Note: What I am sharing with you right now is the Term Paper I turned in at my school for a class called "Introduction to the Allied Fields of Physical Education, Fitness, and Sport." It's nothing grand, ground-breaking, or extraordinary, but simply the first in a long list of essays that I plan on writing both inside and outside of the classroom. Please ask for the PDF or a Google Document if that suits you better, but this is just a straight-up copy-and-paste job. Multiple links have been added for further research outside of my citations. This post another lengthy, drawn-out intro to myself and how my mind works.

Any feedback would be greatly appreciated--criticism of my writing, the essay's content, the argumentation, the fact that only five pages was required to complete this assignment (I am returning as an undergrad, for those of you who don't know). Also, the citation method is APA (6th Edition). Well, here goes nothing.

Black male athletes—and the utility of the black male body—have been the subject of much debate in America for at least the past three centuries because, other than Native Americans, no other group can convey the pervasive nature of inherent, structural inequalities within this nation. America’s emergence as an imperial force requires its citizens to behave in an imperialistic manner; people must use every avenue and advancement available to confirm the motif of dominance. Sports and games, and the organization and commercialization thereof, provide perhaps the quintessential avenues by which one group of people can achieve this goal—demonstrating superiority by exploiting the brute force and sheer will of “lower-rung” participants to develop some semblance of a self-identity and self-efficacy without any genuine concern for their mental well-being, which one can conclude is the exact opposite of the goals set forth by Clark Hetherington (Siedentop, van der Mars, 2012, pp. 49-51), the “father of modern physical education,” and Donald Hellison, progenitor of the landmark 1973 book Humanistic Physical Education (pp. 53, 62-64) and the consequent Personal and Social Responsibility Model.

Hetherington’s four pillars of a new physical education protocol—organic, psychomotor, character, and intellectual education—are collectively still considered by many to be the gold standard by which every approach to health and fitness is measured because they indicate the need for a complete, sufficiently competent human being to fully participate in our constitutional republic. One could argue, however, that Hetherington was ill-prepared to consider how or this ideal would translate to the development of non-white children at the apex of the Jim Crow era. Additionally, it was impossible for him to anticipate a growing body of evidence showing how chronic racism-induced stress affects the development of black boys even before they are born (Kramer and Hogue, 2009), how discrimination increase mortality rates (Barnes et al., 2008), and how black college athletes are subjected to an educational system that reinforces racist perspectives so much that even black non-athletes suffer (Hawkins, pp. 114-115). Hellison’s Personal and Social Responsibility model is a more modern approach that, according to Siedentop and van der Mars, is still used to guide at-risk urban youth (53), but it still does not directly combat utilization of the black male body for maintenance of White Supremacy.

Inherent in these concepts, among many other physical education models and social movements that have spurned from innovative technological, economic, and intellectual advancements, is the notion that any human being has the right to view the physical/muscular realm and the emotional/psychological realm not as existing in separate vacuums but instead symbiotic whole that can determine future ideals. The enforcement and impact of slavery, Jim Crow laws, White Supremacy, along with the ubiquity of unprecedented media coverage and sponsorships, lessens the possibility of this threshold by overemphasizing the notion of “spectacle” at the expense of “revolution” and “justice” as reported by Mark Naison:

Through television coverage and heavy journalistic promotion, mass spectator sports have been made one of the major psychological reference points for American men,…The corporations that finance this activity are capitalized at billions of dollars and are granted political privileges…that are normally extended only to “public utilities.” This special status is reinforced by the American educational system, which sponsors an intensive program of spectator sports from grade school up and explicitly seeks to “train” athletes for professional ranks in its higher levels. (95)

