In 1998, when Arunachalam Muruganantham saw his wife using old rags for sanitary pads, he made a prototype that failed terribly. Thereafter, he used different materials and came up with new models for sanitary pads every month. Since there was a month gap between each prototype tested by his wife, he had no other choice except to ask for a few volunteers from a nearby medical college. Though a few female students agreed to try them, they were shy to give him the right feedback. So Muruganantham decided to test them himself.

It took him two years to find the right material and another four years to come up with a way to process it. The result was an easy-to-use machine for producing low-cost sanitary pads. With the imported machines costing more than $5,00,000, Muruganantham's prototype came at just $950. As a result, women’s groups or schools can buy his machine, produce their own sanitary pads, and sell the surplus. In this way, Muruganantham's machine has created jobs for women in rural India. He has started a revolution in his own country, selling 1,300 machines to 27 states, and has recently begun exporting them to developing countries all over the world.

In 1998, when Arunachalam Muruganantham saw his wife using old rags for sanitary pads, he made a prototype that failed terribly. Thereafter, he used different materials and came up with new models for sanitary pads every month. Since there was a month gap between each prototype tested by his wife, he had no other choice except to ask for a few volunteers from a nearby medical college. Though a few female students agreed to try them, they were shy to give him the right feedback. So Muruganantham decided to test them himself.

It took him two years to find the right material and another four years to come up with a way to process it. The result was an easy-to-use machine for producing low-cost sanitary pads. With the imported machines costing more than $5,00,000, Muruganantham's prototype came at just $950. As a result, women’s groups or schools can buy his machine, produce their own sanitary pads, and sell the surplus. In this way, Muruganantham's machine has created jobs for women in rural India. He has started a revolution in his own country, selling 1,300 machines to 27 states, and has recently begun exporting them to developing countries all over the world.

Today, Muruganantham is one of India’s most well-known social entrepreneurs and TIME magazine named him as one of the 100 most influential people in the world in 2014.

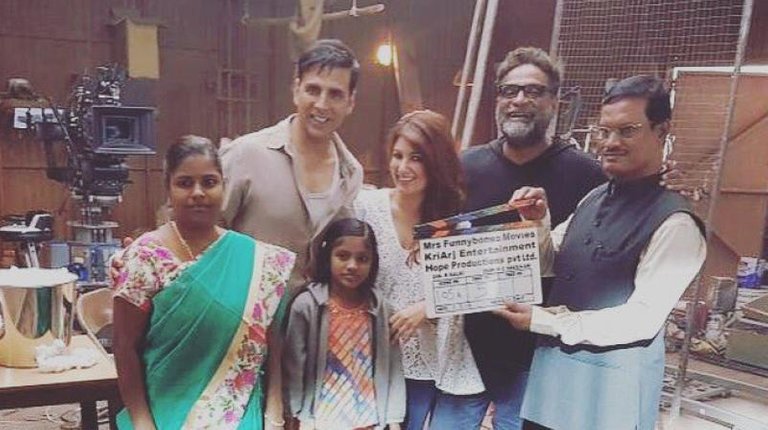

A Bollywood movie named PadMan has been made out of Muruganantham's story, starring Akshay Kumar, Radhika Apte, and Sonam Kapoor. The trailer which was released recently gathered more than 20 million views on YouTube. It was Twinkle Khanna, the lead actor's wife, who came up with the idea for this movie.

According to a report by The Quint, Muruganantham, also known as ‘India’s Menstrual Man’, has already been widely documented and reported about by both the Indian and international media. Twinkle herself has based the story ‘The Sanitary Man from a Sacred Land’ in her new book The Legend of Lakshmi Prasad on this Padma Shri winner.

Editor's note: The trailer for Akshay Kumar's Padman — released on 15 December 2017 — has brought the focus back on Arunachalam Muruganantham, the innovator/social entrepreneur on whom the film is based. Muruganantham is hailed for pioneering the manufacturing of low-cost sanitary napkins in India, and also kickstarting a menstrual hygiene movement in the rural areas where it was the need of the hour. This piece, which previously appeared in Governance Now, profiles Muruganantham's incredible story.

Operating on a single machine at a time, Arunachalam Muruganantham explains his every move in broken English to four village women who watch carefully as he delicately handles lumps of cotton-like substance and rolls them to make sanitary napkins.

A young management student translates the instructions into Hindi and the women nod, following the method that they will soon adopt. The final product, after the raw material passes through four other machines, is a thick, rectangular sanitary napkin costing just Re 1. That’s about one-fifth the cost of an average branded sanitary napkin.

The women in the small, carpeted room, where the machines are installed, take turns to examine the outcome of the two-minute labour. The youngest among them, Kumari Sharda Rana, 18, is too shy to even touch it.

