Alice:

Critical race theory is an outgrowth of critical theory. Critical legal studies was indeed popular in 1970s law schools, but critical theory didn't start there. This is, like, critical theory 101:

Critical Theory has a narrow and a broad meaning in philosophy and in the history of the social sciences. “Critical Theory” in the narrow sense designates several generations of German philosophers and social theorists in the Western European Marxist tradition known as the Frankfurt School. According to these theorists, a “critical” theory may be distinguished from a “traditional” theory according to a specific practical purpose: a theory is critical to the extent that it seeks human “emancipation from slavery”, acts as a “liberating … influence”, and works “to create a world which satisfies the needs and powers of” human beings (Horkheimer 1972b [1992, 246]). Because such theories aim to explain and transform all the circumstances that enslave human beings, many “critical theories” in the broader sense have been developed. They have emerged in connection with the many social movements that identify varied dimensions of the domination of human beings in modern societies. In both the broad and the narrow senses, however, a critical theory provides the descriptive and normative bases for social inquiry aimed at decreasing domination and increasing freedom in all their forms.

I am sympathetic to your friend's aims, probably, but the essay is riddled with preventable errors of exactly this nature, i.e. "this student has not done the reading." To pick one easy example,

Women make 82 cents on the dollar compared to men for doing the same job.

This is false, and the link your friend included there does not support it. Women, in aggregate, make 82% of what men make, and the vast majority of the discrepancy disappears when you make the simple adjustment, "doing the same job." Men and women doing the same job almost always make the same amount of money, and when they don't there are often other explanations to account for the difference. When those explanations don't exist, you have a successful lawsuit on your hands.

I have a number of objections to critical theory, many overlapping with your friend's concerns, so I don't want to seem unnecessarily hostile here. But your friend has scarcely even discovered the problem, I think. More effort will be required to achieve a thorough understanding of it.

Bob:

I have a number of objections to critical theory

Given your status as a philosopher my genuine "internet friend", do you mind elaborating and/or linking to something that better discusses your objections to critical theory?

I ask because I recently finished Cynical Theories and have found myself wanting. The book certainly helped me understand better what critical theory and its progeny disciplines1 actually are, but I am left wanting for a proper academic critique of critical theory itself (as such?). I can muster my own critiques form a scientific (positivist?) perspective2 , as well as personal/anecdotal ones3 , but I don't think this is enough. I ask not purely out of curiosity, but out of the increasing need to be able to actually give an answer to why I object to the lens of critical theory4 that isn't made up on the spot. If you could point me in the right direction, this would be very helpful.

1 - Queer theory, postcolonial theory, critical race theory, fat studies, certain types of feminism, etc.

2 - We, and our language, and the emergent discourses are actually damn good at communicating about objective reality. I wouldn't be in danger of being fucking scooped if this wasn't the case. For the record, my paper is much, much better and is looking to go out in time to avoid it. But god damn hasn't it ruined my July and August.

3 - confusing is for ought is damn near in meaning to the best advice I received in grad school: don't be wedded to you hypothesis

4 - My girlfriend was recently asked if she'd like to receive training to teach a course on how to "critically" read scientific literature as part of her position in our local "Women and Minorities in Science" group. She declined, and we mostly on the same page about this stuff, but unless I go full Kolmogorov I need to be able to give an answer of why this stuff is wrong headed more than "this lens tells us exactly nothing about objective reality"

Alice:

Well, I'm happy to try, anyway!

I am left wanting for a proper academic critique of critical theory itself (as such?).

I think the first thing you have to grasp here is that there isn't a "critical theory as such." To quote further from the SEP link I shared above:

The philosophical problem that emerges in critical social inquiry is to identify precisely those features of its theories, methods, and norms that are sufficient to underwrite social criticism. A closer examination of paradigmatic works across the whole tradition ... reveals neither some distinctive form of explanation nor a special methodology that provides the necessary and sufficient conditions for such inquiry. Rather, the best such works employ a variety of methods and styles of explanation and are often interdisciplinary in their mode of research. What then gives them their common orientation and makes them all works of critical social science?

