Let’s talk about humanity...

Human civilization was not ready for COVID-19, nor is it ready for the continuing impacts of climate change, nor the impacts we will increasingly feel as we automate more and more employment. As a species, we were not ready. We’re still not ready. And we will continue not being ready, until we make some fundamental changes to the human social contract, because from the very beginning, we’ve never been ready. The change I personally believe is of primary importance above all other needed changes, and the one I’m about to make the case for, is the concept of unconditional basic income, also known as universal basic income, basic income, or just UBI.

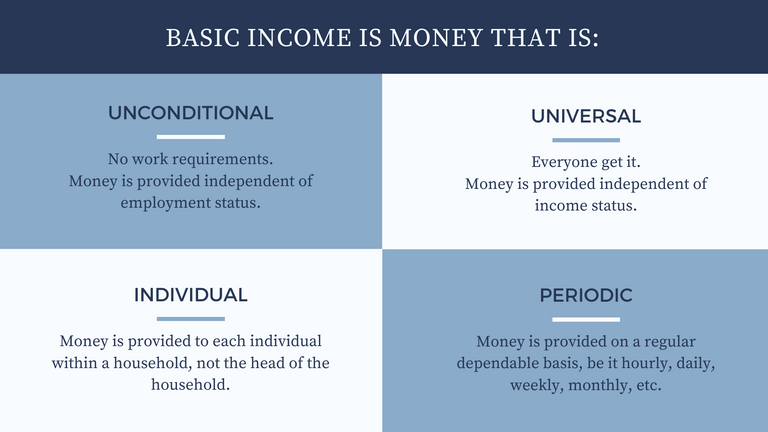

First, what is basic income? Basic income is society investing in itself with a form of social security that’s unconditional, universal, periodic, cash for each and every individual member of society. What makes UBI so different than other forms of social security is that it’s built on a foundation of trust. In fact it is a foundation of trust. UBI doesn’t care if you’re employed or not. UBI doesn’t care if you’re poor or not. UBI only cares that you are human, and you are alive. Because you are alive, you need sufficient access to resources to stay alive, no questions asked. Humans are the only species on Earth who have to pay to live here. UBI is the recognition that if we’re going to make everyone pay to live, we should provide everyone the money to live.

Why would we do that? That’s crazy you may say. People would stop working, you may say. We couldn’t possibly afford it, you may say. Well, two decades ago, I may have agreed with you for saying those things, but not anymore. Now I know that it’s the lack of basic income that’s crazy. And the better questions to ask are, “How much work isn’t getting done because people lack basic income?” and “How much does it cost for society not to invest in itself with basic income?” Doing nothing is never free. Not being able to afford to be productive is not good for productivity. We have these things all backwards.

It’s like human civilization is a city built on sand. In such a world, it’s normal for buildings to be full of cracks. It’s normal for buildings to fall and for people to sink, but just because it’s normal doesn’t make it right. It doesn’t make it sane or rational. What’s normal right now should not be normal. Poverty should not be normal. Chronic insecurity and extreme inequality should not be normal. Diseases and violence born from lack of food and shelter and the unceasing fear of not having enough to survive should not be normal. We built human civilization to be like this. We constructed this. We can build a new normal upon a solid foundation. That foundation is UBI.

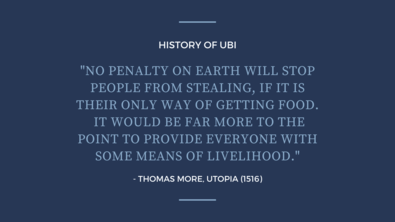

The basic concept of basic income can be traced back as far as Thomas More in the 16th century, when he wrote, “No penalty on earth will stop people from stealing, if it is their only way of getting food. It would be far more to the point to provide everyone with some means of livelihood.” The point of course is to get us all to think about how much sense it makes to throw people in prison for the crime of essentially not having enough money. What if we instead just provided people enough money?

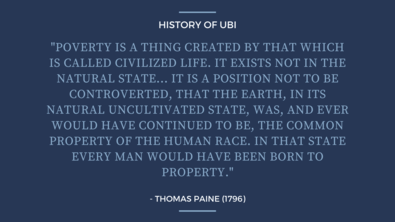

It was Thomas Paine though who made perhaps the strongest case for basic income over two hundred years ago, with his essay “Agrarian Justice.” In it he makes the point that the creation of what we call civilization made most people better off, but it also made some people worse off, and that’s the core problem that needs to be resolved. The original sin of civilization is the disinheritance of what would have been everyone’s natural inheritance in the form of common property. Because everyone would have otherwise been born with free access to land and natural resources, compensation is due, and so he envisioned a universal provision of money for everyone upon reaching the age of 21, in order to begin their lives with inherited capital, not as any kind of charity or welfare, but as a human right.

Centuries later, in 1982, the state of Alaska in the United States became the first government to bring Thomas Paine’s vision to life in the form of the Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend, where every resident of Alaska, poor or rich, young or old, employed or unemployed, receives a check every year as their rightful share of Alaska’s natural resource wealth. The check has averaged between $1000 and $2000 every year, and no Alaskan sees it as unearned income, but as a rightful earned dividend based on a shared belief in common ownership of natural resources.

