One of the many things that set us apart from the other living beings is our habit of keeping records, usually written, of our own history. Our species is quite unique in this regard, while it is true that the rings on tree trunks serve as a kind of documentation of the life of that particular tree, we are the only ones who purposely describe our past. However, as imperfect beings that we are, many times these files have defects such as insufficient information, erroneous interpretations of the events that occurred, or directly falsehoods that can be taken as real events after centuries or millennia. For this reason, it is always necessary to corroborate any historical evidence by reviewing various sources, although this is not always possible.

But this is not the only problem. We must remember that any historical event will always be described through the prism of the past, with all the ignorance and retrograde thought that this may entail. Things that once seemed like magic now have an easy and reasonable explanation, and thanks to all the current advances we are able to reconstruct events from millennia ago as if they were happening right now. Of course, this is not always possible, no matter how hard we try (and fortunately so for this series of articles); There are events that, although well described, are difficult to explain even today, either because even in the middle of 2020 we do not have the tools to do so, or simply because it was something unique that has not yet been repeated, and perhaps never will. Today I bring you one of these events about which there are still questions that have not been fully answered: the **English Sweat epidemic **.

Medical Mysteries: The English Sweat

It was the year 1485 in medieval England and the War of the Roses had just ended, leaving Henry VII on the throne as the first monarch of the House of Tudor who would rule for almost 120 years. For ordinary people far away from the royal court, life remained pretty much the same, however: a grueling existence of working countless hours a day to put bread on the table, with few distractions, and a life expectancy of just over 40 years due to diseases for which the only cure was to pray a lot and hope for the best (or, more frequently, until death), and frequent wars for the benefit of their rulers. And if this wasn't enough, their life was about to get much worse before it got better.

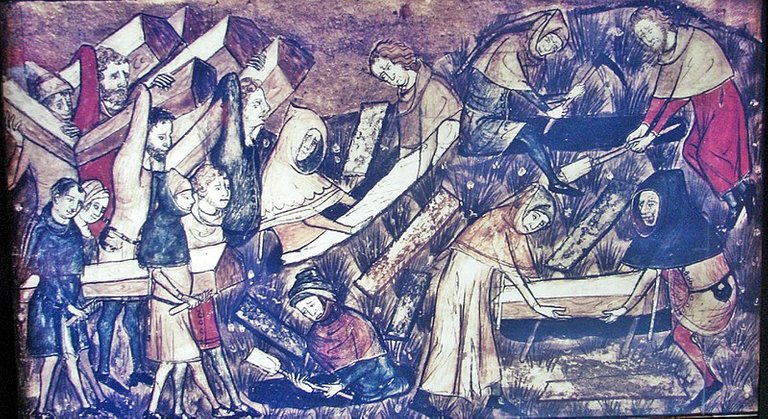

You see, Henry VII's troops would bring back something other than victory; the then still claimant to the throne, and not a particularly big believer in things like "fair play", had reinforced his army with French mercenary troops, who brought a new epidemic to English lands, apparently imported from Normandy and Rouen. In England, this new pathogen found the same perfect environment for the spread of diseases that the Black Death had been taking advantage of for a couple of centuries to annihilate a good percentage of the European population: a personal hygiene that basically consisted of "bathe at least once a year and try not to shit on the table, if you can avoid it", overcrowding that could be extreme in poor households, almost total ignorance about the nature and spread of diseases, and the lack of sewers, aqueducts and sanitary services in narrow streets that turned into sewers for both animals and people. Thus, to this cocktail of filth and general uncleanliness that would overshadow any public bathroom in any service station in the current world would arrive a new cause of death, apart from the aforementioned Black Death, typhus, measles, smallpox, syphilis, and dysentery (I could go on, but you get the point. The current pandemic doesn't seem so bad anymore, right?).

Although, looking at the bright side of things, all of that made possible the creation of the coolest doctor outfit ever, so there’s that.

The first outbreaks occurred on September 19, and by October it had already killed 15,000 people, including the Mayor of London, his successor, six councilors, and three sheriffs. Its epidemiological behavior was extremely strange, since it did not affect infants or young children, and it was not very frequent among the lower class, who normally suffered the worst part of any epidemic; It mainly targeted young adults, wealthy or upper middle class, focusing almost solely on England and its provinces, being almost unheard of in Scotland or Ireland, let alone the rest of Europe. It is even said that no foreigners residing in England were infected, although there are no reliable sources to corroborate it.

