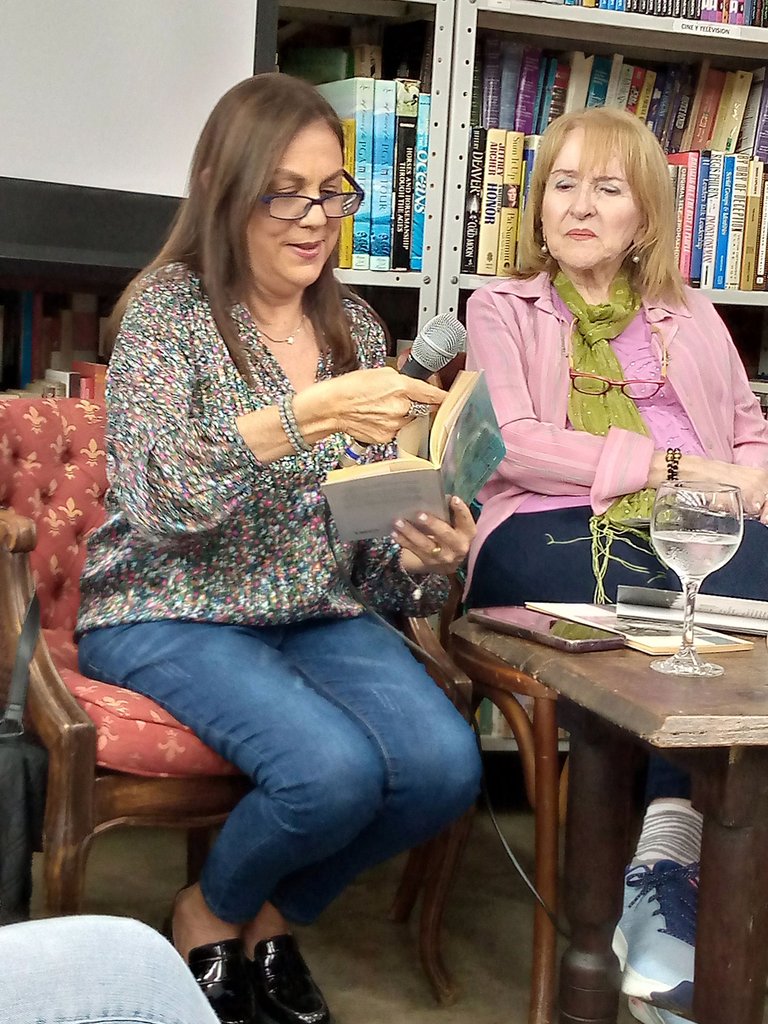

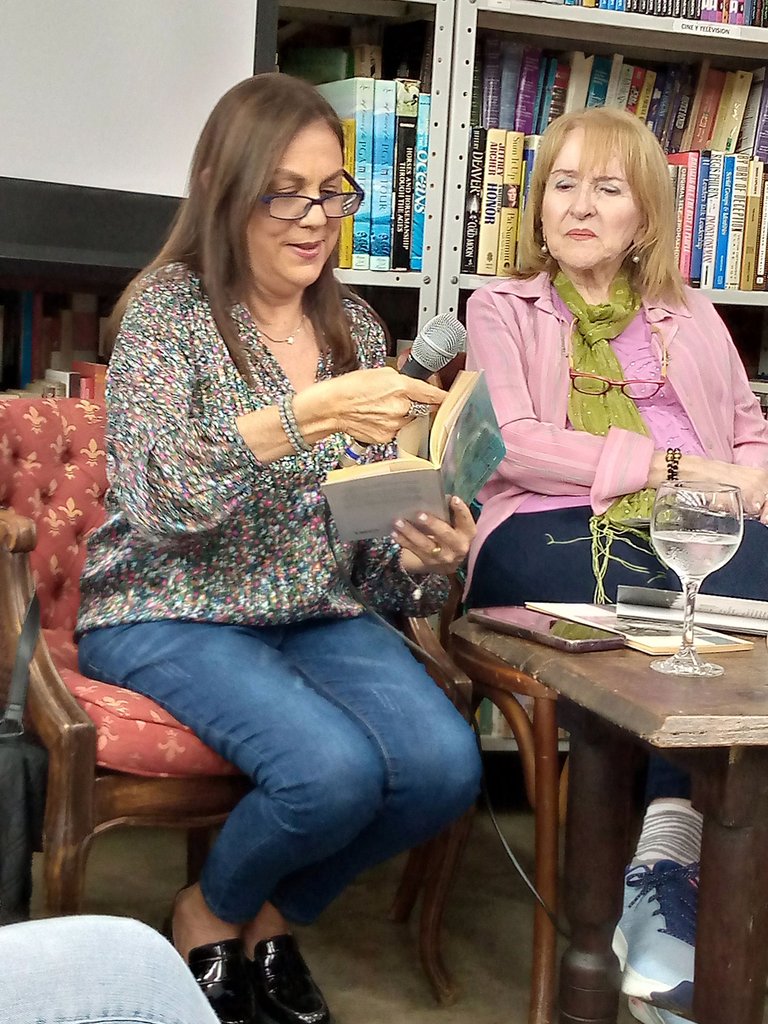

Recientemente estuvo en Caracas la poeta y educadora venezolana Victoria Benarroch, quien actualmente está residenciada en Panamá. La poeta Carmen Cristina Wolf, Secretaria del Círculo de Escritores de Venezuela, organizó un homenaje para ella en la librería Kalathos, ubicada en Los Galpones de Los Chorros. Tuve el privilegio de participar en el evento y profundizar en la lectura de su poesía. En los últimos 20 años no son pocos los poetas venezolanos que han tomado la decisión de migrar. Pero felizmente algunos nos visitan, mantienen un vínculo con su país de origen.

Victoria es de origen judío, un pueblo que por diversas razones ha sido migrante a través de su historia milenaria. Su madre nació en Casablanca, Marruecos, pero con apenas dos años de edad llegó con su familia a Venezuela, en 1939, el año que comenzó la Segunda Guerra Mundial, en uno de los barcos que el gobierno de Eleazar López Contreras dejó entrar al país. Su padre, nació en la ciudad de Melilla, donde vivió hasta los cinco años y luego vivió entre Tanger yTetuán hasta los 16 años, cuando migra a Caracas. El viajar y el mantener sus tradiciones forman parte de la cultura judía.

