Inflation is probably the macroeconomic term that most non-economists have at least a passing understanding of and relationship with. From the baby boomers of the industrialized world, who experienced the detrimental effects of high inflation on their own wallets throughout the 70’s and 80’s to the following generations, who from time to time saw (hyper)inflation rear its ugly head around the world throughout the world in the media during the 90’s and 00’s and witnessed the, at that time, hitherto unprecedented deficit spending by especially the American government during the real estate crisis beginning in 2007.

Despite this, the common understanding of what inflation entails and the reach of its detrimental effects is – as is with most economic phenomena – very limited at best and also something that most normal people in the westernized world have had very little real exposure to throughout the last thirty or so years. That, however, is about to change and hence I thought the time was right to take a closer look at this beast

.jpg)

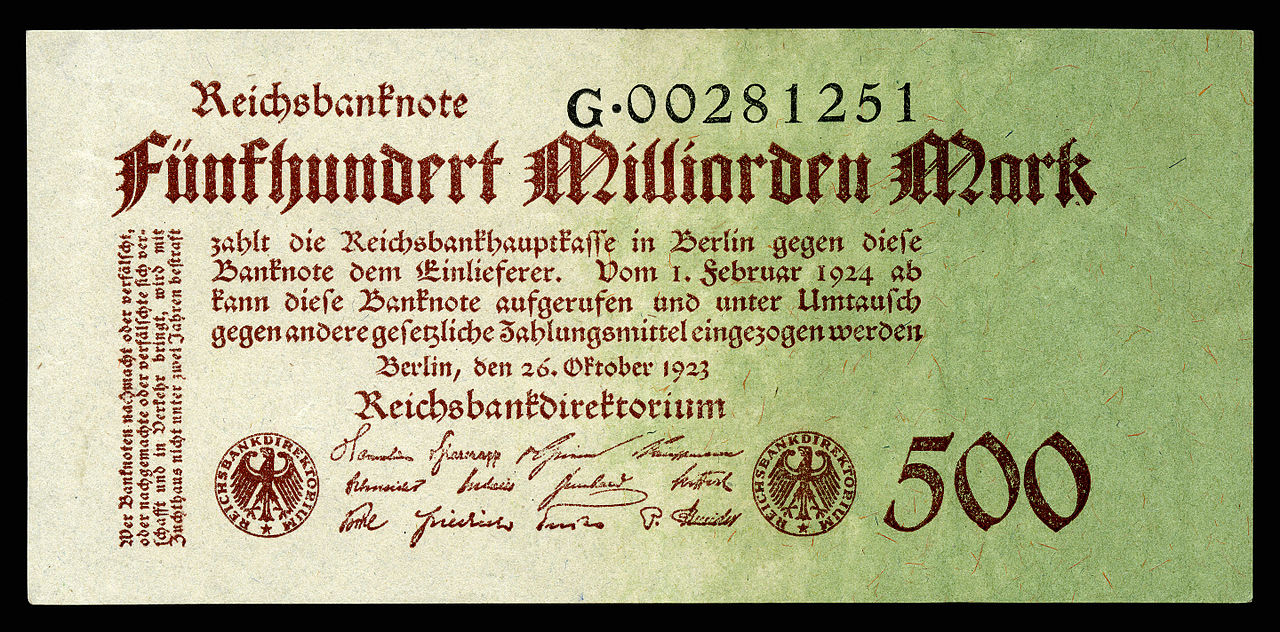

a 500 billion mark note from the Weimar republic, one of the most widely recognized examples of hyperinflation - picture from wikipedia

The purpose of this blog post is not only to shred some light on what inflation and its consequences are according to mainstream economics, but also offer an alternative, and in my opinion more comprehensive, take on the phenomena as presented by the Austrian economist Steve Horwitz as presented in his 2003 paper The Costs Of Inflation Revisited. This is done in part to hopefully provide an alternative to some of the more disastrous takes I have seen on inflation in mainstream outlets, but also to honor the memory of professor Horwitz, who unfortunately passed away in 2021.

