Note: This is an epic article - grab a coffee/beer and settle in to learn all about...

Choosing The Best Mastering Volume – How Loud Should My Master Be In 2022?

Topics covered:

- How loud should my album be in 2022

- Different playback methods & why it matters

- The simplest explanation of LUFS on the internet!

- The difference between Peak Level and True Peak

- The best LUFS for mastering

- The best mastering level for streaming

- Why only using numbers isn't the best approach

- Official loudness targets for different streaming platforms

- How to "Win" the loudness war in 2022 and beyond

Let's get into it...

There are several different opinions on the question of “What is the best volume to finish my master?” (or for the more technically minded “What LUFS should I master to?”).

We can’t avoid mentioning the famous loudness wars in this article either, and the direction music mastering is heading. After many years spent racing towards the loudest master, is the loudness war over?

Having been a professional full-time mastering engineer since 2006, I have a few opinions. I’m going to give my perspective on these questions and explain about LUFS, peak and true-peak (with as little jargon as possible).

The end point is finding the ultimate recipe for the best mixing and mastering finish for your music, and how to win the loudness war in 2021 and beyond.

How loud should my album be in 2022? – Here’s The Short Answer:

Your master should be finished to the volume it sounds best at to you, with consideration to what’s expected by the average listener for the genre. That is the sweet-spot.

You were expecting a measureable number? I’ll get to that, but there’s more to what’s the best mastering volume than one easy answer. I’ll tell you what is not the right approach:

It is NOT wilfully hitting a streaming platform’s published targets without a second thought for what’s right for the genre (more on this later).

It is NOT trying to get the loudest master just for the sake of it (or to “beat” your mate’s track), sacrificing dynamic range and punch in the process (never confuse volume with punch).

These days it’s best to go for what works best for your album, not try and fit in to other people’s shoes. This is not a “wooly” answer – there is no single right dB or LUFS answer. I’ll explain further…

(If you really need numbers now, skip to the “What’s the best LUFS for mastering?” section below.)

Playback Methods Have Changed

These days people consume music in more ways than ever before. From beautiful full-range systems to terrible speakers built into a phone. The playback medium matters too – if music is streamed from the internet, played from a CD, hard drive, vinyl or even old-skool cassette tapes which are now a “thing” again – all the formats have subtly different ways of handling the dynamic range, tone and volume of music.

The best mastering has to sound great on all these devices – that’s one of the biggest challenges for a professional mastering engineer.

A major part of this, and a long-running debate among record labels, producers and all the best mixing and mastering services is “How loud should my master be?“.

You have probably heard the term “the loudness war” – the unofficial battle between record labels asking mastering engineers to push the intrinsic volume of records to the maximum – trying to be the loudest track on every mixtape, and a louder CD than the previous.

This has been a hotly debated topic since the mid-90’s. One camp likes the more compressed, slammed, thicker, heavier finish – but at a cost of dynamic expression.

The other side prefers the more dynamic, bouncy, open, vibrant finish – but at the expense of aggressive volume.

This all got really silly in the early-mid 2000’s, with many album casualties being pushed so much they were transformed into worse versions of their original mixes due to over-agressive limiters being pushed way too hard.

Even naturally heavier genres like hip-hop, rock and dance music suffered casualties in the loudness war. Often the worst atrocities being committed by the biggest bands (Metallica “Death Magnetic” is probably the most famous, with legendary mastering engineer Ted Jensen actually distancing himself from the end result).

Most music will lose power and be made to sound weaker by pushing the intrinsic volume ever-higher. This sounds counter-intuitive, but is true. Without dynamic range there is no punch. Volume without punch is just noise – just annoying. You can always push louder – but there will always be a cutoff point where pushing louder is no longer an improvement.

Of course, different genres of music differ in their requirements. Mastering dance music will generally need a lot more heft than mastering jazz music or mastering ambient music for example. One of the reasons the loudness wars became such a problem was that many mastering engineers were applying far too heavy compression and limiting to softer material, killing the dynamics and making it sound crushed and lifeless – totally unnatural for the genre.

Cue listener comments like “the mastering is too loud”.

Often, I’m sure this was at the insistence of the client, not the mastering engineer’s decision (as a professional mastering engineer we can advise, but the customer always has the final say).