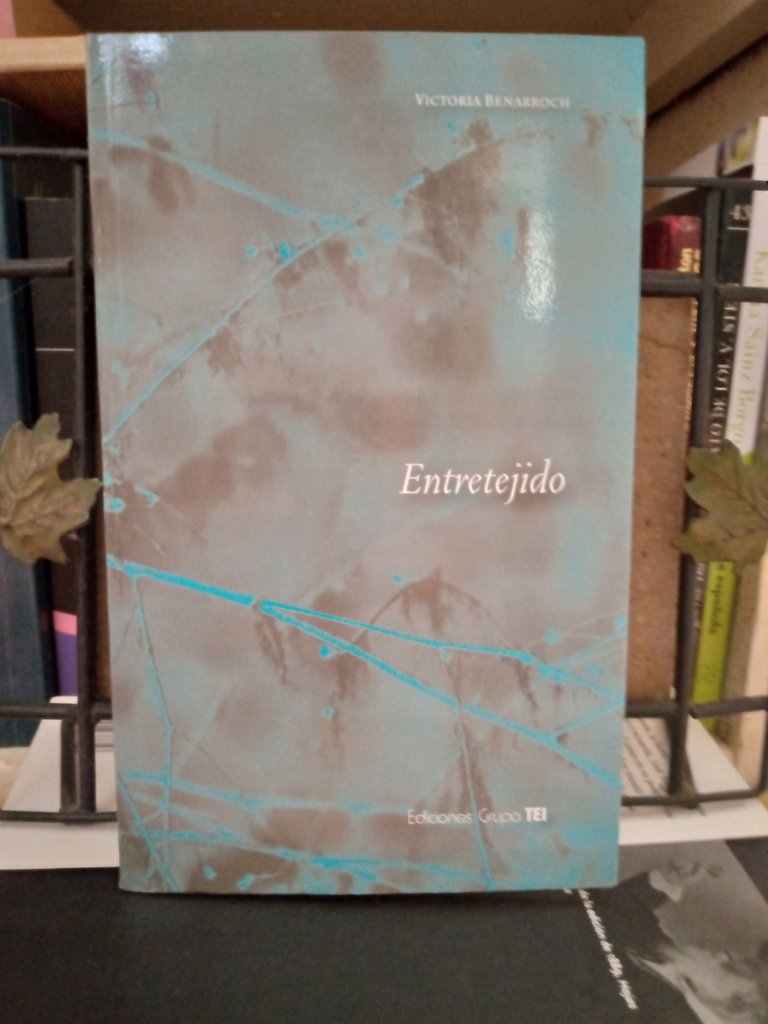

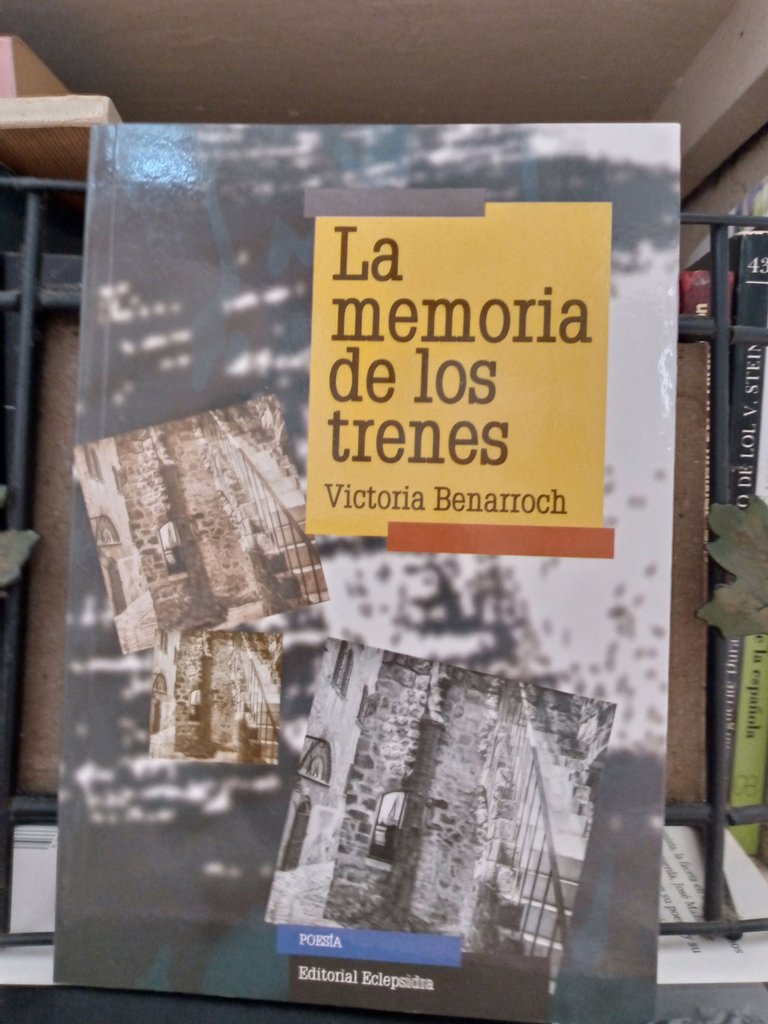

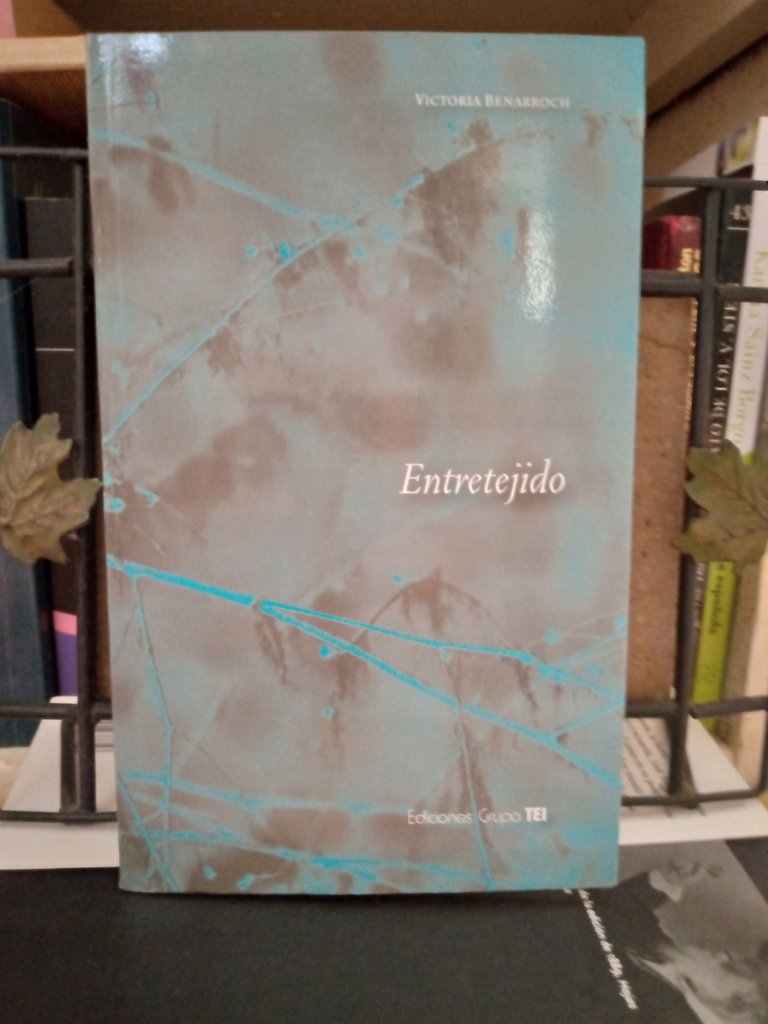

Le pregunté a qué edad había comenzado a escribir y me contestó que a los 13 años escribió un poema, luego a los 16 años empezó a escribir diarios, pero fue en 1998 cuando comenzó a escribir con más regularidad y en el 2000 envió algunos poemas a la Fundación Celarg y fue aceptada para participar en el taller de poesía que dirigió la poeta y ensayista María Antonieta Flores. La poeta, nacida en Caracas en 1962, es educadora, mención Preescolar y hasta el momento ha publicado dos libros de poesía: “Entretejido” publicado en 2007 por Editorial Eclepsidra y reeditado en 2015 por Ediciones Grupo TEI y “La memoria de los trenes”, editado también por Ediciones Eclepsidra.

Entretejido

Entretejer, nos dice el diccionario de la Real Academia Española, es insertar en una tela que se teje hilos diferentes para que hagan distinto