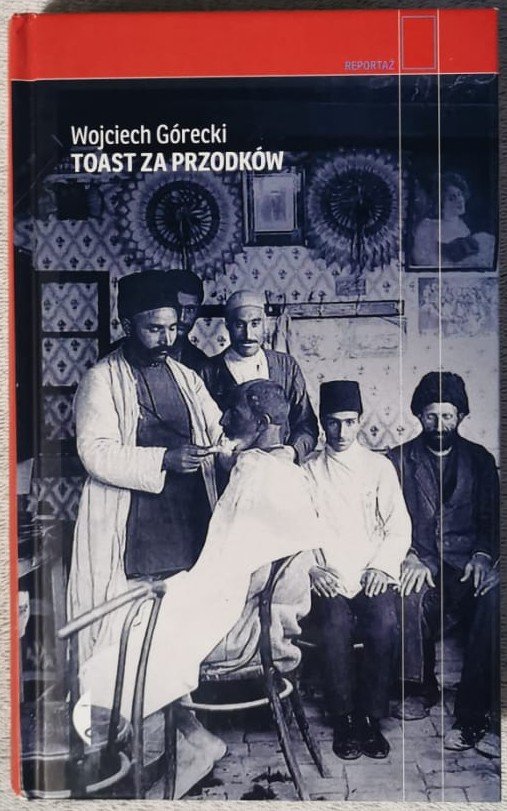

| W podróżach z Wojciechem Góreckim ostatnio zwiedzaliśmy Kaukaz Północny – dziś przyszła kolej na jego południowe zbocza. W książce „Toast za przodków” skupimy się na reportażach z Azerbejdżanu, Gruzji i Armenii. Po części pierwszej kaukaskiej trylogii mamy już mniej więcej jasny obraz tego, na co możemy liczyć i czego możemy się spodziewać i tym razem – wciągających opowieści, spoglądania oczami miejscowych i dużo przyjemności z lektury. Nie rozczarujemy się. |

While travelling with Wojciech Górecki, we recently explored the North Caucasus - today it's our turn to explore its southern slopes. In 'Toast to the Ancestors' we focus on stories from Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia. After the first part of the Caucasus trilogy, we already have a fairly clear idea of what we can expect this time around - exciting stories, seen through the eyes of the locals and a lot of reading pleasure. We will not be disappointed. |

| Układ książki jest zbliżony do tego, który znamy z pierwszej części – najpierw główny rozdział, potem strona lub dwie krótkich, powiązanych tematycznie notatek. Ze względu na swoje doświadczenia życiowe autor zaczyna wędrówkę z nami od Azerbejdżanu, w którym spędził pięć lat, zaś Gruzję i Armenię, które tylko i aż wielokrotnie odwiedzał, umieścił łącznie w części drugiej. Dostajemy 11 rozdziałów z Azerbejdżanu (uzupełnionych 10 odcinkami „Dzienników bakijskich”), 12 z Gruzji i Armenii oraz jeden z Sadachlo. Czemu ten ostatni został wyróżniony, stanie się jasne, gdy do niego dotrzemy. A na razie, podobnie jak przy opisie pierwszej części, przedstawię Wam bardzo zwięźle poszczególne rozdziały. Więc.. w drogę do Azerbejdżanu! |

The layout of the book is similar to that of the first part - first the main chapter, then a page or two of short, thematically related notes. Based on his life experience, the author begins his journey with Azerbaijan, where he spent five years, while Georgia and Armenia, which he visited no less often, are lumped together in the second part. We get 11 chapters from Azerbaijan (supplemented by 10 episodes from the "Baku Diaries’), 12 from Georgia and Armenia, and one from Sadakhlo. Why the latter was highlighted will become clear when we get to it. But for now, as with the description of the first part, I will give you a very brief introduction to each chapter. So... let's go to Azerbaijan! |

| - „Punkt widzenia” – rozdział króciutki, niespełna jedna stronica. O wrażeniach jednego ze znajomych autora, odwiedzających go w Baku. Gdy przybył tam z Teheranu – rzekł „Czuję się jak w Europie”. Gdy potem przybył z Warszawy – „To jednak Azja”. Za trzecim razem już nic go nie dziwiło. |