Neoclassical economy: Inflation, the growth of prices

In neoclassical monetary economics, inflation is defined simply as the growth of prices: If you introduce more money into the economy, prices will rise proportionately. From this starting point, mainstream literature centers on four costs arising from inflation

A tax on money holdings

Rising prices mean that a given amount of money can buy less than before. This can be rephrased as inflation reduces the value of money. As a result, economic actors will hold less money by seeking out money alternatives (such as investing the money instead, for example) that are not exposed to inflation. This economic behaviour has its own costs associated with it: Banking transaction costs, which traditionally known as ‘shoe-leather costs’ as you actually had to take more walks to the bank to take money out, thus wearing out your shoes more quickly. In the current year, however, these transactions are more likely to be ATM fees or credit/debit card surcharges.

Inflation makes debt cheaper

Because debt amounts are nominal and not adjusted for inflation, debt payments (who are now worth less due to inflation) constitute a transfer of wealth from the creditor to the debtor. While this can be construed as a simply a transfer of wealth within the economy rather than a loss of wealth (which the word ‘cost’ implies), there is a possibility that ongoing inflation will make it less attractive to lenders to extend credit, resulting in an overall reduction of credit availability.

Menu costs

Adjustments to prices to goods and services due to the effects of inflation cannot be made costlessly: Changes in prices needs to be communicated to customers, computer systems need to be updated and new price labels, menus and pamphlets have to be printed, etc. This cost is known as menu costs in the economic literature, referring to the latter.

Changes in Relative Prices

Inflation can not only affect the general price level, but also adversely effect the price of goods relative to each other, so-called relative prices. For example, as adjusting prices to cope with inflation (the aforementioned menu costs) is not free neither in money nor time, there will be some actors who at any given time have managed to adjust his prices, while there will be other actors, who have not, resulting in a change in relative prices induced by the inflationary economic environment. It will also be difficult for actors in the market to discern whether a change in relative prices is due to a change in inflation, which may be temporary, and therefore require a limited adjustment to his economic planning, or whether it is due to a real change in the market, which will require much bigger action on behalf of the actor. This is a phenomenon known as the signal extraction problem.

The Cost of Inflation a la Horwitz

Horwitz’ paper offers a more expanded view of the costs of inflation, that draws from the insights of New Institutionalism, The School of Public Choice as well as Horwitz’ own domain, Austrian Economics. Below is a summary of what I find to be the most important points of the paper:

Relative price effects revisited

Horwitz’ theoretical framework questions the assumption that that increases in the money supply affects all holders of money equally. This is obvious in the case of increases to the money supply through stimulus packages aimed at different sectors or companies, but even if the money supply is raised through a central bank offering cheap credit to commercial banks, the banks will still receive the money first and some banks will receive the money before other banks. The relative price effects that the lending decisions of these first banks will generate will be different from the effects created by later banks, because the credit extended by the first banks has now changed the economic behaviour of their debtors. Moving on down the chain, the change in economic behaviour due to the extra capital available to these debtors incurs other relative price effects, and so on.

