"What you don't offer - especially in volatile times - people will make up for themselves." (Anna Burns, 'Milkman')

Sometimes, I think if I was left to read nothing but Irish literature for the rest of my life, I could be quite happy. It carries in it a sharp contrast between the bitterness of life and the grab-it-with-both-hands quality of the writing. There's a great, almost suffocation oppression, peppered by bursts of acute living.

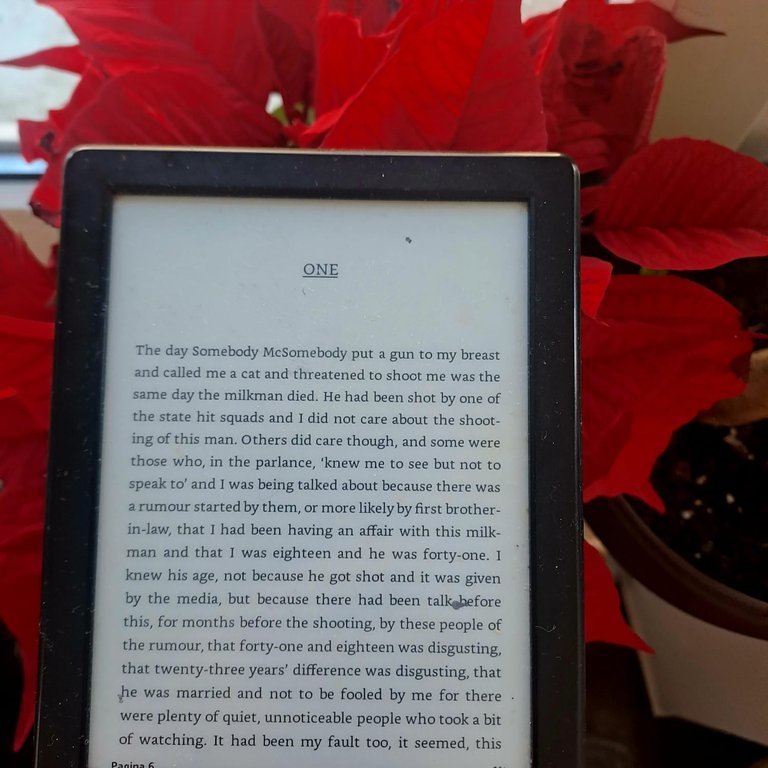

So it is that much of my focus of late has been contemporary Irish writers, with two recent reads sticking out in particular, as they seem to go hand-in-hand. Anna Burns' Milkman tells the story of an 18-year-old unnamed girl who becomes the target of a dodgy (also unnamed) character, known only as "the Milkman". The Milkman is a middle-aged paramilitary officer who behaves suggestively (and quite threateningly) toward the protagonist, much to the girl's dismay. Yet not only is she helpless before him, she soon becomes the object of public scorn and gossip as word spreads of their alleged affair.

A heavy sense of oppression drips from the page, as Burns examines how the girl's reputation (and life) is destroyed by this imagined affair. It's a heavily political novel, returning us to the author's childhood during the 1970s, against the backdrop of the Troubles. On a more personal level, it's an exploration of how toxic closed societies can be. By the end of the novel, it hardly seems to matter whether or not the girl is in fact screwing the Milkman. The damage has been done.

"Being loved by the person he loved to the point where he couldn't cope anymore with the vulnerable reciprocity of giving and receiving, he ended the relationship to get it over with before he lost it, before it was snatched from him, either by fate or by somebody else." (Anna Burns, 'Milkman')

The other book that's on my mind was Louise Kennedy's Trespasses. Also set during the Troubles, the book follows 24-year-old Cushla who lives with her alcoholic mother and who becomes infatuated with Michael, a Protestant barrister twice her age, after a chance encounter. Soon enough, Cushla becomes the "other woman" (stereotypical at times, but you can't help feeling for her) in Michael's life, and though political differences and jealousy keep them in a perpetual to-and-fro, they just can't seem to let go of one another.