- 'Point of view' - a very short chapter, less than a page. About the impressions of a friend of the author who visited him in Baku. When he arrived there from Tehran - he said: "I feel like in Europe". Later, when he arrived from Warsaw - "This is Asia". By the third time, nothing surprised him. |

| - „Lekcja geografii” – z wizytą w domu przesiedleńców z Karabachu. Choć od czasu, gdy musieli opuścić swoje domy, minęło już kilkanaście lat, ich życie w nowym miejscu wciąż jest tylko prowizorką. Dwóch braci o kompletnie różnych charakterach: jeden – człowiek Zachodu, drugi – członek świata Orientu. Plus przypowieści i obszerny cytat z „Alego i Nino”, w którym rosyjski carski nauczyciel próbuje przekonać dzieci, że to od nich będzie zależeć, czy ich miasto „będzie należeć do postępowej Europy, czy do zacofanej Azji”. Po czym jeden z uczniów odpowiada: „Przepraszam, panie profesorze, ale my byśmy chcieli zostać w Azji.” |

- 'Geography lesson' - a visit to the home of displaced persons from Karabakh. Although more than a dozen years have passed since they were forced to leave their homes, their life in the new place is still a makeshift one. Two brothers with completely different characters: one a westerner, the other a member of the oriental world. There are also parables and an extended quotation from "Ali and Nino", in which a Russian tsarist teacher tries to convince the children that it will be up to them to decide whether their city "will belong to progressive Europe or backward Asia". To which one of the pupils replies: "Excuse me, Professor, but we would like to stay in Asia." |

| - „Wnuczka imama” – historia młodej Gülnary, wnuczki imama z rodu potomków Proroka, która podczas studiów w Paryżu poznaje pewnego Francuza. Dziewczyna staje przed życiowym wyborem – uczucie, czy uwarunkowanie i poczucie obowiązku wobec klanu? |

- 'The Imam's Granddaughter' - the story of young Gülnara, granddaughter of an imam from a family of descendants of the Prophet. While studying in Paris, she meets a Frenchman and is faced with a life choice - affection or conditioning and a sense of duty to the clan? |

| - „Palimpsest” – o narodzie Udinów, potomków Albanii Kaukaskiej i próbie odbudowy ich tradycji, kultury, wiary – chrześcijańskiej, ale o nieznanym obrządku, w której główną rolę odegrał jeden, pojedynczy człowiek. I, jak można się domyślić, nie został za to odpowiednio doceniony. |

- 'Palimpsest' - about the Udin people, descendants of Caucasian Albania, and the attempt to rebuild their traditions, their culture, their faith - Christian, but with an unknown rite in which one man played a major role. And, as you might guess, he was not properly recognised for it. |

| - „Wódz” – o długoletnim przywódcy Azerbejdżanu, Heydərze Əliyevie. O tym, jak dochodził do stanowisk za czasów radzieckich, o zwycięskiej walce o władzę z Əbülfəzem Elçibəyem i o tym, jak doprowadził do przekazania władzy swojemu synowi İlhamowi. Demokracja? Są skuteczniejsze metody. A czy krajowi wyszło to na dobre, to już historia osądzi i to raczej nieprędko. |

- 'The Chief' - about the long-time leader of Azerbaijan, Heydər Əliyev. How he rose to power during the Soviet era, his victorious struggle for power with Əbülfəz Elçibəy, and how he managed to transfer power to his son, İlham. Democracy? There are more effective ways. The history will judge whether it has worked out well for the country, but probably not soon. |

| - „Solidny” – o kaście „solidnych”, mogących znacznie więcej, niż przeciętny obywatel – czasami zgodnie z prawem, ale najczęściej naginających je plastycznie do własnych potrzeb. Sportretowanej przez historię o wynajmie mieszkania w prestiżowej okolicy. |

- 'The Reliable One' - about a caste of ‘Reliables’ who can do much more than the average citizen - sometimes in accordance with the law, but most often by cleverly bending it to suit their own needs. Portrayed through a story about renting an apartment in a prestigious neighbourhood. |

| - „Mamed” – o prawniku, który postanowił pomagać biednym, udzielając bezpłatnych porad i jak to się skończyło w państwie przesiąkniętym korupcją. | - 'Mamed' - about a lawyer who decided to help the poor by giving free legal advice, and how this ended up in a corruption-ridden state. |

| - „Pir” – historia pewnego ludowego świętego wielu imion, do którego ludzie pragnący pozbyć się choroby podróżowali zarówno za jego życia, jak też i po śmierci, staje się pretekstem do opowieści o „pirach” – świętych, leczniczych miejscach, w których islam „oficjalny” ustępuje „ludowemu”. | - 'Pir' - the story of a folk saint of many names to whom people travelled to get rid of illness, both during his lifetime and after his death, becomes the pretext for the story of ‘pirs’ - holy, healing places where ‘official’ Islam gives way to ‘folk’ Islam. |

| - „Iczeri Szeher” – o najbardziej wewnętrznej i najstarszej części Baku, wokół której w okresie naftowej gorączki z końca XIX wieku wyrosło miasto nowe, wielokulturowe, ośrodek kultury, inteligencji, najbardziej „zachodni” fragment Azerbejdżanu. O trudnych relacjach między Azerami i Ormianami. O tym, jak się to wszystko załamało, gdy zamiast Ormian, Żydów, Rosjan napłynęły masy ludzi z prowincji. I w jakim kierunku się zmieniło, gdy ponownie pojawiły się petrodolary. |

