I used to live in one of those stucco buildings in Los Angeles—the kind where the doors of all the apartments open to the same courtyard. Most of the tenants were recent immigrants. They came from Romania, Iran, Greece, Indonesia, India, Japan, Brazil, the Caribbean, England, and other places I’m no longer able to name. Thousands of sounds and echoes, understood by some, ignored by most, turned our cement patio into a modern Tower of Babel. All but two kindly grandmothers, widows who called to each other in Hebrew across the railings of the second-story walkway, spoke both English and their native language. The Iranians spoke Persian and Turkish, but not Spanish. So if the couple from Mexico City or the single mom from Nicaragua weren’t home, I was sometimes asked to help the Iranians communicate with a Salvadoran employee of their carpet cleaning business. The multi-lingual Persians assumed I could speak the language of Latin America, which, by coincidence, was true.

If it wasn’t an American pot where language and race all melted together, it was an eye-dropper sample of humanity under an urban microscope, something that might have silenced those who, claiming to yearn for a color-blind world, are endlessly asking people to separate their souls from their heritage in public tabulations that preserve our bad habit of perceiving differences between each other where there are none. There in that little cocoon of seeming diversity it was impossible to find much that was unique to any particular group of the earth’s people. They all stepped at pretty much the same pace through the universally familiar patterns of life—

—with one fiercely immortal exception.

Of all the possible compartments people imagine for cataloging each other, the two most enduring categories are the ones formed by the Great Divide between the species known as the human male and those of the separate and distinct species known as the human female.

The truth of this returned to me one day from the echoey courtyard of that social laboratory I lived in. I heard Manolo, an eight-year-old boy from Nicaragua, and the accompanying silence of our neighbor, a six-year-old girl from Jamaica. His voice pulled me out of the dreams of an afternoon nap like a lasso through my window: “Attack!” He’d make the command, pause ten or twenty seconds, and then repeat, “Attack! Attack!!” Failing in this general request, he tried a direct order, "Attack, Regina!"

It was the ancient Game of War. I remembered. One of my older brothers used to play it. His passion and enthusiasm would distract me from a fantasy game of my own and I’d pause to watch him, enthralled.

I couldn’t tell the bad guys from the good guys, couldn’t remember who was attacking whom, and more than once humiliated myself by referring to the “allies” as the “enemies.” So I worried, too. A constant observer of the ways of my big brother, I sensed that the difference between an enemy and an ally was an important thing to be able to keep track of, but it wasn't long before I gave up and just let the subject remain in the realm of Incomprehensible Stuff.

I could never see “The Russians,” but in the eyes of my brother and his friend, who at the age of eight could recite the entire history of the Second World War minute by minute, “The Russians” were, very clearly, right up there on the roof. Somehow, they knew, and I did not, that “The Japs” were on the verge of scaling the pink brick wall. And suddenly they’d know a whole bunch of “The Germans” were on the south side of the house, “infiltrating” the back yard in “preparation of an offensive.”

My brother and his freckled troops always, simultaneously, knew these things. They knew these things and, instantly, together, they all knew, as if by a force of telepathy, exactly how to respond. Without exception, they survived every single leap, tumble, fall, and dangerously unnecessary crash; every wound to the leg, back, head, and heart; every bomb, bullet, bayonet, and surprise attack.

I watched their acrobatics with unconcealed wonder. It was so entertaining that, quite naturally I thought, I wanted to play, too. It wasn't long before I committed the blasphemy of saying so.

They rejected me. It was as if they knew, once again, something I simply did not. Exasperated, disgusted, patiently, and in many other ways, they stated the rule, “Girls can’t play.”

This was one of many variations on an endless point of contention between my brother and me. It would begin with an argument over whether boys were better than girls and lead to my brother’s proof: “Name one thing you can do that I can’t.” I would stand there flummoxed, unable to name one thing, and very pissed off.

So telling me “Girls can't play” meant “War is declared.” It would be war, but a different sort of war. I, a girl, was going to play. If not that day, it would be the next, or the one after that, or somewhere in the eternity of a week or a month. But I would play.

I’d soon forget that firm decision, and not think of it again until the next time all the gun firing and grenade throwing and running for cover began. Engrossed in what then seemed like a detailed, complex dramatization of “Store,” my girl friend and I would hear the soldiers, kind of far away, shouting, squishing air and spit across their tongues at exactly the same moment kid-size bombs blew the oleander, garage door, or driveway into imaginary bits. We’d hear them, but not really notice them, until they’d invade us like a herd of hyenas perilously trapped by their invisible enemies with no way out except straight through our meticulously created “Store.” Just like that. One world destroying another, the boys would capture the girls’ full attention.