There are two common, general answers to the question of what defines these distinctive features of critical social inquiry: one practical and the other theoretical. The latter claims that critical social inquiry ought to employ a distinctive theory that unifies such diverse approaches and explanations. On this view, Critical Theory constitutes a comprehensive social theory that will unify the social sciences and underwrite the superiority of the critic. The first generation of Frankfurt School Critical Theory sought such a theory in vain before dropping claims to social science as central to their program in the late 1940s.... By contrast, according to the practical approach, theories are distinguished by the form of politics in which they can be embedded and the method of verification that this politics entails. But to claim that critical social science is best unified practically and politically rather than theoretically or epistemically is not to reduce it simply to democratic politics. It becomes rather the mode of inquiry that participants may adopt in their social relations to others. The latter approach has been developed by Habermas and is now favored by Critical Theorists.

This is... well, I have a hard time following it unless I read very slowly, so I can only imagine what it looks like to non-philosophers. But at the risk of being slightly uncharitable to the SEP author, reading between the lines you get something like the following:

Methods of literary criticism (especially, deconstruction a la Derrida) were applied to the pursuit of social criticism--in particular, to "fight oppression"

Early practitioners of this new form of social criticism sought a comprehensive social theory that would validate their political preferences

It was realized that any such theory would itself be subject to the techniques of social criticism

Therefore, attempts to develop that theory were abandoned in favor of using "whatever works" (in practical terms, this means rhetoric) to achieve one's practical (political) aims

The most explicit essay I can think of on this matter is Stanley Fish's Boutique Multiculturalism. Note, Fish is a literary theorist by training, but he is also a professor of law at Florida International University, and well known in legal theory circles. His argument in Boutique Multiculturalism is that all judges ever do--all anyone making arguments ever does--is "ad hoccery," that is, making arguments in hopes of advancing our political agendas. And he very much endorses this: objectivity is a lie, impartiality is a lie, but hey, as long as it's a lie in furtherance of the right results, who cares? Just do it! Since "critical theory" is (now deliberately) not a theory, there's nothing there to criticize "as such"--there are only particular instances which must be judged on their own merits, so every argument is just a political fight over the facts of power (and there are a dizzying array of "responses" to be made).

I can't remember which book it is in (and I'm not in my office to check right now) but I'm pretty sure it was Richard Posner who made the most direct response to Fish on this matter. His response, to the best of my recollection, was something like, "okay, so, it's definitely true that we are all working from a certain social milieu. But we can still rest the legitimacy of principled legal reasoning on the effort to be impartial. There are good reasons (and ways) for judges to seek objectivity, even if they inevitably fall short."

Whether or not you are moved by Posner's response, I think it frames the challenge of "critical theory" more generally quite well: critical theorists are fundamentally, inescapably, moral anti-realists. Which is a really weird thing to be when you are arguing for specific, practical moral conclusions as correct. But the starting point for basically all critical theory is "I spy oppression." Having spotted oppression, we go back to the SEP article:

[A] critical theory is adequate only if it meets three criteria: it must be explanatory, practical, and normative, all at the same time. That is, it must explain what is wrong with current social reality, identify the actors to change it, and provide both clear norms for criticism and achievable practical goals for social transformation.

If I feel oppressed by, say, the existence of Barbie Dolls, one thing I could conclude is that other people have tastes in toys that make me uncomfortable, but there's nothing wrong with that, and also there's nothing to be done about it. But instead I could say, "EXPLANATION people like Barbie Dolls because there is a nebulous force, called patriarchy, that approved of hypersexualizing women in every possible context, NORMATIVITY the dominance of patriarchy is wrong, and PRACTICAL RESPONSE depictions of unrealistically idealized female bodies should be eliminated from public and private display."

It would be perfectly natural for a moral philosopher who was not a critical theorist to ask after the nature of "patriarchy," and what makes the influence of patriarchy wrong, and what is supposed to replace if it is cast down, and so forth. But that philosopher would then simply be accused of having a "hostile epistemology" or some similar bullshit excuse to refuse to engage on the merits. And really, that's what critical theory is, in the technical, Harry Frankfurt sense: an intention to persuade, without regard for the truth. As the Wikipedia entry summarizes:

The liar cares about the truth and attempts to hide it; the bullshitter doesn't care if what he or she says is true or false, but cares only whether the listener is persuaded.

