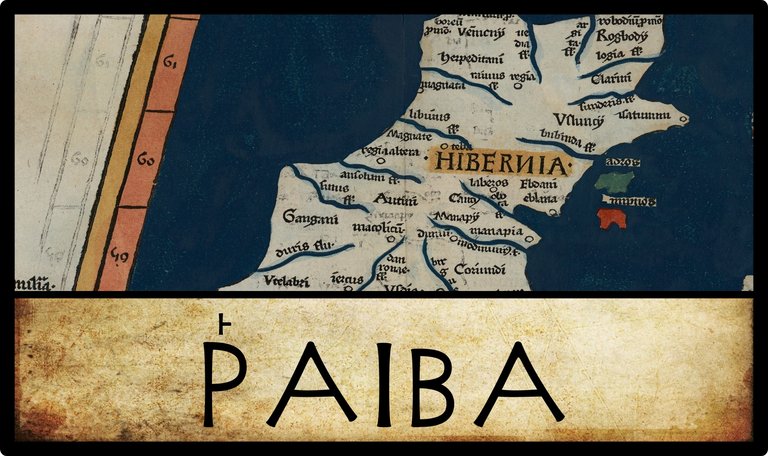

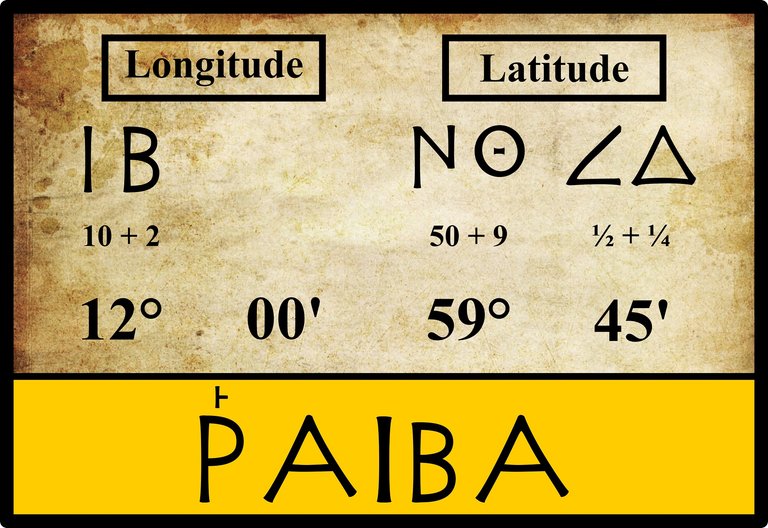

In his Geography, Claudius Ptolemy records seven inland “cities” in Ireland. Ῥαιβα [Rhaiba] is the second of these:

| Greek | Latin | English | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ῥαιβα | Rhæba | Rhaiba | 12° 00' | 59° 45' |

Source: Nobbe 66, Wilberg 103

As I mentioned in the previous two articles in this series, in ancient Greek an initial rho, Ρ, always takes a rough breathing:

13. Every initial ρ has the rough breathing:_ ῥήτωρ orator_ (Lat. rhetor). Medial ρρ is written ῤῥ in some texts: Πυῤῥος Pyrrhus. (Smyth 10)

Consequently, Ptolemy’s Ῥαιβα is sometimes transcribed into Latin script as Rhaiba or Rheba (Müller, Wilberg) and sometimes as Raiba or Reba (O’Rahilly, Heiermeier), depending on whether the transcriber believes that the original Celtic toponym had initial Rh- or R-.

Variant Names

Ignoring variations in accents, which date from Byzantine times, only one variant reading of the name of this settlement has been recorded by Ptolemy’s modern editor Karl Müller (1883):

| Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| Müller, Wilberg, Nobbe | Ῥαιβα | Rhaiba |

| X, Σ, Φ, Ψ, Arg | Ῥεβα | Rheba |

X is Vaticanus Graecus 191, which dates from about 1296. It is believed that this manuscript preserves a very ancient tradition. Ptolemy’s description of Ireland is on folia 138v–139r.

Σ, Φ and Ψ are three manuscripts from the Laurentian Library in Florence: Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 9 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 38 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 42.

Arg is the Editio Argentinensis, which we have met several times before. It was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513. Argentinensis refers to Straßburg’s ancient Celtic name of Argentorate.

