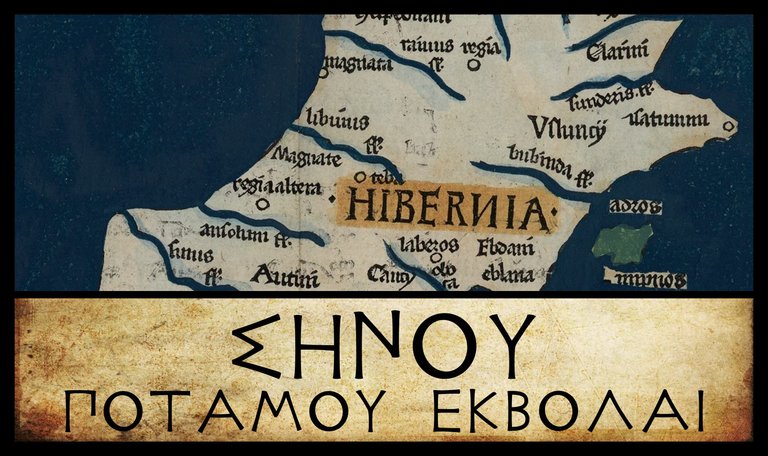

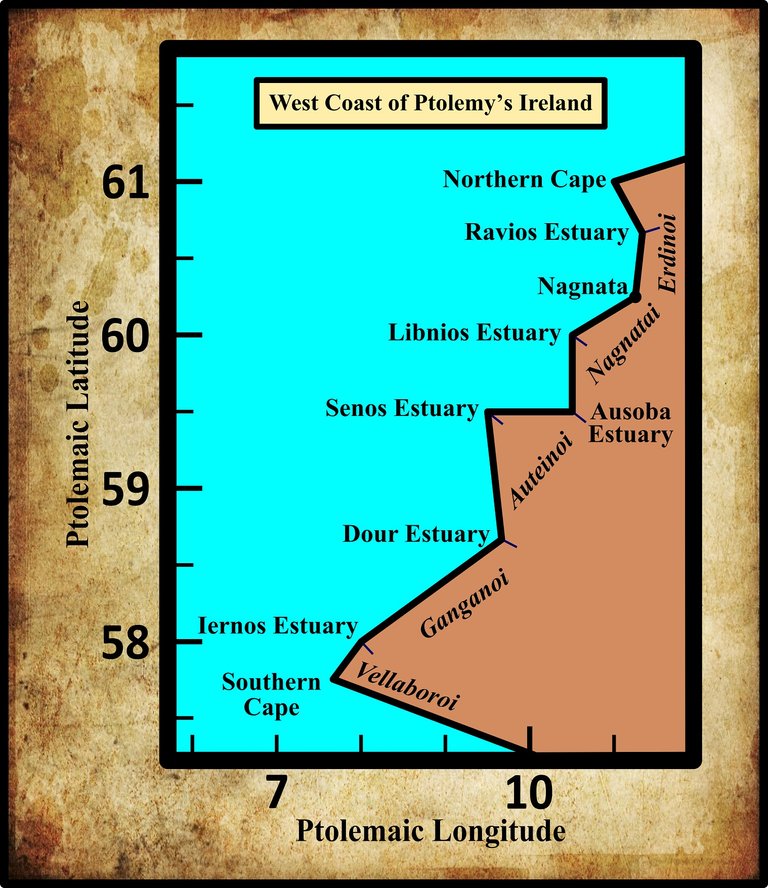

As we continue our voyage down the west coast of Ireland, with Claudius Ptolemy’s Geography as our sailing directions, our next landfall is by the mouth of the River Sēnos. This is one of the few toponyms in Ptolemy’s catalogue that can be confidently identified today: the Shannon is the longest river in these islands and it would have been inexplicable if Ptolemy had not included it in his description of Ireland. As the country’s longest and best known river, it is also the one that is most likely to have retained its ancient name.