Eight women from Sara Saria village near Khatima town of Udham Singh Nagar district, Uttarakhand, will soon manufacture and package these napkins under the brand name of ‘Sahyogpath’ and each will get Rs 1,500 as monthly salary. It will be marketed and supplied door-to-door by many others like them.

This small business, set up at farmer-innovator Ashok Kumar Singh’s home, employs eight women in two groups of four each, who have been working in shifts of four hours a day since 1 April. Muruganantham taught the women how to operate the machines and when he returns to his home in Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu, he will have given Sara Saria not just hygienic sanitary napkins, but also sustainable employment to these women.

Once the project starts running smoothly, these eight women will join hundreds of others who have benefited from 47-year-old Muruganantham’s innovative device.

Most of these women have no clue about how this genial, soft-spoken man hit upon this idea — the saga of a common man, a chance incident and a bright idea backed up by a lot of hard work, the trial and error way.

The idea of making sanitary napkins first struck him a decade ago when he once saw his wife trying to steal a piece of dirty cloth into the bathroom. He later found out that she used it during menstruation.

“The cloth my wife was using was so dirty, I would not even use it to wipe my scooter,” Muruganantham told a gathering of more than 60 village women at the inaugural function of the venture in Uttarakhand.

“I realised that so many women like her must be using such unhygienic means during their periods,” he added as many women covered their mouths with their dupatta, turned to their neighbours and giggled.

Coming from a below poverty line family, the task was indeed tough for Muruganantham. It was his curiosity and determination, he says, that kept him going.

He was in Class Four, studying in a convent school in 1979, when his father died in a road accident. Within three months, his family was left with no money and he moved to a municipal school. His mother started working on a farm for seven rupees a day. He dropped out of school after Class 10 and joined a workshop where he made metal doors, grills and staircases. He worked there for seven years to help his mother and to support two younger sisters.

In 2000, Muruganantham researched extensively on sanitary napkin-making companies in the US and started experimenting.

“Looking at a sanitary pad one would feel it is cotton that these multinational companies use. So my first experiment was with cotton, but it did not work as cotton cannot hold liquid,” he says.

The first sanitary napkin he made was cotton wrapped in a medical cloth which he gave to his wife and asked for her feedback. He was disappointed when she said that it was useless and that she was going back to using that piece of dirty cloth.

For more useful feedback, he went to a medical college and gave the napkins to girls there, thinking they were future doctors and would not be shy of giving their opinion. When he did not get frank responses from them, he prepared feedback forms which he asked them to fill.

“One day, when I went to collect the forms, I saw that two girls were filling out forms for the rest. This was not the kind of feedback I wanted; so I stopped the research,” he says.

Strange though it may sound, he started using the napkin himself. “I wore a napkin, tied a football bladder full of goat’s blood to my waist and attached a pipe to it. But this technique did not work either.”

In what he calls his last resort, he asked the medical college girls to collect their used sanitary napkins and keep them in a corner in one packet. He collected these napkins and opened them in his backyard.

“When my mother saw me doing this, she made a hue and cry and thought I had gone mad. She left me and went to stay with my sisters,” he says, smiling as he recalls the scene.

Upon analysing the used napkins, Muruganantham realised that the multinationals used cellulose, not cotton. So he imported a cellulose sample from the US, anticipating a substance as fluffy as cotton.

“They sent me a thick sheet. I would just hold the sheet in my hand and wonder how they made sanitary napkins with this. Then one day I tore the sheet and saw that it was made of fibres. The sheet was to be torn and made into fibres. I now needed a machine to make the pads,” he said.

“The plant set up in the US cost not less than Rs 4 crore, which, of course, I could not afford. I understood the technique and designed simple machines that performed the same task but took up only a room’s space.”

Today, his workshop — under the name of Jayaashree Industries — produces sanitary napkin-making machines in bulk. He has supplied the units to over 200 districts in India.

Though the scope of making profits from this venture is huge, he follows one golden rule: he promotes his machines only through women’s cooperatives.

“The idea is not only to make money but to bring about an attitudinal change,” he says.

Muruganantham believes only a woman can reach out to other women when it comes to discussing issues like menstruation. Of course, he considers himself an exception to the rule (and indeed he is).

A room’s space is exactly what he needs to bring about a habit change, generate employment at the grassroots level and make these women financially independent — and address a huge issue of the governance of women’s hygiene in the country.

Back at the Sara Saria workshop, the red ribbon tied outside the old wooden door of the room — now the working space of eight young volunteers from the village — is cut by the eldest woman of the house, Ashok Kumar’s mother, Atrwas Devi, 75.

Attending to the guests on the occasion was Sonia Suryavanshi, Ashok Kumar’s 26-year-old daughter who spearheaded this concept in the village, going house-to-house to spread awareness about menstrual hygiene.

“The reason why women here still use cloth during menstruation is due to their habits and not because of lack of money,” says Suryavanshi. “This is a fairly prosperous village and they all know about the problems they may face using cloth, but they do not want to switch to a sanitary napkin.”

