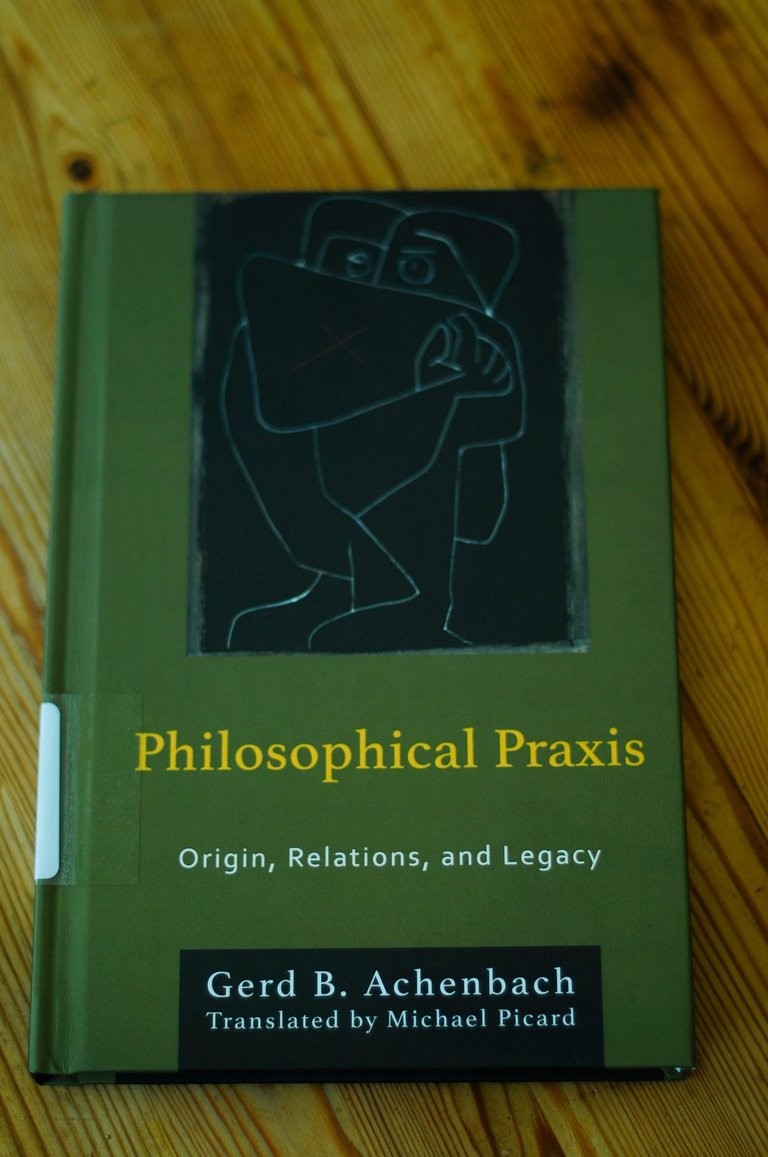

For the last couple of years, almost ten to be somewhat specific in still a vague sense, I have been doing research on the “newish” field of practical philosophy Philosophical Counselling (PC). Hence the reason for calling this fermented review a bit biased. There are two reasons for this, firstly, because it is the field of research that I am interested in, and secondly, because I have wished and waited for this book for so long. The book, Philosophical Praxis: Origin, Relations, and Legacy by author Gerd Achenbach, has been in rumour for a couple of years now. The book is the long awaited first English translation of Achenbach’s seminal work from the 1980s. Forty years after the initial work was published in German, Philosophische Praxis, the English translation saw the light of day. And I got my hands on a copy, I read through it, and I was surely not disappointed! But as noted, this review will be a bit biased, because I have waited for it for so long…

Without further ado.

What is philosophical counselling, PC, philosophical practice/praxis? This is one of the central questions the book deals with. But rather than define the practice, circumscribing its boundaries, Achenbach turns the problem on its head and in some sense frustrates and thwarts our expectation to find out what exactly this field is. We are not given any definite description, we are not given definitions or even attempts at telling is in the broadest sense of the word what this field even is. Instead, we are given passages that read something along the lines of:

“The ambition of … philosophy was not to provide a foundation to praxis, but to explore it,” (p.9).