Given the definitions I'm relying on here, you can't do critical theory unless you are specifically aiming at some perceived "oppression." But there is no value, in critical theory, to establishing as a matter of fact that oppression is actually occurring. Indeed, many critical theories explicitly disclaim the value of empirical evidence. A lot of stuff written on "microaggressions" demonstrates this, because if you can produce evidence of actual prejudice, then you have a "macro" aggression. True "micro" aggressions by their very nature cannot be empirically proven, because if they could, they would simply be aggressions. So if someone asks you where you're from, you can answer their question to the best of your ability... or you can feel oppressed that someone would sneakily imply that you might be a foreigner! In this way, critical theory tends to beg the question of oppression, and there are a number of rhetorical moves (the phrase "victim blaming" in particular) in use that obfuscate the problem.

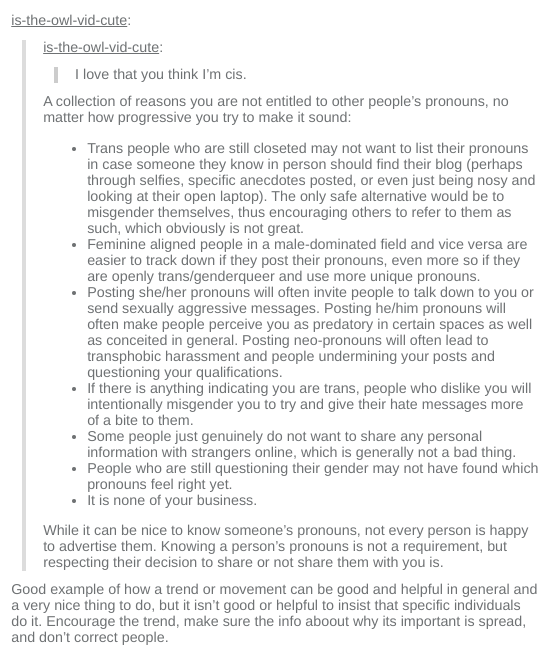

And the thing is--none of this is to suggest that critical theorists aren't fighting oppression. Begging the question is an informal fallacy; you can beg the question and still be right. But someone else might face the same situation as you and draw wildly different conclusions; since there is no theory of "critical theory," there's no "wrong way" to do it. I really enjoyed, for example, this list of reasons to not advertise your pronouns

It's a whole list of reasons why pronoun advertising is oppressive. It aims to persuade people to not advertise their pronouns as a result, completely opposite what you might assume "critical theory" to conclude about pronoun advertising. If you can use critical theory to come to whatever conclusion you prefer, then what, exactly, is the point? Well, obviously, the point is to win (certain) arguments!

The foregoing also helps to contextualize the real problem with certain conservative attempts to "ban" critical theory in K-12 education. You can ban specific works of critical theory, of course! You could even ban the teaching of certain conclusions that are justified, in some contexts, by appeal to critical theory. But since critical theory isn't any one thing in particular, this is a game of whack-a-mole.

Does that seem helpful at all? There are so many moving parts that it is hard to paint a clear picture of the problem, I think, but if you absolutely had to pin me down on an elevator pitch response to critical theory, I would say "it is a self-undermining form of rhetoric, in no way truth-seeking, and is consequently corrosive to all social institutions, including the ones it purports to favor."

Bob:

I have had some time to chew this over (and google more) and I think I am at least closer to grasping what is going on.

Please correct me if I am wrong, but it seems to me that critical theory is at least in some sense a method rather than a cohesive school of thought, defined more by a certain set of rhetorical techniques than any particular underlying axioms1. Those who created what we call "critical theory" did this on purpose, to prevent their own scholarship from being attacked in a similar manner. Depressingly, the occasionally uttered phrase "there are no bad methods, only bad targets" makes much more sense in this context.

As you further flesh out in your comment below, two things I dread the most regarding disciplines making heavy use of critical theor(ies?) is a) the sense that they can only tear down the work of others (and will be deployed wantonly on the good and the bad alike) and b) that it all comes off as rhetorical bullshit. Like an internet troll, one could go through line by line attempting to shown how wrongheaded an assertion is only for them to endlessly deny the words you use mean anything and imply that you are an oppressor. Yes, this make me worried over a certain object level political battles within the University. But more than that, coming from working in the hard science I just have trouble grasping how anyone could use such methods and then go home and look at themselves in the mirror. My job is to describe the universe as I see it, which hopefully more times than not matches the way it really is. How and why some one would throw it a way to play word games is just baffling.

Also, if you don't mind a follow up question, could you elaborate on precisely what you mean by "moral anti-realist"?