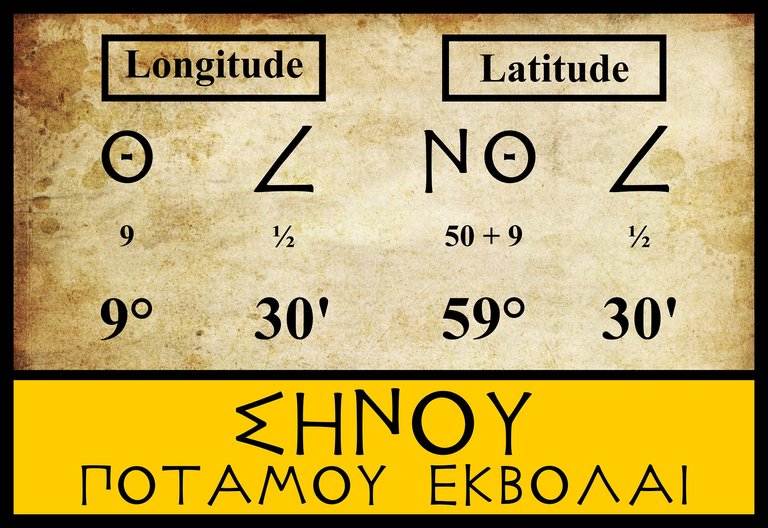

The three modern editors I am following place this feature in the same latitude as the mouth of the River Ausoba, 59° 30', but one degree to the west. Karl Müller does not give any variant coordinates for this feature or even comment on the latitude, but according to William Beauford:

Σηνου ποτ. ἐκβολαί, latitude 9° 30' in most copies, but there seems to be an error in the table, the latitude ought certainly to be 59° 30'. (Beauford 57)

The only error, however, is Beauford’s: he has read the longitude, which is correctly given as 9° 30', and mistaken it for the latitude. I examined three manuscripts online and they all give 9° 30' as the longitude and 59° 30' as the latitude:

Grec 1410, a 15th-century manuscript of Ptolemy’s Geography now housed in the Biblothèque Nationale de France in Paris. The Sēnos is the very first entry on the left-hand page.

Grec 1403, another 15th-century manuscript in Paris. the Sēnos is recorded on the seventh line of the right-hand page.

Vaticanus Graecus 191, one of the oldest surviving manuscript copies of Ptolemy’s Geography, now in the Vatican Library. The Sēnos is on folium 138v. It is the penultimate item in columns 5-7 at the bottom of the page.

Nevertheless, the position of Ptolemy’s river Sēnos has led to some head-scratching over the centuries, as it does not really fit the location of the Shannon estuary.

Ptolemy recorded this feature as Σηνου ποταμου εκβολαι [Sēnou potamou ekbolai], or mouth of the river Sēnos. Karl Müller noted only a single variant reading, Σίνου [Sinou]:

| Edition or Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| Müller, Wilberg, Nobbe | Σήνου | Sēnou |

| H or Π?, M, X | Σίνου | Sinou |

H is a pair of 15th-century manuscripts among the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1407 and Grec 1411 respectively. These manuscripts contain copies of an epitome of Ptolemy’s Geography. Browsing through them, I was unable to locate Ptolemy’s description of Ireland. Müller’s text is difficult to read (I have only been able to find a single copy of it online) and it is possible that the siglum I read as H is actually Π.

Π This manuscript of Ptolemy’s Geography was formerly in the Library of St Gregory on the Caelian Hill in Rome. In 1872 the government of the recently established Kingdom of Italy confiscated the contents of the library, which were subsequently dispersed. Many of the volumes were expropriated by the Vittorio Emanuele II National Library of Rome.

M is the Editio Argentinensis, which we have met several times before. It was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513.

