Lysander Spooner (1808-1887) was an American philosopher, lawyer, and entrepreneur, as well as one of the leading abolitionists of his time. He even advocated for civilians to forcefully and unlawfully free slaves and assist fugitives in escaping.

His work from 1875, Vices Are Not Crimes, highlights an undeniable distinction to prevent a government from becoming tyranny. It was a compelling read, especially the early pages, which were less structured, before delving into a detailed description of arguments against objections to the freedom to act, even if it may appear immoral or objectionable to others. His arguments are based on his strong opening statements, as he goes straight to the heart of the matter:

"Vices are those acts by which a man harms himself or his property.

Crimes are those acts by which one man harms the person or property of another.

Vices are simply the errors which a man makes in his search after his own happiness. Unlike crimes, they imply no malice toward others, and no interference with their persons or property.

In vices, the very essence of crime—that is, the design to injure the person or property of another—is wanting.

Unless this clear distinction between vices and crimes be made and recognized by the laws, there can be on earth no such thing as individual right, liberty, or property; no such things as the right of one man to the control of his own person and property, and the corresponding and co-equal rights of another man to the control of his own person and property.

https://www.amazon.com/-/es/Lysander-Spooner-ebook/dp/B003EYW1H4

https://www.amazon.com/-/es/Lysander-Spooner-ebook/dp/B003EYW1H4

Regardless of whether we choose the lexical pair crime-vice or any other to designate the same concepts, these are beautiful words defending the idea that each person has their own path in life to seek happiness, and it should not be forcibly hindered. This stands in stark contrast to certain religious phrases that speak of eliminating sins from human souls, moralizing preachers who speak with an arrogant tone as if they were enlightened, or politicians who act as hyper-protective parents and prohibit activities that, according to Spooner's words, would be vices for them but not crimes.

Furthermore, for many actions, it becomes a matter of degree to determine what is virtuous and what is vice. Vice lies in the dosage in such cases, connected to Aristotle's concept of the mean: for example, courage would be the virtuous mean between recklessness and cowardice. However, the same dosage can have different effects on different people, or even on the same person at different times. Moreover, some acts may not reveal their vice until long after they have been practiced, or perhaps they never reveal their vice to a person in their lifetime. Conversely, some acts only reveal their virtuousness in a seemingly distant future that would require great sacrifices in the present.

Can anyone be certain that they have discovered the path to happiness, not only for themselves, as each one knows himself best, but for everyone else? Happiness has been the subject of philosophical discourse since time immemorial, and unanimity has never been reached, and even if it were, it would undoubtedly be temporary. Achieving unanimity would require everyone to have the same premises to make the same deductions for a specific question, and it is already very difficult, if not impossible, to agree on what the relevant set of propositions is in order to make a decision. Moreover, within that same set, it would need to be considered whether all propositions carry the same weight or if some are more relevant than others!

Is it possible to reach unanimity on this judgment of relevance? That would precisely require assuming that there is an identical path to happiness for everyone. While it could be assumed with some confidence that there is a shared DIRECTION for everyone to reach this goal of happiness if we define happiness as a state in which everyone wants to be (with careful consideration of the meanings of these words), some very general elements could be postulated based on the fact that we are of the same species: that we are human beings and share certain things in common.

But let us not forget everything that sets us apart! A multiplicity of personalities, moods, and dispositions! A multiplicity of problems, even if similar or common to the species, manifest in unique ways!

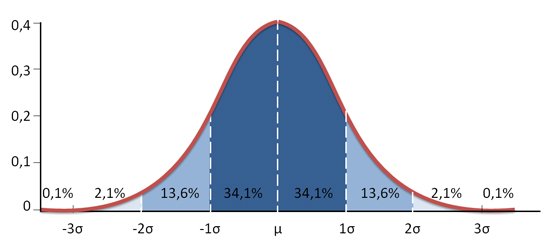

Cultures and philosophies have tried to find those general rules that would be good for everyone, some more generally applicable, others more specific. However, what is good for the general might be detrimental to the exceptional, and many have been inflamed and have also sought to inflame the aggressive sentiments of others against those who do not fit into the aforementioned generality. They target those whose personalities, dispositions, or moods are in the minority and therefore require minority paths in their search.

