Good day Hivers and Book Clubbers,

I finally pick up the virtual pen again to talk about books. I see that the last review I did here was in August, so almost 5 months ago. I did do a lot of reading in the meantime, so I've built up quite the reserve of books to talk about on this platform. Not that I feel like talking about all of them.

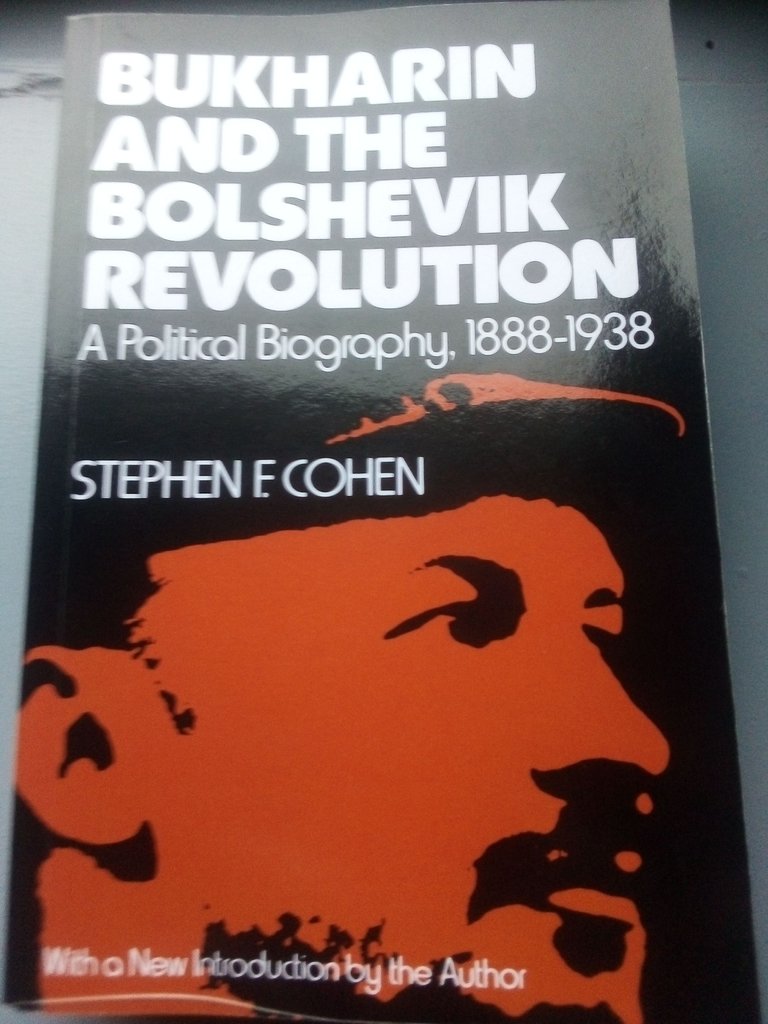

The book I've picked for today is titled 'Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution; a political biography 1888-1938', written by Stephen F. Cohen. Originally written in 1973, I picked up my 1980 copy from Amazon, so I suppose it's quite widely available still. The story proper, excluding references, notes etc. amounts to almost 400 pages, so it's a decently sized read.

The forgotten Bolshevik

Few events in world history are as well-known as the Russian Revolution, and for good reason. The Romanov Czars had ruled Russia for over 3 centuries, so their overthrow would be a big event. That this happened by the Bolsheviks, a manifestation of revolutionary socialism, made the event even more remarkable. The adventure lasted for just over 70 years, so quite a bit shorter than the czars did.

But Cohen doesn't talk about the end of communism in the book; that had not happened yet when he wrote it. The book focuses a lot more on the years from the Revolution in 1917 up to the 1930s.

Many people know the big players at least by name: most would recognize Lenin, Stalin and probably Trotsky as well. But who knows Nikolai Bukharin?

His role in the Bolshevik party was significant, his influence on Russian policy was dominant in the 1920s. And yet, his name has not stood the test of time as well. There are multiple reasons for this.

Evolution or Revolution?

Socialism as an ideology can be subdivided in many ways, as is the case with most ideologies. One of the main splits is between the ideas of Evolution and Revolution. Should the socialists take power through the existing systems, for example by participating in elections? Or should its aim be to overthrow the system through insurrection and revolution?