1 - other than perhaps a distrust or rejection of most peoples notions of "truth" by labeling them as the products of "dominant discourses", though perhaps this is more "postmodernism". The two concept seem closely related too me and at times used in popular discussion interchangeably, though I can't tell if the people using them this way are actually correct when they do so.

Alice:

Sounds like you've understood me! In response to your footnote, one thing to remember about "postmodernism" is that it is a word that applies to many different developments in many different fields; the common strand is something like a rejection of the notion of progressively-increasing correctness through adherence to established narratives, methods, truths, social arrangements, etc. So in art this manifests as "art doesn't have to be about anything" but in philosophy it manifests as "truth is radically subjective." Not all (not even most) postmodernism is critical theory, but all critical theory is postmodernism.

My job is to describe the universe as I see it, which hopefully more times than not matches the way it really is. How and why some one would throw it a way to play word games is just baffling.

Ironically, critical theory answers your question: they play word games because word games can, may, or do give them power (or at least, a feeling of power) over their own lives. This video from five years ago remains relevant today; here you have someone outright denying the validity of science to argue that shamanistic tradition is just another way of "knowing" things. But the subtext in this exchange is completely disconnected from the science itself. The person raising the objection may think he is defending the "objective truth" but what he's really doing, according to the critical theorist, is asserting his superiority and the superiority of western thought. Shouting him down is not an act of denying the truth of his words, it is an act of putting him in his place, i.e. subjugating him. Their likely response would be something like "we're not subjugating him, we're un-subjugating ourselves." Another real-life example would be the Communist purge of intellectuals, including doctors and scientists, in China (etc.). A fictional example would be the scene in Black Panther where the warriors all make monkey noises to shut down the white guy (who is in fact being reasonable and helpful) and then tell him "you do not get to speak here."

Thus, paradoxically, critical theory is a bunch of intellectuals being fundamentally anti-intellectual. They are, I think, confused, because scientists like you do not pursue science with an intent to dominate others. But knowing what others do not gives you abilities, gives you power, others do not have, and if that makes them feel small, it is easier for them to tear you down than to simply follow the same path you took to gain power for themselves. This is where the political right derives phrases like "the gospel of envy"--it's not just about the stuff rich people have, it is about tearing down power in an attempt to be (really, to feel) free. Because if everyone is miserable, then maybe your misery is not your own damn fault. If science can cure your cancer but voodoo can't, then maybe you should give respect to the people whose lifestyle you hate, whose choices you deride, etc.--and this conclusion is painful to bear.

Also, if you don't mind a follow up question, could you elaborate on precisely what you mean by "moral anti-realist"?

Moral realism is a collection of positions that, while disputing the particulars, agree that moral claims can be in some sense "true," rather than being e.g. merely matters of preference. Moral anti-realists argue from numerous angles that this is incorrect; that claims like "slavery is wrong" lack a truth value.

(In hopes of not being misunderstood, perhaps a simple lesson in logic is warranted here. In philosophy, the word "statement" is a term of art for a sentence with a truth value. "The cat is purple" is a statement, and it is either true (just in case it coincides with reality) or it is false. You may not know whether the cat is purple; you may not be able in practical fact to ascertain the cat's color; nevertheless you know that there are only two possibilities: either the cat is purple, or it is not, and so the truth value of the statement must be either true, or false. I here set aside arguments about the possibility of an excluded middle. Many sentences lack a truth value; they might be questions, or they might be exclamations, or they might be nonsense. These are not statements. So another way of describing moral anti-realism is to say that moral anti-realists do not think that moral claims are statements at all, even though moral claims typically look like statements.)

Critical theory often begins with assertions about how "morality" is really just window-dressing on the facts of power; moral claims are social structures implemented by the strong to subjugate the weak. This is a kind of moral anti-realism, insofar as it asserts that morality is objectionable not because someone got it wrong, but because morality is just a tool of oppression that either works or doesn't work--not a set of claims with truth values. What is amazing about this argument is that it is one of the main things Plato sets out to refute in the Republic. It is an absolutely ancient view, purportedly held by the sophists of Athens, and defended--of course--through use of rhetoric. The more things change, the more they stay the same!