dibujo; este verbo podemos vincularlo con los verbos trenzar, urdir, entrelazar. En el libro que nos ofrece Victoria Benarroch se entrelaza con hilar en la memoria ancestral, valorar como herencia lo que se recibe de los ancestros, los padres, los abuelos, es el tema medular de su primer libro. La poeta señala en el brevísimo texto que inicia la parte del libro titulada “Del cofre”, que es allí donde se ancla su voz, en esa memoria ancestral que ha devenido en refugio:

a María Cristina Ashworth

La memoria guarda un refugio allí permanece mi voz

El libro está conformado por cinco partes: “Con la tinta en la niebla”, “Del cofre”, “De la limosna”, “Yo en casa” y “Las palabras de mi padre”. En medio de un camino incierto, la memoria de lo que ha sobrevivido milenios pareciera sostener la propia identidad, pero también el afecto, la cercanía de los seres amados que le han transmitido ese legado. Porque ese legado no es una abstracción, se recibe y luego se entrega a las nuevas generaciones en los rituales del día a día, en las fiestas de guardar.

Así aparecen, entretejidos, a través del libro, algunos elementos simbólicos vinculados a la cultura judía y el homenaje a las figuras familiares. Uno de los referentes que se reiteran especialmente es el muro y las piedras que lo conforman, que podemos vincular con la muralla de Jerusalem, con el muro de los lamentos, y así también con lo sólido, con lo que perdura en el tiempo. Y así me lo confirmó la poeta cuando se lo pregunté:

En la cultura judía es el muro del templo destruido de Jerusalem. El muro que quedó, la memoria de lo que se ha de construir de nuevo. El lugar donde pedimos al todopoderoso, pero el muro que permanece está en cada uno de nosotros. El muro es lo que no se destruye. La piedra como la permanencia de la memoria. La unión entre lo espiritual y lo físico. La piedra es duradera, es lo inmutable con el paso del tiempo.Fuerza interior.