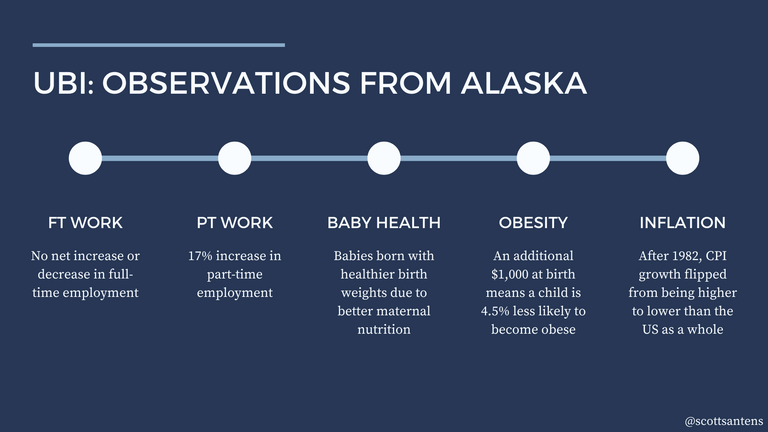

Yes, Alaska has had a yearly UBI for almost half a century. It’s the only place in the world to have implemented a permanent UBI so far. What has happened as a result you may ask? Well, the answer is quite a few notable things. First and foremost, it has reduced poverty by lifting tens of thousands of Alaskans out of poverty every year. A 2016 study by the University of Alaska estimated that if the UBI were eliminated, child poverty in Alaska would be increased by one third. The UBI has also increased employment. Research done in 2018 at the University of Chicago concluded that Alaska’s UBI had increased part-time employment by 17% and had a net neutral impact on full-time employment, with some people choosing less employment while others who would otherwise have remained unemployed were able to get jobs thanks to the new jobs created by people spending the money.

Other observations from Alaska include babies born with healthier birth weights due to better maternal nutrition, reduced rates of obesity and crime that both scale according to the size of the payments, more savings, less debt, and a slower rate of inflation growth as measured by the consumer price index compared to the rest of the US that began when the dividend payments started going out.

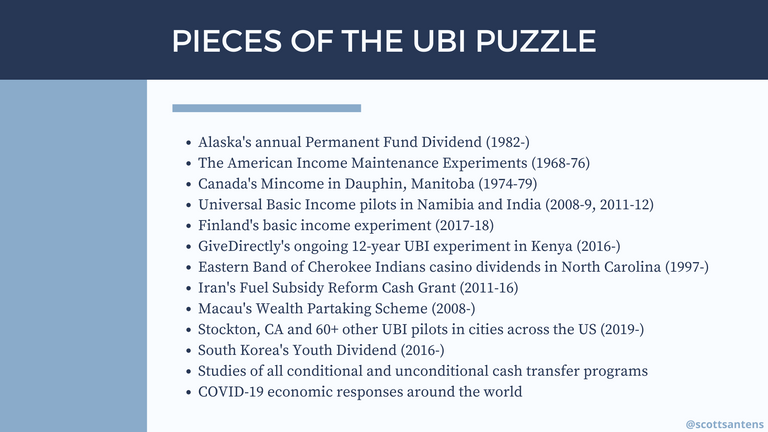

Although Alaska’s annual dividend is effectively the longest running UBI program on Earth, there are other programs around the world that we can learn more about UBI from, through their provision of unconditional cash. There have also been full UBI experiments carried out in countries like Namibia, India, Uganda, and now Kenya where entire villages have received unconditional cash universally. Finland has done a basic income pilot for the unemployed and Stockton was the first city in the US to run a pilot, which has now been followed by over 60 more cities and still counting, including my own city of New Orleans. I consider all of these and more, pieces of the UBI puzzle that together create a clear picture of its effects.

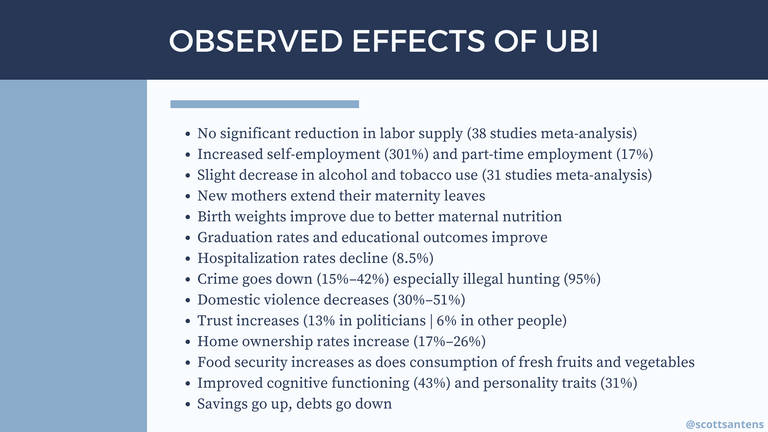

The following is just a sample of the observations made so far across programs and pilot experiments centered around cash provided unconditionally: First and foremost, there is no significant reduction in labor supply. To the contrary, labor supply has been found to increase globally among adults, men and women, young and old, with decreases usually only observed in children, the elderly, the sick, those with disabilities, women with young children to look after, or young people who opt instead to pursue education. Additionally, large increases in entrepreneurship are frequently observed for three primary reasons: UBI functions as startup capital, consumer buying power, and it reduces fear of failure.

