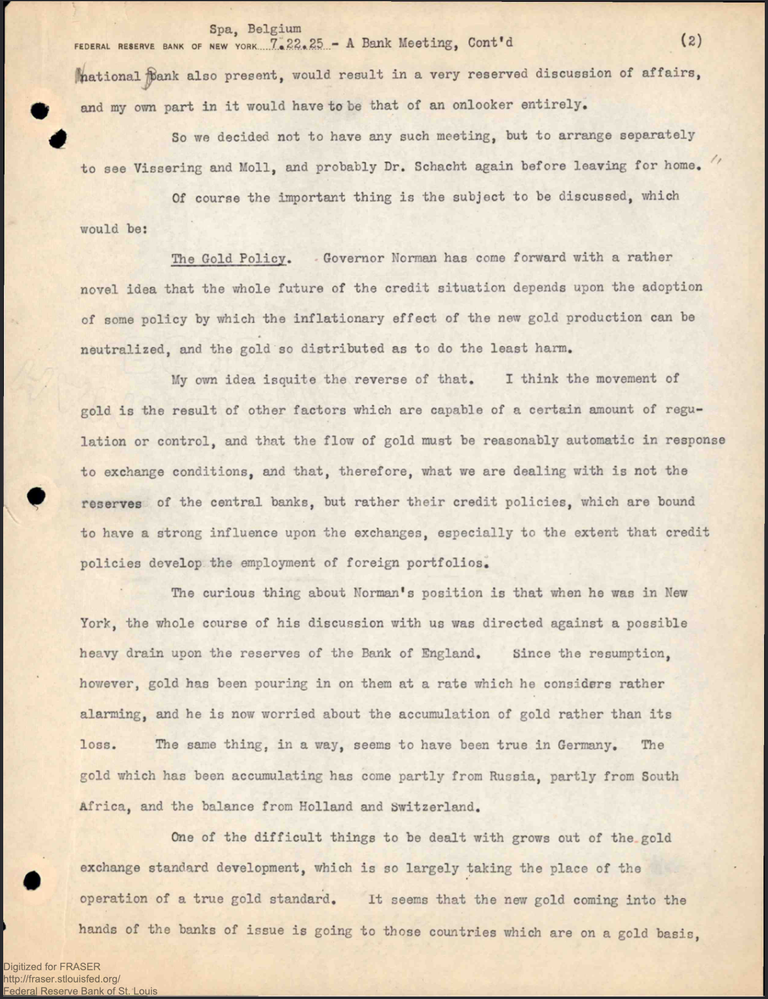

Declassified notes from FED president Benjamin Strong's trip to Spa (Belgium) in 1925, where central bankers met to discuss the return to the gold standard after some significant changes to national gold supplies in England, France and Germany. Particularly, Bank of England's governor, Montagu Norman was (rightly) concerned about how an abundance of gold reserves could lead to an appreciation of the British pound. Also governor Strong mentions how central bankers were discussing over the possibility a "gold exchange standard".[6]

Declassified notes from FED president Benjamin Strong's trip to Spa (Belgium) in 1925, where central bankers met to discuss the return to the gold standard after some significant changes to national gold supplies in England, France and Germany. Particularly, Bank of England's governor, Montagu Norman was (rightly) concerned about how an abundance of gold reserves could lead to an appreciation of the British pound. Also governor Strong mentions how central bankers were discussing over the possibility a "gold exchange standard".[6]

Eventually, the United States and many other European countries decided to revert back to the gold standard. Some countries reverted to what Fed governor Strong called "true" standard, where individuals could exchange their national currency directly for gold. Other countries (that is those whose gold reserves were most depleted) implemented a "gold exchange" standard, where individuals could exchange their national currencies to a determined amount of silver or foreign currencies (mainly USD or GBP) which in turn were pegged to gold.[7]

Regardless of whether it was a "true" standard or not, modern economists tend to consider the return to gold standard in the post-math of the war as a mistake. Over time it became evident how such the gold-standard system propagates every economic shock in any country to all the others.[3]