X is Vaticanus Graecus 191, which dates from about 1296. It is believed that this manuscript preserves a very ancient tradition. Ptolemy’s description of Ireland is on folia 138v–139r. Curiously, Müller does not include this among the manuscripts with a variant reading, but it clearly does have σίνου. Perhaps Müller’s H (or what I read as H) is a typo for X, the letter Müller used for Vat Gr 191.

Identity

Over the centuries there has been almost unanimous agreement that Ptolemy’s River Sēnos is the Shannon, the longest river in Ireland. Only two authorities have dissented from this opinion: Goddard Orpen in the late 19th century, and Robert Darcy & William Flynn in the early 20th century.

In the early 17th century, the British antiquarian William Camden wrote:

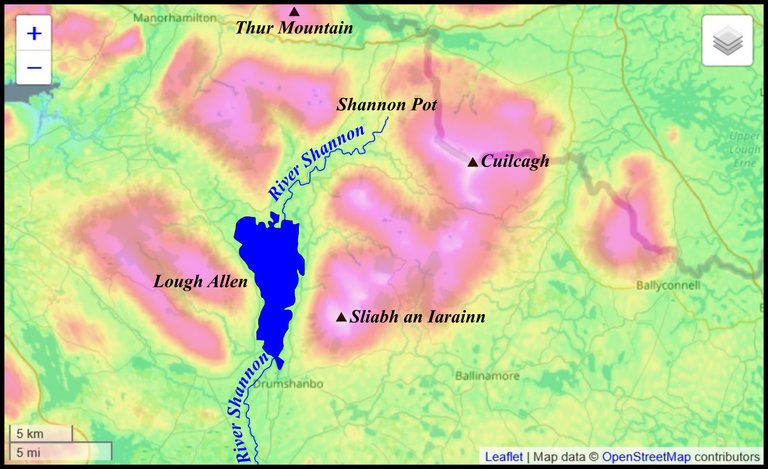

One side of this County [of Longford] is water’d by the Shanon, the noblest river in all Ireland; which (as we observed) runs between Meth and Connaught. Ptolemy calls it Senus, Orosius Sena, and in some Copies Sacana; and Giraldus, Flumen Senense. The Inhabitants thereabouts call it the Shannon, that is (as some explain it) the ancient river. It rises in the County of Trim, out of the mountains of Therne. (Camden 1373-1374)

This short passage is full of inaccuracies. The Shannon rises in County Cavan, near the slopes of Cuilcagh Mountain. There is no County Trim, and there never has been. Apparently, Camden wrote Letrim and his 18th-century editor Edmund Gibson mistranscribed it. The Mountains of Therne are probably to be identified with the Thorne Mountains, which appear on several 16th- and 17th-century maps of Ireland. In the northwest of County Leitrim is a mountain still known today as Thur Mountain. It sits about 11 km northwest of the Shannon Pot, where the river actually rises.

Paulus Orosius was an Iberian historian, who studied under St Augustine of Hippo. His Seven Books of History Against the Pagans includes a geographical overview of the world as it was known in the early 5th century. His very brief description of Ireland runs as follows:

Ireland, an island situated between Britain and Spain, is of greater length from south-west to north. Its nearer coasts, which border on the Cantabrian Ocean, look out over the broad expanse in a southwesterly direction toward far-off Brigantium, a city of Gallaecia, which lies opposite to it and which faces to the northwest. This city is most clearly visible from that promontory where the mouth of the Scena River is found and where the Velabri and the Luceni are settled. Ireland is quite close to Britain and is smaller in area. It is, however, richer on account of the favorable character of its climate and soil. It is inhabited by tribes of the Scotti. (Orosius 1:2)

Orosius’s spelling Scena reflects the contemporary Latin pronunciation of sce- as she-, as in the modern Italian word scena. This was noted almost a century ago by R A S Macalister:

Incidentally Orosius gave trouble to Irish topographers, ancient and modern, by speaking of an Irish river Scena, setting them on a hunt for a non-existent Inber Scēne. As sc conventionally represents the sound of sh (compare the Vulgate Judges, xii, 6, where the Hebrew word shibbōleth is rendered scibboleth), we must pronounce this word as Shena, and it is then easily recognised as Orosius’ version of Sinann (genitive Sinna) or “Shannon.” (Macalister xxxi)

Recently, the Irish historian Donnchadh Ó Corráin has suggested that Orosius was born in Britain and spent some time Ireland as a slave, before escaping to the Continent. His short paper on the subject includes a detailed analysis of the passage quoted above and is well worth reading.