|

|

|

|

|

|

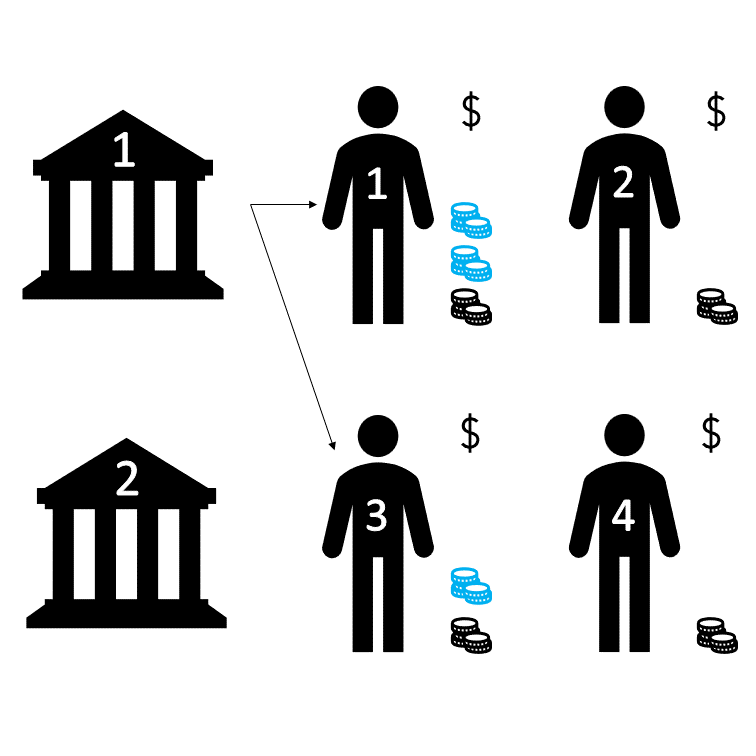

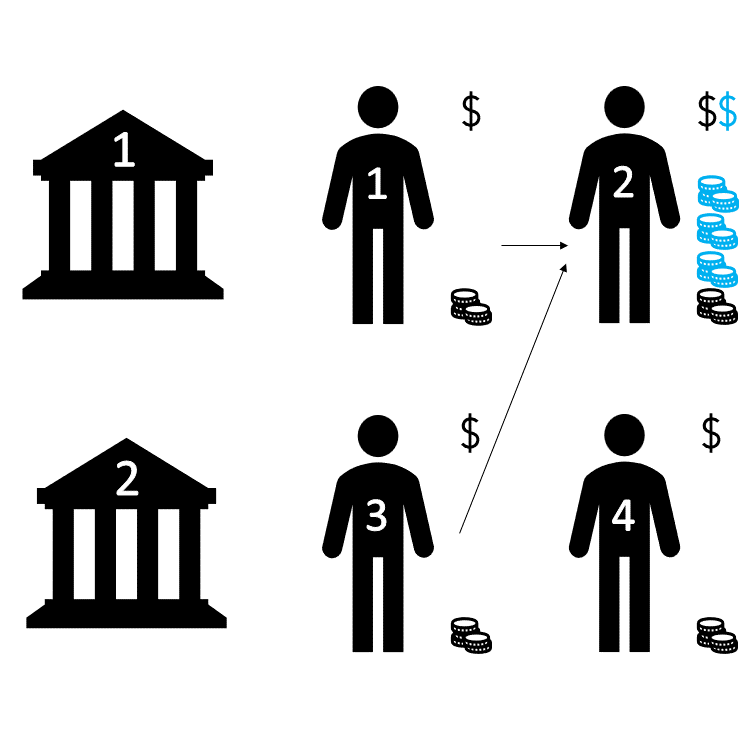

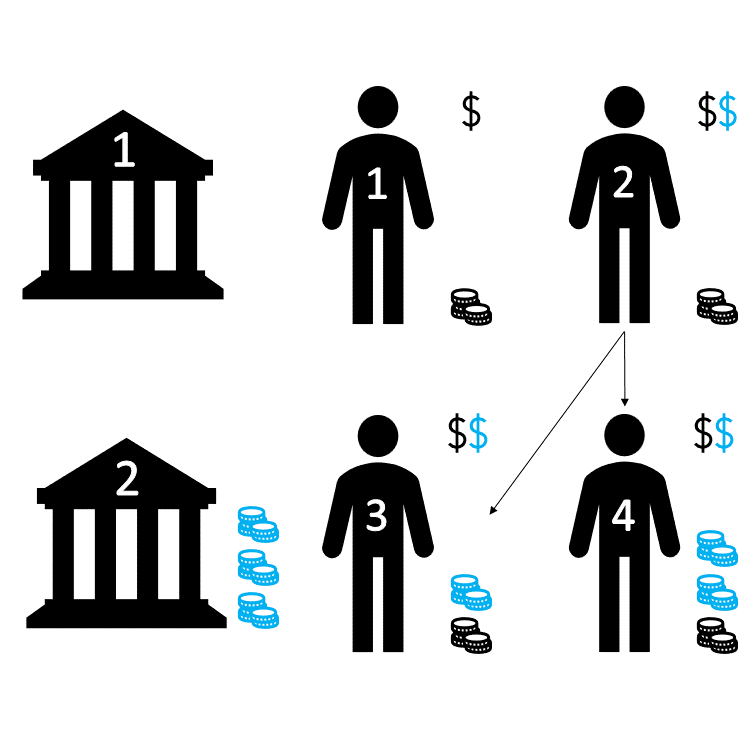

The above illustration seeks to illustrate the relative price effects that arises from money entering the economy unequally for the different actors. In the example, we have two banks, and four entrepreneurs each producing different products.