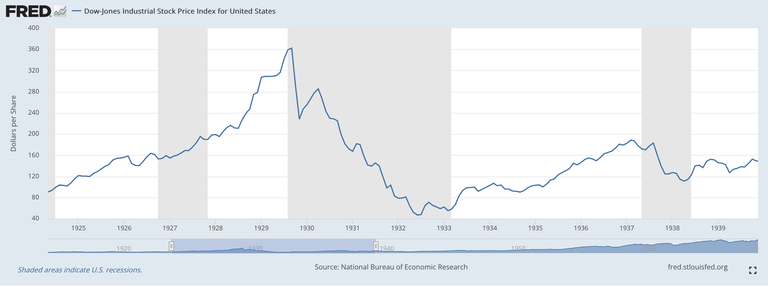

Modern economists claim that this is precisely what happened during the Great Depression of 1929, which lasted for nearly a decade. In 1929, the US stock market crashed, leading to a decline in GDP and a rise in unemployment that propagated from the US to all countries in the gold standard club.[8]

Average share prices in USD for Dow-Jones (1925-1940). Data from St. Louis Federal Reserve[9]

Average share prices in USD for Dow-Jones (1925-1940). Data from St. Louis Federal Reserve[9]

To enforce the gold standard, governments were forced to enact protectionist policies (tariffs, quotas and exchange controls) to avoid a dispersal of gold reserves.

However, those countries that were not part of the gold standard club, saw the convenience of having control over both fiscal and monetary policies. With free-floating currencies, government could sustain loose fiscal policies and most-of-all central banks could increase the money supply and reduce interest rates. Because of this, countries that were not adhering to the gold standard were significantly less affected by the Global Depression.[8]

Over time, "true" gold standard decreased in popularity across the globe. Central banks preferred the "gold exchange" framework, because they would have to exchange foreign currency rather than gold, thus avoiding a reduction in gold reserves. By the end of WW2, consensus was reached in Bretton Woods for a worldwide switch to the gold exchange standard. The only currency that could be exchanged for gold was the US dollar, while every other currency would be exchanged for the US dollar at a fixed exchange rate.[7]

Let's be clear. The gold exchange standard (and the "true" standard before) was very effective in avoiding fluctuations in the value of currencies while most countries that abandoned the standard during and after WW1 experienced much higher level of inflation. The gold exchange standard agreed in Bretton Woods also had very positive effects. Inflation during the 50s and 60s was very stable and very low. Discussions about the inefficiencies of the system were not so popular anymore.

The US Federal reserve, however, was forced to intervene several times to protect the value of the dollar. By the 1960s, European and Japanese markets were already large and competitive, causing a decrease in exports for the United States. This, combined with a not-marginal military spending, brought the US to worry about a future depreciation of the dollar and, thus, a potential run to the dollar.[10]