https://www.master-malaga.com/master-mba/campana-de-gauss/

https://www.master-malaga.com/master-mba/campana-de-gauss/

These individuals on the margins of the Bell curve of the common, even if they commit no crimes and are only vice-ridden (and there is no certainty even in this regard, but assuming there were), become easy targets for inflaming aggressive and tribal tendencies. Does their presence and less common activities create an unpleasant doubt in others about their own paths, leading them to seek external sources of doubt elimination or exclusion instead of seeking confidence within themselves?

After discussing his position in general terms in the early chapters, starting from approximately the halfway point of the work, in chapter 15 out of its 32, Spooner begins to argue against the prohibition of selling items that others use for vice-ridden activities, even if the sellers know they will be used in a vice-ridden manner, contrary to criminally. In the former case, the person would be an accomplice to a vice, and an accomplice cannot be more guilty than the principal agent of a crime. However, a vice is not a crime, and therefore, being an accomplice to it is not a crime either, while selling something knowing it will be used for a crime is a crime by complicity.

From chapter 17 onward, Spooner focuses on the prohibition of alcohol, countering the general argument that the government should prevent people from self-destruction. He provides a detailed response to all the arguments put forth in favor of its prohibition, including an ironic footnote about the legislative wisdom of Massachusetts, which considered a 10-year-old girl capable of deciding to engage in sexual relations but deemed no person capable enough to consume alcohol. Additionally, when elaborating on the topic of alcohol, he further develops the earlier general concepts.

In conclusion, I wouldn't say that the work is completely exhaustive on the topic indicated by its title, but it is likely that nothing is useless in it, and it says a lot and says it well.

Denying someone the ability to act is denying them the opportunity to learn. Spooner expresses the idea of an inescapable individual empiricism necessary for learning, acknowledging that mistakes will be made. The only alternative to free experimentation is tyranny: "I know, and I impose by force that you refrain from doing things that cause no harm to others, and I do not allow you to reject this, which I do for your own good."

...if these questions, which no one can really and truly determine for anybody but himself, are not to be left free and open for experiment by all, each person is deprived of the highest of all his rights as a human being, to wit: his right to inquire, investigate, reason, try experiments, judge, and ascertain for himself, what is, to him, virtue, and what is, to him, vice; in other words. what, on the whole, conduces to his happiness, and what, on the whole, tends to his unhappiness. If this great right is not to be left free and open to all, then each man’s whole right, as a reasoning human being, to “liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” is denied him.

This has been the first work I've read by Spooner and I think I will be reading more

The cover from Amazon is just illustrative, as i read the piece from his volume 5 of his collected works: https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/spooner-the-collected-works-of-lysander-spooner-1834-1886-vol-5-1875-1886-pdf

Lysander Spooner (1808-1887) fue un filósofo, abogado y empresario estadounidense y uno de los principales abolicionistas de su tiempo, defendiendo incluso que los civiles liberaran por la fuerza y contra la ley a los esclavos y ayudaran a los fugitivos a escapar.

Su obra de 1875 Los Vicios no son Crímenes señala una distinción ineludible para que un gobierno no se convierta en tiranía. Me resultó una muy buena lectura, en especial las primeras páginas, que es donde está escrito menos estructuradamente, esto es, antes de ponerse a describir uno a uno los argumentos contra las objeciones a la libertad de actuar aunque para un tercero le parezca malo o inmoral una actuación determinada. Sus argumentaciones están basadas en sus fuertes oraciones iniciales, pues va directo a la cuestión:

Los vicios son aquellos actos mediante los cuales un hombre se perjudica a sí mismo o a su propiedad.

Los crímenes son aquellos actos mediante los cuales un hombre perjudica a la persona o propiedad de otro.