Naison proceeds to use international examples—cricket in India, baseball in Japan and the Spain-influenced Caribbean nations, soccer/futbol in South America, the potential for Anti-American revolutionaries to use sports to show America as hypocrites—along with Jackie Robinson’s being the “magical or acceptable negro” (in contrast to multi-talented yet outspoken athlete Paul Robeson) to underscore the lengths that the White Anglo-Saxon Protestant elite would go to maintain a façade of racial harmony via sports and sports journalism. Naison is essentially saying that sports as practiced through the exclusionary varsity model are subject to the same financial, technological, environmental, legal, and socioeconomic influences as all other social institutions. Failing to understand that a game or sport does not exist in a vacuum, independent of concepts derived from humanity’s beliefs, attitudes, and ideologies, means that one fails in understanding humanity itself. Avoiding this failure means developing an understanding of how racism, imperialism, and the struggle for obtaining self-efficacy operates in different stages of America’s historical eras: the slavery and Antebellum period, the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras, the Civil Rights Movement, and contemporary society (after the 1984 U. S. Supreme Court ruling NCAA v. Board of Regents).

Note/Break: You can read the official document and ruling HERE.

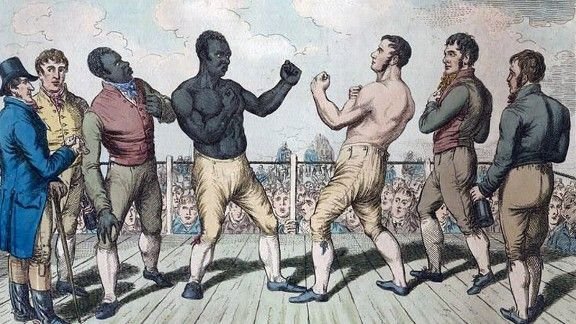

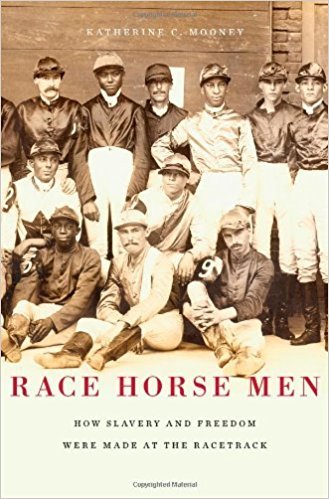

Perceptions of American race- or skin color-based slavery are usually one-dimensional and do not take the slaves’ propensity to seek recreational activities into consideration. Sports history scholar David K. Wiggins (1980) makes this observation on the portrayal of slaves in the Old South: “Most of the earliest studies done on Southern plantation life portrayed slaves as people without a culture, without philosophical beliefs, and without educational instruments on their own…As such it was assumed that slaves held no strong values or convictions and that they were without a coherent culture or social organization of their own” (p. 21). Current evidence says otherwise: sports and competition were vital parts of many African tribes because they were symbolic of the transitional phase into adulthood and displayed masculine prowess of individual tribe members, The transitional phase is best shown through the ingenuity and self-expression that our predecessors needed to develop what we consider sport- and performance-related skills (Rhoden, 2006, pp. 50-59), which was achieved by the variety of activities—wrestling, jumping/high-jumping, running, hunting and stick games, marbles, horse racing, and ball sports with make-shift bats (Griffith, 2010, pp.64-72). Further, while black and white children definitely played together and even formed rare life-long friendships, the young black kids were always in subordinate roles and did not get to experience any semblance of a dominant position until they could wander around the borders of the masters’ plantations, the boys and their fathers could go fishing, and/or beat their fellow slave and Caucasian peers in some athletic competition (Wiggins, 1980, pp. 33-36). As the sports culture grew in the 18th and early 19th Centuries, new sports like quarter-mile racing, “Town Ball” (the pre-cursor to baseball), American-style wrestling, and boxing would rise. According to Rhoden, boxing and African-Americans’ roles in sports culture entered a new stratosphere in parts of Western Europe because former slave Tom Molineaux participated in the first “Fight of the Century” against English boxing champion Tom Cribb and “show[ed] how the tools of enslavement could become the tools of liberation” (p. 47). Meanwhile, horse racing exploded and famous races took place throughout the East Coast because wealthy slaveowners owned enough property to breed horses and use slaves as jockeys (e.g. Austin Carter, Abe Hawkins) since they did not threaten White Supremacy despite their levels of success.