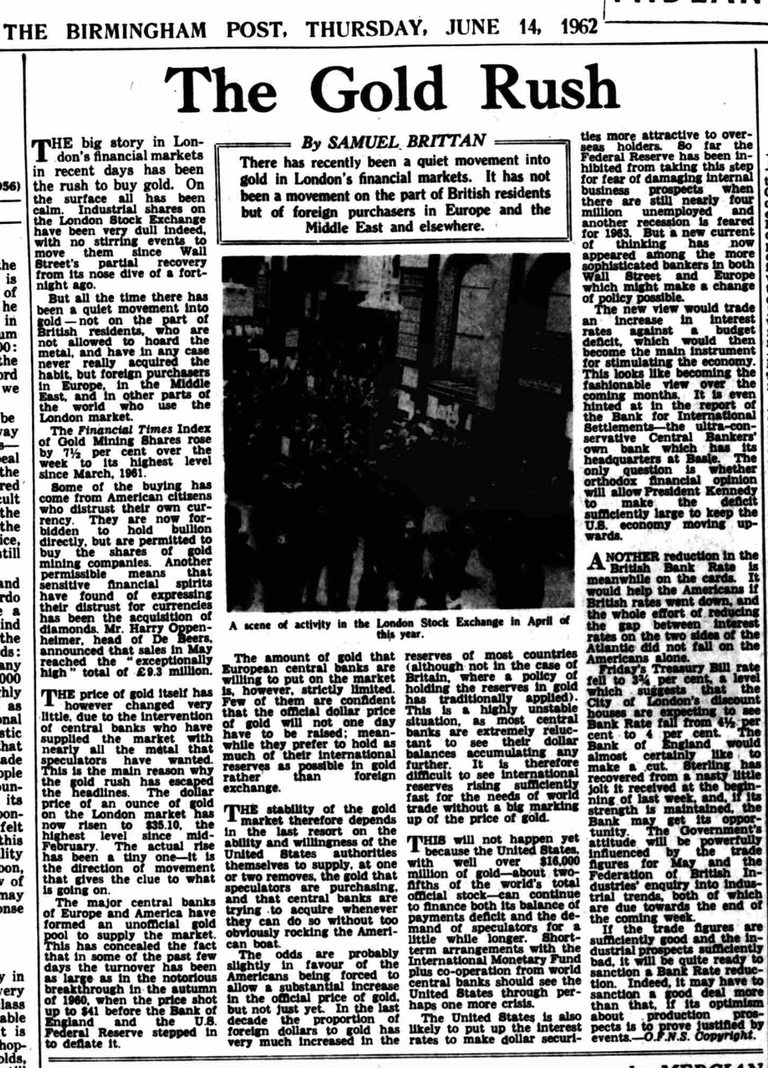

Gold runs were not limited to the United States. In 1961, the major European central banks formed together with the FED the so-called "London Gold Pool" to face the increasing demand on gold. No citation needed this time, because it's mentioned in the article below!

Fascinating article from the Birmingham Post in 1962. American citisens distrusting the US dollar went on a rush for gold. Quoting from the article (third paragraph): "The price of gold itself has however changed very little, due to the intervention of central banks who have supplied nearly all the metal that speculators have wanted". From the British Newspaper Archive[11]

Fascinating article from the Birmingham Post in 1962. American citisens distrusting the US dollar went on a rush for gold. Quoting from the article (third paragraph): "The price of gold itself has however changed very little, due to the intervention of central banks who have supplied nearly all the metal that speculators have wanted". From the British Newspaper Archive[11]

The constant trade-deficit of the United States created a dilemma, brought many economists to doubt the safety of the dollar as a global currency. This dilemma was later associated to the thoughts of a Belgian economist, Robert Triffin.

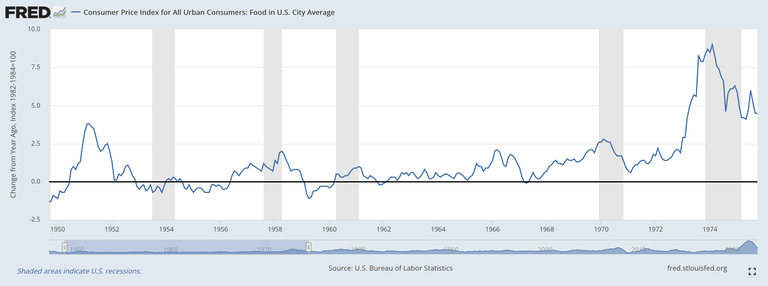

Finally, in the 1970s, the inefficiency of the gold exchange standard became strikingly evident. Despite the gold standard, high inflation arrived both in the US and in other developed economies. How was that even possible?

US food prices as annual percentage changes form 1950 to 1975. Data from St. Louis Federal Reserve

US food prices as annual percentage changes form 1950 to 1975. Data from St. Louis Federal Reserve

The point is that a gold standard is very effective in avoiding inflation from currency devaluations: when a currency weakens, prices increase because foreign goods become more expensive. As currencies are prevented from devaluing, the gold standard prevented this kind of inflation.

However, the gold standard nothing could do to avoid inflation deriving from higher spending. And that's precisely what happened in the 70's. An increased military efforts in Vietnam, a "war on poverty" and higher Medicare spending widened the US deficit and generated higher levels of inflation.[12]

Not only the gold standard did not prevent inflation to occur, but it made it worse. For one, it did not allow central banks to do anything about it. On top of that, as already mentioned above, it didn't allow currencies to devalue. When currencies devalue, exports increase (because internally produced products become cheaper for foreigners) and an increase in exports boosts the economy.

In August 1971, Nixon met with his economic advisors and FED chairman Arthur Burns to discuss how to deal with high inflation and high unemployment. On August 15, president Nixon appeared on television announcing a new economic plan, which included a "temporary" suspension of the convertibility of the US dollar into gold.[10]

Courtesy of the Richard Nixon Foundation.President Nixon ended the gold standard, for ever. Without a gold convertibility, the US dollar became a fiat currency whose value was to be determined on the Foreign Exchange market. Of course the dollar depreciated, precisely as Nixon himself anticipated.