I often have new clients approach me with poor-quality masters done online by an automated service. Often some of the issues come from the track being too pushed, or not enough (usually too much). Setting the best mastering level for music relies on more than just numbers. AI is getting better all the time, but you still need a human for the subtle bits.

So how do you know what loudness is right for your music?

Before We Proceed – The Simplest Explanation of LUFS on the internet!

What are LUFS? Jargon-busting answer:

When artists ask “How loud should my master be”, what they probably mean (technically speaking) is “What LUFS should my master be?”

What are LUFS? = LUFS stands for Loudness Units relative to Full Scale (or just “Loudness Units/LU”). They are a way of measuring the intrinsic volume of a piece of audio, relative to 0dB – which is the absolute loudest signal possible in digital audio – in the same way that a cup can only ever be filled up to 100% full, and no more.

A cup with 100ml capacity can only ever hold a maximum of 100ml of water, if you try to add more than 100ml the excess just spills out, losing water. The same theory holds in digital audio – an audio file can only ever have its volume filled up to the maximum, and you can’t go beyond the finite limits without losing data (as if it spills out over the edge).

In digital audio, some key knowledge is that 0dB (Zero dB) is NOT silence, it is actually the loudest you can go. 0dB is our “full” loudest point, and going quieter is measured in minus numbers (so -25dB is actually quieter than -3dB).

Now we’ve got these basics out of the way, what do LUFS do and how are LUFS used?

Practically speaking, a LUFS measurement tells you the perceived loudness of a piece of music across a sustained measure of time, and this LUFS measurement is the most accurate reflection of how “fat”, “full” or “hefty” the track will sound to the listener, compared to similar tracks, when played through the same Soundsystem, at the same volume.

LUFS are also very similar to the more famous dB/decibel. Actually, in practical terms 1dB is the same amount as 1LU. So if you lower the volume of something by -3LUFS, you could also say you reduced it by -3dB.

So what’s the difference between dB and LUFS? Both LUFS and dB can be used to express a measurement of difference between 2 things e.g. “take the vocals down -2dB from where they are now“, or a fixed volume reference (e.g. “the neighbours registered a noise complaint of 80dB”.

The most important dB vs LUFS difference from a professional audio work perspective is that the dB scale represents how much air pressure a sound will produce over a very short time, and needs to be referenced to another point (which is standard air pressure) to get a measurement.

In contrast, LUFS is a unit of measurement measured from within the audio, relative to the loudest it could possibly be, and measured over a longer time.

So the LUFS measurement is more similar to measuring how much water we have in our cup with 100ml capacity. LUFS is measured backwards from full-scale (full capacity), so using our 100ml cup analogy again, if we had 90ml of water in the cup, you could also say you had the capacity of 10ml left, or -10ml to full capacity. If you only measured backwards to 0ml capacity left (a full cup), then if you had 60ml water in there, the spare capacity measurement would be -40ml.

Same idea for digital audio measurement: digital audio can only ever go to a maximum point before clipping (the cup overflowing), which is always referenced at 0dB (our full capacity). Both dB and LUFS are measured like this. So a measurement of -5dB means you can raise the volume up another 5dB before the audio clips and data gets lost (the cup runneth over). A measurement of -10LUFS means there’s a limit of another 10LUFS before the audio is the loudest it could ever possibly be (the full cup again).

But dB is measured only in comparison to another part of the setup. To invent a random example: your bass guitar is at full volume, and has -3dB headroom going into AMP #1 before distortion. But if you patch it into amp #2 it may have -8dB headroom, because the amps are built differently. So the measurements are accurate, but not as translatable.

Whereas LUFS for mastering is measured from within the audio file, using 0dBFS (full scale, or the loudest it could possibly go: our full cup analogy again).

LUFS could be viewed as a more modern, improved version of RMS which gives an average volume of audio. I’m going to say it – nobody really uses RMS much in mastering standards these days (apart from a few stragglers), so I won’t bother going into RMS beyond this mention. Use LUFS instead.

Measuring audio using LUFS gives a more accurate picture of the track volume over a longer time (often the entire track is measured and represented, sometimes just key anchor point sections). LUFS are the best unit we have to measure audio loudness in 2021 but it’s still not “perfect”. You still need a pair of experienced, human ears to translate this stuff beyond the numbers.