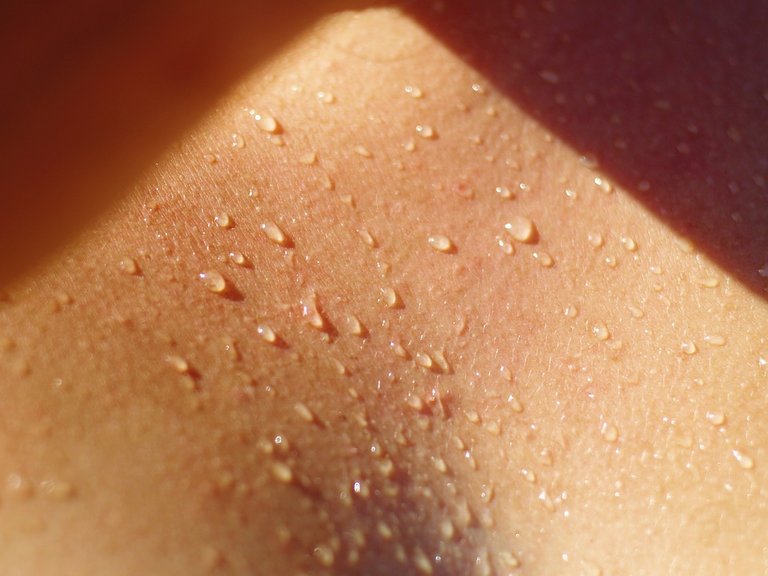

The disease had an incredible mortality (the historian of the king's court estimated it to be 99%) and the only thing that prevented it from ending with a huge part of the population was that those who suffered it died so quickly that they could not transmit it to almost no one else. A manuscript published in 1490 by a French physician named Thomas Le Forestier described its symptoms, explaining that there was "profuse and foul sweating, flushing of the face and all over the body, much thirst, high fever, and headache, and sometimes black spots on the skin”. This characteristic sweating gave it the name of English Sweat, or sweat anglicus, because everything sounds better in Latin. In addition to these clinical manifestations, some patients also presented violent chills, pain throughout the body, general asthenia (weakness) that could be incapacitating, and in its later stages, great drowsiness to which many succumbed, never to wake up. Its fatality was such that some died suddenly on the street while walking, in periods of time as short as just 6 hours after symptoms began. However, if they managed to survive the first 24 hours, they generally recovered, though there was a possibility of reinfection since its contagion did not generate subsequent immunity.

But the autumn of 1485 was not the only time this disease occurred; there was a second outbreak between July and August 1508 in which the Royal Court even had to leave London and issue a decree prohibiting the contact of ordinary people with them, a third episode occurred between July and September 1517 leaving more than 10,000 dead and in which the victims were said to be "merry at lunch, dead at dinner", between June and August 1528 there was a fourth epidemic that for the first time crossed English borders and spread widely in Europe, affecting Germany, Prussia, Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland and other countries. Finally, it attacked England again from April to July 1551, beginning with Shrewsbury County instead of London, and then disappearing as suddenly as it had begun.

But what exactly was the English Sweat? Was it of viral origin, or perhaps transmitted by an insect such as the Black Death? Can it re-emerge one day? Well, as much as medical science wants to answer all these questions (especially the last one, we don't exactly need another pandemic), the truth is that it is quite difficult. We were able to identify the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which caused the Black Death, because it survived to the current age (and some sporadic cases still occur even today), but since no cases of English Sweat were documented after 1551, and due to it having several similarities with so many other illnesses (albeit being much more deadly and rapidly evolving), along with poorly detailed chronicles that basically blamed "foul vapors" or some sort of supernatural curse for the spread of this disease, it's challenging to identify its true cause. Let's try.

During the latest epidemic, Royal Court physician John Caius identified a host of characteristic symptoms: poorly focused pain, heart palpitations, lethargy, drowsiness, and altered mental status. Several of these manifestations were shared by a very similar pathology, the Picardy Sweat, guilty of 194 epidemics in France between the years 1718 to 1874, however, in those affected by this disease there was always a papules-vesicular rash of approximately one week in duration which was not always present in the English Sweat, moreover, its lethality was notably lower; between 4% to 50%. Justus Friedrich Karl Hecker, German physician and bearer of a name which is impossible to say without sounding angry (like most things in German) stated in his book The Epidemics of the Middle Ages that the English Sweat was an "inflammatory rheumatic fever with a great nervous system disorder ”, while the Picardy Sweat was “undoubtedly a miliary fever” and much less malignant.

The Sudor anglicus can also be compared to morbus cardiacus, a condition endemic in Asia around 300 B.C. and which was said to cause excruciating sweating, but it had symptoms that differed even more than Picardy Sweat’s; without rheumatic manifestations, and occurring at different times of the year and weather conditions. Another possible explanation for this disease could be an infection by some type of hantavirus; a family of viruses that normally reside in mice and other rodents asymptomatically and are transmitted to humans through fleas. In 1993 an outbreak occurred among the Navajo of New Mexico, United States, named the Four Corners Outbreak because of its geographical location, caused by a type of hantavirus called Virus Sin Nombre (or “Nameless Virus” in Spanish. Yes, that's the official name) which had some manifestations in common with the English Sweat, but again, there were also differences: different lethality, respiratory and hemorrhagic symptoms absent in the English pathology, and the fact that hantaviruses are not normally transmitted from person to person, something practically necessary to explain the rapid spread of sudor anglicus.