In a post-gold standard world, central banks were now responsible for money stability through their monetary-policy decisions. Macroeconomists started to discuss the role and priorities of central banks and how these could be achieved through different policies.

As of writing, central banking is still a relatively new discipline and economists to this date are debating the most optimal target for central banks and the effect of different monetary policies.

In the 1970s, the most popular theory was that of "Monetarism". Monetarism gives a central role to the money supply, i.e. the total amount of money in circulation and argues that GDP and inflation are primarily dependent on the money supply.[13]

Monetarism follows the Quatity Theory of Money, which assumes inflation to be the result on the money supply and the velocity of money. The velocity of money represents how often and how quickly money circulates in the economy. Monetarists in the late 70s argued that the velocity of money could be assumed to be constant over time and that inflation could be kept under control by changing the money supply.[13]

The first years of US central banking didn't produce brilliant results. In 1973 the oil crisis took place, which brought inflation above 10% both in the US and around the world. However, this inflation was driven by an external shock. And central banks little could do to tame inflation generated by an increase in oil prices which entered production costs. As the oil crisis started to fade, though, inflation rates remained around 6%.

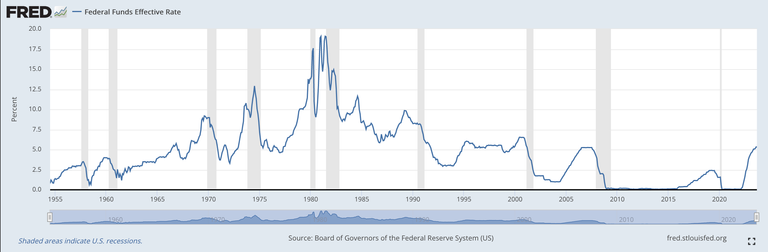

This is the situation that Paul Volcker inherited when he was nominated Fed Governor. Volcker believed in Monetarism and thought reducing the money supply was key to reduce inflation. His policies in late 70s and early 80s were later defined as the "Volcker's shock": interest rates were raised close to 20% by significantly reducing the money supply.[12]

Federal Funds Effective Rate, showing the effective rate target by the FED. Data from St. Louis Federal Reserve

Federal Funds Effective Rate, showing the effective rate target by the FED. Data from St. Louis Federal Reserve

The "Volcker shock" worked. Inflation subsided relatively quickly and Monetarist ideas gained popularity. Unfortunately, however, Monetarism didn't prove to be so effective in managing inflation as much as it was in reducing it. While no economists would debate that the massive reduction in money supply from Volcker was key to the reduction in inflation, the direct link between any change in money supply and inflation (particularly when inflation is low) is much less evident.

Managing interest rates, rather than the money supply, was argued is a much better policy. To this day, most central banks operate under this framework. I will develop this in a different article.

In general, you can expect my future articles to continue on these very topics. How effective have been the monetary policies in the past two decades? What alternative policy frameworks could be envisaged? And so on.

References:

Friedman, Milton, and Anna J. Schwartz. "Has government any role in money?." journal of Monetary Economics 17.1 (1986): 37-62. ↩

Meltzer, Allan, and Saranna Robinson. "Stability under the gold standard in practice." Money, History, and International Finance: Essays in Honor of Anna J. Schwartz. University of Chicago Press, 1989. 163-202. ↩ ↩

Selgin, George. "The rise and fall of the gold standard in the United States." Cato Institute policy analysis 729 (2013). ↩

Eichengreen, Barry, and Peter Temin. "The gold standard and the great depression." Contemporary European History 9.2 (2000): 183-207. ↩

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/archival-collection/papers-benjamin-strong-jr-1160/foreign-countries-2140 ↩

Laughlin, J. Laurence. “The Gold-Exchange Standard.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 41, no. 4, 1927, pp. 644–63. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1884885. Accessed 18 Oct. 2023. ↩ ↩

Eichengreen, Barry, and Douglas A. Irwin. "The slide to protectionism in the great depression: who succumbed and why?." The Journal of Economic History 70.4 (2010): 871-897. ↩ ↩

By Dylan Matthews, How the Fed ended the last great American inflation ↩ ↩

Jahan, Sarwat, and Chris Papageorgiou. "What is monetarism." Finance and Development 51.1 (2014): 38-39. ↩ ↩