Next, people spend their UBI just like all of us would. It tends to be spent on food and housing. What it’s rarely spent on is drugs and alcohol. In fact, overall, UBI tends to reduce drug and alcohol use. This of course makes sense. Drug abuse tends to be self-medication in response to chronic stress. Because UBI reduces stress by supporting a sense of real security, mental health improves. In fact, health improves overall quite dramatically. In the Manitoba pilot, hospitalization rates fell by 8.5%. Imagine a vaccine that increased everyone’s health so significantly that one out of every ten people no longer got sick enough to seek hospital care. Babies tend to also be born healthier, as a result of better maternal nutrition, which has lifelong health impacts. Childhood obesity also decreases. The health impacts of UBI are profound due to three primary pathways: more basic needs met, less inequality, and less insecurity.

Crime reduction is also another repeated observation of basic income. In the Namibia pilot, overall crime went down by 42%, and in Canada’s Manitoba pilot it went down by 15%. The degree to which crime is reduced also varies by the crime, which says a lot about the desperation that lies underneath certain crimes in particular. In the Namibia pilot, illegal hunting plummeted by 95%. Consider for a moment just how much money could be saved by dramatically reducing crime.

Basic income also impacts how we treat each other. In Kenya, there were half as many incidences of women being kicked, dragged, or beaten. In Canada, domestic violence dropped by 30%. In Finland's experiment, recipients of basic income began to trust politicians, the legal system, and their fellow citizens more. Social cohesion increases. Children raised in households with basic income show increases in agreeableness and conscientiousness, meaning they’re more responsible and respectful. They also tend to do better in school and earn more as adults.

These are just some of the observed effects of basic income security. There’s more we already know, and there’s more we’re still learning, but just think for a bit about the available evidence and apply it all to the question of how much UBI costs. How much does not having UBI cost?

A society without UBI spends a huge amount of resources on treating the lack of UBI. In the US, the cost of child poverty alone has been estimated as costing us over $1 trillion a year or 5% of our GDP. It’s also been estimated that every dollar spent reducing child poverty results in eight dollars of economic benefit. And that’s just child poverty. What are the full costs of poverty across the entire population? What are the full costs of crime? What are the full costs of people not reaching their full potentials? What are the full costs of physically and mentally unhealthy people that would otherwise be perfectly healthy if they just had enough money and stability?

When we look at the big picture, it’s a lack of UBI that’s hugely expensive. UBI is an investment with a high ROI. There’s no better investment to be made than investing in every single member of society with enough money for them to be a truly integrated participant in society.

It’s also important to understand what’s already being spent to alleviate these problems in less efficient ways than basic income, and with less trust and dignity, but much more bureaucracy. Consider all the government assistance programs that could be accomplished with cash, and how many tax deductions and subsidies could just be cash instead of tax cuts. Governments do so much because of a lack of UBI, and do so much that could be UBI instead.

Basic income is really just a matter of doing a lot of things already being done, but unconditionally, universally, and with cash instead, and as a result, no longer needing to do so many other more costly, less effective things.

Now that we’ve covered the basics of UBI and its many positive effects, and understand it for what it really is - an investment in a social vaccine that inoculates against poverty, extreme inequality, and chronic insecurity - let’s talk about the pandemic and the lessons human civilization as a whole should take away from this experience to apply to future disasters.

Here’s the deal: There will always be another disaster. It’s Murphy’s Law. Whatever can go wrong, will go wrong. Knowing that, failure therefore has to be a part of design. We don't want things to fail, but we know they will, because they always do, so what should be done?

The answer reminds me of an engineering joke about what 1 + 1 equals. 3 just to be sure.

The answer is fault tolerance and this is what I call the engineering argument for UBI. In the event of component failure, a system should be designed to continue functioning either as normal, or at a reduced capacity. And when some system does fail entirely, it should be designed to return to 100% operating capacity quickly. Catastrophic failure should always be avoided, especially for mission critical systems, and even more especially when lives are at stake.

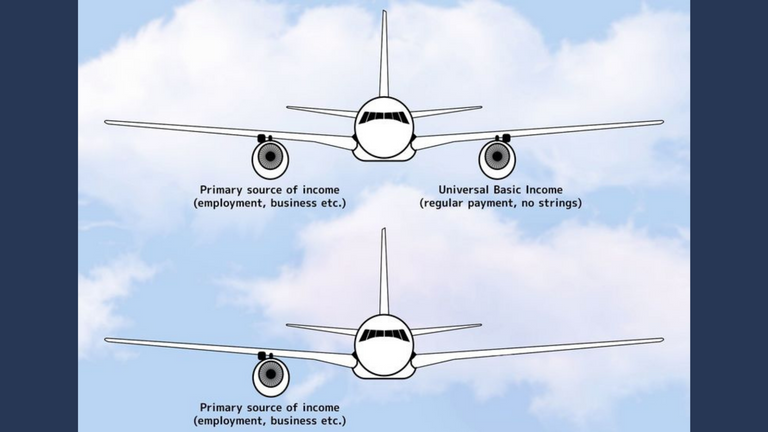

Consider planes. If a single component fails, it shouldn't bring the entire plane down. There are ways of avoiding that by incorporating redundancy so that multiple backup systems have to fail in order for the entire plane to fail.

