Writing is an act of rebellion against reality, said Mario Vargas Llosa, and when I read the 2022 Santa Clara City Prize Neighborhood Chronicles by Jorge Luis Mederos (better known as Veleta), I couldn't help but think: this is a rebellious book. This is a real award!

Published by Editorial Capiro in 2023 and presented in 2024, I think this is a book that will transcend history. Not only in the history of Condado, nor that of Santa Clara, but it will become a snapshot of the less fortunate neighborhoods, the marginalized ones, any neighborhood in Cuba today. Like a personal Macondo, Veleta portrays various scenes from his neighborhood (your neighborhood, mine) at every moment of the day (Morning, Afternoon, and Night). He portrays them the same way he SEES them. Thus, in capital letters. Because it's not just "seeing" with the eyes, but goes beyond. It's seeing with the soul, with the body, with pain.

Neighborhood Chronicles is a beautiful book written in a tone of dirty realism.

It's a book of love.

It's a compilation of raw, sincere texts, written from a critical perspective and the sense of belonging of a son of that neighborhood. A Cuban neighborhood, a universal neighborhood, and for that reason, I don't think there's a better way to write it than with décimas.

Cuban décimas are so ideal for humor, denunciation, and love. Décimas that, by their very musical nature, give the lyrics greater beauty and greater depth to the message.

This is a book of love, in every sense of the word. Verse by verse, Veleta described his beloved neighborhood and stripped it garment by garment, kissing its bare skin and its scars.

How can it be a beautiful book written in dirty realism? How can the association of dirt with beauty be conceived? Words like disgust, death, dump, shit, in something beautiful? You might ask, and the best answer was given to me one day by the young writer Eduardo Daniel Rosell Herrera:

“Veleta is a true poet. That's why he is.”

His point of view is unquestionable, and there is no better way to respond.

Chronicles of the Neighborhood is a Cuban book, written in a Cuban way, that captures every element of our culture. Veleta begins the book with a heartfelt prayer (as a prologue) to the Virgin of Charity, mother of all Cubans, and these verses alone, this image alone, are enough for the author to describe the way life is in the neighborhood:

Lower your eyes to the ground

of a broken and withered city

that shares its anguish

with your gaze on the sky.

This is a recurring image throughout the notebook. This is how the book begins before describing "Morning."

Religion, regardless of the religion (although it focuses more on Yoruba and Catholicism), is a recurring element in this section. The prayer already foreshadowed this.

But in this case, it is approached, mostly, from the perspective of those who were abandoned by God in this corner of the world; the uncertainty of God's plans for us mortals. God is omnipresent in the faith of those who suffer, pray, and hope.

The neighborhood is lost, it is lost

of a terrible grayness in the areas

of pain and the people

who with open arms

moan, with deserted eyes:

“Father… why have you abandoned me?”

They are that inseparable duo of God and man… almost as inseparable as man and bread, who also appear in the book as leitmotifs… as characters.

This beautiful chronicle begins in the morning as if the lyrical subject, or the author, had left the house for a walk and were describing everything within reach of his senses: the bread, the puddles, the horses, the dawn, the faith, the games, the incongruities, and, above all, that New Man who has grown up in this (these) neighborhood(s).

Despite being a book written in a fairly straightforward style, there is a very rich use of analogy and situational metaphors, both refined and elegant. This is a frequently used resource, not only in this first part of the Neighborhood Chronicles, but it also appears and enriches the text, giving it those rich levels of interpretation that the intelligent reader appreciates.

The lyrical subject continues walking, and the "Afternoon" falls upon him. He arrives at his house and describes it from there. He does so as if he were looking out the window or sitting on the porch. He invites you into his home. A home that could be that of any Cuban (as in Macondo).

(image courtesy of the author)

“The Afternoon” is perhaps the saddest, rawest, and most painful part of the book. It focuses on the human and economic misery of many.

Cubans are known for their hospitality, for sharing the “little they have.” This is often a euphemism that Veleta uses by name: misery. Thus, the lyrical subject invites you to his house; taking it as a model for the rest of Condado, inviting you with a "crossing under its rubble lintel."

In describing that house, Veleta describes the Cuban people, their idiosyncrasies, the needs of these neighborhoods, the timelessness discovered in 21st-century homes with decorations and furniture from other (perhaps more prosperous) eras. "Better times," some call them.