- 'İçəri şəhər' - about the innermost and oldest part of Baku, around which a new, multicultural city, a centre of culture, intelligence, the most ‘western’ part of Azerbaijan, grew up during the oil fever of the late 19th century. About the difficult relations between Azeris and Armenians. About how everything broke down when masses of people from the provinces came to replace the Armenians, Jews and Russians. And how things changed when the petrodollars returned. |

| - „Hinalug. Koniec historii” – powrót do Xınalıqu, w nowych realiach. Niegdyś koniec świata, gdzie lokalna społeczność mogła funkcjonować tak, jak przed wiekami, kultywując własny język i tradycje. Gdy pod koniec lat 60 wybudowano pierwszą drogę do wsi, oznaczało to początek końca. Zwyczaje zaczęły zanikać, tradycyjną kulturę zaczęła wypierać masowa, obca, pojawiła się wódka… I pieniądze turystów, które zabiły tradycyjną gościnność. Mimo to autor odnajduje jeszcze resztki dawnej magii i zwraca uwagę na sąsiednie wsi, zamieszkane przez inne małe narody – w których zaraza globalizacji jeszcze się nie rozpanoszyła i gdzie gość (bo turyści tam nie docierają) wciąż ma szansę odnaleźć ten region takim, jakim był przed wielu laty. Plus ciekawa historia o dumnym i mądrym pastuchu, którego wieś wysłała do pobliskiego miasta, by ją reprezentował podczas procesu złoczyńców nękających cały region. |

- 'Xınalıq. The End of History' - a return to Xınalıq, in new realities. Once the back of the beyond, where the local community could function as it did centuries ago, cultivating its own language and traditions. When the first road to the village was built in the late 1960s, it was the beginning of the end. Customs began to disappear, traditional culture was replaced by mass, foreign culture, vodka arrived... And tourist money, which killed the traditional hospitality. Nevertheless, the author still finds remnants of the old magic and draws attention to neighbouring villages inhabited by other small nations - where the plague of globalisation has not yet spread and the guest (because tourists don't come there) still has a chance to find the region as it was many years ago. There is also an interesting story about a proud and wise shepherd, whom the village sent to a nearby town to represent them during the trial of the villains who were plaguing the entire region. |

| - „Ketman” – pojęcie charakterystyczne dla szyitów, pozwalające im przetrwać we wrogim otoczeniu i jego wpływ na życie Azerbejdżan, na historię kraju i na trudne wybory życiowe, wbrew własnym poglądom. Tłumaczy między innymi, dlaczego – choć wcale nie tak mało ludzi jest przeciwnych władzom, to i tak wciąż na nie głosują. |

- 'Kitman' - a Shiite concept that allows them to survive in a hostile environment, and its impact on Azerbaijani life, the country's history and the difficult choices in life despite one's views. It explains, among other things, why - although not so few people are against the authorities - they still vote for them. |

| Czy powyższe pół książki pozwala stać się ekspertem od Azerbejdżanu? Zdecydowanie nie. Ale czy daje nam możliwość poznania go choć trochę lepiej, i to również w aspektach, o których na co dzień nie pisze się w gazetach, nie mówi w telewizji? Zdecydowanie tak. Gdy mamy to już za sobą, pora wyruszyć w dalszą podróż po Zakaukaziu. Kolejne rozdziały prowadzą nas przez kolejne kraje. |

Does the first half of the book make you an expert on Azerbaijan? Definitely not. But does it give us the opportunity to get to know the country at least a little better, including the aspects that aren't written about in the newspapers or talked about on television every day? Definitely yes. Now that we've got that out of the way, it's time to continue our journey through Transcaucasia. The following chapters will take us through further countries. |

| - „Na granicy” – krótki rozdział, w którym spoglądamy na Kaukaz i Zachód oczami Pasztuna Alego rodem spod Peszawaru. | - 'On the Border' - a short chapter in which we look at the Caucasus and the West through the eyes of Peshawar-born Pashtun Ali. |

| - „Przedmurze” – o miejscu Gruzji i Armenii w świecie, postrzeganym przez ich mieszkańców. O historii Gruzji – krótko, ale treściwie, od starożytnych Kolchidy i Iberii, przez złoty wiek Dawida IV i Tamary, wchłonięcie przez carską Rosję, czasy radzieckie, okres wojny domowej, aż po współczesność. |