In his Topographia Hibernica (The Topography of Ireland), Gerald of Wales—Giraldus Cambrensis—actually referred to the Shannon as Sinnenus, which is clearly a Latinized version of the same Old Irish name Sinann. Unlike Orosius, who lived eight centuries before him, Gerald did not attempt to preserve the sh- sound of the Irish. Perhaps Orosius did live in Ireland for a while and was familiar with the native pronunciation.

The etymology William Camden transmitted has been endorsed in the modern era by the Celticist T F O’Rahilly:

Sēnos. As the Shannon is evidently intended, we should read Senos, or (fem.) Senā, ‘the ancient (goddess)’. Compare Orosius’s Scenae fluminis ostium, which probably means ‘the mouth of the Shannon’ (read Senae for Scenae). The Old Irish name Sinann would go back to Senunā, which occurs, presumably as a woman’s name, in an inscription found in Kent ... The O. Ir. genitive Sinnae (E. Mod. Ir. Sionna), instead of the *Sinne (< *Senuniās) we should expect, owes its non-palatal -nn- to the influence of the non-palatal -n- of the other cases. (O’Rahilly 4-5)

The etymologists at Roman Era Names have suggested an alternative origin for the name:

Σηνου (Σινου) river mouth (Senu or Sinu 2,2,4) is usually identified with the modern river Shannon. This name probably came from PIE *sai-/sei- ‘to bind’, the root of English sinew and Irish sin ‘collar’, referring to the long and sinuous estuary leading up to Limerick. This analysis rejects the common idea that the name meant ‘old’, from PIE *sen-, and also a possible link with PIE *senə- ‘apart’.

No reason is given for rejecting what seemed to be a perfectly good etymology, though it has to be conceded that the Shannon estuary is sinuous. They seem to have been swayed by Ptolemy’s use of the long vowel eta, η, rather than the short epsilon, ε. But if this name refers to the Shannon, whose name in Old Irish is Sinann, then O’Rahilly was right to emend Ptolemy’s Σηνου [Sēnou] to Σενου [Senou]. According to Rudolf Thurneysen, the short i of Old Irish derives from the short vowels i and ĕ of Indo-European. The Proto-Indo-European sei- would have given something like Sénann in Old Irish. Thurneysen does, however, concede that in exceptional circumstances IE ei may have become O Ir i:

78. ... So too ei or (after the loss of i) e in hiatus seems to have become i. (Thurneysen 49)

In linguistics, hiatus refers to the pronunciation of two successive vowel as separate syllables rather than as a monosyllabic diphthong. I do not think that applies to this case.

| Old Irish | Indo-European or Celtic | §§ |

|---|---|---|

| i | i, ĕ, ei | 57, 75-79 |

| é | ei, ĕ, ă | 53-56 |

Source: Rudolf Thurneysen, A Grammar of Old Irish

O’Rahilly noted other occasions where a short e in a Celtic name was represented in Greek by the long η:

Compare η for ε in Ptolemy’s Δημηται, for Dĕmĕtai ([Welsh] Dyfed), and in Polybius’ Σηνωνες for Sĕnŏnĕs. In a Celtic inscription at Avignon we find short e written η in Βηλησαμι and νεμητον (Rhys, Celtic Inscrr. of France and Italy 13 f.) (O’Rahilly 4 fn 4)

On balance, I do not think there is sufficient reason to throw out a long-standing and perfectly plausible etymology in favour of one that is doubtful.