The lyrical subject looks from his house toward those inhabited by lonely old people, stray dogs, religious festivals (the only moment of apparent joy in the Afternoon), depression, the river, the rain.

In all these titles or literary objects described, one sees that common thread of abandonment, loneliness, violence, and the incessant search for a reason for joy... wherever it may be.

Despite being from Afternoon, this is a gray, melancholic section. Never sunny. Perhaps that's why the author closes it with a poem dedicated to the rain. That element that cleanses, gives life and joy; it is used so masterfully that, like water, the lyrical subject slips through the cracks and reveals those miseries hidden from plain sight.

Night falls in Condado.

To emphasize the darkness, the author begins this third section of the book with a poem dedicated to the terrible and common "Blackout." (An event as timeless as the objects in the houses themselves.)

And from this text, the people in the neighborhood begin to appear more directly. The chronicler describes, from his perspective, their (our) fears, those characters who emerge when the sun sets: the thief, the drunks, the mothers, the cries of newborns, the cars, etc.

But the most striking aspect of this last section are the "tributes," the poems dedicated to people, neighbors of the neighborhood who are important to this author.

Important for various reasons. Luisito reflects those young men we always see sitting on sidewalks, uneducated, with the aspirations of criminals, and dreaming of one day leaving the country.

Yania is the painful memory, the denunciation of those evils prevalent in our society: prostitution and teenage pregnancy. Social evils that affect the entire world and about which we need to talk; to raise awareness.

She is the neighborhood, the legacy

its gross domestic product;

and her child will be the fruit

of another castrated fruit.

Elianet is a very beloved person. Every Cuban has at least one Elianet. A loved one who has left this island to live abroad.

This chronicle is the author's tribute to this specific woman and to everything she represents for the reader.

And the lyrical subject of this notebook closes beautifully, as every chronicle does, summarizing what could be read/seen in this section of the book. A summary of images that reminds us of Teresita Fernández's words in her song "Lo feo."

A summary of those feelings of love, nostalgia, hope, and fears, of the lyrical subject.

Crónicas del barrio is a book written in direct, simple, but never simplistic language. With these poems, metaphors, analogies, and multiple layers of interpretation, it cannot be a simple book. It is not a simple read. Veleta is a master of language, of poetry.

He knows how to transform everyday scenes into complaints, denunciations written with a pen, but that travel like bullets, cutting through the toughest skin, like Sevillian knives.

"Writing is an act of courage," we have been told many times, and this book proves it.

This is a brave book written by a brave man who is not afraid. He is not afraid to return to conventional forms and to say what he feels.

He is not afraid to distance himself from modernisms or fashions; and he travels, like Carpentier, to the seed. He uses the conventional, traditional décima. He returns to those clichés and tragedies that have accompanied (and will accompany) human beings since the beginning of time. He returns to the costumbrist forms, to the romanticism of yesteryear... and updates everything.

He breaks with everything, using the old school to create a new one. He taps into the sentiments of today's New Man.