Variant Coordinates

All manuscript sources agree on the coordinates of Rhaiba given in the main body of the Geography. Curiously, the only variant coordinates are provided by Ptolemy himself:

Ptolemy’s Geographike Hyphegesis (GH/Geography) compiled in about 150 AD contains a location catalogue in Books 2–7 with about 6,300 ancient localities and their positions expressed by geographical longitude Λ and latitude Φ. 360 of these localities are additionally listed with coordinates in Book 8 of the Geography. In contrast to the location catalogue, the positions in Book 8 are expressed by means of:

– the time difference A (in hours) from the location to Alexandria,

– the length of the longest day M (in hours) at the location,

– the ecliptic distance S (in arc degree) of the sun from the summer solstice at the time when the sun reaches the zenith (for locations between the tropics).The localities in Book 8 are selected cities, the so-called poleis episemoi (“noteworthy cities”). They are arranged in 26 chapters; each chapter is related to one of the maps Ptolemy divided the Oikoumene into (the inhabited world known to the Greeks and Romans) ...

A conversion of the A- and M-data in Book 8 into geographical coordinates can be found in Cuntz (1923) and in Stückelberger and Mittenhuber (2009). (Marx PDF 1-2)

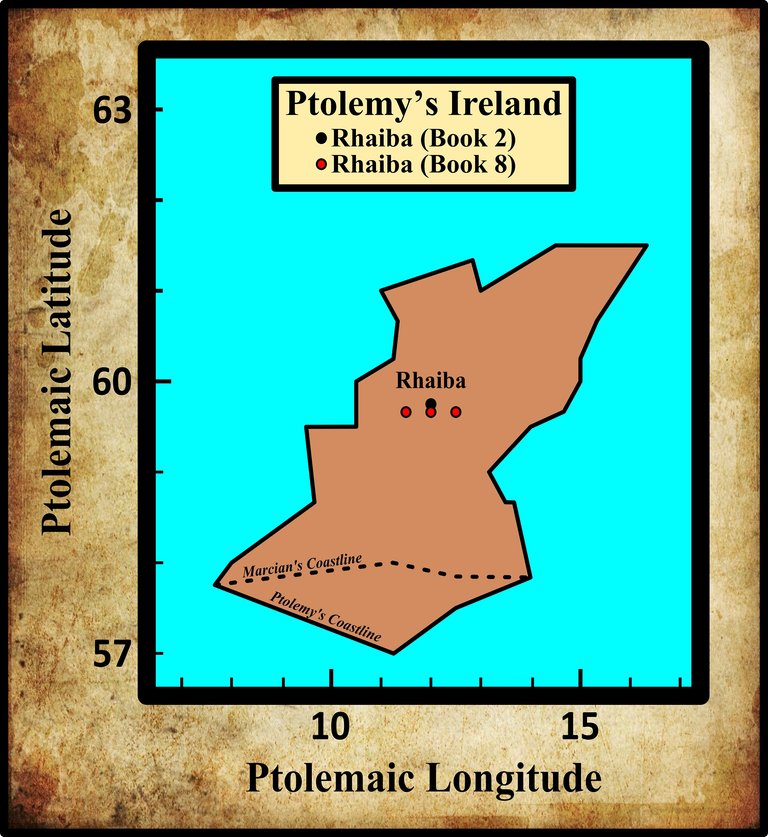

For Ireland, Ptolemy chose two noteworthy cities, Ivernis and Rhaiba. The relevant passage from Book 8 reads:

§4 The noteworthy cities of the island of Ireland ...

§5 Rhaiba’s longest day is 18 hours and 35 minutes long, and this city is separated westwards from Alexandria by three and one fifth hours.

(Nobbe 2:197, Ptolemy 8:3:4-5)

The time difference between Alexandria and one of Ptolemy’s noteworthy cities is relatively easy to convert into degrees of longitude: 24 hours corresponds to 360°, or 1 hour to 15°. Therefore, his estimate of Rhaiba’s temporal distance from Alexandria—three and one fifth hours, or 03:12—corresponds to precisely 48° degrees. But to convert this into a longitude, we need to know the longitude of Alexandria—and this is where things become messy:

Ptolemy gives two different values for [the longitude of Alexandria] in the Geography, in the location catalogue [4:5:9] 60° 30' ... and in Book 8 [8:15:10] 4 h[ours] (8.15.10; the distance between Alexandria and the zero meridian); in GH 7.5.14, he gives both values. The difference between both parameters is ... 30' = 2 min[utes of time].