The 17th-century Irish antiquarian James Ware also identified Ptolemy’s River Sēnos with the Shannon:

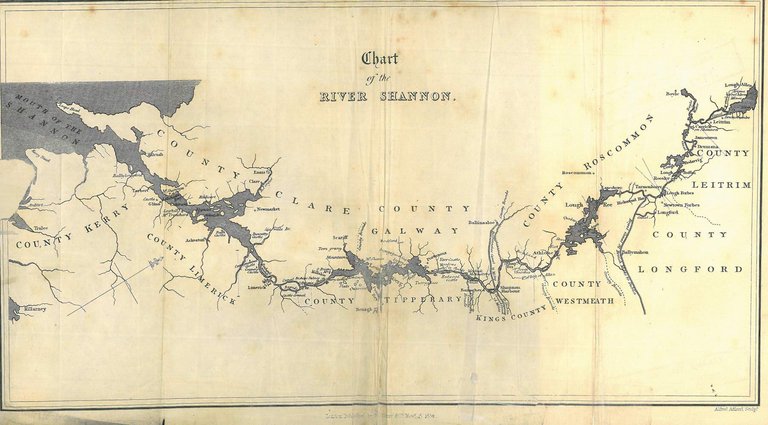

Senus, a River. The River Shanon, by Orosius called Sena, the most noble River of all Ireland. It has its Course in a plentiful _Stream from Slieunerin (a Mountain so called from the Veins of Iron with which it abounds) in the County of Leitrim. (Ware & Harris 43-44)

Like Camden, Ware misspells Orosius’s Scena and places the source of the Shannon in County Leitrim instead of County Cavan. His Slieunerin or Iron Mountain (Irish: Sliabh an Iarainn) refers to the highest peak in the Iron Mountains, the southern spur of the Breifne Mountains, which straddle the two counties and also extend into the neighbouring County Fermanagh. Slieve Anierin, as the Irish name has been Anglicized, sits to the east of Lough Allen, about 16 km south of the actual source of the Shannon.

Ware’s 18th-century editor Walter Harris, a respected antiquarian in his own right, added the following comment to Ware’s entry:

Etymologists have been busy with the Explanation of the Word Shanon, and differ widely in their Accounts. Some make it to signify Shan-awn, or Shan-Avon, i. e. the antient River; some Senn-Aun or Synn-Avon, two British Words signifying the Slow or Stagnating River, from its slow Course, and the many Loughs it stagnates into in its long passage from the Source to its Mouth. But the most singular Notion of all is, that it does not bear the Name of the Shanon till its Union with the Inny, being before called only the Shann, and that from thence it incorporates with it a Part of the Name, as well as its Waters, and is called Shann-Inny, or Shannin. But I fear it will be judged that I give two great a Countenance to Trifles by only mentioning them. (Ware & Harris 44)

Whenever Harris mentions British words, one suspects he has been consulting the Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum (Glossary of British Antiquities) of the Welsh Celticist William Baxter. And, sure enough, this is confirmed by Baxter’s entry for the Senus:

Senus A river of Ireland according to Ptolemy, called the Sena by Orosius, and today known as the Shannon; as though one might call it Senn aün or Synn avon, i. e. the Sluggish or the Slow River. One could also call it Sluggish because it stagnates and lingers in numerous lakes. There is also another Senus near Brussels in Belgium, called the Arsena in the Ravenna Cosmography, with the Brittonic definite article [= ir]. (Baxter 215)

Charles Trice Martin lists the River Shannon under both the masculine and feminine forms: Senus and Sena. The modern name, in Irish, is Sionna, which is feminine, as are almost all river names in modern Ireland, as noted by O’Rahilly:

In Irish literature and speech river-names are, almost without exception, feminine; and this is also the Welsh usage. Ptolemy’s names apparently come down from an early period, when a river-name might be of either gender. (O’Rahilly 3)

At some point in our history, the name of the Shannon was feminized from Senos to Sena, eventually giving rise to the modern Sionna.