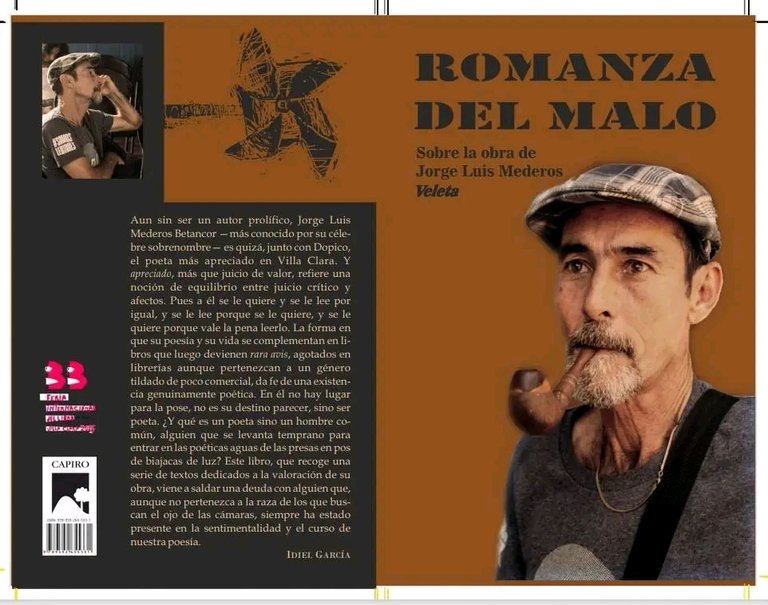

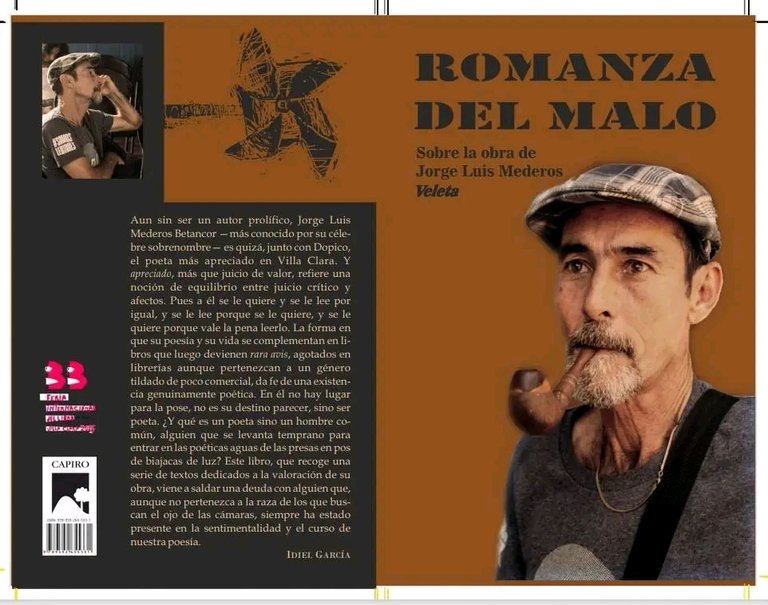

The author doesn't seek to make the form surpass the content, but rather to make the latter the protagonist. Jorge Luis Mederos, "Veleta," seeks and succeeds in ensuring that the reader doesn't get lost in the paraphernalia of embellishments, the contrived form, the gaudy content.

Veleta has dug up, cleared away all the undergrowth, and lets the gold shine on its own. He uses the precise word at every moment, without suggesting or using ambiguities.

Generally, in reviews or critiques, personal assessments should be left aside, but in this case, I cannot and do not want to avoid it.

I wish to leave this in writing: This is a book, an incredible masterpiece. One of those texts we Cubans will return to in 100 years to see, feel, and relive what our neighborhood(s) were like. A snapshot of Cuban reality. Simply put: brutal.

Call a spade a spade, and wine, wine.

Versión en español

Escribir es un acto de rebelión contra la realidad, dijo Mario Vargas Llosa, y cuando leí el Premio Ciudad de Santa Clara 2022 Crónicas del barrio, de Jorge Luis Mederos (más conocido como Veleta) no pude pensar otra cosa que: este es un libro rebelde ¡Este es un premio de verdad!

Publicado por la Editorial Capiro en el 2023 y presentado el 2024, pienso que este es un libro que trascenderá en la historia. No solo en la historia del Condado, ni la de Santa Clara, sino que pasará a ser una fotografía de los barrios menos favorecidos, los marginales, barrios cualquiera de la Cuba de hoy.

Como en un Macondo personal, Veleta retrata varias escenas de su barrio (tu barrio, el mío) en cada momento del día (Mañana, Tarde y Noche). Las retrata del mismo modo en que las VE. Así, en mayúsculas. Porque no es el “ver” solo con los ojos, sino que va más allá. Es ver con el alma, con el cuerpo, con el dolor.

Crónicas del barrio es un libro hermoso escrito en tono de realismo sucio.

Es un libro de amor.

Es una compilación de textos crudos, sinceros, escritos desde una mirada crítica y el sentido de pertenencia de un hijo de ese barrio. Barrio cubano, barrio universal y por esa razón no creo que hubiera una mejor forma de escribirlo que con décimas.

Las décimas cubanas tan ideales para el humor, la denuncia y el amor. Las décimas que, por su propia naturaleza musical, le otorgan mayor belleza a los textos; mayor profundidad al mensaje.