Así vemos la piedra y el muro como un referente que se reitera y se entrelaza con la conformación de la voz poética y de esa fortaleza interior, es la nostalgia de lo perdido, lo destruido, pero también la esperanza, la fe en lo que puede reconstruirse, aún en medio del desierto, del peregrinar a través del desierto:

“La mudez/traslada la piedra/que espera ser hallada” (p.33)

“Las piedras me trasladan a la tierra prometida

Mis padres cada año en pascuas dicen lo mismo

creciendo con la añoranza de encontrar

un color que me lleve al muro” (p.34)

La familia, los ancestros, son quienes ayudan a configurar ese camino que lleva al muro, a lo que permanece, a lo imperecedero. Así cierra el poema dedicado a su abuelo José Benatar expresando “su voz permanece en la mía” (p.37) y ante la pérdida y la lágrima entregaba “algún beso de sabiduría”. Mientras que en el poema dedicado a la abuela dice: “Y cuando las líneas de mi mano recorran los siglos/un espejo desde el fondo surgirá a rescatarme” (p. 39). El espejo aquí es símbolo de esa herencia que en la cultura judía transmite es la madre, quien la entrega a los hijos. Así, en el poema dedicado a la madre, Vera Benarroch Benatar, se reitera la imagen del cuido, del resguardo: “no hallo el perfume de sus manos/los bordes más tibios protegen”.

La memoria de los trenes

El tren en su movimiento nos aleja de un lugar, pero nos acerca a otro, en su segundo libro Benarroch indaga nuevamente en esa herencia recibida de sus mayores; memoria en la que se entrelazan recuerdos de personas, lugares y paisajes perdidos, el dolor que genera esa pérdida; pero también hace referencia a una fortaleza y unión que en medio del desierto y de la pérdida es capaz resurgir entre las cenizas, como el ave fénix, y renacer, ofreciendo un legado de amor para las nuevas generaciones.

En “La memoria de los trenes” la voz lírica se presenta en uno de los primeros poemas como mujer, “una mujer nombra la vida//es una gota que besa/el espíritu del que la sueña” (p. 11). La mujer es raíz, aún en el peregrinar, aún en medio de la violencia, de lo que ha sido destruido: “Tu voz de raíz/ hundida en la tierra/ te reduce entre los arbustos/ que añoran la calma” (p. 14) (...) “tu cabellera es fronda/ y tus raíces más fuertes/ que la palabra a la que te redujo”. (p.16)

En su segundo libro el paisaje, los árboles particularmente, es un referente que la poeta vincula con lo vivo y con lo afectivo (“un tronco le dice a mis manos/que no están solas” (p.28)). Al crecer protegen, dan sombra y la poeta los presenta como parte de esa memoria heredada, que aunque marcada por el desarraigo, la migración, también logra encontrar raíz, anclaje, en el amor: “un ciprés es un presagio/ funda caricias// sus tallos saben de misterios” (p. 25) (...) “una semilla/ transita toda la tierra/ deleitada en su sed/ ilumina/ el vuelo de amar/ lugares de nostalgias/ y a esa tristeza/ que no deja de acompañarme” (p. 49)

Al igual que otros poetas venezolanos que han migrado encontramos en este libro referencias explícitas al tema de la migración, pero en este caso el peregrinar forma parte de una herencia cultural, de los ancestros judíos. Victoria expresa en el poema “De la culpa”: “Cuando partir era deshacer los astros/ su sed/ dejó aire en mi pecho// y él en esa esquina tuya” (p. 15). En “De dejar ir” nos dice: “Emigrar/ mirar su doblez/ su superficie ondulante/ que habita y crea/ antes de la partida/ el instante/ donde existe la serenidad” (p.20). La serenidad, la paciencia de la gestación, pareciera la búsqueda de esa voz que habla, esa “mujer triste/ que miraba por la ventana/ al encuentro fortuito de las estrellas/ que esperaban/ desde hace siglos su palabra”. (p.29)

Bibliografía consultada:

Benarroch, Victoria. (2015, segunda edición). Entretejido. Caracas: Ediciones Grupo TEI.