But critical theory typically ends with assertions about who should be put into power instead, and these claims are made as if their truth had somehow been established along the way. Having broken down the patriarchy, it is concluded that "therefore women should be empowered in thus-and-such a way." Having broken down white supremacy, it is concluded that "therefore blacks should be empowered in thus-and-such a way." But these are moral claims--they are claims about what ought to be done. If they are held to be true claims, then the critical theorist is suddenly behaving like a moral realist instead of a moral anti-realist. This is structurally similar to the skeptic's dilemma posed by Plato 2500 years ago. Philosophers sometimes call this a "performative contradiction," where your behavior seems like good evidence that you don't believe what you claim to believe.

Bob:

So continuing this line of thought (if I'm not being a burden), I have two further questions.

- If the term Critical Theory with a capital C/T describes a set of methods, rather than any particular school of thought, then the obvious next question is what exactly are those methods specifically? Or is this to left deliberately undefined (and if so, why can't anything claim it is a critical theory)? You alluded to this at least tangentially when you state that a Critical Theory needs to be "explanatory, normative, and practical." However, thinking it over I'm not sure this is enough to distinguish Critical Theory from any other scholarship at least based on my unorganized perceptions of it.1 Aiming towards alleviated oppression seems to fit, but my understanding of what has been called "The Liberal Project" also sought to do this by granting everyone individual rights. "Deconstruction" might perhaps be another method used by Critical Theory, but much like you mentioned in you discussion of postmodernism it seems to mean many different things in different contexts. I was once served a "deconstructed burrito" and a boogie Mexican restaurant (which as far as I could tell was essentially just fajitas), but insisting that this "deconstruction" in the sense meant philosophically is likely misguided. Some discussion of "power"2 seems apt here, but I am unsure if this shouldn't be ascribed to the 1970s postmodernism, rather than Critical Theory.

Edit: An having reread everything, you do mention in one sense that Critical Theory is "whatever works" rhetorically. But this doesn't exactly seem like a satisfactory answer either, even if it turns out to be true.

- I still find myself search for some unifying thread running through the humanities disciplines that make use of Critical Theory as well as later works of postmodernism (Foucault and Derrida, specifically). As the Ross Douthat article you linked mentions, there is no specific reason why Critical Theory can only by used by the academic left, and indeed the behavior of the Trumpian Right seems to parallel it closely (though I am unconvinced anyone at Turning Point USA is reading gay left wing French academics from the 1970s, let alone ones from German Jews in the 1930s and 1940s). Yet despite this, scholars in the fields labeled "grievance studies" (and perhaps the humanities more broadly, though I'm less willing to commit to this) all seem to be nominally on the same page about a number of issues, across fields, when there is really no reason their methodologies should ever lead them to the same conclusions.3 Why should postcolonial scholars get along just fine with someone in the English department, given that I could use the tools of Critical Theory to read Conrad's Heart of Darkness not as an indictment of the evils of colonialism, but as illustration of the dangers of "going native". Why should someone inf the Afro-American Studies department not be the ideological enemy of the Queer theorist, given certain elements of black culture still maintain negative opinions on homosexuality? Why do any of them tolerate Fat Studies? Is it purely social pressure? Or perhaps their proximity to each other given that they all work at Universities? In other words is it purely that these ideas, created first in Universities, spread first to individuals who a priori shared the same principles and that they all just haven't deconstructed their way into becoming mortal enemies yet?

1 - For example, are the biological and medical sciences establishing a Critical Theory by asserting: SARS-CoV-2 is responsible for the disease referred to as COVID19 (Explanation) and allowing the virus to spread unchecked across the world threatens the health of everyone (Normative), and thus we need to institute lock-downs and develop a vaccine (Practical Response). Of these, I feel like the only aspect I struggled in coming up with in this example is the "Normative" aspect, though I am unsure if this is me arriving at genuine distinct aspect of a Critical Theory and thus am forced to stretch the definition of Normative or merely me writing this late in the evening.

2 - According to Cynical Theories, which I mentioned reading, there is both a Postmodern Power Principle (society is made up of interlocking systems of power that seek to advantage dominate groups and oppress minority ones) and a Postmodern Knowledge Principle (Knowledge is culturally constructed by dominant groups as justify their power) which underlie and unify grievance studies departments, but I am unsure if these were synthesized from the authors or would be recognized academically. Also they are Postmodern principles, not Critical principles, which seems to be telling.

3 - While circular left wing firing squads, status games, and personal conflict are certainly still pervasive (Critical Theorists are still humans after all), the only major intellectual/ideological disagreement I am aware of are between intersectional feminists and older schools of thought like gender abolitionism, who divide strongly over issues regarding transgenderism.