Because we know things will very likely fail, we should design them in a way such that when they fail, lives are protected first and foremost, wherever lives are at risk. In elevators, it would be bad design for them to plummet with the loss of power. Instead, they utilize fail safe design, where power keeps the brakes off and loss of power activates them. They fail into a safe state, ergo "fail safe."

So what does this have to do with basic income? We know that our primary income distribution system fails. It fails all the time. It's called losing your job. We have a safety net designed to catch people when it fails, but that system also fails all the time too, at which point, people can and do die as a result. We have engineered a life support system without fault tolerance, and we did it because engineers didn't design the system.

Realism demands that we recognize human beings need money to live. It is mission critical for people to have money to spend on what they need to live. So just make sure they have it, by supplying it to everyone unconditionally. Here's how UBI would introduce fault tolerance into our life support system we call the economy:

First, everyone starts with the money they need to live. We wouldn't create a life support system on a space station where in order to receive oxygen, one would need to work to obtain it. Life support is life support. Dead people can't work. So make sure people get oxygen so they can stay alive. Living people will do much more work than dead people.

Next, everyone who works for additional money would be utilizing redundancy. They would have two streams of income. If they did multiple jobs or began earning passive income of some kind, it would be three streams of income or more. Instead of a one-engine plane, they could have two or three or more engines keeping them in the air. If one engine failed, they'd have others, and because of the UBI, they'd never have none.

Because UBI would mean incomes never fall to zero, anyone who ever loses their job would fall to the level of the UBI instead of the severe poverty of having $0. We can think of this as what engineers call "graceful failure." Graceful failure means that a failure does not result in catastrophic failure (e.g. sickness or death), and instead fails in a way that protects people or property from injury or damage.

With UBI, people who lose their jobs would fall to a state preferably above the poverty line, meaning that failure would never result in poverty. This builds resilience into the system. People who still have something instead of nothing are more able to get back up again, and find new employment. They are also more likely to take innovative risks, secure in the knowledge that failure won't result in death.

This is the engineering argument for UBI: We are all living, breathing, human beings, and we all need money to obtain the food and housing and everything else we need to stay alive. The best way to make sure we all stay alive then, is to make sure we always have a basic amount of money, and the best way to make sure we always have a basic amount of money is to provide it to everyone at all times, so it's always there, no matter what.

Any argument to the contrary is not sound from an engineering perspective. Failure is inevitable. There will always be mistakes made. There will always be job loss and bad luck. There will always be safety net failures. There will always be disasters. There will always be pandemics.

Therefore, we should always have basic income, so that when these things happen, we are less likely to die, and more likely to scrape ourselves off, and get right back up again. Unconditional basic income is how to engineer resilience into our social and economic systems.

Everything would be different if every country had already had UBI in place before Covid hit. There are so many ways UBI would have changed the way the pandemic went and how it impacted people, and what the US did and didn’t do illustrates this point surprisingly well.

When Covid hit the US, people got sick, and as is often the case, people didn’t stay home because they couldn’t afford to. They went to their jobs, because they felt no other choice in order to pay the bills, and they got others sick as a result.

What if everyone had instead felt the security of knowing that if they stayed home, they’d still be able to pay their bills? How many more people would have quarantined?

When the lockdowns were imposed and people were ordered to stay home, tens of millions of people lost their jobs and businesses began to shutter. Because workers are also customers, the incomes of many people who kept their jobs went down, which caused more businesses to shutter.

What if no one’s income had dropped to zero, and more people had been able to continue being customers? How many more businesses and jobs would have survived? How many incomes would not have fallen at all, or as much?

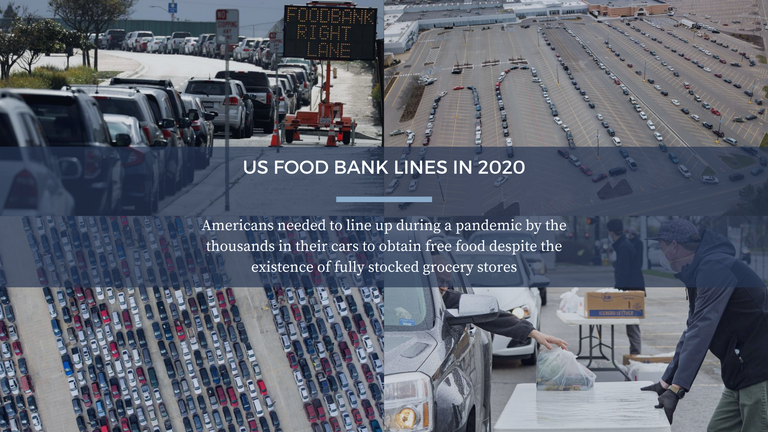

When unemployment skyrocketed and before the first stimulus checks had been issued, there were miles long lines of cars at food banks across America. Millions of Americans who’d never visited a food bank before suddenly needed them for the first time in their lives, while at the same time grocery stores were full of food for sale as normal. It’s not that there wasn’t enough food in stores for people to buy. In fact at the same time farmers were plowing crops under, after having lost their restaurant buyers. It’s that people didn’t have enough money to buy food.

What if everyone had never stopped having enough money to buy food? Would we even need food banks?