- 'The Foreground' - about Georgia and Armenia's place in the world as perceived by their inhabitants. The history of Georgia - brief but informative, from ancient Colchis and Iberia, through the golden age of David IV and Tamar, incorporation into Tsarist Russia, the Soviet era, the period of civil war, to the present day. |

| - „Ikona” – o Stalinie, o tym, jak rozmaicie bywa postrzegany w Gruzji – od tyrana i zbrodniarza, po uwielbianego przywódcę. O muzeum w Gori. I o ikonie, która do dziś przetrwała w niedalekim Ateni, pod opieką pani, prowadzącej małe, prywatne muzeum. |

- 'Icon' - about Stalin and how he is perceived in various ways in Georgia - from a tyrant and criminal to a glorified leader. About the museum in Gori. And about an icon that still survives in nearby Ateni, in the care of a lady who runs a small private museum. |

| - „Stół” – o gruzińskiej biesiadzie i o toastach. Po prostu. | - 'The Table' - about Georgian feasting and toasting. Just that. |

| - „Złote runo” – podróż w czasie i przestrzeni przez różne regiony Gruzji. Megrelia tuż po wojnie domowej i nocleg na posterunku policji pod Zugdidi. Kachetia i listopadowa biesiada w Lagodechi. Adżaria i poszukiwanie starych drewnianych meczetów w okolicy Chulo. Guria – bardzo krótkim przejazdem – i Imeretia z knajpką w Zestaponi. Kartlia – Wewnętrzna i Dolna, w tej ostatniej obchody Giorgoby w Dmanisi. No i Swanetia, dzika, górska… mająca swoich Janosików i swoich mistrzów wspinaczki. A także legenda o twierdzy suramskiej. |

- 'The Golden Fleece' - a journey in time and space through different regions of Georgia. Megrelia just after the civil war and a night in a police station near Zugdidi. Kakheti and the November feast in Lagodechi. Adjaria and the search for old wooden mosques near Khulo. Guria - a very short drive - and Imeretia with a tavern in Zestaponi. Kartlia - Inner and Lower, the latter a celebration of Giorgoba in Dmanisi. And then there's Svaneti, wild, mountainous... with its Robin Hoods and its climbing masters. And the legend of the Surami fortress. |

| - „Tbilisoba” – trudno, żeby nie było oddzielnego rozdziału o Tbilisi, stolicy, w której mieszka około 1/3 mieszkańców kraju. Współczesność i historia. Stare Miasto i aleja Rustawelego. I boczne podwórka. |

- 'Tbilisoba' - it's hard not to have a separate chapter on Tbilisi, the capital where about a third of the country's population lives. Modernity and history. The old town and Rustaveli Avenue. And the backyards. |

| W tym momencie przechodzimy do części armeńskiej: | At this point we move on to the Armenian section: |

| - „Arka” – tytuł mówi jasno, że będzie tu o górze Ararat i jej wielkim znaczeniu dla Ormian i ich kultury. Zarys historii Armenii, dzieje klasztoru Chor Wirap, do tego Mesrop Masztoc i jego alfabet. |

- 'The Ark' - the title makes it clear that this is about Mount Ararat and its great significance for the Armenians and their culture. An outline of Armenian history, the history of the Khor Virap Monastery, plus Mesrop Mashtots and his alphabet. |

| - „Rabis” – tytułowy rabis to pewien rodzaj muzyki, łączący Wschód z Zachodem… Sam rozdział opowiada o historii ormiańskiej diaspory, rozproszonej po całym świecie – od Polski po Liban, od Iranu po Stany Zjednoczone. I o jej wpływie na obecną politykę. |

- 'Rabis' - the rabis mentioned in the title is a certain kind of music that connects East and West... The chapter itself tells about the history of the Armenian diaspora scattered all over the world - from Poland to Lebanon, from Iran to the United States. And its influence on contemporary politics. |

| - „Chaczkary” – o ormiańskim Kościele, jego świętych miejscach, o życiu klasztornym. I o chaczkarach jako jednym z symboli ormiańskiej wiary. |