Alice:

If the term Critical Theory with a capital C/T describes a set of methods, rather than any particular school of thought, then the obvious next question is what exactly are those methods specifically?

Good question. I think the textbook historical answer is something like "critical theory borrows the methods of deconstruction and sociology in pursuit of specific political ends." Historically, at least, deconstruction a la Derrida is where "Critical Theory" got its start--by borrowing from literary theory. I'm not a Derrida scholar, but I've been told that Derrida himself thought this was a bad idea, since the Crits were using his methods to argue for concrete social conclusions, when the whole point of his method was to destabilize meaning in order to explore a text. Finding new ways to read Shakespeare has very different consequences than finding new ways to read the Constitution; there isn't much of practical importance that relies on the stability of Shakespearean interpretation, while rather a lot depends on the stability of Constitutional interpretation.

To get a little more specific, one of the most commonly-discussed methods of deconstruction is the breaking down of "opposites." I'm going to do this a little badly, I think, because I am far outside my wheelhouse when it comes to Continental thought, but consider Hamlet's question, "to be or not to be." These are offered as a comprehensive list of available options; either he's going to kill himself, or not! But actually one thing Hamlet could be is a corpse, and one thing Hamlet could not be is dead. The easy, surface interpretation of "should I live or should I die" has now been totally inverted, to "should I die or should I live?" This case perhaps presents a distinction without a difference, but it suggests that the specific meaning of the text is unstable--that you can't just say "to be" means "to live." So why didn't Shakespeare write "to live or not to live?" But that might not be an improvement, after all; witness "get busy living or get busy dying." Is life merely the perpetuation of biological function? Or is life something more? And can that "more" be fully realized by dying? In fact it looks like Hamlet himself is deconstructing the notion of "life," here. Pad this out for a couple of paragraphs and you've got yourself a publishable essay!

Now consider the "opposites" of public property, and private property. This is a crucial distinction in the law. But what, ultimately, makes something "private property?" We sometimes say that private property has an exclusionary character, that is, it is reserved for the exclusive use of some person or organization. But its very existence requires a public that has agreed to preserve for one person's (or organization's) exclusive use. That is, in a hypothetical "state of nature" your only claim to "private property" is whatever you can successfully prevent others from seizing. But in a legal regime, your private property is a public grant; you don't have to personally prevent others from using it, because public resources will (at least theoretically) be expended to guarantee your "private" use of that property. So isn't all private property really a kind of "public" property, within a system of laws? Isn't it actually the public deciding who can be excluded from that property? Doesn't that mean it would be perfectly legitimate for us to restructure "private property" in whatever way we like? By highlighting features we ordinarily take for granted and using them to destabilize our sense that we "know" what private property is, deconstruction strengthens the idea that things could be done differently. What Crits tend to gloss over is that there are costs to "doing things differently," and it's not at all obvious whether different would genuinely be better, or whether any of our other values would be likely to survive the transition.

The methods of sociology play a similar role. Sociologists investigate groups of humans, and explain phenomena in terms of group interactions. This is by no means the only lens through which human behavior can be understood and explained, but a questionable platitude of sociology (and especially business schools) is that "if you can't measure it, you can't improve it," which gets fallaciously inverted to "if you can measure it, you can manage (i.e. improve) it."

Note however that these methods were just a starting point, and the vast majority of "scholars" engaged in the Critical "project" are actually pretty bad at using them. Consider this essay from 20 years ago. It is in some ways an exceptional piece, but in some ways it is rather exceptionally shitty. The author is thorough in her historical examination of the topic of private property rights, but she plays very loosely with the methods of deconstruction she herself elaborates in the introductory sections. Footnote 4 actually captures what I suspect is her central problem:

By "unpack," I mean "deconstruct" not "in the technical sense used by critical legal scholars influenced by Jacques Derrida ... but in the emerging popular sense of deconstructing a social phenomenon into its component parts."

And indeed, though she elaborates on Derrida's methods, the conclusion of her essay is extraordinarily bland--much more a matter of "taking apart" than of "deconstructing." All she really succeeds in doing is breaking down certain historical phenomena into their component parts. Is this a successful work of "Critical Legal Theory?" I'm not sure I could say yes or no with any real confidence. She clearly wants to play the game, she's clearly read the rules. But it's not quite obvious to me that she really understands how to play. Or maybe more likely: the game she's really playing is the "get published" game, and so even though some deconstruction and sociology makes its way into her paper, there's a whole bunch of other stuff going on, too. And if enough of the people writing "critical theory" take it in enough different directions for similar reasons, eventually the mass of scholarship recognized as "critical theory" is going to get extremely fuzzy, and not just around the edges!