When mass unemployment meant millions of Americans could no longer pay their rent, our answer was to prevent evictions. Some people still got evicted in the middle of a pandemic despite the eviction bans, and small landlords that rely on their rentals for their own income, meant that many landlords also lost their own incomes as a result, and some even became homeless despite literally owning homes.

What if everyone had never stopped having enough money to pay their rent? How many fewer people would have been evicted from their homes, or would ever need to be evicted? How many fewer people would ever experience homelessness at all?

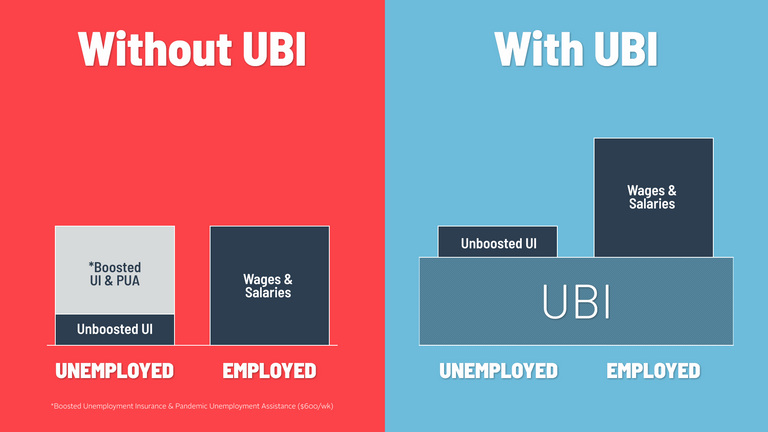

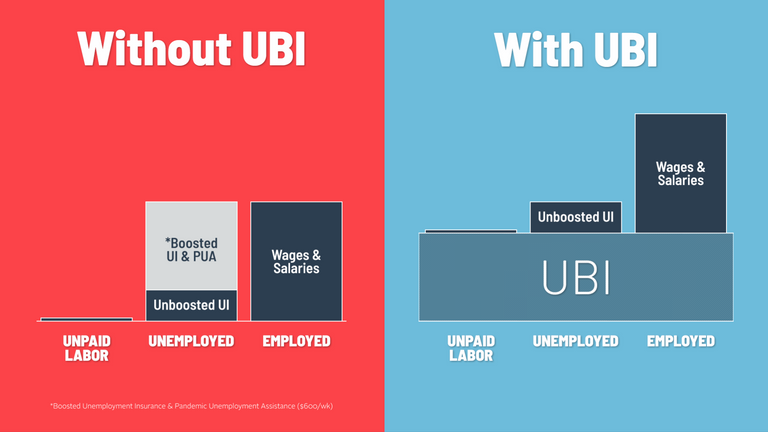

When the world became divided into essential workers and non-essential workers, essential workers turned out to be among the lowest paid, while non-essential workers were the ones with higher incomes and also more able to work from home. In the US, we decided to boost the incomes of the unemployed with a $600 a week boost across the board to all unemployment checks. On the one hand, this was a smart thing to do in order to make sure that tens of millions of unemployed Americans didn’t fall behind on their bills. And because so many people had been earning so little, the unemployment boost served to actually increase the incomes of two out of three unemployed people above what they’d been earning. On the other hand, the workers considered essential who were also earning low incomes, did not receive a boost, which resulted in a lot of bitterness and justified cries of unfairness that so many of the non-essential unemployed were lifted above the essential employed.

What if instead of boosting only the unemployed, there had been a floor of income already beneath both groups?

Additionally, when mass unemployment occurred, we immediately admitted that there was an entire group of unemployed people that would have otherwise gotten nothing, for having jobs that didn’t qualify them for standard unemployment insurance. So we created the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program to provide the same $600 a week to the self-employed freelancers and gig workers that have long been excluded from the safety net.

What if an income floor wasn’t tied to employment at all, so that it could help everyone regardless of the type of employment they have whenever they lose it, and for however long it takes to find new employment, be it full-time or gig economy work?

Then there is the issue of recognizing all work, not just paid work. As schools across the US closed, kids began to spend a lot more time at home, which meant parents needed to spend a lot more time at home too, even if they were employed, to the point that many parents needed to leave the workforce, and those who left to care for their kids were disproportionately women. Parents weren’t quitting to sit at home doing nothing. They were quitting so that they could work at home and not get paid for it, because the work that involves caring for our kids and our elders and even members of our community tends to go unrecognized as work because it’s unpaid. But of course it’s work, and those who quit to perform it got nothing for being newly unemployed, unlike the newly unemployed who qualified for $600 a week in unemployment insurance or pandemic unemployment assistance.

What if an income floor always existed underneath all forms of work, so that it enabled and supported all kinds of work, regardless of how valuable the rest of society considered it to be? What if unpaid caring and community volunteering were options that more people could afford to perform, because their basic needs were covered and working for free was finally possible for everyone to choose?

The unemployment check boost has since expired in the US, but not before it had some other lessons to teach us. A very large experiment was effectively launched when half of all states canceled the boost early, while the other half kept the boost in place for another few months. The belief was that the boost was resulting in jobs going unfilled, and that they essentially needed to be forced back into the labor market by reducing people’s incomes or even dropping them to zero. The result was no significant increase in employment after dropping people’s incomes. Instead it just caused more misery and less consumer spending. Apparently there were other reasons that jobs were going unfilled, like low pay, bad hours, poor conditions, closed schools, lack of childcare, and the fact a pandemic was still filling hospitals and killing people.

