“Aunty!,” an exhibit curated by Laylah Amatullah Barrayn and Catherine E. McKinley, reveals photography’s role as a tool or weapon when investigating identity and empowerment.

Uncovering the beauty of African women and their worlds within fractured and layered colonial histories demands a special attention to detail. As the documentary photographer Laylah Amatullah Barrayn and the author Catherine E. McKinley know, many of the earliest images weren’t meant to be seen as art. Yet they had a disturbing, global reach, fueled by the racism and voyeurism of unknown European photographers. And they trigger discomfort — if not outrage — to this day.

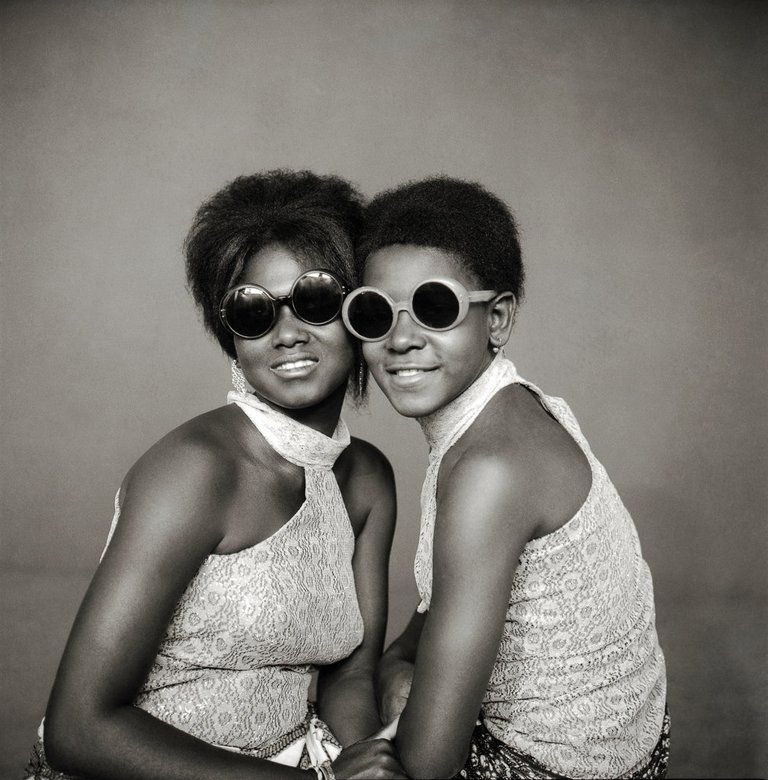

To counter uninformed portrayals of African women as servile or sexual figures, Ms. Barrayn and Ms. McKinley curated “Aunty! African Women in the Frame, 1870 to the Present,” an exhibition at United Photo Industries Gallery in Brooklyn that exalts their beauty on their own terms. Digging into history and offering a glimpse of a future narrative, the show features some 100 archival, vintage and contemporary photographs from the Catherine E. McKinley collection, a trove of photographic prints, cartes de visite and postcards spanning the African continent.

Ms. McKinley started collecting when she was researching the uses and evolution of indigo cloth from colonial to postcolonial periods. Studying images by Seydou Keita and the fashions his subjects wore, she delved deeper and researched textiles and trade history on a journey that took her to 11 African countries.

“I would go to people’s homes and they would let me look at their family albums,” she said. “They would have multiple images and wouldn’t mind giving me copies. Initially, I was intrigued by the social history around what they were wearing. I had a fixation with the images. Then, I started going online, looking for postcard dealers and antique shops.”

Ms. Barrayn and Ms. McKinley met at the Black Portraitures Conference in Paris in 2013, where they discovered they had an easy rapport and a shared interest in colonial and vintage photographs. Ms. Barrayn, who is based in Brooklyn, had been traveling extensively to Senegal documenting the Baye Fall Sufi community, and Ms. McKinley asked her to create photographs of some of the local fashions for her coming project, “The African Lookbook.” In Senegal, Ms. Barrayn pored over archives in Saint-Louis, visiting families and studio photographers who had colonial era images.

