Outside, the locality is pin-drop silent. It is a setting enveloped in shyness, not timidity. A massive grassland is infested with moths, termites and others. Spread over it like groundnut paste over a slice of bread is a grazing flock of cattle, multicoloured in a staggering mosaic. Above the flock is a multitude of birds chirping melodiously, sometimes almost in chorus, and picking feed. Soon as the sun kisses the western horizon to set, the landscape is a priceless sight. Even Leonardo Da Vinci will drool admiring it.

On the other side is a river flanked by irrigable land. It is adorned with farms of vegetables. In the farm are footpaths dividing it into various shapes and angles - a scene an aerial view will do justice to. The river is rich in sea food, abundant of which is fish. Fishing becomes an inevitable side engagement for farmers. Hook and line as well as nets are good to go with. At times in the evenings, laying the nets in ambush requires a pretty risky-looking spectacle. It sees the fisher go mid-sea to plant his net, often leaving only his head above water.

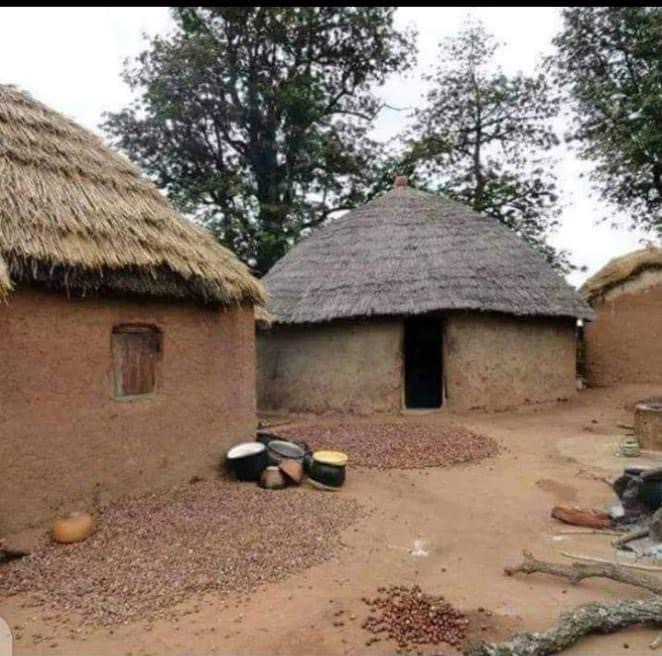

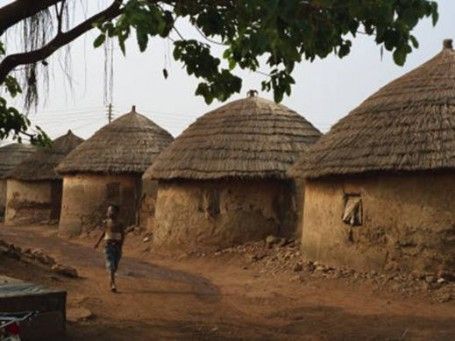

Back home, the village settlement is either nucleated or dispersed and overlooked by baobab or kapok trees. Huts are separated by small and short walls, with provision made for a main entrance that is either closed by a wooden gate or sometimes not at all. Most often, the middle of the compound is the kitchen. Stones are placed in clustered threes for cooking and a hut normally reserved as storage for food items. In some instances, a smaller hut is made for poultry keeping or for livestock. By the entrance of the family head's room is a collapsible chair, on which he sits to engage his household.

Wives do not fret in getting their duties done. They have the compound to dry their flour, shea nuts, grains and others. Child upbringing in settings like this is lacking in nothing. The household is a college of education for morals and values. Parenting is carried out with obligation, as if to suggest an instant curse awaits the parents if absent. Chores are for everyone, boy is girl. Children raised here are adept with farmwork and cooking. With the latter, girls are clearly given preference for obvious reasons. Children are taught to respect and honour the elderly.

Illiteracy is not the preserve of rural folk. They go to school and excel. They land gainful, white-collar employment and carve entrepreneurial employment for themselves in contributing to national productivity. Indeed, their story is littered with severe lows that are unheard of in the other divide; from a possible initial resolve not to be sent to school to lack of uniforms and books to being sacked for not paying school fees to dropping out for farmwork when the rains arrive to being married out. Nonetheless, they survive the tides and swim ashore.

So, what do rural settings really lack? Internet? Yes, but they do not need it. It has no significance to their life fabric. Electricity? Yes, because it will enhance their lives and livelihoods, just like everyone else. Portable water? Yes, because they are not supposed to drink contaminated water, just like everyone else. Healthcare? Yes, because they fall sick and need treatment, just like everyone else. Schools? Yes, because their children need quality education, just like other children. They are deserving of all life essentials.

Knowledge and wisdom find home in people, irrespective of where they live or come from. Great intellectuals often emerge from deprived places. They are the legends. Their stories inspire more because of humble beginnings. Village life is not a drawback. It is often a springboard to hit heights. After all, in the village there is no traffic, no noise, no pollution. That alone is enough.