Hello Hivers and Book clubbers,

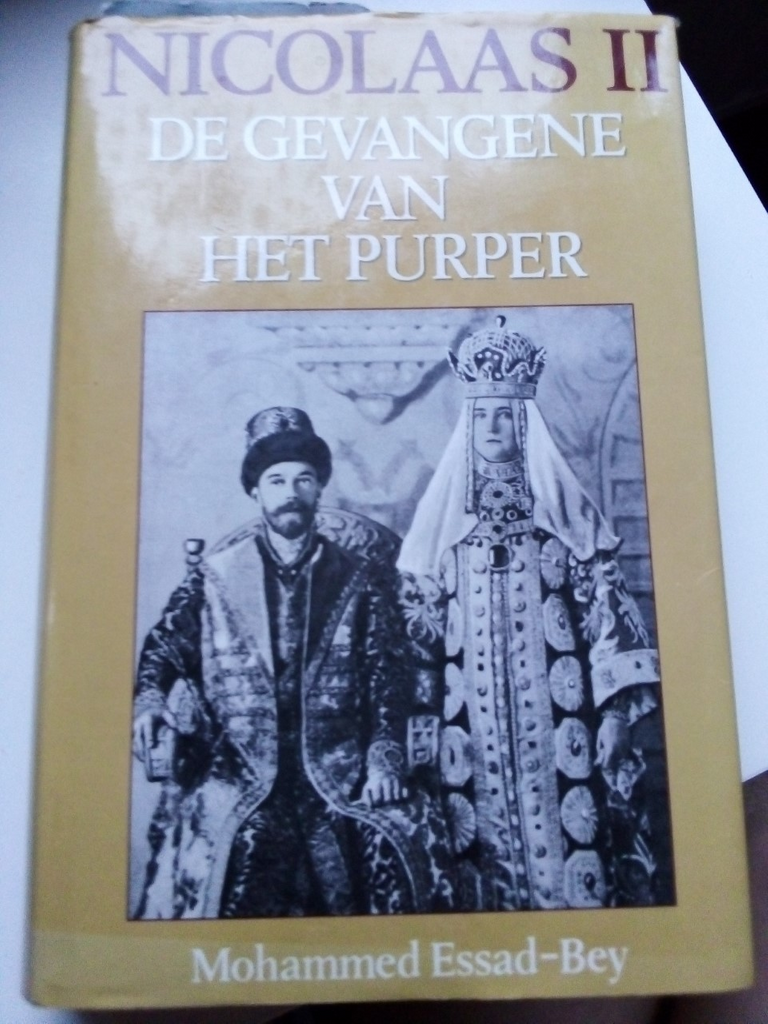

Let's do another book review. I've been reading mostly history books lately, and this one caught my attention when browsing a local store. It's title is 'Nicholas II: Prisoner of the Purple', and is about the life of the last Czar of Russia. My copy is in Dutch, and from the year 1985. The original was written in German in 1935 by Mohammed Essad-Bey, a pen name for Lev Nussimbaum, a Jew who converted to Islam and lived in Germany at the time.

What I can quickly gather from the internet is that Nussimbaum himself has had quite the eventful life, but let's not delve into that this time.

Structure

The book cannot be considered an academical work. The writer has focussed on telling the story, and does it in a somewhat (too) novelized way. As in: he imagines what certain scenes between closed doors might have been/sounded like (for example, between the czar and a certain minister). It would not pass any serious academic critique, but it does make for a more engaging read. And also very importantly: the broad strokes are correct.

One more thing that's important to mention: Nussimbaum is a monarchist, and sympathises with Nicholas II in a way that you would not often see afterwards in modern Western society, which detests both monarchism and non-liberal idea(l)s, which factor in big-time in this story. The book totals about 350 pages, but as mentioned, one reads through it quite effortlessly due to its storytelling.