And my determination to have just as much rip-roaring fun as any boy would begin anew. Identifying my brother’s complete lack of interest in me as the cruelest sort of injustice, I became persistent. I followed him everywhere, repeating my plea day, after day, after long summer day: “Can I play?”

It was a dumb question. One that doesn't need to be asked if the answer is yes. But one afternoon, he answered it anyway. "You're The Nurse."

This came, not surprisingly, as a surprise. I wasn’t used to getting my way. But there it was. The impossible was suddenly possible. I’d have to live up to all my speeches. I’d have to pass the test.

Watching closely for clues, I got the impression an enemy was chasing us. In reality, I, trying desperately to keep up, was chasing my brother, well aware that his transparent pursuer was a lot more important to him than his visible nurse. It cornered us between the Clark’s and the Campbell’s tract houses, where my brother, hurled ten inches high and three feet across from the force of a resounding silent explosion, came rolling with arms and feet flapping like the blades of a roto-tiller across the dichondra that was our fox hole.

It was time to prove my worth and thereby stake a precious claim on a perpetual invitation to the Game of War. My brother’s buddy kept lookout. My wounded patient squirmed. He moaned. He got bored as he waited for the sister to start being The Nurse. But while he and his friend carried on like the virtuosos they were, I was paralyzed by blank confusion. I had not even a faint image of what I was supposed to do.

I groped for an idea. Nothing came to me. Stalling for time, I tapped the soldier in high-top sneakers with my open hands. Not good enough, I knew. The act would have to be developed. So I tapped him again, this time on the crown of his Giants baseball hat, and twice on the word “Celtics” that shielded his chest. And then, caving to a sense of pressure to perform, I announced: “Okay, you’re all better.”

As invincible as John Wayne, as sanguine as Bella Lugosi, and as disappointed as Thomas E. Dewey, my brother sprang back to life. I remember his exact word: “NOOOooooo!!!”

There. I’d proved it. Girls, in fact, could not play. This time it really wasn’t irrational loyalty to a mere habit that generations of both men and women keep passing off as truth. It was scientific observation. Even my brother, my one-hundred percent male brother, could have handled The Nurse job better than I could. And there would be no second takes, no gradual induction, no patient instruction. I’d had my chance, and I failed.

“You’re The Nurse.” I don’t remember any pleasure in the triumph. If there was any, and there surely must have been, it was obliterated by what was to follow. I wish I could say it had been obliterated because I was quick enough to see that his letting me be The Nurse was nothing less than a brilliant strategy. It shut me up, and then got me finally, even willingly, to leave him alone.

Quick enough I was not. It took me about 20 years to figure it out. Now I can see how, in some subtle way, my brother had flattered me. I’m pretty sure it had occurred to him what vicious pleasure could have been his if he’d signed me up to be The Enemy, and how logically he could have excused himself from causing my death with the truthful defense, “She asked for it.” I was just a girl, but at least I got to be on his side. And I learned when opportunity came steamrolling through my door that day that, like the Mudpie Game and the Game of House, the War Game is sheer improvisation--no rules, really, just something you feel, one of those knacks you either have or don't. I didn’t.

I remembered the Game of War until the voice that had floated me to the past snapped me back to the present--the present where, as for eternity, the rhythm of life of the children of Nicaragua, Jamaica, the United States, and the rest of the world is so much the same.

And where Manolo, who didn’t have a single boy to play with that day, was still calling, "Attack! Attack!! Attack, Regina! ReGINa!! ATTACK!!!"

I loved this one, 100% humor. Thanks for sharing :)

Thank you! Hugs...

Thank you so much Annie. Will look forward for more content from you.

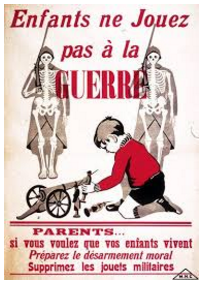

Super your article. You are totally right. I liked the small image at the top (because I am French) I will follow your blog because I like your ideas you are awsome

Merci beaucoup! Et... um... pareilment. I will follow you as well! Looking forward to reading what you have to say.

Don't the French say, "Vive la différence!" ?

What do you want to say for "Vive la différence!"?

I mentioned it because it's a fit for the story you liked, and you're French. :o)

Oh! We say, "Vive la différence!"

Congratulations @andrea-annie! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your own Board of Honnor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about this award, click here