Apart from educating these women and telling them about locally produced napkins, Suryavanshi, with a team of seven students, provided them an opportunity for part-time work. Their weeks of efforts finally showed on the big day when women came in groups to attend the inauguration.

“You may suffer from backaches, white discharge from the vagina and ulcers if you do not maintain hygiene during your menstruation. Also, most families in villages isolate women during this time. Most of them stay in one room for over five days and do not clean or wash. This can have serious impact on their health,” says Dr Sunita Chuphal Raturi, the gynecologist who works in Khatima, as the women listen attentively.

Holding a sample in her hand, Anti Devi, one of the women who was trained to make the napkins, says, “This is better than the ones available in the market. It is thick and we can see how it is made. We will work with dedication and sell it to all the women in the village.”

The women throng the table where sample packets of the napkins are lined. Within minutes, all packets, each costing Rs 6 for three pieces, are sold.

A week after the inauguration, Suryavanshi was overjoyed. “We have received orders for 12,000 packets from the women volunteers, under the central government’s National Rural Health Mission, from the nearby villages. They are very impressed with this project and have taken up the responsibility to market it. We are thrilled. The work will begin in full swing now,” she says.

Most of the women who have volunteered for the project and those who bought the packets at the inauguration are illiterate; some have not studied beyond Class Five. Though money is not a problem at their homes, they still labour as daily wage worjers in fields.

The project, a collaborative effort of students from the Indus World School of Business (IWSB) college in Noida, Uttar Pradesh, and a Students in Free Enterprise (SIFE) team from Britain’s Sheffield University, has given Uttarakhand its first indigenously developed sanitary napkin-making machine. Each contributed Rs 1,00,000 and bought a unit of the machine from Muruganantham, who sold it at cost price of Rs 1,40,000. The remaining Rs 60,000 will be used for paying salaries to the eight volunteers until the venture turns profitable.

“The idea is not to give money to people but to give them projects which can be sustained and generate revenues. We give them a set-up. We want them to run it and to earn money from it,” says 21-year-old Sagnik Mukherjee, a member of SIFE, a non-profit organisation run by students of various universities in several countries.

“After setting up projects we teach them market economics, business ethics and knowledge transfer as well. We teach them how to price the pad, market it and sell it,” says Mukherjee.

Once the venture picks up, the profit will be shared by the women volunteers (50 percent), the IWSB team (30 percent) and the SIFE team from Sheffield (20 percent).

“A lot of women across the country are employed in hazardous and high drudgery jobs like beedi making, match-stick making and in various chemicals industries,” says Muruganantham, “If we give them sustainable non-hazardous work like sanitary napkin-making, it will be far more beneficial for them.”

His machines are now in Massachusetts, California

Muruganantham set up the first unit to make sanitary napkins at his home in Coimbatore in 2005; the unit in Uttarakhand's Sara Saria village is his 212th. Since 2006, when he gave his first unit to the All India Women‘s Organisation in Dehradun, his expertise has spread across India and abroad mainly through word of mouth. He has never advertised his product. “Instead of giving 50 units to one organisation, I give them one, train four women and give the unit to them," he says.

Muruganantham has no share in either the profit or the loss they make, though he still takes care of the requirement of raw material at any unit installed. He imports cellulose from the US and the medical cloth from Germany. The UV tube used in the sterilising machine, in which the pads are put for a minute once ready, is ordered from the Netherlands. “The raw material available abroad is cheaper and to import and export, an IEC (import export code) licence is required, which I have," he says. Travelling for 22 out of 30 days and installing around five units a month, he earns around Rs 60,000 to Rs 70,000, which covers just the rental for storing raw material and cost of transportation. One unit can be operated by four women at a time and in a day, 800 to 1,000 sanitary napkins can be produced. “One lakh units installed means 10 lakh jobs generated,” he says.

In 2006, the Indian Institute of Technology-Madras honoured Muruganantham for his innovation and in 2009 he won an award at the National Innovation Foundation’s (NIF) fifth National Biennial Competition for unaided grassroots innovations. His technology, which he sells for Rs 1.4 lakh (inclusive of the raw material), has been patented by the NIF. NIF gave him Rs 8 lakh under the Micro venture Infrastructure Finance Scheme, which he has to repay at an interest rate of 12 percent.

All 21 districts of Haryana have at least one such unit. However, Orissa and the North East are still untouched, Muruganantham says.

“Last month, an individual from California bought the machinery and one unit was set up at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,” Muruganantham says proudly. “These machines will soon be seen in Kenya, Nigeria, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh as well.”

Instead of exporting the bulky machines to far-off places in Africa, Muruganantham will first teach them how to manufacture the machines. Once the unit is ready, he will teach the technique of making sanitary napkins. “This will cut down the cost of exporting the machines from India and will be much cheaper for those poor countries,” says the innovator.