If you mastered an album of reasonably varied tracks all to a rigidly set LUFS level, without using your ears for a final check to see if it sounds right, you would probably find the album isn’t as cohesive as it could be.

LUFS are really useful, but your ears are still needed for a final check in the real world, as so many other factors come in to play, like tempo, instrumentation, vocal styles across the album etc.

For example, it’s very common for a track to have a radio mix + an extended mix. Chances are both these tracks will have different LUFS readings – because if the extended mix has a longer intro, longer breakdown and longer ending, the LUFS measurement will take ALL the audio into account, and so the extended mix will probably have a lower LUFS reading than the more concise radio mix….. which will lead to Spotify + other systems that use an automatic volume-levelling system to adjust and then play the two mixes with different volumes.

Also massively important is If the initial anchor point of the album is not chosen correctly, the entire foundation of the album may not be optimised. This is another factor where a human brain will always beat AI – because it hinges on an emotional response.

What’s the difference between Peak Level and True Peak?

The Peak Level of audio is another separate measurement of how loud your track is, and combined with LUFS gives a realistic picture of how your track will compare in the real world. Peak Level is measured in dB, and it’s how loud the loudest single peak of your track is, relative to 0dB (the absolute loudest it could possibly be in digital audio – the full cup). This is slightly different to how LUFS is used, but they work hand-in-hand.

Although LUFS and Peak are both measured relative to 0dB (how much capacity is left available to fill), Peak level sounds different overall to a LUFS measurement, because Peak Level is only measured at the one loudest point of the WAV, which can be a super-short sound (like 1 loud snare hit), rather than LUFS which measures the overall loudness of the track over a longer time.

Imagine recording an instrument with -7dB headroom, then suddenly someone slams a door taking the recording level momentarily up to -0.1dB. The bang is 6.9dB louder than the instrument, but the recording never clips (0.1dB peak headroom left before clipping).

This recording would technically be -0.1dB Peak Level: almost as loud as possible before digital distortion, but when you listened to the audio it would still sound quiet until the door slam – because the door slam is the loudest bit. So the Peak Level on its own doesn’t give an accurate real-world indication of how a listener would perceive your audio.

A LUFS measurement of the same audio would show a more accurate real-world result of somewhere around -6.4 to -6.9LUFS (depending on various factors including how long the measurement was): this measurement more accurately reflects the overall quiet nature of the audio file in the way our ears would perceive it.

The LUFS measurement would not ignore the big hit of the door slamming, but that 1 big hit wouldn’t massively skew the entire measurement like it would for a dB measurement.

So what’s the difference between Peak and True Peak?

Digital audio is very accurate these days, but it’s not bulletproof. Sample rate is how many times the audio waveform is measured (or “sampled”) per second. So a sample rate of 96kHz samples the waveform 96,000 times every second. Sometimes the point where the audio is sampled happens either side of a waveform peak, so the recording misses the exact level of the peak.

Imagine if you were watching someone throwing and catching a ball outside your window. You could see the ups and downs of the ball, but then if it was thrown higher above your window view, you would miss seeing exactly how high it went – because it went beyond your maximum vision. If the top of the window frame represents 0dB (the loudest we can measure) the actual height the ball reached, out of your vision, represents the true peak.

So bizarrely, audio that is badly clipped can actually have a positive True Peak of +dB. Which is only ever a bad thing, and not actually part of the sound – more of a measure of how much signal has been lost, but still taken into account by streaming platforms to avoid the possibility of clipping at the consumer end. This contradicts what I said earlier about digital audio being unable to go beyond the 0dB level, but understand a positive +dB True Peak measurement is not the same as proper audio. It is a measurement of how much data has been lost at that point.

Masters that have been pushed hard and finished to -0.1dB (the old standard), without a special limiter that deals with intersample peaks, can have True Peak measurements of +4dB or more – a major issue for streaming platforms, as you will read.

That’s the simplest explanation of LUFS, Peak and True Peak without getting into the technical jargon I promised I’d avoid.

What’s The Best LUFS For Mastering?