Este es un libro de amor en todas las de la ley. Verso a verso Veleta fue describiendo a su amado barrio y lo desvistió prenda por prenda; besándole la piel desnuda y sus cicatrices.

¿Cómo que es un libro hermoso escrito en realismo sucio? ¿cómo se concibe la asociación de lo sucio con lo hermoso? ¿palabras como asco, muerte, vertedero, mierda, en algo bello?, se podrán preguntar y la mejor respuesta me la dio un día el joven escritor Eduardo Daniel Rosell Herrera:

“Es que Veleta es un tronco de poeta. Por eso es”.

Su punto de vista es incuestionable y no hay otra mejor forma de responder.

Crónicas del barrio es un libro cubano y escrito a lo cubano donde se plasma cada elemento de nuestra cultura. Veleta inicia el libro con una sentida plegaria (a modo de prólogo) a la Virgen de la Caridad, madre de todos los cubanos y solo con estos versos, solo con esta imagen basta para que el autor describa el modo en que se vive en el barrio:

Baja tus ojos al suelo

de una ciudad rota y mustia

que te comparte su angustia

con la mirada en el cielo.

Esta es una imagen recurrente a lo largo del cuaderno. De esa forma inicia el libro antes de describir la “Mañana”.

Lo religioso, sea de la religión que sea, (aunque se enfoca más en la yoruba y católica) es un elemento recurrente en esta parte. La plegaria ya nos lo anunciaba.

Pero en este caso es abordado, mayormente, desde el punto de vista de aquellos que fueron abandonados por Dios en este rincón del mundo; la incertidumbre de los planes de Dios para con nosotros los mortales. Dios omnipresente en la fe del que padece, pide y espera.

Se pierde el barrio, se pierde

de un gris terrible en las zonas

del dolor y las personas

que con los brazos abiertos

gimen, con ojos desiertos:

“Padre… ¿por qué me abandonas?”

Son esa dupla inseparable de Dios y hombre… casi tan inseparable como el hombre y el pan, las que también aparecen presentes en el libro como leitmotiv… como personajes.

Esta hermosa crónica comienza en la mañana como si el sujeto lírico, o el autor, hubiera salido de la casa a caminar y describiera todo al alcance de sus sentidos: el pan, los charcos, los caballos, el amanecer, la fe, los juegos, las incongruencias y, sobre todo, a ese Hombre Nuevo que ha crecido en este (estos) barrio(s).

A pesar de ser un libro escrito en un estilo bastante directo, hay un uso muy rico de la analogía y las metáforas de situación, bien fino y elegante. Este es un recurso muy empleado, no solo en esta primera parte de las Crónicas del barrio, sino que aparece y enriquece al texto dándole esos niveles de lectura tan ricos que agradece el lector inteligente.

Sigue caminando el sujeto lírico y cae la “Tarde” sobre él. Llega a su casa y describe desde ella. Lo hace como si observara de la ventana o sentado en el portal. Te invita a su hogar. Un hogar que podría ser el de cualquier cubano (como en Macondo).

(imagen cortesía del autor)

“La Tarde” es, quizás, la parte más triste, cruda y dolida del libro. Esta se enfoca en la miseria humana y económica de muchos.

El cubano es conocido por su hospitalidad, por compartir lo “poco que tiene”. Esto es, muchas veces, un eufemismo que Veleta menciona por su nombre: miseria. Así que el sujeto lírico te invita a la suya; tomándola como molde del resto del Condado, invitándote con un “cruce bajo su dintel de escombros”.

Veleta, al describir esa casa, describe al cubano, su idiosincrasia, a la necesidad de estos barrios, a la intemporalidad que se descubre en hogares del siglo 21 con adornos y muebles de otras épocas (quizás más prósperas). “Tiempos mejores”, algunos le llaman.

El sujeto lírico mira desde su casa hacia esas habitadas por viejos solitarios, perros callejeros, las fiestas religiosas (único momento con aparente alegría en la Tarde), la depresión, el río, la lluvia.

En todos estos títulos u objetos literarios descritos, se ve ese hilo común del abandono, de la soledad, la violencia y la búsqueda incesante de un motivo de alegría… donde sea que se pueda.

A pesar de ser de Tarde, esta es una sección gris, melancólica. Nunca soleada. Quizás por eso el autor la cierra con un poema dedicado a la lluvia. Ese elemento que limpia, da vida y alegría; es utilizado de un modo tan magistral que, al igual que el agua, el sujeto lírico se va escurriendo por los resquicios y develando aquellas miserias ocultas a simple vista.