In picture 1, bank 1 receives an increase in their money supply from the central bank symbolized by the blue coins. In picture 2, bank 1 then lends out the money to entrepreneur 1 and 3, who then in picture 3 exchanges their blue coins for entrepreneur 2's products. Entrepreneur 2, experiencing a sudden demand for his products raises his prices symbolized by the blue dollar sign. When bank 2 in picture 4 receives their money from the central bank, entrepreneur 2 has exchanged the money for products from entrepreneur 3 and 4, who due to increased demand has raised their prices accordingly. The market that bank 2 is now lending money into has very different relative prices than the market that bank 1 lent money into in picture 1.

The Political Motives Of Inflation

If relative price effects can arise out of the unequal distribution of the new money created through inflation, it is easy to see that, if the direction of the new funds can be somehow controlled by political actors, they can confer benefits to certain interest groups over others. This is especially visible when it comes to inflation in the form of stimulus packages aimed at certain parts of the economy or the direct bailing out of certain firms and institutions deemed 'too big to fail' as seen during the financial crisis of 2008. Political actors can also benefit from the fact that in the case of inflation, the public will usually direct their dissatisfaction with rising prices onto 'greedy corporations' rather than the government, who initiated the rise in the money supply. This gives government the power, using government programs and stimulus packages, to selectively intervene in the economy, where it is the most politically expedient and as temporary government programs tend to stick around long-term ("there is nothing as permanent as a temporary government program" as Milton Friedman said) further distorting the markets that they were supposedly put in place to rectify.

Prices as a predictive tool

One of the more unique features of Austrian economics is the emphasis put on prices. For Austrian economists, prices set in a free market are what allows for economic calculation. This includes both gauging whether or not a given business venture stands a chance of being profitable (i.e. the sales price of whatever you are bringing to the marketplace exceeding your inputs in terms of labour and capital) and market discovery, i.e. finding new and novel ways of combining labour and capital into products or services. Inflation reduces the epistemic properties of prices, making economic calculation harder, both in determining the success of a business venture (am I selling at the current price due to market demand or due to a price level artificially heightened by inflation?) and in terms of market discovery (is the price of my inputs a reflection of the market or is is distorted by relative price effects induced by inflation?). This incurs an additional knowledge burden on market actors that now not only will have to navigate the market normally, but also predict the effects of inflation and the intention of policy makers as well as try to discern whether price changes are due to inflation or underlying market conditions, as described above. This has the potential to lead to marked error (i.e. failed businesses) or at the very least, additional costs of doing business.

Coping costs

Besides menu costs, which refers to the cost of updating prices, inflation can force actors into changing economic behaviour or spending money on services that they would not otherwise need to hedge against inflation. This is what Horwitz refer to as coping costs. An example of the former can be consumers moving their cash savings into stocks thereby avoiding the effects of inflation on their savings, but also taking on more risk that they would otherwise have liked, and firms spending additional funds on financial advisory to better counteract the effects of inflation is an example of the latter. In times of severe, prolonged inflation, such expenditure on what you with a gamer term could call 'support' functions could even take away from productive activities, i.e. being competitive in the market. This makes coping costs all the more insidious as the increased business activity in the support sectors registers as economic growth in GDP terms, but this hides the fact that these were expenditures that most likely would have gone into creating better goods or services had it not been for inflation.

Summing up

In this blog post, I have attempted to juxtapose the mainstream view of the detrimental effects of inflation to Horwitz' expanded view. While I have not touched on every single point made in the paper, I have nonetheless tried to the best of my ability to rewrite his most important points into layman's words. Whether or not I have been successful in doing so, you can let me know in the comments.

Thank you for reading! If you like this blog post, I can really recommend reading the original paper as it expands on a lot the points I have summarized above. Please leave an upvote and a comment about your thoughts in the movie and please consider following me as well!