Los vicios son simplemente los errores que un hombre comete en su búsqueda de su propia felicidad. A diferencia de los crímenes, no implican malicia hacia los demás ni interferencia con su persona o propiedad.

En los vicios, falta la esencia misma del crimen, es decir, la intención de dañar la persona o propiedad de otro.

...

A menos que se haga y se reconozca esta clara distinción entre vicios y crímenes mediante las leyes, no puede haber en la tierra tal cosa como el derecho individual, la libertad o la propiedad; no puede haber tal cosa como el derecho de un hombre a controlar su propia persona y propiedad, y los correspondientes y coiguales derechos de otro hombre a controlar su propia persona y propiedad.

https://www.amazon.com/-/es/Lysander-Spooner-ebook/dp/B003EYW1H4

https://www.amazon.com/-/es/Lysander-Spooner-ebook/dp/B003EYW1H4

Independientemente de que elijamos el par léxico crimen-vicio u otro para designar los mismos conceptos, qué bellas palabras en defensa de que cada persona tiene un camino propio en su vida para buscar la felicidad y que no debe impedírsele recorrerlo por la fuerza; compárese con ciertas frases religiosas que hablen de eliminar los pecados de las almas humanas, con los moralistas-sermoneantes que hablan con tono de arrogantes iluminados, o compárese con los políticos que hablan como padres hiperproteccionistas y prohíben actividades que bajo las palabras de Spooner serían vicios para ellos, quizá no para otros, pero que no son crímenes.

Súmese que, además, para muchos actos es una cuestión de grado qué es virtud y qué es vicio. El vicio está en la dosis en tales casos, puede decirse, conectado esto también con ese punto medio del que hablaba Aristóteles: p. ej., la valentía sería el virtuoso punto medio entre la temeridad y la cobardía. Pero mismas dosis pueden tener efectos distintos en distintas personas, e incluso en una misma persona en diferentes momentos. También, hay actos que no se revelan como vicios hasta mucho tiempo después de haberlos practicado, o acaso nunca para una persona en su vida; y otros actos no revelan su virtuosidad sino en un futuro que parece muy lejano y que requeriría grandes sacrificios en el presente.

¿Acaso alguien puede estar seguro de que ha descubierto el camino de la felicidad, no ya solo para sí mismo, que es a quien más conoce uno, sino para todos los demás? La felicidad ha sido objeto de disquisiciones filosóficas desde siempre y nunca se ha estado ni cerca de una unanimidad que, de todos modos, de alcanzarse seguramente sería transitoria, pues para alcanzar la unanimidad haría falta que, para una cuestión concreta, todos tuvieran las mismas premisas para poder hacer la misma deducción, y si ya es muy difícil, sino imposible, que se acuerde cuál es el conjunto de proposiciones relevantes para tomar una decisión, ¡después aún habría que ponderar dentro de ese mismo conjunto si todas tienen el mismo peso o unas son más relevantes que otras!

¿Puede llegar a haber unanimidad en este juicio de relevancia? Eso, justamente, requeriría asumir que hay un idéntico camino de la felicidad para todos. Pero, mientras que podría asumirse con alguna confianza que hay una misma DIRECCIÓN para todos para llegar a esta meta de la felicidad si definimos la felicidad como un estado en el que todos quieren estar (con cuidado de qué significados tengan estas palabras), podrían llegar a postularse algunos elementos muy generales basados en que somos de la misma especie: que somos seres humanos y tenemos cosas en común.

¡Pero que eso no nos haga olvidar todo lo que tenemos distinto! ¡Multiplicidad de personalidades, de ánimos, de disposiciones! ¡Multiplicidad de problemas, aun si similares o comunes a la especie, se manifiestan de formas únicas!