Cae la “Noche”, en el Condado.

Para hacer énfasis en la oscuridad, el autor comienza esta tercera sección del libro con un poema dedicado al terrible y habitual “Apagón”. (Hecho tan atemporal como los propios objetos de las casas.)

Y desde este texto comienzan a aparecer, de forma más directa, las personas en el barrio. El cronista describe desde su visión, sus (nuestros) temores, a esos personajes que emergen cuando se oculta el sol: el ladrón, los borrachos, las madres, los llantos de los recién nacidos, los autos, etc.

Pero lo más llamativo de esta última parte son los “homenajes”, los poemas dedicados a personas, vecinos del barrio que son importantes para este autor.

Importantes por diversas razones. En Luisito se ven reflejados esos muchachos que siempre vemos sentados en las aceras, sin estudiar, con ínfulas de maleantes y con el sueño de, algún día, abandonar el país.

Yania es el doloroso recuerdo, la denuncia de aquellos males vigentes en nuestra sociedad: la prostitución y embarazo adolescente. Males sociales que afectan al mundo entero y de los que hay necesidad de hablar; de tomar consciencia.

Ella es el barrio, el legado

su producto interno bruto;

y su hijo será fruto

de otro fruto castrado.

Elianet es una persona muy querida. Cada cubano tiene al menos, una Elianet. Un ser querido que ha dejado esta isla para irse a vivir al extranjero.

Esta crónica es el homenaje que le hace el autor a esta mujer en específico y a todo lo que en ella se ve representado para el lector.

Y cierra de lujo el sujeto lírico este cuaderno, como toda crónica, haciendo un resumen de lo que pudo leerse/verse en esta sección, en el libro. Un resumen de imágenes que nos recuerda a las palabras de Teresita Fernández en su canción “Lo feo”.

Un resumen de esos sentimientos de amor, nostalgia, esperanza, miedos, del sujeto lírico.

Crónicas del barrio es un libro escrito con lenguaje directo, sencillo, pero nunca simple. Con estos poemas, metáforas, analogías y múltiples niveles de lecturas, no puede ser un libro simple. No es una lectura simple. Veleta es un maestro del lenguaje, de la poesía.

Sabe cómo transformar escenas cotidianas en reclamos, denuncias escrita a punta de pluma, pero que viajan como balas cortando la piel más dura, como navajas sevillanas.

“Escribir es un acto de valentía”, se nos ha dicho en muchas ocasiones y este libro lo prueba.

Este es un libro valiente escrito por un hombre valiente que no teme. No teme a regresar a las formas convencionales y a decir lo que siente.

No teme alejarse de los modernismos, de las modas; y viaja, como Carpentier, a la semilla. Utiliza la décima convencional, tradicional. Regresa a esos tópicos y tragedias que han acompañado (y acompañarán) a los seres humanos desde el inicio de los tiempos. Regresa a las formas costumbristas, al romanticismo de antaño… y actualiza todo.

Rompe con todo, utilizando la vieja escuela para crear una nueva. Utiliza los sentimientos del Hombre Nuevo de hoy en día.

El autor no busca que la forma sobrepase al contenido, sino que sea este el protagónico. Jorge Luis Mederos, “Veleta”, busca y consigue que el lector no se pierda ante la parafernalia de los adornos, de la forma rebuscada, del contenido paja.

Veleta ha escarbado, limpiado toda la maleza y deja que el oro brille por sí solo. Utiliza la palabra precisa en cada momento, sin sugerir ni utilizar ambigüedades.

Generalmente en las reseñas o críticas se debe dejar aparte las valoraciones personales, pero en este caso no puedo ni quiero evitarlo.

Es mi deseo dejar la constancia por escrito: Este es un libro, un librazo increíble. Un texto de esos a los que regresaremos los cubanos dentro de 100 años para ver, sentir y revivir cómo era(n) nuestro(s) barrio(s). Una foto de la realidad cubana. Sencillamente: brutal.

Al pan, pan y al vino, vino.

Gracias 😊

Veleta, ¡un maestro de la palabra!

Y de la pesca 🎣

¡Seguro!

👏👏👏