Background

So let's set the stage a bit first with some background. Russia in the 19th century could be considered a bastion of conservatism. They fought against Napoleon's France, and it was in Russia where Napoleon found his demise due to the freezing winter. France was at the time the center of liberal thought , culture and government. Russia was in many ways still very medieval: Church and State were intertwined, and an absolute monarchy was in place with a Czar that appealed to God for his right to rule the people. Perhaps most remarkable: serfdom (a form of feudalism in which peasants were bound to the land and completely in control of the land-owning class) was still around until 1861, when it was abolished by Alexander II, Nicholas's grandfather.

Alexander II (b. 1818, ruled 1855-1881) is presented by Essad-Bey in the book as a reformer, relatively speaking. The emancipation of the farmers was a good start, at least. Essad-Bey does point out that the reform was not really complete: the system of the mir, a sort of state-owned farm, that came in place of serfdom, combined with the compensation paid to the land-owners by the farmers, made for a situation that unfortunately wasn't that different from serfdom. The peasants were often still bound to the same land and working for the same people, yet now for financial instead of lawful reasons. The peasant issue simmered on for decades, which became a continuous thorn in the side of the Romanov-dynasty.

Alexander II's reformist stance did not pay off for him personally, to put it mildly: he died in 1881 by a terrorist bombing. Brought back to his palace mortally injured, a young Nicholas II, age 13, was there to see his grandfather draw his final breath. A traumatizing experience, surely. Also in the room was Nicholas's father, who now became the new Czar, Alexander III.

Alexander III was no reformist in the slightest: he is described by Essad Bey as having a strong phisique and a strong personality, which usually made things go his way. His personal strenght is what made his autocratic, conservative style to work, even though the clamor for reform, accellerated by events in Europe, was building up further. It was Alexander's decision to have Nicholas join the army as an officer to get a taste of martial life, though he did not teach his son much about the art (if you want to call it that) of ruling. According to Essad-Bey, Alexander III was somewhat taken aback by how different his son was than himself: he grew up to be a somewhat small, quiet man, who did not show particular interest in anything which was to be his role in life.

Personal Reign

Yet that moment was there is 1896, when a 28-year-old Nicholas II succeeded his father. Emperor of the largest empire in the world at the time, no small task, and the people, whether nobles, peasants or burghers waited to see what type of czar he would be. Would he turn reformist, like his grandfather, or would he maintain the status quo, like his father had done?

In short, the answer was the latter. Nicholas was convinced that his right to rule came from God himself, and to compromise by sharing power with something like a parliament would break his promise to God. So he maintained the autocratic style, like his father had. Yet he was much less successful at it. Liberal agitation was rising during his early years: calls for the founding of a parliamant, peasant reform and separation of church and state were among the demands, and Nicholas II did not give in on any point.

He dealt with uprisings and riots the hard way; by letting guards, police and soldiers fire into crowds. A particularly notorious case was that of Bloody Sunaday in 1905, where a priest had rallied a crowd to bring their written demands to the czar himself in St. Petersburg. The response was made by opening fire, and hundreds died.

Interlude

Nicholas II, according to Essad-Bey, was hampered in his decision-making by the immense distance that existed between himself and the common man, be it city-dweller or farmer. Fearing an assassination attempt or terrorist attack like the one that killed his granfather, the Russian court became very secluded; not many people saw Nicholas II and vice versa. How does one rule over a people whose situation he barely knows.

Essad-Bey tells of one anecdote where Nicholas II 'éscaped' his palace unnoticed and went for a day-long walk undercover, so to speak. He found the people to look well-fed, not too poor and healthy. This made quite the impression on him, and he was not wrong per se. There was a catch, however: this happened during his vacation in Crimea, and Crimea was one of the most rich regions in Russia. The further one went north and east, the more poor and dire circumstances became.

I'll put a figurative bookmark at this point, and consider it the half-way for this review. There's still much of this story to tell, and I hope to see you in the next part. If you have comments and questions, they are very welcome. See you all in the next one,

-Pieter Nijmeijer

(Top image: Self made of book cover)

Your content has been voted as a part of Encouragement program. Keep up the good work!

Use Ecency daily to boost your growth on platform!

Support Ecency

Vote for new Proposal

Delegate HP and earn more