- 'Khachkars' - about the Armenian Church, its holy places, monastic life. And about the khachkars as one of the symbols of the Armenian faith. |

| - „Sjunik” – o granicy z Iranem. O tym, dlaczego czasami najłatwiej się stamtąd wyrwać, gdy w rolę taksówkarza wciela się celnik i jak taka podróż może się skończyć gościną. No i o tym, jak bardzo różni się wschodnie pojęcie czasu, od zachodniego. |

- 'Syunik' - about the border with Iran. On why sometimes the easiest and quickest way out is when a customs officer plays the role of a taxi driver, and how such a journey can end in becoming a guest. And about how the Eastern concept of time differs from the Western. |

| - „Tuf” – o Erywaniu i jego historii, o tym, jak zmienił się z malutkiego miasteczka w lokalną metropolię, w dużej mierze właśnie dzięki tytułowemu tufowi, z którego wybudowano większość nowych domów w tamtej epoce. | - 'Tuff' - about Yerevan and its history, and how it changed from a small town to a local metropolis, thanks in large part to the titular tuff, from which most of the new houses of the time were built. |

| - „Poeta” – o Harutjunie Sajadjanie, znanym bardziej jako Sajat-Nowa, przynależnym do każdego z południowokaukaskich narodów – Ormianinie, który spędził większość życia w Gruzji, a tworzył, najczęściej, po azerbejdżańsku (choć także po ormiańsku, po gruzińsku, a nawet po persku). | - 'The Poet' - about Harutyun Sayadyan, better known as Sayat-Nova, who belonged to each of the South Caucasus nations - an Armenian who spent most of his life in Georgia and wrote mostly in Azerbaijani (but also in Armenian, Georgian and even Persian). |

| I wreszcie na koniec – „Sadachlo”. Tytułowa wieś leży w Gruzji, tuż przy granicach z Azerbejdżanem i Armenią, tworząc, siłą rzecz, miejsce, w którym te trzy narody od wieków żyją wspólnie i muszą mieć opanowaną niełatwą sztukę koegzystencji. Od czasów późnoradzieckich do objęcia rządów przez Saakaszwilego kwitł tam handel, największe targowisko na Kaukazie osiągające obroty rzędu miliarda dolarów rocznie. Na tym tle autor opowiada o relacjach poszczególnych narodów, ich wrogości i/lub wzajemnej sympatii, o konfliktach, które nękały ten region w przeszłości, które – prawdopodobnie – niestety będą go nękać i w przyszłości, i o tym, jak w tym wszystkim odnajdują się zwykli ludzie. |

And last but not least, 'Sadakhlo’. The village of the title is in Georgia, right on the border with Azerbaijan and Armenia, a place where the three nations have lived together for centuries and must have mastered the uneasy art of coexistence. From late Soviet times until Saakashvili took power, trade flourished there, the largest market in the Caucasus reaching a turnover of one billion dollars a year. Against this backdrop, the author tells the story of the relations between the various nations, their enmity and/or mutual sympathy, the conflicts that have plagued the region in the past and - unfortunately - will continue to do so in the future, and how ordinary people find themselves in the middle of it all. |

| Podobnie, jak w przypadku poprzedniej książki, lektura dostarcza wiele cennej wiedzy, takiej, którą niełatwo zdobyć z innych źródeł. Autor po prostu pisze o tym, czego sam doświadczył, dzieli się swoim doświadczeniem i swoimi spostrzeżeniami. Moje własne – przynajmniej w kwestii Gruzji i Armenii – choć znacznie skromniejsze, są zbliżone, a to, co sam przeżyłem, jest spójne i zbieżne z tym, co przeczytałem. Do Azerbejdżanu jeszcze nie dotarłem. Ale nie spodziewam się, by czekało tam na mnie coś diametralnie różnego od tego, co poznałem dzięki tej książce, a to znaczy, że również tam będę się czuł swojsko. Może nawet, dzięki niej – jeszcze bardziej swojsko. |

As with the previous book, there is a great deal of valuable knowledge to be gained from reading this book, the kind of knowledge that is not readily available from other sources. The author is simply writing about what he has experienced, sharing his experiences and insights. My own - at least as far as Georgia and Armenia are concerned - although much more limited, are similar, and what I have experienced is consistent and convergent with what I have read. I have not yet reached Azerbaijan. But I don't expect to find anything diametrically opposed to what I've read in this book, and that means I'll feel at home there too. Perhaps, thanks to it, even more at home. |

| Z tego względu również i „Toastowi za przodków” daję ocenę maksymalną. | For this reason, I give ‘Toast to the Ancestors’ the maximum rating. |