“Put bluntly: there is no place … that Philosophical Praxis can find its bed ready made,” (p11).

These types of statements are found throughout the book, and one is left with more questions than answers. And this is the point of the book, to not give you any guidelines, directions, or any ideas which can begin to box the practice in. We are merely told that philosophical counselling is much like fluid taking the shape of the container. The idea behind Achenbach’s praxis is that each individual demands a unique experience, and I do not mean the the visitor demands it herself; instead, her presence demands that the philosophical counsellor treat her not as a symptom or a case, but as an individual that profoundly challenges the philosophical counsellor.

When I read the book, I was constantly reminded of the quote by psychotherapist Sheldon Kopp, who notes beautifully that the psychotherapist is not there to guide the lost souls out of the forest. That is, the psychotherapist does not and cannot provide the visitor a map that they can then use to get out of the forest; instead, the psychotherapist can merely guide the lost visitor on the pathways that does not lead out of the forest. This stems from the psychotherapist being lost for so much longer than the visitor, so the psychotherapist can guide the visitor on which paths will only lead deeper into the forest. Kopp concludes the story or metaphor rather beautifully with the following:

The words of the psychotherapist and the philosophical counsellor, if we follow Kopp and Achenbach, cannot lead the visitor out of their problem, there is not dogmatic way that the visitor can navigate their way through the thicket into the clearing. The philosopher in this image can only tell the reader the ways they know will not work, so that the visitor might not get even more lost. And this is the key insight from Achenbach: The philosophical counsellor can merely act as a guide on this strange journey we call life; collaboratively discussing things that the visitor might want to discuss.