Most streaming platform guidelines state an ideal Loudness of around -14LUFS, but… I KNOW CATEGORICALLY FROM EXPERIENCE that if I deliver a dance/electronic/hard rock/hip-hop/breakbeat/punk/D&B track to a client finished at -14LUFS, they will INEVITABLY ask for it to be pushed harder! 99% of the time. Even if I explain the theory, they ask for it to be pushed louder anyway. Make of this what you will, but that’s the reality of mastering records professionally for other people, and hence the reality of how most released records are finished in the real world. More on this later…

The “correct” mastering volume is never a one-size-fits-all approach, but if you really want numbers (of course you do), I often find somewhere around -9LUFS to -11LUFS to be the sweet-spot for many styles of electronic and rock music.

For mellower material, I often finish somewhere around -12LUFS to -14LUFS.

However, depending on the intentions of the artist, and bearing the genre in mind, I will finish anywhere between a blistering -5LUFS (for insanely fat “pushed” sounding dance music – that’s TOO pushed in my opinion!) to -15LUFS (for gentle ambience).

In a nutshell I deliver what the client wants. I have a couple of clients who are quite big names, that I know to deliver at around -5 or -6LUFS because that’s what they want. Personally I don’t agree with that approach, but I’ve had the discussion & that’s what they want. Their music racks up millions of Spotify streams, so it would be wrong of me to consider them “wrong”. Food for thought.

Note: these measurements are for music designed for playback by consumer – I.E. record releases. Different, very specific standards exist for broadcast TV and mastering audio books etc. (but that’s for another article). Here we’re just talking records which have no rigid standards we must adhere to.

So, what LUFS is correct for mastering in 2022? = Whatever works best for your album or song and gives just the right amount of weight, bounce, bump n’ grind, the break point where joy happens for you. Whatever finish you feel represents your music and what you are trying to achieve – that’s the ideal mastering LUFS target in 2022.

“Hang on a minute buster! I thought Spotify/Apple/Youtube said you HAD to finish your masters at precisely -14LUFS, or they’ll kick your butt! What gives, Chum?“

Settle down, imaginary sceptic, I’ll explain:

What’s The Best Mastering Level For Streaming?

In 2021 music streaming services rule. The CD format is becoming rarer every year, and although there will always be vinyl fans (me included), it’s no longer a common commercial format for most artists. So it obviously makes sense to master with the main method of music consumption in mind.

Most streaming platforms like Spotify, Soundcloud etc. now have “normalising” (automatic volume levelling) built-in. This a great for the listener, because if you are listening on shuffle mode and an industrial rock track comes on after a mellow blues song you won’t suddenly be hit with a louder volume and have to rush to turn down the volume control.

There are a couple of different volume leveling systems being used, but the general idea is that they analyze the tracks intrinsic volume in LUFS, before adjusting the playback volume to compensate, thus leveling out the listening experience.

Many streaming platforms like Spotify, Tidal etc. state an “ideal” mastering level of -14LUFS, with True Peak of -1dB.

A track of -10LUFS, True peak of -1dB would have the Spotify playback volume turned down -4LUFS to match their standards of -14LUFS playback volume. A track with less headroom than -1dB causes a further playback volume reduction to compensate too, as it will adjust until the song also plays back at -1dB True Peak.

This “turning the volume down” is also known as the “Spotify Loudness Penalty”. More on that later, and why it’s less scary than it sounds.

You would think if you set your mastering output to -14LUFS with True Peak of -1dB then it’s already totally nailed, right? Sometimes, yes absolutely. But in the real world nothing is ever that simple, and if you follow that idea for every track or album, then you may not get the results you want in the end.

Most electronic, urban and rock music sounds a little weak and thin at -14LUFS, compared to the majority of records in their genre. For example, if you mastered a house, electronica, heavy rock, drum n’ bastype of track at -14LUFS, it will sound pretty lame compared a similar track that was finished at -10LUFS.

Understand that the -14LUFS track doesn’t just play back -4LUFS quieter, but SOUNDS less “full”, less “finished”, less “ballsy”, less “fat”…. you get the picture.