“I’m always interested in agency,” Ms. Barrayn said. “Colonial photographers used images for completely different intentions without the subject having any say in how the photograph was used. You can see the difference when a person in a photograph has agency. It’s in their posture and expression.”

Oluremi Onabanjo, a curator and scholar of photography and African art and former director of exhibitions at the Walther Collection, noted that the earliest images in the exhibition were historical documents from 1870.

“That’s less than 50 years after Louis Daguerre first presents the daguerreotype in Paris,” she said. “With these early images included alongside modern and contemporary works, you’re really getting a full sweep of time and a subversive perspective on how to investigate the history of photography, through its relation tied to black African women as subjects.”

Ms. Onabanjo feels the exhibit has a special timeliness, in subject and process, in showing the medium’s links to Africa. “It also hints at the future, where more women of African descent are placed as curators, conservators and historians of the archive,” she explained. “This is a groundswell moment, showing that the medium isn’t just for the ‘modern masters’ of documentary photography, but also is embedded in a larger geographical scope of circulation and production, of subjects and individuals. We can afford to have some room.”

Recent developments have been significant for African photography and contemporary art, and also for female artists of African descent. Christine Eyene became the first African woman to curate two biennales in the same year; the German-Cameroonian Marie-Ann Yemsi curated the 11th Bamako Encounters at the National Museum of Mali; and Sandrine Colard was appointed artistic director for next year’s Biennale of Lubumbashi in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Ms. Colard is also preparing the exhibition “The Way She Looks: A History of Female Gazes in African Portraiture” at the Ryerson Image Center in Toronto in collaboration with the Walther Collection.

“Doing the work of tracing agency and power relationships, acknowledging the place of black African women inside of these networks, is one of the largest honors one can do,” Ms. Onabanjo said.

“Aunty!” unites female subjects from colonial photos with those by the celebrated contemporary African photographers Seydou Keita, Malick Sidibé and James Barnor, highlighting post-independence partygoers, studio photography, vernacular images and contemporary renderings. Photos by Zina Saro-Wiwa (United Kingdom/Nigeria), Patricia Coffie (Ghana/United States), Fatoumata Diabate (Mali) and Thabiso Sekgala (Namibia) illuminate subjects who are African women and control their own image.

Mr. Sekgala’s portrait features a seated woman confidently wearing a Victorian dress. “There was a German-led genocide in Namibia in 1904 and 80 percent of the population was wiped out,” Ms. McKinley said. “The woman in the photograph is part of a committee demanding reparations. I love the image because it’s a Victorian dress, but the image expresses her resistance of the genocide.”

Ms. Barrayn, who is a co-author of “MFON: Women Photographers of the African Diaspora,” hopes the exhibit challenges viewers to contrast how photography was used then and now.

“We are talking about fetishizing the black woman’s body and the agency of studio photography,” she said. “We look at how colonial photographs were distributed around the world, without the subjects’ permission, through postcard correspondence. It’s important to see how powerful photography is in shaping how people think about black women and also how it can be used as a weapon or as a tool for empowerment and shaping identity. We have new ways of making photographs and disseminating photographs. Not everyone had access to the equipment back then. But now everyone does. Ownership and authorship of imagery has shifted.”

Source

Plagiarism is the copying & pasting of others work without giving credit to the original author or artist. Plagiarized posts are considered spam.

Spam is discouraged by the community, and may result in action from the cheetah bot.

More information and tips on sharing content.

If you believe this comment is in error, please contact us in #disputes on Discord

Superb Article

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/14/lens/photography-african-women.html

Congratulations @dayrunner88! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click here to view your Board of Honor

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDo not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Congratulations @dayrunner88! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click here to view your Board of Honor

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDo not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Congratulations @dayrunner88! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!