What if there were a permanent income floor under everyone, so that people’s incomes could never drop to zero during a pandemic, or any disaster, or ever for that matter?

It is in fact because of all the factors hindering employment that has resulted in the strongest labor market the US has seen in decades as employers compete for employees. Wages are going up. Work arrangements are getting more flexible and some are even switching to 4-day weeks. Unions are negotiating better contracts. For the first time in a very long time, the incomes of the bottom 40% are rising faster than inflation, even in an environment of temporarily higher inflation, because workers actually have real bargaining power.

What if workers always had real bargaining power? What if workers could always walk away from the negotiating table and choose to withhold their labor until their demands were met? Strike pay enables that for union members. What if everyone always had strike pay, regardless of union membership?

Americans got a taste of what that might be like, when most of us received three different stimulus checks, two in 2020, and one in early 2021. The majority of Americans got to personally feel what it was like to check their bank account, and see a payment just appear there, almost by magic. For some, these payments were life-changing. Because they went to people regardless of employment status, these checks reached people who didn’t get any unemployment income, but who had lost income despite maintaining employment. This was no small number of people either. One third of all Americans lost income but didn’t get any unemployment because they remained employed or quit. The stimulus checks found them, most of them at least, not all of them.

How the stimulus checks succeeded in reaching so many who lost income but failed in reaching everyone who lost income, is vital to understand. The key detail is that the stimulus checks were means-tested for those with high incomes. Those deemed as having too high of income were excluded from the payments. This line was drawn for individuals at $75,000 such that those earning more than that, got less than the full amount, until they earned so much they got nothing. This may sound like common sense. Why provide payments to those with high incomes? Well, the answer is because we only know people’s past incomes, not their present or future incomes.

Because the stimulus checks used earnings data from previous years, there were people who had high incomes, but lost their jobs as a result of the pandemic just like everyone else, and got no stimulus to help them. This is the inherent folly of means-testing - false negatives - where people who should get help and need help don’t pass the test to get help.

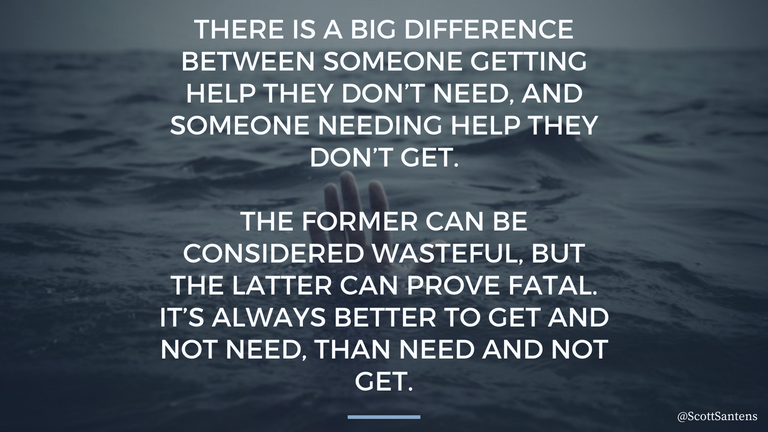

There is a big difference between someone getting help they don’t need, and someone needing help they don’t get. The former can be considered wasteful, but the latter can prove fatal. It’s always better to get and not need, than need and not get.

UBI is a policy that understands this hard truth. Because it is unconditional and universal, the help is always there in advance of even needing it. It’s like falling off a boat with inflatable clothing instead of falling off a boat and screaming for help that may or may not come. It can mean the difference between life and death.

The most important reason for basic income to be fully universal is to acknowledge that any means-testing will always exclude some percentage of those who need it most.

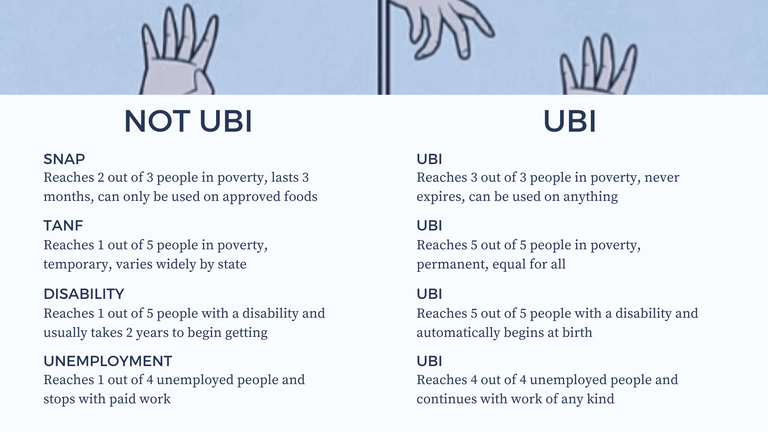

Before the pandemic even hit, 13 million Americans were living in poverty entirely disconnected from all federal assistance programs. The best functioning program is our food assistance program which reaches 2 out of 3 people in poverty, and lasts for 3 months every 3 years. Our worst is our temporary assistance for needy families program which varies by state, and in my home state of Louisiana reaches only 4 out of every 100 families living in poverty. Our disability assistance reaches 1 out of every 5 Americans with disabilities, and the average waiting time to qualify is two years. Our housing assistance reaches 1 out of every 4 Americans who qualify. Our unemployment insurance reached about 1 out of every 4 unemployed people in 2019.