On the surface, it seems to contrast Milkman in that here, the young female protagonist does begin an affair with this older, married man (both men controversial figures in times of political and social chaos). But really, it's just a difference of nuance.

"Here were females who did love the sound of breaking glass." (Anna Burns, 'Milkman')

In their hearts, both books are these precious, curious looks at the complex relationship between love and violence. I love the way both authors capture the violence, and with both, I was surprised to discover that the authors are in their 50s/60s (I would've expected much younger women, perhaps because of the sentimental and day-to-day angsts of the characters), but it makes sense. It's clear these women knew this violence personally, slept with it under their pillow as children.

A sense of helplessness pervades both books. The authors seldom resort to overt, graphic descriptions of the violence (making those descriptions all the more powerful). And I think that's precisely the point. After all, with an isolated attack, you can well go into details and specifics, but they will be dampened in the end by the isolated nature of the event. But here, we're talking about such a vast stretch of terror, entire lifetimes where violence was simply the norm, hardly worth minding at all, and for that, you can't maintain this prolonged overt gore. Both Burns and Kennedy pack morsels of insidiousness in their writing, so that the fear and aggression latch onto the reader long after the book is finished. And somehow, the broader political unease, the endless danger and violence the girls live in, flow superbly into the more universal, more mundane matters of love and lust.

It's not for nothing that we say all's fair in love and war, because both are brutal, visceral and will have an impact on the larger circle/community, regardless if you participate or not.

In both books, the older men's lust, this becoming the object of desire reads almost like an attack for the girls. An overwhelming lunge towards them that neither protagonist is strong enough, or perhaps old enough, to withstand or get out of the way of. You could argue that Burns's protagonist, the brilliantly-named "middle sister", is more in the right here as she doesn't actually indulge the older man's fantasies. But really, I think the larger point of the books is that it does not matter.

There's a certain air of damned if you do, damned if you don't. You genuinely feel for both girls, both doing everything they can at home and in their social/personal life, and yet it matters so little, in the end. Burns accentuates this as the girl tries, time and again, to clear her name with her town, yet her words fall on deaf ears - her own mother, even, believes the town gossip over her daughter's word.

"He laughed, a sound she felt in her lungs, and she thought she would do anything to make him happy." (Louise Kennedy, 'Trespasses')

In Kennedy's Trespasses, there's the intimation that involving yourself can have dire consequences, both to yourself and to those around you. But read in contrast with Burns's Milkman, it seems like staying out of things doesn't lead to better outcomes. Thinking back on it, I think that was my favorite part about both books - that they weren't morality lessons. At no point did I feel the middle sister was somehow superior for keeping clean, nor that Cushla was implicitly lowly or foul by sleeping with a married man. There's a muddiness to both books, a sense of being close to the earth, the life-source, where it becomes hard to remember which way is up and what is the right answer to live your life by.

To an extent, I'm sorry I read them, the way one always is with really good writing - because I'll never get to discover them for the first time again. But you could, which is why I've tried to keep this free of spoilers. :)

Excellent review, my dear! You clearly resonated with the themes or at least felt that joy of pulling at a thematic thread to see what you could reknit from it.

Irish literature, hmm. Not to say I haven't enjoyed an Irish writer or two but I tend to avoid them. However, on your recommendation I'll see if they are in my library.

Congratulations @honeydue! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCheck out our last posts:

What are the chances that after I stumbled upon some Irish history of my own, I come across your review.

This was lovely to read, not so much in terms of the situations 😅 but the way that these books spoke to you. Some people don't enjoy exposing themselves to the more sensitive topics in life, but I think we need them in order gain a broader perspective of people, and life...

Thank you for sharing this 🙏 I hope to read more Irish literature as well, especially the epics

You certainly did a good job of piquing my curiosity! Now I might just have to read one of these...or both.

Maybe when time goes by and you go back to them, you discover hidden things... it always happens because we grow up and change a lot of things in our way of thinking and seeing life. So no doubt this could be fresh air, like that first time feeling.

Thanks for the recommendations. 😉

thanks for the spoiler free review and that is very hard to do as a book review.