When I first learned about digital streaming targets a while ago, I started mastering music finished for those specs. Every electronic, dance, heavy rock or trailer music track I finished to -14LUFS got the same response from clients: “It sounds great, but can you squeeze a few more dB out of it?”. I explained about the targets, but they wanted more “ooomph”. In seriousness, I actually agreed.

So for these heavier genres of music I stopped finishing them to an arbitrary number, and went with my gut and ears again instead – no more volume boost requests from clients.

Don’t get me wrong, I definitely think some forms of music definitely sound better around -14LUFS. Mellow acoustic music, singer songwriter, some orchestral, lighter reggae, light jazz, piano music and several other genres will certainly not benefit from being too “pushed”, and a -14LUFS finish may be appropriate.

Sometimes genres blur, certain sounds or instruments will lead the focus, perhaps it’s a drum-heavy track, or there are no drums at all, just an ambient drone. What if there is an album full of variation?

With so many variables, how do you decide what LUFS to finish at? This is where an experienced professional mastering engineer will make the call, and find the best finish for your track or album. Confidence, knowledge and an instant understanding of what is “right” which comes from years worth of experience.

For example I estimate I have completed around 39,000 hours of studio time (30 hrs per week average over 25 years, since getting really in to music production aged 16 in 1996. Probably more hours as I used to pull a lot of all-nighters in my youth).

The Problem With Only Using Numbers To Set Your Mastering Loudness

So much more needs to be taken into account than just aiming for a measurement. The tempo, orchestration, how it was recorded, the intended audience, the intended playback settings, the customs within each genre and the spectral and dynamic balance compared to other tracks on the same album should all have a part to play in the final loudness decisions. There’s no meter yet that can measure all those things as accurately as a trained human brain.

The various different streaming platforms are still refining their auto-volume leveling systems, and there is still a lot of debate over what is the best method to use, and ideal target too. These published streaming LUFS targets should be viewed as moving goalposts, and a guideline, not an unbreakable rule. They could change next year!

So, let’s take Spotify mastering LUFS standards for example. They state – 14LUFS as the ideal mastering level. So a -14LUFS master will essentially bypass the auto-volume leveling system and have no adjustment in playback volume when played on Spotify.

If you analyze your favourite dance, hip-hop or rock tracks (even new releases on major labels), I’ll bet you will struggle to find many that are actually finished to -14LUFS. I suspect you’ll find numbers more in the range of -12 to -8LUFS, maybe even down to -6LUFS : a long way off the published “ideal” -14LUFS streaming targets. Why is this? Surely if streaming is king, we must all follow their demands?

These real-world standards are partly due to 20+ years of the loudness wars, but also because some styles of music just sound “better” when they have been pushed a little harder. We as listeners have come to expect that full-fat, hefty sound from some genres, and often that needs a slightly higher LUFS master.

But that’s where auto-volume-leveling come in, right? Won’t Spotify iron out all these differences and make everything sound the same level anyway? So if you master to -14LUFS it will sound better than a track mastered at -11LUFS, won’t it? Sort of, but it’s more complex than just numbers.

In a real listening situation the listener’s perceived loudness of a track is very heavily weighted on on other factors beyond just LUFS and dB. The instrumentation, treble energy, punch of the bass, timbre, vocal performance (or if it’s an instrumental track) and the mixing style are all variables that combine to change how the listener perceives the track. Plus the listening environment itself has a major bearing beyond just a LUFS measurement.

Example: If you play 2 heavy electronica tracks back to back. Track A is finished to -9LUFS, track B is finished at -14LUFS. Let’s say you turn up the playback volume for track B by +5dB, to compensate for the mastering differences, so in theory, both tracks should sound the same volume…. What happens? Track A will still sound “fatter” to the listener, even though the playback level is technically the same. This is because there’s more power within the track itself, it’s “stronger” than the -14LUFS alternative.

Other camps will argue that the dynamics will be punchier in the -14LUFS master Vs. the -9LUFS master at the same perceived volume, and that is true… but dynamics punchiness is only one factor, and isn’t always the most important factor to consider for some music genres.

The lines can be blurred about what is “more important” in a track – dynamics or weight. This is key.

For some music, open punchy dynamics easily sounds best. Sometimes you want that “pushed” hefty feeling and sacrificing some dynamic range is a better option. It’s all to play for, and anyone who clings to one rule for all is missing the point – the mastering approach should be fluid, and optimised for the individual aesthetic required.