Over and over again, with targeted program after targeted program, our safety net tends to let three out of every four people fall right through it. Because of UBI's universality, zero out of every four people would be excluded from assistance, because they'd already have it, and many wouldn't even need any additional assistance beyond their UBI, because it would provide more than many existing supports even offer. Many programs would simply become unnecessary or at least less necessary with UBI operating as a foundational income floor underneath everyone.

And for those who need more than the UBI, like for example those with disabilities, at least they would have that floor while they go through the process of qualifying for extra assistance, instead of having nothing until they qualify.

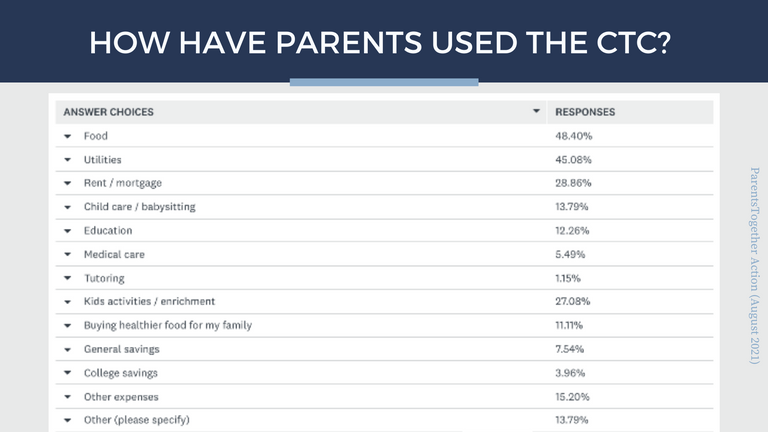

There’s one more program besides the unemployment boost and stimulus checks that the US did and it’s the closest thing to UBI we’ve done yet, and that’s the fully refundable child tax credit payment or CTC which went to most families with kids starting in July of 2021 and ended at the end of 2021. It lacked any work requirements. All low- and middle-income parents qualified for it regardless of how little income they earned. This new monthly cash payment per child, a kind of basic income for kids, resulted in a substantial drop in child poverty with an estimated 4 million fewer kids living in poverty while the checks were going out.

Here’s how parents spent the monthly CTC. The payments helped parents buy things like food and school supplies for their kids, and proved especially helpful during a time of higher inflation that most of the world is still feeling as a result of the pandemic and its impact on global supply chains. Multiple surveys have also shown that the CTC actually led to many parents being able to work more hours of employment by helping them afford childcare. The payments also reduced stress, lowered debt, built savings, and improved mental health.

I’m looking forward to all the studies that will be published about the economic impacts of the CTC. My guess is that the impacts will look a lot like Canada’s Child Benefit which is quite similar in size and design, and which has been measured as adding $2 in GDP for every $1 distributed to parents, and is responsible for 2.5% of Canada’s labor force through the jobs created and supported by parents spending it every month there.

Now that I’ve covered the three major economic responses to Covid in the US that have the most to contribute to the UBI discussion, there’s something else I would like us all to consider besides Covid, and that’s climate change and its impacts on our everyday lives right now and in the future. I say this as someone living in New Orleans, who recently had to evacuate my home and stay evacuated for ten days because of a hurricane that knocked out the power to my entire city: basic income is about resilience and adaptation.

When it comes to evacuating for hurricanes, the biggest reason people don’t evacuate is because they can’t afford to. Gas costs money, that is if people even have a car. Hotels cost money. Eating out while away from home costs money. People need money to be able to respond to climate emergencies like hurricanes, flooding, and wildfires. People need to be able to afford to reach higher ground, both physically and metaphorically.

Also consider how cash can be anything, and how useful that is in emergency situations. When I returned from my evacuation, my wife and I stopped at a store along the way to buy some groceries to restock our fridge that had lost power for a week. The store we stopped at was only able to accept cash. The machines that accepted government food assistance were down. Had we not had cash and instead relied on that assistance, we would have left that grocery store without food. That’s the reality for many people receiving government benefits that aren’t cash. Sometimes even when you have it, you can’t even use it. As the saying goes, cash is king.

We, as in all of humanity, need to do a better job of making sure that we better protect each other from disasters. We need to better help each other escape dangers and become more resilient to the disasters that can befall any one of us, at any time, poverty included. And the best way to help is always in advance, not after something happens, but before it happens. UBI is how to achieve that. It’s an ounce of prevention instead of a pound of cure.

This thinking should also be applied to the automation of labor. We shouldn’t wait until robots end enough jobs for it to be seen as a problem. In fact, automation should never be seen as a problem at all. It should be seen as a benefit to all of society. UBI is how to make automation literally work for all of us, and it should be seen as a dividend accrued through centuries of technological growth that we inherited from all the generations before us.

It’s not a problem that robots take human jobs. The problem is humans requiring humans to have jobs, especially when many of those jobs can be entirely unnecessary or even harmful, socially or ecologically, and when the entire point of automation is to enable humanity to do more with less.