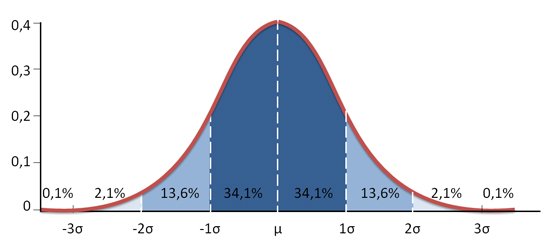

Las culturas y filosofías han tratado de encontrar esas reglas generales que sean buenas para todos, unas con más generalidad, otras con más especificidad. Pero lo general es bueno para lo general y malo para lo excepcional, y muchos se han visto inflamados y también han tratado de inflamar los sentimientos agresivos de los demás contra aquellos que no caben en la generalidad apuntada, con aquellos cuyas personalidades, disposiciones o ánimos son minoritarios y requieren, por ende, caminos minoritarios en su búsqueda.

https://www.master-malaga.com/master-mba/campana-de-gauss/

https://www.master-malaga.com/master-mba/campana-de-gauss/

Fáciles blancos aglutinadores de las tendencias agresivas y tribalistas son estas personas en los márgenes de la campana de Gauss de lo común aunque no cometan crímenes y sólo sean viciosos (y no hay certeza de esto último tampoco, pero aún asumiendo que se la tuviera). ¿Acaso su presencia y actividades menos comunes les crean una duda desagradable a los demás sobre sus propios caminos y, en vez de buscar la confianza en su interior, buscan eliminar o apartar la fuente externa de la duda?

Tras hablar de su posición en términos generales en los primeros capítulos, a partir de aprox. la mitad de la obra, en el capítulo 15 de los 32 de ella, empieza Spooner a argumentar contra prohibir la venta de elementos que otros usan para actividades viciosas, aun si los vendedores saben que los usarán viciosamente, contrario a criminalmente: en el primer caso, la persona sería cómplice de un vicio, y un cómplice no puede ser más culpable que el agente principal de un crimen, pero un vicio no es crimen y, por lo tanto, tampoco lo es ser su cómplice, mientras que sí es un crimen por complicidad vender algo sabiendo que sí será utilizado para un crimen.

Y a partir del capítulo 17 Spooner se concentra en la prohibición del alcohol, contra el argumento general de que el gobierno debería evitar que las personas se autodestruyan, contestando detalladamente todos los argumentos esgrimidos para su prohibición, incluyendo una ironía en una nota al pie sobre qué ejemplo era de la sabiduría legislativa de Massachusetts que se consideraba como con capacidad suficiente a una niña de 10 años para que decida tener relaciones sexuales pero que ninguna persona era considerada como con capacidad suficiente para tomar alcohol. Además, al elaborar sobre el tema del alcohol desarrolla más los conceptos generales previos.

Concluyendo: No diría yo que la obra sea completa sobre el tema del título, pero sí es probable que no le sobre nada, y además dice mucho y muy bien.

Negarle a alguien actuar es negarle aprender: manifiesta Spooner la idea de un inescapable empirismo individual necesario para aprender, a sabiendas de que se comenten fallas, pero la única alternativa a la libre prueba es la tiranía: "Yo sé, yo te impongo por la fuerza que no hagas cosas aunque no dañen a otros y yo no te permito que rechaces esto que hago por tu propio bien".

“Si estas preguntas, que nadie puede realmente y verdaderamente determinar por nadie más que por sí mismo, no se dejan libres y abiertas para experimentar por todos, cada persona se ve privada del más alto de todos sus derechos como ser humano, a saber: su derecho a indagar, investigar, razonar, probar experimentos, juzgar y determinar por sí mismo qué es, para él, la virtud y qué es, para él, el vicio; en otras palabras, lo que, en general, conduce a su felicidad y lo que, en general, tiende a su infelicidad. Si este gran derecho no se deja libre y abierto para todos, entonces se le niega a cada hombre su derecho completo, como ser humano razonante, a la "libertad y búsqueda de la felicidad”

Este ha sido el primer trabajo que he leído de Spooner y creo que seguiré leyendo más (también pueden encontrarse traducciones al español gratuitas en internet).La portada de Amazon es solo ilustrativa, ya que leí el texto del quinto volumen de sus obras completas: https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/spooner-the-collected-works-of-lysander-spooner-1834-1886-vol-5-1875-1886-pdf