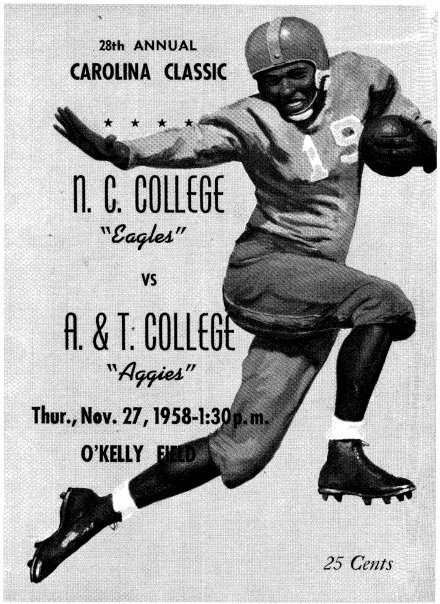

The Civil War, Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras brought about vast changes in nearly every aspect of American society as the popularity of baseball, boxing, and cycling exploded with football and basketball not far behind. The Dred Scott v. Sandford Supreme Court decision were among the first laws in a very long list of judicial decisions that excluded many African Americans from almost every aspect of society including sports. This landmark decision was followed by the “separate but equal” doctrine established in Plessy v. Ferguson, “Social Darwinism,” “100% Americanism,” and the Black Codes, the state statutes used to undermine the 13th Amendment. Not only were rules made to exclude as many blacks as possible, but there were also regulations in place to ensure that white athletes would win over blacks as often as possible. Football, along with baseball, was especially regulated with a racial tinge because “Cultural conservatives disliked the sport’s Yankee roots, while southern evangelicals condemned most ‘worldly amusements’ including sports” (Martin 2010, p. 4). Despite these concerns, football’s violent nature, and the engenderment of black college football teams, the “gentleman’s agreement,” an informal non-verbal express contract barring black players from playing at white and/or Northern schools, reinforced Southern slavery-based ideologies and capitulation to Social Darwinism and White Supremacy. Baseball underwent the same phase as this agreement prevented black baseball players from entering the International Association by 1890 and would eventually be carried over by Judge Kennesaw Landis, modern baseball’s first commissioner. Quality black football players were not even allowed to be seen with their respective Northern teams unless some of them were permitted to include one or two black players. These “token blacks” were invited to fill quotas and play the “magical negro-who-also-saves-the-day” role because white people thought they were so superior athletically that they could single-handedly win games. When a black athlete is only there to give mesmerizing or otherworldly performances when the game is on the line or else take the fall for losses without complaint (or else he will be considered too “uppity” and cannot “stay in his place”), then he burdened with the “superspade” label (Davis, 1994). Many pre-Civil Rights black athletes like boxing champion Joe Louis were employed as disconnected manifestations of a white-washed American ethos absent of political stances (Sklaroff, 2002, 970-973).

Numerous attempts by black athletes to integrate and directly dispel stereotypes about black people—including but not limited to Jesse Owens’ Berlin Olympics performance, Paul Robeson’s stance against McCarthyism, the aforementioned Louis, Wilma Rudolph and the Tennessee State Tiger Belles women’s track team, Texas Western’s victory over Kentucky in the 1966 NCAA Men’s Basketball Championship, the inaugural HBCU football Classic Grambling State-Morgan State football game in September 1968 (months after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and John Carlos and Tommie Smith’s Black Power demonstrations), the integrated USC Trojans’ football team beating Bear Bryant’s all-white Alabama squad 42-21 in September 1970, Curt Flood’s battle against Major League Baseball’s antitrust exemption in Flood v. Kuhn, Arthur Ashe, and the exploits of football great Jim Brown and basketball legends Bill Russell and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar—have created new problems because of continued racist attitudes, exponentially more media coverage and increased salaries. Television revenue for college athletics exploded after the 1984 NCAA v. Board of Regents Supreme Court ruling while more college and professional teams built new stadiums and revamped their recruiting and marketing techniques, setting the table for both areas acting as industries in and of themselves and introducing “racial stacking,” or the employment of preconceived notions to place certain players of certain races in predetermined positions (Woodward 2004, pp. 357-61, 371-73). Much debate has arose about the disparities in profit margins between schools based on the aforementioned television revenue, contracts for media rights, licensed apparel (e. g. jerseys, hats, championship T-shirts), stadium naming rights, usage of athletes’ images in video games, and reinforcement of Title IX. According to Billy Hawkins (2010, p. 102), “Black male athletes are invisible as men but strategic in bearing the burden of generating revenue for athletic departments…” and “Black males find themselves locked in this perpetual relationship of servicing the needs of the White establishment.”