This is the indefinable sweet-spot of which I speak. This is the magic feeling we must capture in our master. What is right for the track, or album in a wider context. An AI online mastering service can’t define this – AI has never been raving, never crowd-surfed, never excitedly hugged its mates in a sweaty heap at a gig…. you get the idea. There’s more to enjoing and understanding music than numbers.

If 2 hypothetical heavy electronica tracks were played back-to-back on Spotify, the underlying volume of music in the room would be nice and level, but track A (-9LUFS) might well sound fatter and fuller than track B (-14LUFS). Probably NOT the artist’s intention for track B, aiming to sound fat!

Also, streaming services will turn audio down based on Peak Level, but currently they won’t turn it UP (remember this may change if/when they change systems)! So if you master a track to -14LUFS, and leave -2dB True Peak (as is preferred by some platforms), then it would sound -1dB quieter again than a track finished at -14LUFS with a TP of -1dB when played back on some platforms that prefer a TP of -1dB..

This volume-leveling can backfire in a more extreme way when faced with extremely dynamic material, like orchestral music which can have a long build of quiet followed by a few scattered big hits, which will actually then be affected by a built-in limiter on streaming systems to protect against unexpected clips like in this example – what are the chances that the arbitrary limiter response will fit your music musically? Hmm.

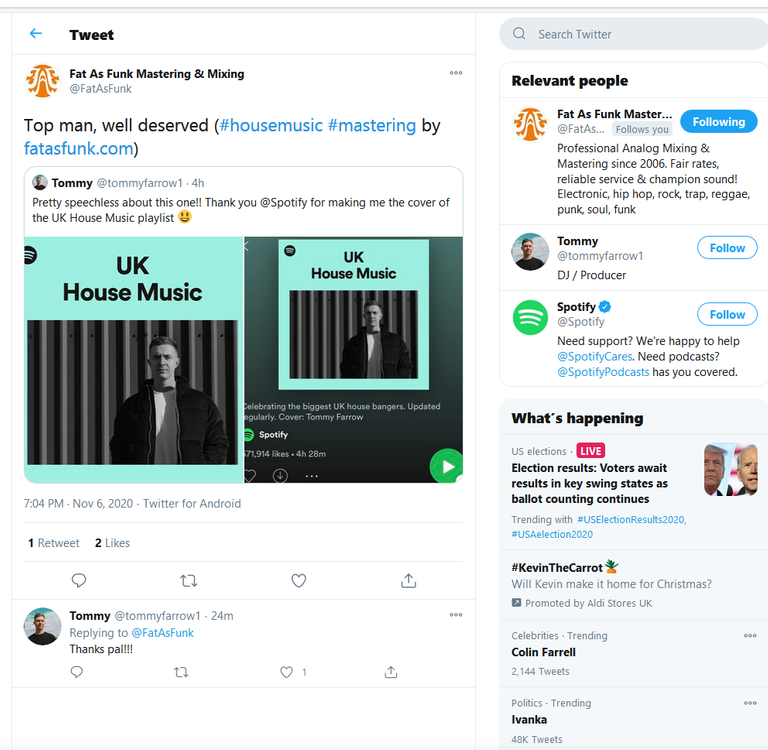

The recent house banger “Let’s Just” by Tommy Farrow (Stress Records) hits around -7LUFS in the chorus, sounds fat, loud, lovely and is a massive hit. But -7LUFS is a lot louder than Spotify’s preferred -14LUFS. Will that make it less favourable to Spotify’s algorithms? No, as he has made the front cover of the Spotify House Music playlist.

Likewise look at the runaway success of the Lau.Ra tracks Wicked & Don’t Waste My Time (Needwant). Both of these have been dominating the electronica charts, are all over a load of Spotify playlists, and are finished at a meaty -4.8LUFS: almost 10LUFS louder than the official Spotify guidelines (this extreme level was at the artist’s request by the way, but I do agree it sounds dope in this instance).

I’m not saying this super-pushed finish is the right approach all the time, but it does prove that the Spotify “Loudness Penalty” we touched upon earlier doesn’t penalise discoverability, which is an important distinction to make. If a producer is racking up millions pf plays, who's to say their choice is "wrong".