This is not only a discussion for how to take power, but also for how to act once power has been gained. Does the revolution continue by upsetting all old systems, or should socialist progress be more gradual?

The Bolsheviks took power through revolution in 1917, there is no other way to read the events of that year. But once they were in power in Russia the picture became more blurred. During the civil war with the Whites (a varied and loose group consisting of Czarists, right-wing and liberals, among others), there was internal revolution as well, dubbed as War Communism. Requisitioning of goods, forced nationalisations of factories were the order of the day.

But this slowed down once the civil war was won. Bukharin came down hard on the side of Evolution for the internal development of socialism in Russia. What this meant in practice was that private property would continue to exist, especially in the countryside. The planned economy would not figure into his plans, nor would forced collectivizing of farms.

Smychka

Bukharin was very absorbed with the rural questions that arose in Russia. The peasants' position under Czarism was troubled; while serfdom was abolished in the 1860s, their lot had not improved much. There was a shortage of land, in Russia of all places, due to peasants not being able to move, and the massive estates of the nobility did not help.

So, the peasants took action themselves in 1917. While the Czarist order collapsed in St. Petersburg and Moscow due to revolution, the peasants marched onto the noble estates and started dividing the lands amongst themselves. This was applauded by most socialist as a case of fair redistribution, but the private ownership of land was contrary to communist theory.

The question of the 'kulaks', as the more wealthy of the peasants came to be known, would trouble the Bolsheviks for decades. And are the peasants a class of their own? Communist rhetoric was very familiar with the city-dwelling industrial proletariat, but this class was almost absent in overwhelmingly rural Russia. So Bukharin theorized a bond of friendship and understanding between the city-dwellers and the peasants, which was termed as 'smychka'.

Bukharin would let the peasants stay as private smallholders, in contradiction to communist theory and later practice. His economic ideas were dubbed the 'New Economic Policy', or NEP for short. They would be Soviet practice during the 1920s. Lenin was in favour of this gradualist, evolutionary road towards socialism. After Lenin's death, Bukharin would be one of the biggest and most influential men in the Soviet Union. But the other man of this stature would eliminate him in due time.

What goes up, Stalin puts down

Joseph Stalin was a relatively late addition to the Soviet story. His appointment as Secretary of the party gave immense power to a man with Machiavellian political abilities. And Stalin was just that man. During the 1920s, he would eliminate his opponents one by one, and appoint his own men in influential positions.

Bukharin, who was a member of the Politburo and the editor of Pravda, the main Soviet newspaper, was a prime target from the beginning, also because of his ideological differences with Stalin. His group would become known as the Right Opposition, though we wouldn't recognize his positions as right-wing at all.

Stalin was an opponent of NEP policies. His view of the economy was simple; a planned economy would kickstart the Industrial Revolution in Russia. And the private farms would be collectivized, with the Kulaks destroyed as a group.

He would put these ideas into practice from 1929 onwards, when his position in the Bolshevik party was solidified. Bukharin, while in the opposition, was also in the minority in the party. Yet he remained a thorn in the side of Stalin. Bukharin was well-liked, more intellectually inclined, but was less of a political operater, which would literally mean his death.

He ended up receiving the death-penalty in a show-trial, which would lead to his execution in 1938. The details of his death remain unknown.

Conclusion

The death of Bukharin would not mean the death of his ideas. Soviet Russia would creep towards his view of economics and society again after the death of Stalin. His name became somewhat rehabilitated in the 1960s and 1970s, though his fame today is less than the other big names from Soviet Russia.

This book is worth picking up for those interested in either political ideas, specifically communism, and Russian history in general. It's hard to do justice to a 400 page book in not too many words with an abundance of ideas and insights. As said before, I bought this off of Amazon, so I think it's quite widely available.

Consider it my New Years resolution to do more writing again. I'll see you all in the next one,

-Pieter Nijmeijer

(Top image; self-made photo of book cover)

Thanks for your review of this interesting book! The years between World War 1 and 2 are really interesting, the fight between diverse ideologies.

Sounds like a good book if you want to understand Russia. I am not too aware of Russian politics but only in recent few months I took interest in it. Putting them into my list!

I don’t know much about Russian books, but this one sounds interesting. I love books explores war and colonialism.

Thanks for sharing.