Therefore, Ptolemy’s three and one fifth hours corresponds to a longitude of either 12° 30', which is 30' further east than he gives in Book 2 (about 23 km), or 12° 00', which is the longitude quoted in Book 2.

Karl Müller calculates 11° 30' for the first of these. He believes that the time given in Book 8, 3+1/5 hours, is a rounding for 3+1/5+1/30 hours, where the addition of 1/30th of an hour, or 2 minutes, pushes Rhaiba a further half-degree to the west of Alexandria. But 48° 30' west of 60° 30' is 12° 00', which would make Books 2 and 8 agree. To get 11° 30', we must use 60° 00' for Alexandria’s longitude, whereas Müller specifies 60° 30' (Müller 80). Nevertheless, if we accept Müller’s emendation of Book 8’s time, this gives 11° 30' and 12° 00' as the two possible longitudes of Rhaiba. In defence of Müller, Ptolemy does state categorically (Geography 8:2:1) that the time differences in Book 8 are approximations only (Mark PDF 3). Therefore, it is always possible to choose an appropriate emendation to ensure that the longitudes in Books 2 and 8 agree with each other.

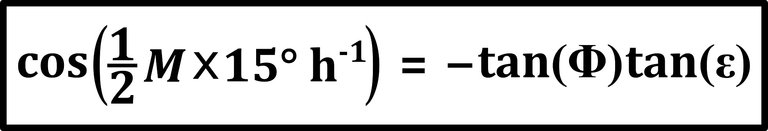

Turning to the latitude, Ptolemy believed that the length of the longest day varied from 12 hours at the equator to 24 hours at the arctic circle. But the relation between the maximum length of day (M) and the latitude (Φ) is not a simple linear one, and it also involves an estimate of the latitude of the arctic circle (Φ = ε):

The length of the longest day M increases from 12 h at the equator (Φ = 0) to 24 h for Φ = 90° – ε. Ptolemy derives the computation of Φ from M and vice versa in his Mathematike Syntaxis (MS) 2.3. The modern formulation of that relation between M and Φ is:

... Ptolemy does not explicitly mention the ε underlying the conversion between Φ and M in the Geography. In GH 7.6.7 he gives the ratio ε : π/2 ≈ 4/15, that is the roughly rounded value ... 24° =: εr for ε. In MS 1.12 ... ε becomes 23° 51' 20" =: εm ... The correct value of Ptolemy’s time is 23° 41' =: εc so that εm has an error of about 11'. (Marx PDF 5-6)

Let’s take εr = 24° for ε, as that is the rounded estimate Ptolemy gives in the Geography. Solving that horrendous equation—WolframAlpha—yields a latitude for Rhaiba of about 59° 36'. This is less than 9' south of the value given in Book 2. On the ground, this amounts to approximately 12-13 km.

| City | Geography | Longitudes | Latitudes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ῥαιβα | Book 2 | 12° 00 | 59° 45' |

| Ῥαιβα | Book 8 (Marx) | 12° 30' | 59° 36' |

| Ῥαιβα | Book 8 (Müller) | 11° 30' | 59° 36' |

| Ῥαιβα | Book 8 (Müller emended) | 12° 00' | 59° 36' |

Identity

Ptolemy’s Rhaiba has been identified over the centuries with about half a dozen candidate sites. Writing of County Laois, or Queen’s County, in 1607, the English antiquarian William Camden remarked:

Where also the Barrow, rising out of Slew-Blomey hills on the west, after a solitary course through the Woods, sees the old City Rheba, a name which it still preserves entire in its present one Rheban; though instead of a City, it is now but the shadow of a City, consisting of some few Cottages and a Fort. (Camden 1356-1357)

Camden is referring to Castle Rheban, which sits on the west bank of the Barrow about 5 km upstream from Athy. Although the site now comprises the ruins of an Anglo-Norman castle built by Richard de Saint Michael in the late 12th century, a much older rath, or ringfort, known as the Moat of Rheban, is associated with it, lying about 1 km to the south. In 1892, Walter Fitzgerald described this Moat thus:

The Moat of Rheban stands about half an English mile [1 km] to the south of Castle Rheban. This earthwork is of great antiquity. It consists of an artificial moat or mound 38 feet [12 m] in height, attached to the north-east side of which is a triangular enclosure, surrounded by a deep, broad dyke, which gives the place the appearance of a rath. This enclosure is said to have an entrance on the north side, closed by an iron door, leading into a cave or underground chamber. The moat itself for many years past has been used as a gravel-pit, and already about two-thirds of it have been carted away. Some seventy-five years ago McEvoy’s cottage, between it and the road, was at the edge of the moat, but now a potato-garden is laid out on the excavated portion. In the next field to the moat there was, some twenty years ago, a small moat, which was levelled by a Mr. Joseph Butler, who then lived at Castle Rheban. Under the mound was discovered a kistvaen, or dry-walled chamber, full of human bones. This field is called “the Bridge Field.” One corner of it, near the moat, is never tilled, as many human bones lie close to the surface; in consequence, it is known as “the Churchyard.” (Fitzgerald 168)

Fitzgerald surmises that Castle Rheban was built for the defence of the nearby ford—in Irish, Athy is Áth Í, meaning The Ford of Ae—taking the place of the rath mentioned above, which must have been erected for the defence of the same ford in ancient times (Fitzgerald 170).

According to Darcy & Flynn, Camden was referring to the Great Moat of Ardscull at Kilmead in County Kildare, which lies about 6 km northeast of Athy. This is actually the remains of a motte-and-bailey constructed in the late 12th or early 13th century by the Anglo-Normans, so it can hardly be Ptolemy’s noteworthy city. It does not even lie on the Barrow, let alone on its west bank. I can only surmise that Darcy & Flynn confused the Great Moat of Ardscull with the similarly named Moat of Rheban associated with Castle Rheban.

The Moat of Rheban has survived to the present day, though its western section has been built over. There is also a townland called Moatstown in the vicinity, but the Moat lies in the neighbouring townland of Castlereban South.

Goddard Orpen rejected this popular identification:

We have now mentioned all the names on Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland itself, with the exception of the town of Ῥαιβα, an inland town perhaps intended to be included in the territory of Αὐτεινοι [Autenoi]. From the position assigned to it we might guess it to be near Lough Ree (Rib), perhaps on the important site of Athlone. It cannot have been Rheban in Co. Kildare, a name which perhaps is not older than the Caislen riabhan, or greyish castle, built by Robert de St. Michael in King John’s time. (Orpen 127)

Against this it could be claimed that Robert’s castle took its name from the nearby, and much older, rath. We don’t know what the original name of this structure was, but it does not make sense that a French-speaking Norman would give his castle an Irish name unless that name was a local native toponym.

In the annotations to Owen Connellan’s translation of the Annals of the Four Masters, we read:

Raiba ... is said by some antiquaries to have derived its name from Riogh-ban, signifying the habitation or fortress of the kings. (Connellan 313)

William Baxter and Samuel Lewis also give this etymology (Baxter 199, Lewis 91), which derives from the Old Irish combining form ríg- [royal-] and the noun badún [bawn].

Like Orpen, T F O’Rahilly thought that the name could be related to that of Lough Ree:

Raiba or Reba. Its location suggests a possible connexion with the name of Lough Ree, Loch Ríb (otherwise Loch Rí). Ríb, the legend goes, was ‘drowned’ in Loch Ríb, whence we may infer that (like the Eochu of Loch nEchach [Lough Neagh]) he was ultimately the god of the Otherworld believed to exist beneath the lake. Ríb would go back to *Rībos, which may possibly represent an earlier *Rēbos; and Ptolemy’s Raiba or Reba may possibly be intended for *Rēba. But all this, of course, is mere conjecture. (O’Rahilly 14)

Annie M Heiermeier, perhaps with a nod towards Orpen’s greyish castle, took issue with O’Rahilly’s speculations, but without offering an alternative candidate:

p. 14: Could not Ptol. Raiba/Rēba be associated with the Ir. adj. riabhach<rēbāko* ‘grey’? In the same way as we have a shorter argat/argit for Ir. Airgthech<argitāko*—‘silver-like’, we may perhaps take Ir. riabhach to be derived from a presupposed shorter raiba/rēba “grey”. The semasiological (and topographical) side of this explanation is satisfactorily given by hundreds of still living Irish names of places, towns, and townlands, which mean nothing else but “grey spot, greyish land or surface.” (Heiermeer 40)

Close to Lough Ree is the traditional midpoint of Ireland, the Hill of Uisneach, an area steeped in the history of ancient Ireland. Ptolemy’s coordinates do place Rhaiba close to the centre of the island.