I’m usually against pushing a track to these extreme LUFS levels unless the artist requests it or it really suits the track. But it proves anything can be possible and still get a great result if done well.

Dynamic, bouncy and open Vs. Tight, fat and solid. A good mastering engineer will advise, but at the end of the day the customer needs to be happy first, so we will always enable the artist’s vision, and at the end of the day, the customer is always right.

Official Loudness Targets For Different Streaming Platforms

In the interests of giving you complete information, here are the suggested levels given by the platforms when mastering for streaming. If you’ve read the article above you’ll understand there are more factors at play in the real world. Many softer sounding genres will sound great at these levels, so as previously said - do what sounds right to you. Here they are anyway:

| Service | LUFS | True Peak |

|---|---|---|

| Apple Music | -13 to -15LUFS | -1 dBTP |

| Amazon Music | -9 to -13 LUFS | -2dBTP |

| CD | No “official” standard | -0.1dB |

| Club Soundsystem | Can be up to -6LUFS | -0.1dB |

| Deezer | -14 to -16LUFS | -1dBTP |

| Soundcloud | -8 to -13LUFS | -1dBTP |

| Spotify | -14LUFS | -1dBTP |

| Spotify Loud | -11LUFS | -2dBTP |

| Youtube | -14LUFS | -1dBTP |

Published streaming loudness “targets”. Accurate as of 2021. Subject to change.

How To "Win" The Loudness War In 2022 And Beyond

Looking at the long term picture, it seems important not to base your mastering decisions entirely on arbitrary number targets decided by streaming platforms (which are not totally agreed on yet, and will probably change several more times over the years).

It also seems like a bad idea to push for insanely loud LUFS for the sake of it when it’s generally agreed that auto-volume leveling is a good thing, and will only get better as it advances.

Shouldn’t we still fight in the loudness wars? = Not any more (if you ever should have in the first place). Pushing your mastering too hard for the sake of winning the mythical “loudness wars” has been proven many times over to be an exercise in futility, and will ruin the dynamic detail of your track for a “quick hit” of volume. The loudness wars were also from a time when people bought a physical CD – when did you last buy a CD?

Nowadays with automated volume-leveling becoming more common in both playback systems and streaming services, it is less important than ever to try and be the loudest on the block. Also, don’t forget that every music playback system in the world has a volume control (and it’s usually the biggest dial right in the middle too).

Why permanently set your album masters for an outdated competition, for an outdated format, which was a bad idea in the first place? Or for a digital playback service that will probably change their standards several more times in the next few years.

All things considered, it’s often not the best idea to finish your master based on only the LUFS measurement given by a streaming service either, without giving priority to what’s best for the music, and the confidence to know what works best for the individual album.

It’s not usually the best approach to push your record beyond its sweet-spot just to be “louder than track (x)”.

Modern mastering standards allow you to let go of some worries:

Don’t worry about pushing it crazy-loud for the sake of competing in a phony war and sacrificing your dynamic range.

Don’t worry if your music slightly exceeds the suggested Spotify loudness targets, it will still sound awesome.

Don’t worry that your mate did a DIY home-master using headphones and free plugins that’s louder than anything you heard before… and louder automatically means better, right? (wrong).

Remember the old mastering engineers saying “it’s not how loud you make it, but how you make it loud”. Very true.

In a nutshell – the BEST mastering volume target for 2022 & beyond is what sounds best for your record based on what you want to achieve artistically.

We are happy to advise you which route to go beforehand, or explain our decisions afterwards.

At Fat As Funk we always mix and master for the level that suits your music best, and will always make sure you love your final masters 100% – whatever the final LUFS!

With remote working now the accepted ideal, it’s no longer important to only think about “mixing and mastering services near me”, we have clients across the globe.

Upload your track to Fat As Funk now and try our mastering for free!

I hope you have found this article informative without being TOO boring haha. If you have read it all, then congratulations! You are a true audio fanatic. Big loves, Loz x

Congratulations @fatasfunk! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s):

Your next target is to reach 2250 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCheck out the last post from @hivebuzz:

Support the HiveBuzz project. Vote for our proposal!