You alluded to this at least tangentially when you state that a Critical Theory needs to be "explanatory, normative, and practical." However, thinking it over I'm not sure this is enough to distinguish Critical Theory from any other scholarship at least based on my unorganized perceptions of it.

Yeah, those appear to be necessary conditions, but not sufficient ones.

An having reread everything, you do mention in one sense that Critical Theory is "whatever works" rhetorically. But this doesn't exactly seem like a satisfactory answer either, even if it turns out to be true.

I have never been able to get a satisfactory answer about this, to the point where I suspect it is kind of the point. When you're talking to people whose priority is to win arguments, it is hard to know how seriously to take their responses to questions about their methods. One reason I appreciate the Fish essay I mentioned earlier is that it is the most explicit example I have of someone who is arguably a critical theorist coming right out and saying, essentially, "winning is the point, and there's really no need to pretend otherwise."

As the Ross Douthat article you linked mentions, there is no specific reason why Critical Theory can only by used by the academic left, and indeed the behavior of the Trumpian Right seems to parallel it closely (though I am unconvinced anyone at Turning Point USA is reading gay left wing French academics from the 1970s, let alone ones from German Jews in the 1930s and 1940s).

Right, but this only further muddies the waters of "what counts" as Critical Theory, and it is hard to discuss the phenomenon without resorting to sociology! My own training suggests that the answer is "meme magic." The Trumpian Right doesn't read Foucault, but they don't have to; they just have to imitate the kinds of maneuvers they see working for their opponents. When you throw a bunch of memetic superweapons into an arena and let them duke it out, Darwin style, the memes that emerge from the fray require no awareness of their ancestors. Indeed, tracing the evolution of these ideas in a precise way is an act of intellectual archaeology. Or maybe a better comparison would be digging in to the "black box" of iterative machine learning.

In other words is it purely that these ideas, created first in Universities, spread first to individuals who a priori shared the same principles and that they all just haven't deconstructed their way into becoming mortal enemies yet?

This seems basically correct, I think. Deconstruction is just not how people normally approach relationships. It is one thing to deconstruct a centuries-old text. It is quite another to insist that the person paying you a compliment is actually oppressing you. Deconstructing live interactions is a hostile act. It's a way of refusing to play the game of social expectations--and, often, a way of demanding that others conform their behavior to your preferences, rather than tacitly agreeing to negotiate a shared social environment.

But even most Critical Theorists don't actually live their lives this way. They selectively apply deconstruction or sociology or rhetoric or whatever to their enemies, suggesting to me that they generally recognize, at some level, that critical theory is a weaponized theory, not merely a tool for truth-seeking. This is also where you get the comedic stereotypes of the radical feminist who subs for Chad, or the avowed Communist who Tweets about abolishing private property from her gated mansion in Beverly Hills, etc. Or, in the other direction, you get Key & Peele's Office Homophobe.

According to Cynical Theories, which I mentioned reading, there is both a Postmodern Power Principle (society is made up of interlocking systems of power that seek to advantage dominate groups and oppress minority ones) and a Postmodern Knowledge Principle (Knowledge is culturally constructed by dominant groups as justify their power) which underlie and unify grievance studies departments, but I am unsure if these were synthesized from the authors or would be recognized academically. Also they are Postmodern principles, not Critical principles, which seems to be telling.

I think it is a mistake to call these Postmodern principles. Postmodernism is substantially about transcending the very notion of stable social "principles." This is related to the idea that it is contradictory to use deconstruction to reach firm conclusions. Both the Power Principle and the Knowledge Principle offered here are Critical principles--they are the firm conclusions Crits purport to have arrived at by way of Postmodernism. But a principled adherence to Postmodernism would say "it's more complicated than that." A hypothetical "pure PoMo" scholar might very well agree that certain groups are oppressed by certain power structures, but e.g. Foucault observed the existence of systems of power that sought to overcome dominant groups and advantage minority ones. The contribution Postmodernism makes to Critical Theory here is to say, "there's no reason you can't just stop privileging these power structures here, and start privileging those over there instead."