Works Cited

Barnes, Lisa L., Mendes de Leon, C. F., Lewis, T. T., Bienias, J. L., Wilson, R. S., & Evans, D. A. (2008, July). Perceived Discrimination and Mortality in a Population-Based Study of Older Adults. (B. Selzer, Ed.) American Journal of Public Health, 98(7), 1241-47. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114397

Davis, T. (1994). The Myth of the Superspade: The Persistence of Racism in College Athletics. The Fordham Urban Law Journal, 22(3), 616-97.

Griffith, Jon (2010, June). Sports in Shackles: The Athletic and Recreational Habits of Slaves on Southern Plantations. (E. Neis, Ed.) Voces Novae: Chapman University Historical Review, 2(1), 59-79.

Hawkins, Billy (2010). The Black Athlete's Racialized Exeriences and the Predominantly White Intercollegiate Institution. In B. Hawkins, The New Plantation: Black Athletes, College Sports, and Predominantly White NCAA Institutions (pp. 102, 108-120). New York, NY, USA: Palgrave MacMillan.

Hogue, M. R. (2009, May 28). What Causes Racial Disparities in Very Preterm Birth? A Biosocial Perspective. (M. A. Ibrahim, Ed.) Epidemiologic Reviews, 33(1), 84-98.

Martin, Charles H. (2010). White Supremacy and American College Sports: The Rise of the Gentleman's Agreement, 1890-1929. In C. H. Martin, Benching Jim Crow: The Rise and Fall of The Color Line in Southern College Sports, 1890-1980 (pp. 1-4, 6, 9-22, 24-26). Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Naison, Mark (1972). Sports and the American Empire. Cambridge, MA: New England Free Press.

Rhoden, William C. (2006). Forty Million Dollar Slaves: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Black Athlete (1 ed.). (A. Pande, Ed.) New York, NY: Crown Publishers.

Siedentop, Daryl & van der Mars, H. (2012). A Primer on the Twentieth Century Philosophical Influences in Physical Education. In D. S. Mars, Introduction to Physical Education, Fitness & Sport (8th Ed.) (pp. 49-50, 52-3). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Sklaroff, Laura R. (2002, December). Constructing G. I. Joe Louis: Cultural Solutions to the "Negro Problem" during World War II. (S. Andrews, Ed.) The Journal of American History, 89(3), 958-983.

Wiggins, D. K. (1980, Summer). The Play of Slave Children in the Plantation Communities of the Old South, 1820-1860. (W. a. Vamplew, Ed.) Journal of Sport History, 7(2), 21-39.

Woodward, J. R. (2004, December). Professional Football Scouts: An Investigation of Racial Stacking. (P. D. Michael Atkinson, Ed.) Sociology of Sport Journal, 21(4), 356-75.

© copyright - all rights reserved by @tinashe

👉 CLICK HERE

Congratulations! Keep it up!

Wellcome, It is great to have you here!. If your here to make money then its hard work....but don´t give up!

Hi, as a sign of my support for the tag #sports and #football, I vote for you and begin to follow you.

Welcome to Steemit @snottistcyr, I have upvoted and sent you a tip. Check my blogs if you are looking for tips on how to earn more Steem and SBD.

Congratulations @snottistcyr! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

SteemitBoard World Cup Contest - The results, the winners and the prizes

Congratulations @snottistcyr! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!