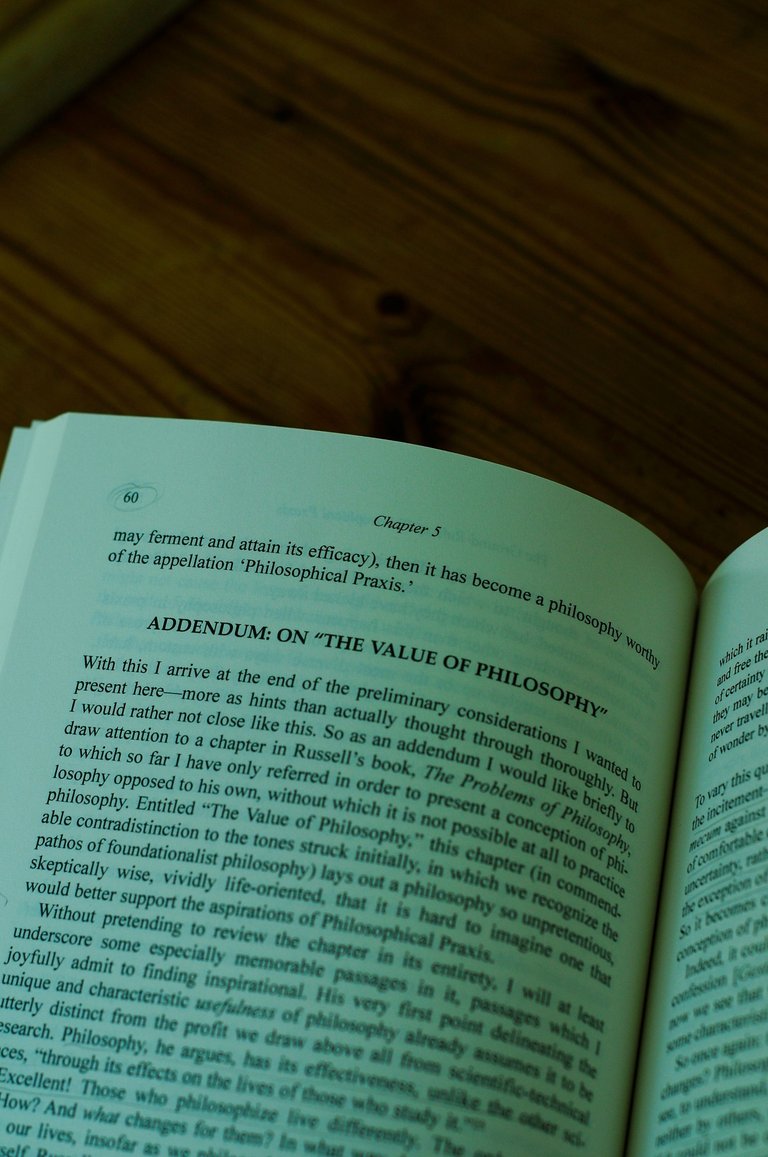

Achenbach’s book consists of twelve very easily digestible chapters (if you are somewhat familiar with philosophy and philosophical counselling). There are some chapters on education (Chapter 8), what philosophical praxis is – but don’t be fooled by this title (Chapter 1), the history of philosophical practice (Chapter 2), and how philosophical praxis differs from psychotherapy and pastoral care (Chapter 12). These chapters, even though if I wrote the book, I would have radically placed them in different orders, nicely set out in a very vague and philosophical way what the practice is. I say vague because as mentioned above Achenbach does not want to give anything away, he does not want to give us any guidelines, definition, and so on, because he feels like this is a disservice to what philosophy is.

But then there are also other interesting chapters through which he writes and creates new concepts in German, which is rather problematic and difficult to translate into English (for obvious reasons). This reminds one a bit of Martin Heidegger, for those well versed in philosophical history, regarding the creation of words unique in German which cannot be translated into English. In, for example, chapter 3, we are introduced to one such construction, which Achenbach calls Lebenskönnerschaft, and which the translator did not and could not translate into English. This idea of Achenbach is similar to the notion of phronesis, also a problematic idea and terms to translate into English. One might very badly and in an oversimplified manner state that this idea relates to life skills that one develops throughout one’s life, but in a specific way, aligned with the Socratic idea of examining one’s life. I would need an entire chapter to translate this idea in more detail though, so this will have to do!

In the other chapters, more practical issues are dealt with, for example, the virtues of the philosophical counsellor and philosophical praxis (Chapter 9), and in chapter 6 Achenbach discusses the various “beginnings” of philosophical counselling sessions. Here, he provides some explicit and hands-on examples of how he would have handles cases in his practice.

One interesting thing that is provided in this work is “case studies”. Most of his contemporaries, various philosophical counsellors, provide ample “case studies” of past clients they dealt with. I find these “case studies” problematic for various reasons, but this is not the place to discuss this. Achenbach provides various hypothetical cases, and I think this works incredibly well in contrast to discussing “real” cases with “real” people. This allows us as the reader to add our own interpretations, it provides Achenbach with much more space to discuss cases for us, and it again reinforces the idea that there is no single and one way of approaching the visitor’s questions and problems.

After reading the book, I felt inspired to dive back into the studies, back into what inspired me in the first place to take a look at this new field. The book is a must have for anyone interested in this field, along with Hadot’s Philosophy as a way of life. I think that the future for philosophy outside of academia and the dusty halls of old professors is looking bright. Especially in South Africa (of all places), there is incredible renewed interest in this field, with so much potential to those who want to enter the new space.

As noted, this review is a bit biased, and I also want to write an official book review for a local academic peer-review journal in the coming weeks. But it was a fun read, and if you read the whole book review, I hope that I inspired in you the excitement to pick a copy! It is quite expensive, because it is published through an academic publisher, but if you can find a copy, do buy it.

For now, happy reading, and keep well.

All of the musings are my own, albeit inspired by the words and praxis of Achenbach. The photographs are also my own, taken with my Nikon D300.

The Fermented Philosopher's Library

| 🕮 The Book of Malachi | 🕮 The Outsider | 🕮 A Clockwork Orange | 🕮 Perfume |

|---|---|---|---|

| by T.C. Farren | by Stephen King | by Anthony Burgess | by Patrick Suskind |

| 🕮 The Uninvited | 🕮 Life Is Elsewhere | 🕮 Philosophy as a Way of Life | 🕮 The Space Between the Space Between |

|---|---|---|---|

| by Geling Yan | by Milan Kundera | by Pierre Hadot | by John Hunt |

| 🕮 Ezumezu: A System of Logic for African Philosophy | 🕮 Adjustment Day |

|---|---|

| by Jonathan O. Chimakonam | by Chuck Palahniuk |