After more than three centuries of unanimity, Goddard Orpen bucked the trend when he suggested that Ptolemy’s River Sēnos might not after all refer to the Shannon. After quoting the passage about the geography of Ireland in Orosius, he commented:

From this passage, which seems to have reference to the S.W. extremity of Ireland, thus agreeing with the position clearly assigned by Ptolemy to the Οὐελλάβοροι [Vellaboroi], I feel inclined to identify the ostium fluminis Scenæ (or in the parallel passage of the Pseudo-Æthicus, Sacancæ), not with the Shannon, as is usually done, but with the inbher Scéne of the bardic literature, i.e. with the great estuary now known as the Kenmare River. (Orpen 119)

We have already heard Macalister refute the idea that Inbher Scéne was anything other than the Shannon estuary, so I will not comment further. The Pseudo-Æthicus refers to the Cosmographia of Æthicus of Ister, a work purporting to be a Latin translation from the Greek of the travels of a Greco-Scythian voyager called Æthicus. The work is generally considered to be a 7th- or 8th-century work of fiction. Its brief description of Ireland was obviously lifted from Orosius.

Curiously, on the previous page of his article, Orpen seemed to endorse the consensus view:

The river Σηνος [Sēnos] is generally taken to he the Shannon (Sionainn, or, according to an earlier form, Sinand, genitive Sinda) from the similarity of the name, though the Δούρ [Dour] is nearer the proper position for that river. If the Σηνος be the Shannon, then the Δούρ and the ’Ιερνος would represent two of the estuaries in Kerry and Cork. (Orpen 118)

Karl Müller, whose edition of Ptolemy’s Geography was published in 1883, took this opportunity to get several things off his chest:

Cf the Senua mentioned among the rivers of Britain in the Ravenna Cosmography 5:31 (2nd Edition by Parthey, p 439). Vaticanus 191 has a river Σῆνον [Sēnon] in European Sarmatia (Geography 3:5:1), where other manuscripts read Χρόνον [Khronon]. An Irish river is recorded in Pseudo-Æthicus (p 730 in the Greek edition) and in Orosius (Book 1, p 27): _Whose [i.e. Ireland’s] nearer coasts, which border on the Cantabrian Ocean, look in a southwesterly direction toward Brigantium, a city of Gallaecia, which lies opposite to them and which faces to the west-northwest ... from that precipitous promontory where the mouth of the River Sacana [Scena in Orosius] is found and where the Velabri and the Luceni are settled. _ Compare this with what we read in the anonymous Ravenna Cosmography 5:32 (Parthey p 440) concerning the rivers of Ireland or [as it is called] Scotia: Many rivers cross this land of Scotia, among which may be named the Sodisinam, the Cled and the Terdec. I do not know whether these names are to be emended thus: Atsobi (Ptolemy’s Ausoba), Sina (Ptolemy’s Senus, the modern Shannon), Moled (Malig, which has its mouth next to that of the Shannon), Terdec (either Ptolemy’s Dur or a river near the town of Tarbek which falls into Turloughmore Lake and from there enters Lough Corrib above Galway City). Both the similarity of the name and the distance between it and the Southern Promontory strongly suggest that Ptolemy’s Senum is the modern Shannon, the longest river in Ireland.

I will leave the reader to consult Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews’ Britannia in the Ravenna Cosmography: A Reassessment for the latest opinion on those three “Irish” rivers in this work: long story short, they are not Irish rivers at all, but Scottish rivers, the Cled being the Clyde.