Benarroch, Victoria. (2015). La memoria de los trenes. Caracas: Editorial Eclepsidra.

Las fotos fueron tomadas con la cámara de mi teléfono móvil

Venezuelan poet and educator Victoria Benarroch, who is currently living in Panama, was recently at Caracas. The poet Carmen Cristina Wolf, Secretary of the Venezuelan Writers' Circle, organised a tribute to her at the Kalathos bookshop, located in Los Galpones de Los Chorros. I had the privilege to participate in the event and to read her poetry in depth. In the last 20 years, more than a few Venezuelan poets have decided to emigrate. But fortunately some of them visit us, maintaining a link with their country of origin.

Victoria is of Jewish origin, a people who for various reasons have been migrants throughout their millennia-long history. Her mother was born in Casablanca, Morocco, but when she was barely two years old she arrived with her family in Venezuela in 1939, the year World War II began, on one of the ships that the government of Eleazar López Contreras allowed to enter the country. His father was born in the city of Melilla, where he lived until he was five years old and then lived between Tangiers and Tetouan until he was 16, when he migrated to Caracas. Travelling and maintaining their traditions are part of the Jewish culture.

I asked her at what age she had started writing and she replied that at 13 she wrote a poem, then at 16 she began to write diaries, but it was in 1998 when she began to write more regularly and in 2000 she sent some poems to the Celarg Foundation and was accepted to participate in the poetry workshop directed by the poet and essayist María Antonieta Flores. The poet, born in at Caracas in 1962, is an educator, mention Preschool and has so far published two books of poetry: ‘Entretejido’ published in 2007 by Editorial Eclepsidra and republished in 2015 by Ediciones Grupo TEI and ‘La memoria de los trenes’, also published by Ediciones Eclepsidra.

Interweaving

To interweave, according to the dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy, is to insert different threads into a fabric that is being woven so that they make a different pattern; this verb can be linked to the verbs trenzar, urdir, entrelazar. In the book that Victoria Benarroch offers us, it is intertwined with spinning in the ancestral memory, to value as an inheritance what is received from the ancestors, parents, grandparents, is the central theme of her first book. The poet points out in the very brief text that begins the part of the book entitled ‘Del cofre’, that it is there where her voice is anchored, in that ancestral memory that has become a refuge:

to María Cristina Ashworth

Memory keeps a refuge where my voice remains

The book is made up of five parts: ‘With ink in the fog’, ‘From the chest’, ‘From alms’, ‘Me at home’ and ‘My father's words’. In the midst of an uncertain path, the memory of what has survived millennia seems to sustain one's own identity, but also the affection, the closeness of the loved ones who have passed on that legacy. Because this legacy is not an abstraction, it is received and then passed on to the new generations in the rituals of everyday life, in the festivities.

Thus, interwoven throughout the book are certain symbolic elements linked to Jewish culture and homage to family figures. One of the references that is especially reiterated is the wall and the stones that make it up, which we can link to the wall of Jerusalem, to the wailing wall, and thus also to what is solid, to what endures over time. And this is what the poet confirmed when I asked her about it:

In Jewish culture it is the wall of the destroyed temple in Jerusalem. The wall that remains, the memory of what is to be built again. The place where we pray to the Almighty, but the wall that remains is in each one of us. The wall is that which is not destroyed. The stone as the permanence of memory. The union between the spiritual and the physical. The stone is durable, it is that which is immutable with the passage of time. Inner strength.

Thus we see the stone and the wall as a reference that is reiterated and intertwined with the shaping of the poetic voice and of that inner strength, it is the nostalgia for what has been lost, for what has been destroyed, but also hope, faith in what can be rebuilt, even in the midst of the desert, of the pilgrimage through the desert:

‘The dumbness/ moves the stone/ that waits to be found’.(p.33)

‘The stones take me to the promised land.