There are several other hypotheses about this condition, such as that it was some variant of influenza, scarlet fever, typhus, or enterovirus, but none fully matches with the descriptions of the English Sweat. However, the problem with this is that the records varied according to the author: I previously mentioned that the historian of Henry VII’s Court estimated the lethality at 99%, but the truth is that other chronicles contradict this. For example, during the epidemic of 1529, 4000 cases were registered in the German city of Stuttgart, leaving only 6 dead, that is, a death rate of 0.15%. It is evident that with such different accounts it is almost impossible to reach a solid conclusion, and this is precisely the reason why there are so many speculations, and just as it is difficult to choose one as the definitive explanation, it is also hard to discard them all.

Do we have an unsolvable mystery before us, then? Well, while it is impossible to clarify all the questions that this condition leaves us with absolute certainty, we can theorize using what we know and formulate a reasonable answer. An important fact is the predilection of the disease for men with good economic conditions, and one of the many things that these individuals had, and the rest of the population did not, were large households that required a good amount of maintenance personnel, and therefore, ample food reserves. And with so much food accumulation, it was almost inevitable that along with the human tenants, an enormous plague of rats and mice would move, full of possible pathogens. The cause of the English Sweat, then, almost certainly was some type of virus (possibly a hantavirus) or bacteria that used these animals as a vector, whose final host was human, and being capable of transmission from person to person.

It is possible that the sudden disappearance of this disease was due to a mutation of its causal pathogen to a less virulent form, perhaps eventually becoming what later became Picardy Sweat, or maybe even becoming symptomatic and fatal to rodents that originally transported it, killing them before they could infect humans. But again, we will most likely never know for sure what caused the English Sweat epidemics and why no more cases were documented after 1551. Taking into account the fact that the only way to clarify our doubts is to resurface a new outbreak and we can study the pathogen with the current tools, perhaps this is for the best, but I would like to end this article remembering that without knowing how it started, there will always be the possibility that someday a number of people will start to sweat profusely, whether in England or anywhere else, and then drop dead within a few hours, and we will have a new crisis on our hands. I do not want to sound negative, much less spread panic, but the year 2020 has already brought us many surprises, I think that at this point nothing should surprise us anymore. Have a good day!

References:

- Concerning the enigmatic English sweating disease07932010000400012)

- Sweating sickness and Picardy sweat

- Wikipedia – Sweating sickness

- Encyclopedia Britannica – Seating sickness

- The Pharmaceutical Journal – Just what was the English sweating sickness

- The Conversation – What was sweating sickness – the mysterious Tudor plague of Wolf Hall?

- CDC – Tracking a Mystery Disease: The Detailed Story of Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS)

- Wikipedia – Sin Nombre Orthohantavirus

This is a very good write-up, @mike961. I really enjoyed reading it. Thanks.

Thank you so much, I'm glad you liked it!

this absolutely well researched and present. Understanding the mystery behind certain phenomenon in nature can be quite talking. you made a good effort to bring this to our knowledge. i definitely learnt something new today! however, you may want to edit the footnotes for your images so things look a bit more tidy around there. Cheers!

Thank you, it always makes me feel great when someone learns something new because of my posts!

And yeah, I seem to have a problem with the footnote of an image, I think it's due to the file name since I can't link the source page, though I also can't use italics, idk why. Best I could do was leave it like it is now, I hope it looks good enough.

Oh ok.. it's no problem. You did great brother!

Thanks for your contribution to the STEMsocial community. Feel free to join us on discord to get to know the rest of us!

Please consider supporting our funding proposal, approving our witness (@stem.witness) or delegating to the @stemsocial account (for some ROI).

Please consider using the STEMsocial app

app and including @stemsocial as a beneficiary to get a stronger support.

Hey @mike961,

thank you for the article.

Concerning:

We don't sound angry, just a bit angular.

Concerning the article: It would be nice to know whether this age- and gender-related pattern also occurred in the other outbreaks.

Best regards

Chapper

Angular could be another way to describe it, indeed lol.

I tried to look for more info on this but found very little, the sources from the rest of Europe mostly described the symptoms, and focused little on the epidemiology, though I did notice that in other countries it spread through a larger number of cities than in England, and in less industrialised ones, so it's safe to assume that the age and gender-related spread pattern probably was the same, but it most likely did not affect the higher class as much.

That does put a tiny dent in the hantavirus theory as an explanation for the outbreaks, but hey, maybe mice were less picky and/or more numerous in mainland Europe.

Phewwwww, quite a long read...

There is more to know and I'm happy that more articles have been dished out everyday in different dimension.

Hoping to read the next of yours

Thank you! I did find more information than I thought, not even I was expecting it to be so long lol. I hope it was interesting enough, though n_n

Congratulations @mike961! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

You can view your badges on your board And compare to others on the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPSupport the HiveBuzz project. Vote for our proposal!