Rathcroghan and Carnfree

The etymologists an Roman Era Names have provided an alternative and intriguing etymology of this name:

Ραιβα (or Ρεβα) πολις (Raiba 2,2,10) is the feminine or plural of Greek ραιβος ‘crooked, bent’, which is a meaning often attributed to place names, but does not help to identify this site. It was identified with Castle Rheban, south west of Dublin, by Camden around 1600, but somewhere nearer the centre of Ireland, such as Rathcrogan (the Ráth of Cruachan, the ancient capital of Connacht) and/or Carnfree seems more likely. (Roman Era Names)

As the royal seat of the ancient kings of Connacht, Rathcroghan was of ancient standing and great importance. It is precisely the sort of place one would expect to find listed among Ptolemy’s inland “cities”. However, it may be a better fit for another of his cities, the Other Regia, as we shall see in a future article. Carnfree is a megalithic site closely associated with Rathcroghan. It lies a mere 5 km to the south-southeast and is generally considered part of the Rathcroghan complex. Darcy & Flynn, however, favour this identification.

Rathcroghan and Carnfree are indeed somewhat nearer the centre of Ireland than Castle Rheban, but the Hill of Uisneach is even nearer. It is curious that T F O’Rahilly claimed that the Hill of Uisneach acquired its name because it lay at the vertex where the original provinces (or kingdoms) of Ireland met:

The Hill of Uisnech, between Mullingar and Athlone, was reputed to mark the centre of Ireland. A big natural rock on its side [the Catstone] was supposed to be the meeting-point of the provinces of Ireland. As the centre of the country Uisnech must have been a hallowed spot in early days ... Traditions have survived in Irish literature of a great assembly ... held there periodically on May-day ... The name Uisnech, which is unique in Irish topography, was probably given to it on account of its quadrilateral aspect as being the centre of the country. I take it to stand for *Ostināko-, ‘the angular place’, connected with Ir. uisin, ‘the temples [of the head]’, Sc. oisinn, ‘angle’. (O’Rahilly 171)

Is it possible that Ῥαιβα [crooked, bent] is Ptolemy’s (or one of his sources’) Greek translation of this native Celtic name?

In my opinion, the Hill of Uisneach is perhaps the best fit for Ptolemy’s Rhaiba. Its position is central, its important role in ancient Ireland is indisputable, and it is just possible that Ῥαιβα, meaning crooked or bent, is a Greek translation of the Celtic *Ostināko-, meaning angular. Uisneach is a popular candidate for Rhaiba, as a quick search on the Internet will prove, though I have not been able to discover who first proposed it.

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Owen Connellan (translator), The Annals of the Four Masters: Translated from the Original Irish of the Four Masters by Owen Connellan, with Annotations by Philip Mac Dermott and the Translator, Bryan Geraghty, Dublin (1846)

- Otto Cuntz, Die Geographie des Ptolemaeus: Gallia, Germania, Raetia, Noricum, Pannoniae, Illyricum, Italia, Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, Berlin (1923)

- Robert Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

- Walter Fitzgerald, Castle Rheban, Journal of the Co. Kildare Archaeological Society and Surrounding Districts, Volume 2 (1896-99), pp 167-178, County Kildare Archaeological Society, Edward Ponsonby, Dublin (1899)

- Annie M Heiermeier, “The British and Goidelic Element in Ireland”: Notes and Suggestions on T. F. O’Rahilly’s: Early Irish History and Mythology, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 82, Number 1 , pp 37-44, Dublin, (1952)

- Samuel Lewis, A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, Volume 1, S Lewis & Co, London (1840)

- Christian Marx, Investigations of the Coordinates in Ptolemy’s Geographike Hyphegesis Book 8, Archive for History of Exact Sciences, Number 66 (July 2012), pp 531-555, Springer Verlag, Berlin (2012)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Herbert Weir Smyth, A Greek Grammar for Colleges, American Book Company, New York (1920)

- Alfred Stückelberger & Florian Mittenhuber (editors) , Klaudios Ptolemaios Handbuch der Geographie: Ergänzungsband mit einer Edition des Kanons bedeutender Städte, Schwabe Verlag, Basel (2009)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- Moat of Rheban: Imagery © 2019 DigitalGlobe, map Data © 2019 Google, Fair Use

- The Catstone on the Hill of Uisneach: © Hodson Bay Hotel, Fair Use

- Carnfree: © Jim Knowles, Fair Use

- The Autumnal Equinox at the Hill of Uisneach: © Declan Murray @ Skyfab via Rollingnews.ie.

Salute history. Your post is awsome bro... loveed it.

Hello friend, happy new year, excellent writing, I love how good you are back, greetings and success

Excellent writing dear friend. Good luck.