My parents say the same thing every Easter every year

growing up with the longing to find

a colour that will take me to the wall’. (p.34)

The family, the ancestors, are the ones who help to shape the path that leads to the wall, to what remains, to what is imperishable. Thus he closes the poem dedicated to his grandfather José Benatar by expressing ‘his voice remains in mine’ (p.37) and in the face of loss and tears he delivers ‘some kiss of wisdom’. While in the poem dedicated to her grandmother she says: ‘And when the lines of my hand run through the centuries/ a mirror from the depths will emerge to rescue me’ (p. 39). The mirror here is a symbol of that inheritance which in Jewish culture is transmitted by the mother, who gives it to her children. Thus, in the poem dedicated to the mother, Vera Benarroch Benatar, the image of care, of protection, is reiterated: ‘I cannot find the perfume of her hands/the warmest edges protect’.

The memory of trains

The train in its movement takes us away from one place, but brings us closer to another. In his second book, Benarroch once again explores this inheritance received from his elders; a memory in which memories of lost people, places and landscapes are intertwined, the pain generated by this loss; but he also refers to a strength and union that in the midst of the desert and loss is capable of rising from the ashes, like the phoenix, and being reborn, offering a legacy of love for new generations.

In ‘The memory of trains’ the lyrical voice is presented in one of the first poems as a woman, ‘a woman names life//it is a drop that kisses/the spirit of the one who dreams it’ (p. 11). The woman is a root, even in the wandering, even in the midst of violence, of what has been destroyed: ‘Your root voice/ sunk in the earth/ reduces you among the bushes/ that yearn for calm’ (p. 14) (...) ‘your hair is frond/ and your roots stronger/ than the word to which it reduced you’ (p. 16).

In her second book the landscape, trees in particular, is a reference that the poet links to the living and the affective (‘a trunk tells my hands/that they are not alone’ (p.28)). As they grow they protect, give shade and the poet presents them as part of that inherited memory, which although marked by uprooting, migration, also manages to find root, anchorage, in love: ‘a cypress is an omen/ it founds caresses// its stems know of mysteries’ (p. 25) (...). 25) (...) ‘a seed/ travels all over the earth/ delighted in its thirst/ illuminates/ the flight of love/ places of nostalgia/ and that sadness/ that never ceases to accompany me’ (p. 49).

Like other Venezuelan poets who have migrated, we find in this book explicit references to the theme of migration, but in this case the pilgrimage is part of a cultural heritage, of Jewish ancestors. Victoria expresses in the poem ‘Of guilt': “When to leave was to undo the stars/ his thirst/ left air in my chest// and he in that corner of yours”. (p. 15). In ‘On letting go’ he tells us: ‘To emigrate/ to look at its fold/ its undulating surface/ that inhabits and creates/ before departure/ the instant/ where serenity exists’ (p.20). Serenity, the patience of gestation, seems to be the search for that voice that speaks, that ‘sad woman/ who looked out of the window/ at the fortuitous encounter of the stars/ that have been waiting/ for centuries for her word’ (p.29).

Bibliography consulted:

Benarroch, Victoria. (2015, segunda edición). Entretejido. Caracas: Ediciones Grupo TEI.

Benarroch, Victoria. (2015). La memoria de los trenes. Caracas: Editorial Eclepsidra.

Translation to english by Deepl.com

The photos were taken with my mobile phone camera.

Esta publicación ha recibido el voto de Literatos, la comunidad de literatura en español en Hive y ha sido compartido en el blog de nuestra cuenta.

¿Quieres contribuir a engrandecer este proyecto? ¡Haz clic aquí y entérate cómo!

Muchas gracias por el apoyo, amigos de @es-literatos.

Sabio tu acercamiento a Victoria y su poesia. Sus versos son muy humanos y sinceros ..

Muchas gracias por tu lectura y tu comentario @pinero. Un abrazo desde Caracas, Venezuela.

@tipu curate 8

Upvoted 👌 (Mana: 0/66) Liquid rewards.

Muchas gracias por el apoyo.

Bella la poesía de Victoria Benarroch, de hondo sentido humano, tocada por la memoria y lo ancestral, sin duda. Gracias por compartir tu interpretación de sus dos libros, con esos fragmentos de ellos. Saludos, @beaescribe.

Muchas gracias por tu lectura y comentario, estimado @josemalavem