So now that you have a better understanding of UBI and some of its effects and potential, especially in the face of global crises like pandemics and climate breakdown, you may be wondering how to really make it happen. You understand it as an investment now, that can yield more in savings and benefits than it costs, but how can it actually be done?

First and foremost, most countries are already doing a great many things that could fairly easily become UBI if not for all the conditions, means-testing, benefits-in-kind, and tax subsidies they currently insist upon doing instead. For example, many countries choose to use tax allowances where people aren’t taxed until they earn a minimum amount of money. An alternative to that would be a UBI floor instead, where a percentage of every dollar earned on top of the UBI is taxed, either directly or indirectly.

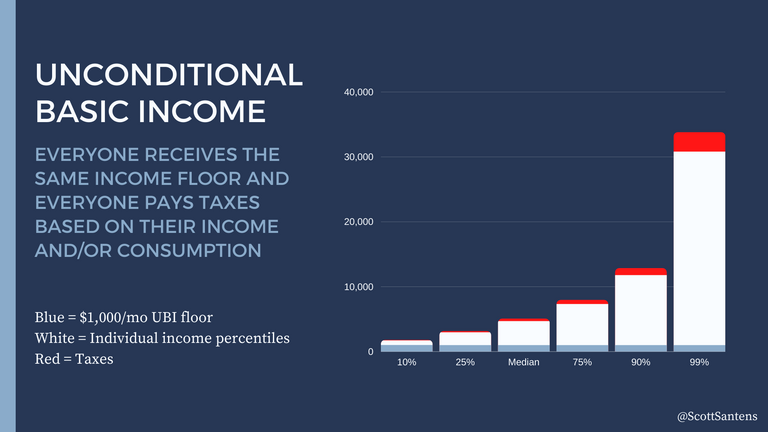

Second, don’t think of money going to those with higher incomes as wasteful. What’s wasteful is not realizing that it’s a waste of time and money to try to target based on need. Targeting should be accomplished through taxes, because that process already exists. If you don’t want billionaires to receive a disposable income boost with UBI, then just increase their taxes more than the amount of UBI they receive. Understand that because UBI is paired with taxes, there will always be those who receive more in UBI than they pay in taxes, while others pay more in taxes than they receive in UBI. That point where someone pays the same in taxes as they receive in UBI is the threshold to focus on in designing a UBI.

Third, the cost of basic income is never the gross cost. It’s never as simple as just multiplying the amount of UBI by the number of recipients. The cost is the net cost which is the difference between what people receive in UBI and what they pay in taxes. The simplest way to understand this is to imagine providing everyone a million dollars and then applying a tax of a million dollars so that no one gained or lost any money than they originally had. The cost of that is zero, not $1 million times the number of recipients. What matters is the new allocation of income compared to the old allocation of income after UBI and taxes are both applied.

Fourth, there is nothing more costly than spending time and resources entirely unnecessarily. As long as poverty exists, that is extremely expensive and is actively requiring all kinds of time and resources to very wastefully treat the avoidable results of it. The cost of UBI is never just about UBI, but about all the time and resources that no longer need to go to the impacts of maintaining a society without UBI.

Any economist who says UBI is too expensive and yet has never attempted to estimate the full costs of poverty, extreme inequality, and chronic insecurity, is as worth listening to as a doctor who says vaccinating everyone is too expensive despite being surrounded by crowded hospitals full of the unvaccinated. Always consider the overall, big picture, total cost.

Consider too, the big picture costs that go far beyond economics. Authoritarianism is on the rise around the world, including in the US. Why? There appears to be a loss of confidence and trust in institutions, and that trust is necessary to hold society together. People need to know that governments can really work for them to meet their very real needs, and trust them to make their own choices in order for people to trust their governments in return. As long as trust continues to erode instead of grow, the social contract itself is at risk of collapse. This isn’t just about money. This is about the success or failure of the institution of government itself.

Fifth and also finally, I want to leave you with one more thing. Money isn’t real. It’s a tool we created. Tools are meant to serve us, not limit us. There is no limit to the amount of money humans can create. There are however limits to what we can accomplish based on time, resources, people, technology, knowledge, and will. And it’s that last one that seems to be the most scarce of all. No country has adopted UBI yet because of any other real reason but a lack of will. It’s a choice to keep a minimum amount of money from people’s hands. It’s a choice based on all kinds of long-term societal hangups like distrust of others, fear, racism, and the desire for power and control over others.

At its heart, UBI is about freedom, power, and trust. As long as people lack what they need to live, and must do what others tell them to in order to survive, that is a lack of power and freedom. And as long as we are afraid of granting each other the power to truly set our own destinies by way of our own free choices, we have a civilization built on distrust. I don’t think that kind of civilization is going to make it. We are all interdependent. We all need each other, and we should start treating each other that way, by trusting each other, without conditions, with what we all need to live.

We are all equally worthy of existing. That’s unconditional basic income.

Think people with UBI will stop working or that it will lead to inflation? Here's a list of answers to those and other frequently asked questions.

Did you enjoy this article? Please subscribe to my blog (it's free!) and also consider making a small monthly pledge in support of my ongoing UBI advocacy work. You can also buy my book to learn more about just how affordable and necessary unconditional basic income actually is.

.jpg)