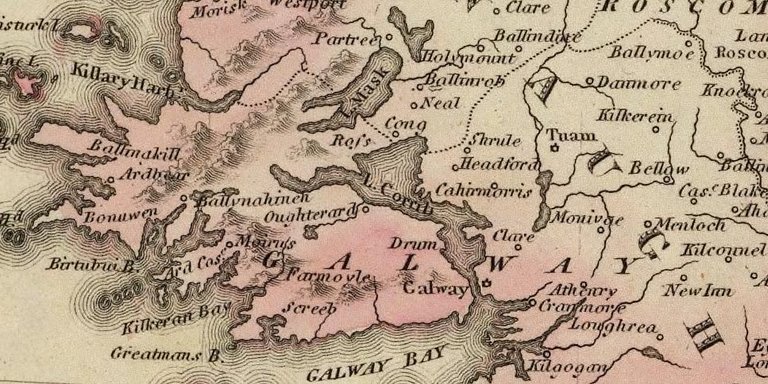

I have no idea where Tarbek is. I have never heard of such a place, but John Speed’s map of 1611-12 has a Fartbeg on the Mayo side of the Black River, which flows into Lough Corrib. There is a townland here called Gortbrack, which could possibly have been corrupted to Fartbeg, and then Tarbek. The river Müller is talking about would then be the Black River, though the nearby River Clare used to flow through Ireland’s largest turlough (a seasonal lake that dries up in the summer). Turloughmore is no more, but some old maps show a large lake to the east of Lough Corrib:

Following this passage, Müller suggests that if Ptolemy’s Sēnos is the Shannon, then the four landmarks that lie between the Shannon and the Northern Promontory about 1200 (~200 km) stadia away—the River Ausoba, the River Libnios, Nagnata City and the River Ravios—could represent five days’ sailing. Goddard Orpen repeated this opinion a few years later:

The four points given between the Shannon and the northern promontory may probably be regarded as dividing the distance into five days’ sail. (Orpen 118)

This unsubstantiated idea led Müller to identify these landmarks as follows:

| Ptolemy | Müller |

|---|---|

| Ravios | River Eske at Donegal Town |

| Nagnata | Ballina on the River Moy |

| Libnius | Killary Harbour near Clifden |

| Ausoba | Corrib River at Galway City |

The rest of this passage need not detain us, as it is concerned with the Ravenna Cosmography and not Ptolemy.

Given the widespread consensus going back four hundred years that Ptolemy’s Sēnos is the Shannon, one might have been forgiven for thinking that the debate was closed. Recently, however, Robert Darcy and William Flynn have been bold enough to reopen it:

As with some scholars, we had trouble placing the Senus. Locations from the mouth of the Shannon to Limerick yielded errors exceeding 100 kilometres. Our data indicated that a better fit will be found to the north and west. The centre of the entrance to Galway Bay makes the best fit. (Darcy & Flynn 66)

They actually identified Ptolemy’s Sēnos not with a river mouth, but with the North Passage, the entrance to Galway Bay to the northwest of Inishmore, the largest of the Aran Islands.

This seems perverse, but Darcy and Flynn were relying on a mathematical algorithm to “correct” Ptolemy’s coordinates. In their defence, Ptolemy’s placement of the mouth of the Sēnos is difficult to reconcile with the actual geography on the ground.

In my opinion, correcting Ptolemy’s figures while ignoring his linguistic evidence is not the best course to take—especially when it leads us to throw out one of our most secure identifications.

| Shannon | KenmareRiver | Galway Bay |

|---|---|---|

| Camden (1607) | - | - |

| Ware (1654) | - | - |

| Baxter (1733) | - | - |

| O’Conor (1766) | - | - |

| Martin (1892) | - | - |

| - | Orpen (1894) | - |

| O’Rahilly (1946) | - | - |

| Mac an Bhaird (1991-93) | - | - |

| Francis (1994) | - | - |

| Ikins (1996-2005) | - | - |

| Bursche & Warner (2000) | - | - |

| Duffy (2000) | - | - |

| Stempel (2002) | - | - |

| Toner (2002) | - | - |

| Keenan (2003) | - | - |

| - | - | Darcy & Flynn (2008) |

Source: Darcy & Flynn 56

The Sēnos is one of the few items on Ptolemy’s list of Irish toponyms whose identity is known today with absolute certainty: it can only be the River Shannon. It may be difficult to reconcile the geographical position of the Shannon estuary with the location Ptolemy assigns to this feature, but that speaks to the inaccuracy of Ptolemy’s coordinates, not his names. And that is a subject for another day.

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Otto Cuntz, Die Geographie des Ptolemaeus: Galliae, Germania, Raetia, Noricum, Pannoniae, Illyricum, Italia, Weidmann, Berlin (1923)

- Robert Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

- Seán Duffy, Atlas of Irish History, Second Edition, Gill & MacMillan, Dublin (2000)

- Keith J Fitzpatrick-Matthews, Britannia in the Ravenna Cosmography: A Reassessment, Academia (2013)

- Louis Francis (editor, translator), Geographia: Selections, English, University of Oxford Text Archive (1995)

- Gerald of Wales, Thomas Forester (translator), Richard Colt Hoare (translator), Thomas Wright (editor), The Historical Works of Giraldus Cambrensis, George Bell & Sons, London (1905)

- Giraldus Cambrensis, Topographia Hibernica, Edited by James F Dimock, Longmans, Green, Reader & Dyer, London (1867)

- R A Stewart Macalister (editor & translator), Lebor Gabála Érenn: The Book of the Taking of Ireland, Part 1, The Educational Company of Ireland, Ltd, Dublin (1938)

- Charles Trice Martin, The Record Interpreter: A Collection of Abbreviations, Latin Words and Names Used in English Historical Manuscripts and Records, Reeves and Turner, London (1892)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Charles O’Conor, Dissertations on the History of Ireland, G Faulkner, Dublin (1766)

- Donnchadh Ó Corráin, Orosius, Ireland, and Christianity, Peritia, Volume 28, pp 113-134, BREPOLS Publishers (2017)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Paulus Orosius, Seven Books of History Against the Pagans, R P Pryne, Toronto (2015)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Pseudo-Æthicus, The Cosmography of Aethicus Ister, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Département des Manuscrits, Latin 9661

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- John Rhys, The Celtic inscriptions of France and Italy, Proceedings of the British Academy, Volume 2, pp 273-373, Oxford University Press, London (1906)

- Patrizia de Bernardo Stempel, Ptolemy’s Celtic Italy and Ireland: A Linguistic Analysis, in David N Parsons & Patrick P Sims-Williams (editors) Ptolemy: Towards a Linguistic Atlas of the Earliest Celtic Placenames of Europe, University of Wales, CMCS Publications, Aberystwyth (2000)

- Rudolf Thurneysen, Osborn Bergin (translator), D A Binchy (translator), A Grammar of Old Irish, Translated from Handbuch des Altirischen (1909), Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1998)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- The Course of the Shannon: Henry D Inglis, Journey Throughout Ireland, Whittaker & Co, London (1835), Public Domain

- The Source of the River Shannon: © OpenStreetMap, Open Data Commons Open Database License

- The Shannon and Lough Allen: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- River Shannon at Killaloe, County Clare: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- John Senex’s New Map of Ireland (1720): Public Domain

- Galway (John Speed, 1611-1612): © Cambridge University Library, Fair Use

- Galway (Lucas Fielding Jr, 1823): David Rumsey Map Collection, Creative Commons License

- Inishmore (The North Passage Is on the Far Side of the Island): © Tourism Ireland, Fair Use

- The River Shannon at Limerick (Between Sarsfield Bridge and Thomond Bridge): Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

Very good post .

StAy support us

Excellent post dear buddy

There’s certainly a reason why these cliffs are Ireland’s most-visited natural attraction. The stunning, jagged coastline is best seen with moody skies that offset the emerald waters below.

Excellent post good article very nice history I like your post thanks for sharing with us dear @harlotscurse

Excellent story friend very good work is fantastic this post thanks for sharing with us